A Case Study of the Social Responsibility Paradigm in Colorado Museums

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time Travelers

Sioux City Museum & Historical Association Members Your membership card is your passport to great Benefits Key: benefits at any participating Time Travelers C = Complimentary or discounted museum publication, gift or service museum or historic site across the country! D = Discounted admission P = Free parking F = Free admission R = Restaurant discount or offer Please note: Participating institutions are constantly G = Gift shop discount or offer S = Discounted special events O = Does not normally charge admission T = Free or discounted tour changing so calling ahead to confirm the discount is highly recommended. CANADA The Walt Disney Family Museum Georgia Indiana TIFF • (888)599-8433 San Francisco, CA • (415)345-6800 • Benefits: F American Baptist Historical Soc. • (678)547-6680 Barker Mansion Civic Center • (219) 873-1520 Toronto, ON • Benefits: C • tiff.net waltdisney.org Atlanta, GA • Benefits: C • abhsarchives.org Michigan, IN • Benefits: F T • barkermansion.com Twentynine Palms Historical Society Atlanta History Center • (404)814-4100 Brown County History Center USA Twentynine Palms • (760)367-2366 • Benefits: G Atlanta, GA • Benefits: F • atlantahistorycenter.com Nashville, IN • (812)988-2899 • Benefits: D G Alabama 29palmshistorical.com Augusta Museum of History • (706)722-8454 browncountyhistorycenter.org Berman Museum of World History USS Hornet Museum • (510)521-8448 Augusta, GA • Benefits: F G • augustamuseum.org Carnegie Center for Art & History Anniston, AL • (256)237-6261 • Benefits: D Alameda, CA • Benefits: D • uss-hornet.org -

2017 Preliminary Conference Program Photo: VISIT DENVER Western Altitude / Western Attitude

Photo: VISIT DENVER MPMA Regional Museum Conference 64th Annual MPMA Conference October 15 - October 19 | Denver, CO Photo: ToddPowell Photo Credit VISITDENVER 2017 Preliminary Conference Program Photo: VISIT DENVER Western Altitude / Western Attitude Photo: VISIT DENVER Photo: VISIT DENVER/Steve Crecelius Western Altitude / Western Attitude Join in the conversation: #MPMA2017 Why Museums Are Needed Now More Than Ever Photo: VISIT DENVER/Steve Crecelius Invitation from the MPMA Conference Chairs Dear Colleagues and Friends: Join us this fall in Denver, Colorado…where the Rocky Mountains meet the Great Plains. What an appropriate place for the 2017 annual meeting of the Mountain-Plains Museums Association (MPMA), an organization where the museums of the mountains and plains come together. And MPMA even had its origins in this area. Here you will discover Western Altitudes and Western Attitude at our museums, historic sites, and within our people. John Deutschendorf was so impressed by Denver that he took it as his last name, becoming one of Colorado’s beloved balladeers, singing about our altitudes and our attitudes. John Denver wasn’t alone in his attraction to the area; millions have been rushing to the state since gold was discovered in 1859. What you will discover during our conference is that Denver is not just a single city but an entire region offering many great cultural resources as well as great scenic beauty. Our evening events will capitalize on the best that the Denver area has to offer. The opening event will be hosted in the heart of Denver by History Colorado, site of exhibits about Colorado’s history (including “Backstory: Western American Art in Context,” an exciting collaboration with the Denver Art Museum), and by the Clyfford Still Museum, where the works and life of one of the fathers of abstract expressionism are exhibited. -

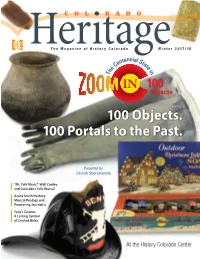

100 Objects. 100 Portals to the Past

The Magazine of History Colorado Winter 2017/18 100 Objects. 100 Portals to the Past. Presented by Colorado State University “Mr. Folk Music”: Walt Conley and Colorado’s Folk Revival Azalia Smith Hackley: Musical Prodigy and Pioneering Journalist Tony’s Conoco: A Lasting Symbol of Crested Butte At the History Colorado Center Steve Grinstead Managing Editor Micaela Cruce Editorial Assistance Darren Eurich, State of Colorado/IDS Graphic Designer The Magazine of History Colorado Winter 2017/18 Melissa VanOtterloo and Aaron Marcus Photographic Services How Did We Become Colorado? 4 Colorado Heritage (ISSN 0272-9377), published by The artifacts in Zoom In serve as portals to the past. History Colorado, contains articles of broad general By Julie Peterson and educational interest that link the present to the 8 Azalia Smith Hackley past. Heritage is distributed quarterly to History Colorado members, to libraries, and to institutions of A musical prodigy made her name as a journalist and activist. higher learning. Manuscripts must be documented when By Ann Sneesby-Koch submitted, and originals are retained in the Publications 16 “Mr. Folk Music” office. An Author’s Guide is available; contact the Walt Conley headlined the Colorado folk-music revival. Publications office. History Colorado disclaims By Rose Campbell responsibility for statements of fact or of opinion made by contributors. History Colorado also publishes 24 Tony’s Conoco Explore, a bimonthy publication of programs, events, A symbol of Crested Butte embodies memories and more. and exhibition listings. By Megan Eflin Postage paid at Denver, Colorado All History Colorado members receive Colorado Heritage as a benefit of membership. -

Colorado Women Take Center Stage

January/February 2020 Colorado Women Take Center Stage At the Center for Colorado Women’s History and Our Other Sites Interactives in What’s Your Story? help you find your superpower, like those of 101 influential Coloradans before you. Denver / History Colorado Center 1200 Broadway. 303/HISTORY, HistoryColoradoCenter.org ON VIEW NOW A Legacy of Healing: Jewish Leadership in Colorado’s Health Care Ballantine Gallery Sunlight, dry climate, high altitude, nutritious food, fresh air—that was the prescription for treating tuberculosis. As thousands flocked to Colorado for a cure, the Jewish community led the way in treatment. Co-curated by Dr. Jeanne Abrams from the University of Denver Libraries’ Beck Archives, A Legacy of Healing tells the story of the Jewish community’s involvement in revolutionizing our state’s health care in the late 19th and early 20th century. See rare film footage, medical tools and photographs from the top-tier Denver tuberculosis hospitals. Journey through the stories of Jewish leaders and ordinary citizens committed to caring for those in need. A Legacy of Healing honors the Jewish community for providing care to all Coloradans regardless of faith, race or social standing. NEW NEW & VIEW ON A Legacy of Healing is made possible through Rose Medical Center, the Chai (LIFE) Presenting Sponsor. The Education Sponsor is Rose Community Foundation. National Jewish Health, Mitzvah (Act of Kindness) Sponsor. ON VIEW NOW What’s Your Story? Owens Hickenlooper Leadership Gallery What’s your superpower? Is it curiosity—like the eleven-year-old who invented a way to test water for lead? Is it determination—like the first woman to work in the Eisenhower Tunnel? Generations have used their powers for good to create a state where values like innovation, collaboration and stewardship are celebrated. -

Colorado Stories: Interpreting History for Public Audiences at the History Colorado Center William Convery III

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-3-2012 Colorado Stories: Interpreting HIstory for Public Audiences at the History Colorado Center William Convery III Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Convery, William III. "Colorado Stories: Interpreting HIstory for Public Audiences at the History Colorado Center." (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/15 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i COLORADO STORIES: INTERPRETING COLORADO HISTORY FOR PUBLIC AUDIENCES AT THE HISTORY COLORADO CENTER BY William J. Convery III B.A., History, University of Colorado, Boulder, 1991 M.A., American Western History, University of Colorado, Denver, 1998 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2012 ii © 2012, William J. Convery III All Rights Reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The exhibits at the History Colorado Center reflect the work and dedication of an extensive team. Many, many people have contributed to the research, development, and writing of this exhibit over time. I want to thank History Colorado staffers Bridget Ambler, donnie betts, B. Erin Cole, Melissa de Bie, Barbara Dey, Jay Di Lorenzo, Deborah Espinosa, Sarah Gilmor, Shelia Goff, Steve Grinstead, Ben Fogelberg, Melanie Irvine, Abby Fisher Hoffman, April Legg, Becky Lintz, Moya Hansen, Beth Kaminsky, Rick Manzanares, Aaron Marcus, Lyle Miller, James Peterson, Elisa Phelps, J. -

July2017.Pdf

Benefits Key: C - Free or Discounted Gift, Publication, or Service D - Discounted Admission F - Free Admission G - Gift Shop Discount P - Free Parking R - Restaurant Discount S - Special Event Offer T - Free or Discounted Tour(s) It is highly recommended to call ahead and do your own independent research on any institution you plan to visit. Name City Benefit Alabama Berman Museum of World History Anniston D Alaska Arizona Arizona Historical Society - Arizona History Museum Tucson D Arizona Historical Society - Downtown History Museum Tuscon D Arizona Historical Society - Fort Lowell Museum Tuscon D Arizona Historical Society - Pioneer Museum Flagstaff D Arizona Historical Society - Sanguinetti House Museum Yuma D Arizona Historical Society Museum at Papago Park Tempe D Gila County Historical Museum Globe F, T, P Heritage Square Foundation Pheonix T Show Low Historical Museum Show Low F, G The Jewish History Museum Tucson F Arkansas Historic Arkansas Museum Little Rock F, P, G Old Independence Regional Museum Batesville F Rogers Historical Museum Rogers G, S Shiloh Museum of Ozark History Springdale G California Banning Museum Wilmington G Bonita Museum and Cultural Center Bonita F, G, P California Historical Society San Francisco F Catalina Island Museum Avalon F Dominguez Rancho Adobe Museum Rancho Dominguez F, G, S El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park Santa Barbara F Folsom History Museum Folsom F Friends of Rancho Los Cerritos Long Beach G, S Goleta Valley Historical Society Goleta F, G Heritage Square Museum Los Angeles -

Strategic Plan 2021 Table of Contents

Strategic Plan 2021 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................. 2 Strategic Planning Process.......................................................... 3 Committee Members.................................................................... 4 Mission Statement........................................................................ 7 Our Values..................................................................................... 8 One-Year Vision Statement and Goals......................................... 10 Five-Year Vision Statement and Goals......................................... 12 Ten-Year Vision Statement and Goals.......................................... 14 Re-Evaluation of Strategic Plan.................................................... 15 Introduction Strategic Planning Process We have ended our tenth year on an upbeat note, despite a late start due to the coronavirus In 2019, HistoriCorps’ Board of Directors and Executive Director looked towards HistoriCorps’ tenth epidemic. Our team rose to the occasion, securing financial assistance from the Federal CARES Act year, our bright future, and agreed that we were overdue for a strategic plan. For many fledgling and developing effective protocols to keep our field staff and volunteers safe.e W owe thanks to our non-profit organizations, growth occurs so quickly that collaborative, long-term planning is sidelined; friends at the Forest Service, other Federal land management agencies and NGO partners who stood day-to-day -

Annual Report 2016/2017 Mission

Annual Report 2016/2017 Mission History Colorado inspires generations to find wonder and meaning in our past and to engage in creating a better Colorado. Vision History Colorado leads through accessible, compelling programs in education, preservation, and stewardship; serves Coloradans and enriches communities statewide; connects collections, places, people, and their stories with audiences in meaningful ways; and pursues sustainability through smart planning and sound business practices, while diversifying its financial base. Our Goals The Stephen Hart Library & Research Center is the portal to History Colorado’s collections of historic photography, artifacts, books, documents, and other resources. To inspire a love of, connection to, and engagement in Colorado and the state’s history. To provide excellent stewardship of Colorado’s past through our collections. History Colorado Board of Directors, as of June 30, 2017 To build an efficient, effective, and financially robust organization Mr. Marco Antonio Abarca to ensure our sustainability into the future. Ms. Cathy Carpenter Dea Ms. Cathey McClain Finlon Mr. Robert E. Musgraves, Chair Mr. Rick A. Pederson On the cover: Ms. Ann Alexander Pritzlaff Top image: In a partnership with the three Ute Indian tribes of Colorado, Mr. Alan Salazar the expanded Ute Indian Museum in Montrose opened with all-new spaces, exhibitions, and programs. Mr. Christopher Tetzeli Ms. Tamra J. Ward, Vice Chair All images are from the collections of History Colorado unless otherwise noted. From the Executive Director This has been a year of great fiscal news for History Colorado as we forged a path to a sound financial footing—a path that led to our eradication of a budget deficit and to new partnerships that helped us advance both our mission and our reach. -

FY 2020-21 Performance Plan

FY 2020-21 Performance Plan Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Letter from Executive Director 4 Our Path Forward 5 Our Path Forward 6 Organizational Chart and Financial Breakdown 7 Agency Description 8 Major Function Description - Unite as One History Colorado 9 Charting the path forward 12 Engage 1 million people annually by 2025 12 Build Long-Term Sustainability 12 Invest in Rural Prosperity 12 Strengthen Colorado Through Education 12 Share the Diverse Stories of Colorado 12 FY 2021 Strategic Policy Initiatives Forecast: Maximize Service to the State 13 #1 Wildly Important Goal — Engage One Million people Annually by 2025 13 Agency Business Priorities for FY 2020-21 14 FY 2020 Strategic Policy Initiatives Outcomes 17 Mission History Colorado creates a better future for Colorado by inspiring wonder in our past. Vision We are Colorado! We share powerful stories, honor treasured memories, and create vibrant communities. We are the trusted leaders in helping people understand what it means to be a Coloradan. Values We value: - The preservation of authentic stories, memories, artifacts, and places - New perspectives and experiences that connect people to the Rocky Mountain West - Curiosity and discovery - Critical thinking and inquiry - Inclusion and community - Hospitality and service - Nimbleness and innovation - Collaboration and cooperation - Financial stability - Excellence in everything we do - A willingness to experiment without fear of failure All images from the collections of History Colorado unless otherwise noted 2 | Page Letter from Executive Director Thank you for your interest in History Colorado's Performance Plan. History Colorado turns 141 years old this summer. As we collectively endure this historic pandemic, I’m especially mindful of the incredible legacy of our organization. -

Community-Wide Survey to Assess Perceptions, Intentions, and Attitudes on Safety & Visitation Post Reopening

DENVER CULTURAL ORGANIZATIONS: REOPENING SURVEY COMMUNITY-WIDE SURVEY TO ASSESS PERCEPTIONS, INTENTIONS, AND ATTITUDES ON SAFETY & VISITATION POST REOPENING 2020 As we continue to work our way through navigating the world during the COVID19 pandemic, arts and culture organizations face uncertainty. Despite the uncertainty, we continue to work together with our colleagues, donors, funders, staff, and elected officials to create plans that serve the needs of our communities. Information about the pandemic changes and evolves daily and we, as a Denver community, want to understand what is important to our guests as we work to re-open the doors to our institutions and organizations. While there are no concrete answers in a time like this, the Department of Community Research & Engagement Strategies at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science developed this pan-institutional study focused on our arts and culture community to create a shared, empirical picture around which our Denver cultural community could come together. We hope that these results support your continued re-opening efforts. It has been our honor to offer this small gesture of fellowship. Thank you for your willingness to be part of this study, we truly are all in this together. Andréa Giron Mathern Director of Community Research & Engagement Strategies Denver Museum of Nature & Science Denver Cultural Organization | 2 Collaboration © 2020 Thank you to the following Denver-area cultural organizations for their PARTICIPATING participation in this community-wide survey effort. ORGANIZATIONS Denver Cultural Organization **There were no responses received from the contacts from Four Mile Historic Park | 3 Collaboration © 2020 Denver cultural organizations led by the Community Research & Engagement TABLE OF Strategies team at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science developed a community-wide survey to assess intentions to visit, sentiments around proposed safety precautions, and impact on visitation and membership now CONTENTS that institutions have begun to reopen. -

Mags Harries PROFESSIONAL POSITION: 1978 ‐ School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, Sculpture Faculty

Mags Harries PROFESSIONAL POSITION: 1978 ‐ School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, Sculpture Faculty. 1990 ‐ Harries/Héder Collaborative, Cambridge MA AWARDS ‐ a Selection: 2010 Liveable City Vision Award for Esthetics: SunFlowers, An Electric Garden (Austin, TX) 2006 The Waterfront Center Honor Award of Excellence: WaterWorks at Arizona Falls (Phoenix, AZ) 2005 Valley Forward Crescordia Award: Arbors & Ghost Trees (Phoenix, AZ) 2004 AICA Award: Projections (NAO Gallery, Boston, MA) 2003 Valley Forward Presidential Award: WaterWorks at Arizona Falls (Phoenix, AZ) 2003 Individual Artist Grant ‐Sculpture/ Installation‐ Massachusetts Cultural Council 2001 Marshall Cogan Visiting Artist ‐ Office of the Arts at Harvard University, (Cambridge, MA) 1993 Boston Society of Architects Design Collaboration Award: Wall Cycle to Ocotillo (Boston, MA) 1992 Mayor's Office Artist Educators Civic Award (Boston, MA) 1986 Massachusetts Governor's Design Awards: Asaroton & Bellingham Square 1981 Design Excellence Award for Public Art in Transportation (N.E.A / U.S.D.O.T) 1977‐78 Bunting Institute Fellow, Radcliffe College, Harvard University, (Cambridge, MA) COMMISSIONS ‐ a Selection: * in collaboration with Lajos Héder 2010‐ City of Seattle, WA/ First Hill Streetcar Project* 2010‐ San Diego International Airport, San Diego, CA/ Performing Arts Venue* 2009‐ History Colorado Center, Denver, CO* 2009 Highline Canal, Phoenix, AZ / Zanjero’s Line with Ten Eyck Landscape Architects* 2009 Mueller Development, Austin, TX/ Sun Flowers, an Electric Garden -

Colorado Heritage Magazine

The Magazine of History Colorado Fall 2017 The Oberfelder Effect Bringing Talent to Denver Before Chuck Morris and Barry Fey Harvey Park: Building a John Cisco’s Shotgun and Stories Revealed in the Mid-Century Neighborhood Zoom In: The Centennial State Sunken Graves of Leadville’s for Denver in 100 Objects Evergreen Cemetery Steve Grinstead Managing Editor Micaela Cruce Editorial Assistance Darren Eurich, State of Colorado/IDS Graphic Designer The Magazine of History Colorado Fall 2017 Melissa VanOtterloo and Aaron Marcus Photographic Services 4 The Oberfelder Effect Colorado Heritage (ISSN 0272-9377), published by When Denver needed entertainers, Arthur and Hazel History Colorado, contains articles of broad general Oberfelder brought them to town and treated them right. and educational interest that link the present to the By Ellen Hertzman past. Heritage is distributed quarterly to History Colorado members, to libraries, and to institutions of 14 Evergreen Cemetery and Irish Colorado higher learning. Manuscripts must be documented when A historian reflects on his Irish American roots and the submitted, and originals are retained in the Publications mysteries inside a remote mountain cemetery. office. An Author’s Guide is available; contact the By James Walsh Publications office. History Colorado disclaims responsibility for statements of fact or of opinion Harvey Park Memories made by contributors. History Colorado also publishes 18 Explore, a bimonthy publication of programs, events, With postwar prosperity in Denver came bungalows and and exhibition listings. ranch homes, cul-de-sacs and car culture. By Shawn Snow, with Memories from Dean Reinfort Postage paid at Denver, Colorado All History Colorado members receive Colorado Heritage as a benefit of membership.