The Economic Power of Heritage and Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time Travelers

Sioux City Museum & Historical Association Members Your membership card is your passport to great Benefits Key: benefits at any participating Time Travelers C = Complimentary or discounted museum publication, gift or service museum or historic site across the country! D = Discounted admission P = Free parking F = Free admission R = Restaurant discount or offer Please note: Participating institutions are constantly G = Gift shop discount or offer S = Discounted special events O = Does not normally charge admission T = Free or discounted tour changing so calling ahead to confirm the discount is highly recommended. CANADA The Walt Disney Family Museum Georgia Indiana TIFF • (888)599-8433 San Francisco, CA • (415)345-6800 • Benefits: F American Baptist Historical Soc. • (678)547-6680 Barker Mansion Civic Center • (219) 873-1520 Toronto, ON • Benefits: C • tiff.net waltdisney.org Atlanta, GA • Benefits: C • abhsarchives.org Michigan, IN • Benefits: F T • barkermansion.com Twentynine Palms Historical Society Atlanta History Center • (404)814-4100 Brown County History Center USA Twentynine Palms • (760)367-2366 • Benefits: G Atlanta, GA • Benefits: F • atlantahistorycenter.com Nashville, IN • (812)988-2899 • Benefits: D G Alabama 29palmshistorical.com Augusta Museum of History • (706)722-8454 browncountyhistorycenter.org Berman Museum of World History USS Hornet Museum • (510)521-8448 Augusta, GA • Benefits: F G • augustamuseum.org Carnegie Center for Art & History Anniston, AL • (256)237-6261 • Benefits: D Alameda, CA • Benefits: D • uss-hornet.org -

Historic House Museums

HISTORIC HOUSE MUSEUMS Alabama • Arlington Antebellum Home & Gardens (Birmingham; www.birminghamal.gov/arlington/index.htm) • Bellingrath Gardens and Home (Theodore; www.bellingrath.org) • Gaineswood (Gaineswood; www.preserveala.org/gaineswood.aspx?sm=g_i) • Oakleigh Historic Complex (Mobile; http://hmps.publishpath.com) • Sturdivant Hall (Selma; https://sturdivanthall.com) Alaska • House of Wickersham House (Fairbanks; http://dnr.alaska.gov/parks/units/wickrshm.htm) • Oscar Anderson House Museum (Anchorage; www.anchorage.net/museums-culture-heritage-centers/oscar-anderson-house-museum) Arizona • Douglas Family House Museum (Jerome; http://azstateparks.com/parks/jero/index.html) • Muheim Heritage House Museum (Bisbee; www.bisbeemuseum.org/bmmuheim.html) • Rosson House Museum (Phoenix; www.rossonhousemuseum.org/visit/the-rosson-house) • Sanguinetti House Museum (Yuma; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/museums/welcome-to-sanguinetti-house-museum-yuma/) • Sharlot Hall Museum (Prescott; www.sharlot.org) • Sosa-Carrillo-Fremont House Museum (Tucson; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/welcome-to-the-arizona-history-museum-tucson) • Taliesin West (Scottsdale; www.franklloydwright.org/about/taliesinwesttours.html) Arkansas • Allen House (Monticello; http://allenhousetours.com) • Clayton House (Fort Smith; www.claytonhouse.org) • Historic Arkansas Museum - Conway House, Hinderliter House, Noland House, and Woodruff House (Little Rock; www.historicarkansas.org) • McCollum-Chidester House (Camden; www.ouachitacountyhistoricalsociety.org) • Miss Laura’s -

2017 Preliminary Conference Program Photo: VISIT DENVER Western Altitude / Western Attitude

Photo: VISIT DENVER MPMA Regional Museum Conference 64th Annual MPMA Conference October 15 - October 19 | Denver, CO Photo: ToddPowell Photo Credit VISITDENVER 2017 Preliminary Conference Program Photo: VISIT DENVER Western Altitude / Western Attitude Photo: VISIT DENVER Photo: VISIT DENVER/Steve Crecelius Western Altitude / Western Attitude Join in the conversation: #MPMA2017 Why Museums Are Needed Now More Than Ever Photo: VISIT DENVER/Steve Crecelius Invitation from the MPMA Conference Chairs Dear Colleagues and Friends: Join us this fall in Denver, Colorado…where the Rocky Mountains meet the Great Plains. What an appropriate place for the 2017 annual meeting of the Mountain-Plains Museums Association (MPMA), an organization where the museums of the mountains and plains come together. And MPMA even had its origins in this area. Here you will discover Western Altitudes and Western Attitude at our museums, historic sites, and within our people. John Deutschendorf was so impressed by Denver that he took it as his last name, becoming one of Colorado’s beloved balladeers, singing about our altitudes and our attitudes. John Denver wasn’t alone in his attraction to the area; millions have been rushing to the state since gold was discovered in 1859. What you will discover during our conference is that Denver is not just a single city but an entire region offering many great cultural resources as well as great scenic beauty. Our evening events will capitalize on the best that the Denver area has to offer. The opening event will be hosted in the heart of Denver by History Colorado, site of exhibits about Colorado’s history (including “Backstory: Western American Art in Context,” an exciting collaboration with the Denver Art Museum), and by the Clyfford Still Museum, where the works and life of one of the fathers of abstract expressionism are exhibited. -

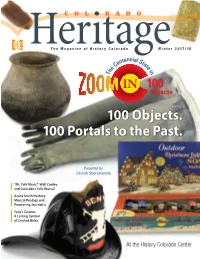

100 Objects. 100 Portals to the Past

The Magazine of History Colorado Winter 2017/18 100 Objects. 100 Portals to the Past. Presented by Colorado State University “Mr. Folk Music”: Walt Conley and Colorado’s Folk Revival Azalia Smith Hackley: Musical Prodigy and Pioneering Journalist Tony’s Conoco: A Lasting Symbol of Crested Butte At the History Colorado Center Steve Grinstead Managing Editor Micaela Cruce Editorial Assistance Darren Eurich, State of Colorado/IDS Graphic Designer The Magazine of History Colorado Winter 2017/18 Melissa VanOtterloo and Aaron Marcus Photographic Services How Did We Become Colorado? 4 Colorado Heritage (ISSN 0272-9377), published by The artifacts in Zoom In serve as portals to the past. History Colorado, contains articles of broad general By Julie Peterson and educational interest that link the present to the 8 Azalia Smith Hackley past. Heritage is distributed quarterly to History Colorado members, to libraries, and to institutions of A musical prodigy made her name as a journalist and activist. higher learning. Manuscripts must be documented when By Ann Sneesby-Koch submitted, and originals are retained in the Publications 16 “Mr. Folk Music” office. An Author’s Guide is available; contact the Walt Conley headlined the Colorado folk-music revival. Publications office. History Colorado disclaims By Rose Campbell responsibility for statements of fact or of opinion made by contributors. History Colorado also publishes 24 Tony’s Conoco Explore, a bimonthy publication of programs, events, A symbol of Crested Butte embodies memories and more. and exhibition listings. By Megan Eflin Postage paid at Denver, Colorado All History Colorado members receive Colorado Heritage as a benefit of membership. -

Colorado Women Take Center Stage

January/February 2020 Colorado Women Take Center Stage At the Center for Colorado Women’s History and Our Other Sites Interactives in What’s Your Story? help you find your superpower, like those of 101 influential Coloradans before you. Denver / History Colorado Center 1200 Broadway. 303/HISTORY, HistoryColoradoCenter.org ON VIEW NOW A Legacy of Healing: Jewish Leadership in Colorado’s Health Care Ballantine Gallery Sunlight, dry climate, high altitude, nutritious food, fresh air—that was the prescription for treating tuberculosis. As thousands flocked to Colorado for a cure, the Jewish community led the way in treatment. Co-curated by Dr. Jeanne Abrams from the University of Denver Libraries’ Beck Archives, A Legacy of Healing tells the story of the Jewish community’s involvement in revolutionizing our state’s health care in the late 19th and early 20th century. See rare film footage, medical tools and photographs from the top-tier Denver tuberculosis hospitals. Journey through the stories of Jewish leaders and ordinary citizens committed to caring for those in need. A Legacy of Healing honors the Jewish community for providing care to all Coloradans regardless of faith, race or social standing. NEW NEW & VIEW ON A Legacy of Healing is made possible through Rose Medical Center, the Chai (LIFE) Presenting Sponsor. The Education Sponsor is Rose Community Foundation. National Jewish Health, Mitzvah (Act of Kindness) Sponsor. ON VIEW NOW What’s Your Story? Owens Hickenlooper Leadership Gallery What’s your superpower? Is it curiosity—like the eleven-year-old who invented a way to test water for lead? Is it determination—like the first woman to work in the Eisenhower Tunnel? Generations have used their powers for good to create a state where values like innovation, collaboration and stewardship are celebrated. -

Colorado Stories: Interpreting History for Public Audiences at the History Colorado Center William Convery III

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-3-2012 Colorado Stories: Interpreting HIstory for Public Audiences at the History Colorado Center William Convery III Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Convery, William III. "Colorado Stories: Interpreting HIstory for Public Audiences at the History Colorado Center." (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/15 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i COLORADO STORIES: INTERPRETING COLORADO HISTORY FOR PUBLIC AUDIENCES AT THE HISTORY COLORADO CENTER BY William J. Convery III B.A., History, University of Colorado, Boulder, 1991 M.A., American Western History, University of Colorado, Denver, 1998 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2012 ii © 2012, William J. Convery III All Rights Reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The exhibits at the History Colorado Center reflect the work and dedication of an extensive team. Many, many people have contributed to the research, development, and writing of this exhibit over time. I want to thank History Colorado staffers Bridget Ambler, donnie betts, B. Erin Cole, Melissa de Bie, Barbara Dey, Jay Di Lorenzo, Deborah Espinosa, Sarah Gilmor, Shelia Goff, Steve Grinstead, Ben Fogelberg, Melanie Irvine, Abby Fisher Hoffman, April Legg, Becky Lintz, Moya Hansen, Beth Kaminsky, Rick Manzanares, Aaron Marcus, Lyle Miller, James Peterson, Elisa Phelps, J. -

July2017.Pdf

Benefits Key: C - Free or Discounted Gift, Publication, or Service D - Discounted Admission F - Free Admission G - Gift Shop Discount P - Free Parking R - Restaurant Discount S - Special Event Offer T - Free or Discounted Tour(s) It is highly recommended to call ahead and do your own independent research on any institution you plan to visit. Name City Benefit Alabama Berman Museum of World History Anniston D Alaska Arizona Arizona Historical Society - Arizona History Museum Tucson D Arizona Historical Society - Downtown History Museum Tuscon D Arizona Historical Society - Fort Lowell Museum Tuscon D Arizona Historical Society - Pioneer Museum Flagstaff D Arizona Historical Society - Sanguinetti House Museum Yuma D Arizona Historical Society Museum at Papago Park Tempe D Gila County Historical Museum Globe F, T, P Heritage Square Foundation Pheonix T Show Low Historical Museum Show Low F, G The Jewish History Museum Tucson F Arkansas Historic Arkansas Museum Little Rock F, P, G Old Independence Regional Museum Batesville F Rogers Historical Museum Rogers G, S Shiloh Museum of Ozark History Springdale G California Banning Museum Wilmington G Bonita Museum and Cultural Center Bonita F, G, P California Historical Society San Francisco F Catalina Island Museum Avalon F Dominguez Rancho Adobe Museum Rancho Dominguez F, G, S El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park Santa Barbara F Folsom History Museum Folsom F Friends of Rancho Los Cerritos Long Beach G, S Goleta Valley Historical Society Goleta F, G Heritage Square Museum Los Angeles -

History Colorado Annual Report 2010-11

Mapping Our Future 2010/2011 Annual Report HISTORY COLORADO CENTER Mission Statement As the designated steward of Colorado history, we aspire to engage people in our state’s heritage through collecting, preserving, and discovering the past in order to educate and provide perspectives for the future. 2010/ 2011 Annual Report CONTENTS Letter from the Chairman of the Board and the President | 2 Plans for the Future | 4 Partnerships Across the Map | 6 Charting New Territory | 8 At the Crossroads of History | 10 The State Historical Fund Annual Report | 11 History Colorado Awards | 19 The Geography of Learning | 20 The Volunteers of History Colorado | 22 Financial Summary | 24 Board of Directors | 25 History Colorado Preservation Awards | 26 History Colorado Staff | 27 Community Support | 30 Attendance | 33 On the cover: As visitors walk through the lobby and into the four-story Atrium of the new History Colorado Center, they’ll encounter a 40-by-60-foot interactive map of Colorado embedded in the floor. Drawing: ©2011 Steven Weitzman, Weitzman Studios Inc., and Tryba Architects All images from the collections of History Colorado unless otherwise noted. 2010/ 2011 Annual Report | 1 Mapping Our Future This year History Colorado engaged in a multitude of endeavors. And what better symbol of these than the 40-by-60-foot map of Colorado prominently placed in the Atrium floor of the new History Colorado Center? Here, myriad terrazzo colors combine to greet visitors as they enter this magnificent 21st-century building. But the map illustrates more than just Colorado’s diverse topography. It also serves as a subtle metaphor for the collaborative spirit between Colorado’s people and History Colorado’s staff. -

Colorado Byways Strategic Plan 2017

Strategic Plan for the Colorado Scenic and Historic Byways Commission It is with great pleasure and pride that the Colorado Scenic and Historic Byway Commissioners present our Strategic Plan to support the next three years of the program’s vision. The Colorado Scenic and Historic Byways program isn’t just a list of roads connecting one place to another. The 26 Byways have been carefully selected by the Commissioners to awe, instruct, delight, inform, physically challenge, soothe, and bolster the physical and spiritual health of the thousands of travelers who traverse Colorado’s chosen trails. There isn’t one formula that defines a Colorado Byway, but when you are driving, cycling, or walking on one of these routes you feel a “wow” factor that can’t be denied. Whether you are an outdoor recreationist, history buff, nature lover, tourist, or conservationist, you will recog- nize the work of devoted locals who share their bounty with you through resource stewardship. And that devotion is paid back to the local businesses, non-profits, and local citizens through renewed pride in their resources, community coalescence, and economic development. For the immediate future, the Commissioners want to chart innovative ways to support and guide Colorado’s Scenic and Historic Byways. Please join us in celebrating past accomplish- ments and envisioning new journeys. Colorado Scenic and Historic Byways Commission—January 2017 Silver Thread THE COLORADO SCENIC AND HISTORIC BYWAYS COMMISSION Rep. K.C. Becker, Chair: Representing the Robert John Mutaw: Rep. History Colorado Colorado General Assembly Jack Placchi: Rep. U.S. Bureau of Land Kelly Barbello: Rep. -

Strategic Plan 2021 Table of Contents

Strategic Plan 2021 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................. 2 Strategic Planning Process.......................................................... 3 Committee Members.................................................................... 4 Mission Statement........................................................................ 7 Our Values..................................................................................... 8 One-Year Vision Statement and Goals......................................... 10 Five-Year Vision Statement and Goals......................................... 12 Ten-Year Vision Statement and Goals.......................................... 14 Re-Evaluation of Strategic Plan.................................................... 15 Introduction Strategic Planning Process We have ended our tenth year on an upbeat note, despite a late start due to the coronavirus In 2019, HistoriCorps’ Board of Directors and Executive Director looked towards HistoriCorps’ tenth epidemic. Our team rose to the occasion, securing financial assistance from the Federal CARES Act year, our bright future, and agreed that we were overdue for a strategic plan. For many fledgling and developing effective protocols to keep our field staff and volunteers safe.e W owe thanks to our non-profit organizations, growth occurs so quickly that collaborative, long-term planning is sidelined; friends at the Forest Service, other Federal land management agencies and NGO partners who stood day-to-day -

Colorado Heritage Magazine

The Magazine of History Colorado Summer 2018 Baseball in Colorado Bringing America’s Pastime to the Centennial State Colorado’s Semi-Pro and Amateur “Bloomer Girls” Women’s Teams Chronicling the Bid for Pro Baseball Baseball Teams in Rare Photos Barnstorm the West in the Centennial State Steve Grinstead Managing Editor Alex Richtman Editorial Assistance Darren Eurich, State of Colorado/IDS Graphic Designer The Magazine of History Colorado Summer 2018 Aaron Marcus Photographic Services 4 Left on the Field Colorado Heritage (ISSN 0272-9377), published by History Colorado, contains articles of broad general Semi-pro and amateur ball teams live on in historic photographs. and educational interest that link the present to the By Alisa DiGiacomo past. Heritage is distributed quarterly to History Colorado members, to libraries, and to institutions of 20 “Bloomer Girls” Baseball Teams higher learning. Manuscripts must be documented when Women’s teams go barnstorming and find fans in Colorado. submitted, and originals are retained in the Publications By Ann Sneesby-Koch office. An Author’s Guide is available; contact the Publications office. History Colorado disclaims responsibility for statements of fact or of opinion Zooming in on Zoom In 25 made by contributors. History Colorado also publishes What was a license plate before there were license plates? Explore, a bimonthy publication of programs, events, and exhibition listings. A Way of Creating Meaning 26 Postage paid at Denver, Colorado An award-winning author looks at the role of early photography. A conversation with Rachel McLean Sailor All History Colorado members receive Colorado Heritage as a benefit of membership. -

Historic Site

PARACHUTE/BATTLEMENT MESA RIFLE AREA RIFLE/SILT AREA SILT/ NEW CASTLE AREA GLENWOOD SPRINGS AREA CARBONDALE AREA 4 RIFLE ARCH 8 RIFLE MTN. PARK/COMMUNITY 12 HIGHLAND CEMETERY AND 15 DOC HOLLIDAY MUSEUM 19 MAIN STREET CARBONDALE WHERE: North on Hwy 13 approximately 7 miles, HOUSE (CCC CAMP) VULCAN MINING MEMORIAL WHERE: Basement, Bullock’s, WHERE: Intersection of Main marked trail head with parking on right WHERE: 13885 County Road 217 (End of State Hwy WHERE: Take Castle Valley Blvd. to Club House Dr. to 732 Grand Ave., Street Carbondale WHAT: Natural Rock Arch on the Hogback 325—north of Rifle Falls Fish Hatchery) Cemetery Rd. (Lakota Ranch, north of City Market) Glenwood Springs and Hwy. 133, across WEBSITE: www.riflechamber.com WHAT: World class rock climbing extending for 2.5 WHEN: Available all day, every day WHEN: Store hours from City Market. CONTACT: Rifle Chamber miles in a spectacular boxed canyon. Hiking COST: Free WHAT: The Doc Holliday TIME: Access anytime of Commerce and ice caves. Visit the Rifle Community WHAT: The cemetery was established in 1888 and museum is a COST: Free (970) 625-2085 House that was built in the 1930s by the cemetery map is available at Town Hall, the satellite location WHAT: Historic buildings include The Dinkel Civilian Conservation Corp. Chamber of Commerce and the Historical for Glenwood Building, The IOOF Hall also known as the WEBSITE: www.rifleco.org/index.aspx?NID=91 Museum. The 1964 Vulcan Mine Memorial Springs Historical Rebekah Lodge, The Village Smithy and The CONTACT: (970) 665-6570 is also on display.