1 Notes for Chapter Eight 8–A: the Church's Supreme Authority Should

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jenkins to Fucinaro

+ JHS Vaticano 8 abril 2016 Querido hermano: Invocando la protección de la Sagrada Familia de Nazaret, me complazco de enviarle mi Exhortación “Amoris laetitia” por el bien de todas las familias y de todas las personas, jóvenes y ancianas, confiadas a su ministerio pastoral. Unidos en el Señor Jesús, con María y José, le pido que no se olvide de rezar por mí. Franciscus Texto de la Exhortación Apostólica: https://vaticloud.vatican.va/oc/public.php?service=files&t=bc83e4a00366ce2ddfa6be593a406d2e Materiales adicionales: 1- Síntesis: https://vaticloud.vatican.va/oc/public.php?service=files&t=23ba69811e9d948dd8e2c6d98077e465 2- Preguntas y respuestas: https://vaticloud.vatican.va/oc/public.php?service=files&t=c9c9f260b4e8bfea60ab29d2a2fbbfda Síntesis Amoris laetitia, sobre el amor en la familia “Amoris laetitia” (AL – “La alegría del amor”), la Exhortación apostólica post-sinodal “sobre el amor en la familia”, con fecha no casual del 19 de marzo, Solemnidad de San José, recoge los resultados de dos Sínodos sobre la familia convocados por Papa Francisco en el 2014 y en el 2015, cuyas Relaciones conclusivas son largamente citadas, junto a los documentos y enseñanzas de sus Predecesores y a las numerosas catequesis sobre la familia del mismo Papa Francisco. Todavía, como ya ha sucedido en otros documentos magisteriales, el Papa hace uso también de las contribuciones de diversas Conferencias episcopales del mundo (Kenia, Australia, Argentina…) y de citaciones de personalidades significativas como Martin Luther King o Eric Fromm. Es particular una citación de la película “La fiesta de Babette”, que el Papa recuerda para explicar el concepto de gratuidad. Premisa La Exhortación apostólica impresiona por su amplitud y articulación. -

Mary and Inter-Religious Dialogue 1/20/15 1:31 PM

Mary and Inter-religious Dialogue 1/20/15 1:31 PM With Vatican II’s “Declaration on the relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions Nostra Aetate” (NA) [link to: http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat- ii_decl_19651028_nostra-aetate_en.html of October 28, 1965 the Catholic Church has initiated her move toward other faiths by means of interreligious dialogue. The keyword ‘dialogue’ is important in this context since it applies to all cultures as well as faith traditions and respects the need for Inculturation. Moreover, NA explains that true dialogue “regards with sincere reverence those ways of conduct and of life, those precepts and teachings which, though differing in many aspects from the ones she holds and sets forth, nonetheless often reflect a ray of that Truth which enlightens all people (NA, 2). The effect of these encounters become increasingly apparent and is manifested by authentic esteem for the values and convictions in each religion. We can also observe a genuine exploration of common values as well as solicitude for the betterment of living conditions on earth. To foster the work of dialogue, Pope Paul VI set up the Secretariat for Non-Christians in 1964, recently renamed the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue. In 1991, to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of NA, the Pontifical Council for Inter-Religious Dialogue promulgated the document Dialogue and Proclamation–Reflection and Orientations on Interreligious Dialogue and the Proclamation of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/interelg/documents/rc_pc_interelg_doc_19051991_ dialogue-and-proclamatio_en.html] It highlights four forms of interreligious dialogue without claiming to establish any order of priority among them: a) The dialogue of life, where people strive to live in an open and neighborly spirit, sharing their joys and sorrows, their human problems and preoccupations. -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF THE HOLY FATHER POPE JOHN PAUL II TO THE MISSIONARIES OF INFINITE LOVE Friday, 4 September 1998 Dear Missionaries of Infinite Love, 1. Welcome to this meeting, which you desired in order to mark the 50th anniversary of the foundation of your secular institute. I extend my cordial greeting to each of you, with a special mention of fraternal affection for Bishop Luigi Bettazzi, who is accompanying you. He rightly wished to join you today as Bishop of the particular Church where the foundation took place, that is, the Diocese of Ivrea. In fact, the Work of Infinite Love originated in that land, made fertile at the beginning of this century by the witness of the Servant of God Mother Luisa Margherita Claret de la Touche, and it was from this work that your family was founded. Having obtained diocesan recognition in 1972, the institute was later approved by me for the whole Church. It is now present, in fact, in various parts of the world. Your basic sentiment in celebrating this anniversary is certainly one of thanksgiving, in which I am very pleased to join. 2. Dear friends, we are living in a year that is entirely dedicated to the Holy Spirit. Well, is the coincidence that you are celebrating the institute’s 50th anniversary in the year dedicated to the Holy Spirit not another special reason for gratitude? It is only because of the Spirit and in the Spirit that we can say: “God is love” (1 Jn 4: 8;16), a statement that constitutes the inexhaustible core, the well-spring of your spirituality. -

Solidarity As Spiritual Exercise: a Contribution to the Development of Solidarity in the Catholic Social Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eScholarship@BC Solidarity as spiritual exercise: a contribution to the development of solidarity in the Catholic social tradition Author: Mark W. Potter Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/738 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2009 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Theology SOLIDARITY AS SPIRITUAL EXERCISE: A CONTRIBUTION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOLIDARITY IN THE CATHOLIC SOCIAL TRADITION a dissertation by MARK WILLIAM POTTER submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 © copyright by MARK WILLIAM POTTER 2009 Solidarity as Spiritual Exercise: A Contribution to the Development of Solidarity in the Catholic Social Tradition By Mark William Potter Director: David Hollenbach, S.J. ABSTRACT The encyclicals and speeches of Pope John Paul II placed solidarity at the very center of the Catholic social tradition and contemporary Christian ethics. This disserta- tion analyzes the historical development of solidarity in the Church’s encyclical tradition, and then offers an examination and comparison of the unique contributions of John Paul II and the Jesuit theologian Jon Sobrino to contemporary understandings of solidarity. Ultimately, I argue that understanding solidarity as spiritual exercise integrates the wis- dom of John Paul II’s conception of solidarity as the virtue for an interdependent world with Sobrino’s insights on the ethical implications of Christian spirituality, orthopraxis, and a commitment to communal liberation. -

Virginal Chastity in the Consecrated Virgin

VIRGINAL CHASTITY IN THE CONSECRATED VIRGIN Thesis by Judith M. Stegman In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Theology Catholic Distance University 2014 Submitted July 14, 2014 Feast of St. Kateri Tekakwitha, Virgin Copyright © 2014 Judith M. Stegman All rights reserved ii to: The Most Holy Virgin Mary of Nazareth, Mother of our Lord Jesus Christ, Queen of Virgins, whose tender maternal and virginal love is the font of virginal chastity for all generations iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ………………………………………………………………………… 1 The question of virginal chastity …………………………………………... 1 The fiat of the Blessed Virgin Mary ……………………………………….. 2 The fiat of the consecrated virgin ………………………………………….. 4 Preparation of the Human Race for the Gift of Virginity ………………………….. 6 Virginity of the Most Holy Trinity ………………………………………… 6 Pre-Christian concept of virginity …………………………………………. 7 Christian understanding of virginal chastity ………………………………. 9 Christian Virginity as a Way of Life ………………………………………………. 16 Virgins of the early Church ………………………………………………... 16 Development of a rite of consecration to a life of virginity ……………….. 18 Renewal of the rite of consecration to a life of virginity for women living in the world ……………………………………….………… 22 A most excellent gift – the meaning of consecrated virginity in today’s Church ………………………………………………………….. 23 Virginal Chastity as the Essential Prerequisite for the Consecration of a Virgin …. 29 Prerequisites stated in the Praenotanda to the Rite of Consecration ……… 29 Virginal chastity: an essential prerequisite for consecration ………..……... 33 The gift of virginity ………………………………………………………… 36 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my special appreciation and thanks to my thesis advisor Dr. Robert Royal and to the dedicated professors at Catholic Distance University who have guided my studies in theology. -

TODO ESTÁ CONECTADO” Ecología Integral Y Comunicación En La Era Digital

Martín Carbajo Núñez “TODO ESTÁ CONECTADO” Ecología integral y comunicación en la era digital 1 Título de la obra: “Todo está conectado” Ecología integral y comunicación en la era digital Nombre del autor: Martín Carbajo Núñez © Martín Carbajo Núñez, 2019 Diseño y diagramación: - Diseño de cubierta: Juan Zelada - Imagen de portada: Shutterstock.com - Diagramación: Juan Zelada Editado por: © Asociación Hijas de San Pablo Jr. Callao 198, Lima, Perú Teléf.: 427-8276, Fax 426-9496 E-mail: [email protected] Primera edición, 2019 Tiraje: 3000 ejemplares Impreso por: EDITORIAL ROEL SAC Psje. Miguel Valcarcel N° 361, Ate, Lima Año de publicación: Octubre 2019 ISBN: Registro del Proyecto Editorial N.º Hecho el Depósito Legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú N.º 2 A Ascensión y María Ranilla, que me enseñaron a cuidar la tierra, y a mi padre Martín, cuya pasión por la radio despertó mi interés por la comunicación mediática. 3 SIGLAS Y ABREVIATURAS 1. Sagrada Escritura 1Cor 1.ª Corintios 2Cor 2.ª Corintios 1Jn 1.ª carta de Juan 1Pt 1.ª epístola de Pedro 2Pt 2.ª epístola de Pedro Ap Apocalipsis Col Colosenses Dt Deuteronomio Ef Efesios Ex Éxodo Ez Ezequiel Flp Filipenses Gal Gálatas Gn Génesis Heb Hebreos Is Isaías Jer Jeremías Jn Juan Lc Lucas Mc Marcos Mt Mateo Nm Números Rm Romanos Sal Salmos Sb Sabiduría Tt Tito 2. Magisterio eclesiástico AL Francisco, Exhortación Amoris Laetitia AN PCCS, Instrucción Aetatis Novae CA Juan Pablo II, Encíclica Centesimus annus CCC Catecismo de la Iglesia Católica CDSI PCJP, Compendio de la Doctrina Social -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF THE HOLY FATHER POPE JOHN PAUL II TO THE CONGREGATION FOR THE EVANGELIZATION OF PEOPLES DURING THEIR PLENARY ASSEMBLY Friday, 20 November 1998 Your Eminence, Venerable Brothers in the Episcopate, Dear Brothers and Sisters, 1. I am pleased to extend a cordial welcome to you all, members of the plenary assembly and officials of the Dicastery for the Evangelization of Peoples. I thank Cardinal Jozef Tomko for his kind words expressed also on behalf of those present. I greet each of you and thank you for your generous efforts in helping to spread the Gospel message. The theme of your plenary meeting this year deals with the “missionary dimension of institutes of consecrated life and societies of apostolic life”. A very important and timely subject, it closely follows the teaching contained in the Encyclical Redemptoris missio and the Apostolic Exhortation Vita consecrata. You have rightly focused your reflections on the role of consecrated life in the mission ad gentes. Indeed, this vast throng of monks, religious, members of religious and missionary institutes and societies of apostolic life has made a great contribution to evangelization. In the last century, large numbers of women religious also shared this missionary impulse, expressing by their particular charism the merciful face of God and the motherly heart of the Church. The history of every people has been affected by the presence of consecrated persons, by their witness, their work of charity and evangelization, and their sacrifice. And all this is not just past history. In mission territories there are still many religious priests; together with women religious and brothers they form the majority of the vital forces for mission. -

The Holy See

The Holy See MESSAGE OF JOHN PAUL II TO THE GENERAL DIRECTOR OF THE FRATERNITY OF DIOCESAN WORKER PRIESTS OF THE SACRED HEART OF JESUS I am pleased to address you on the occasion of the celebration in Rome of your 20th General Assembly at the Pontifical Spanish College of San José. Through you, I would also like to greet all the members of the Fraternity and to express my gratitude for your important ecclesial service, especially in the context of the pastoral care of vocations. I do so at the same time with the principal aim of encouraging you to take a daring and realistic look at the future to discern the new signs of the Kingdom, to give new life to your charism - one of those charisms which constitute the very marrow of the Church - and to respond to peoples' true aspirations and needs in giving their lives an orientation. Therefore, taking into account your own specific features and fully complying with my frequent appeal to redouble the pastoral care of vocations to the priesthood and the consecrated life, you described the main focus of your work in these days as: "The pastoral care of vocations, a challenge to our identity today". As Diocesan Worker Priests, you have always done your utmost in the pastoral care of priestly, religious and apostolic vocations, aware that they are the most universal and effective means of promoting all the other pastoral areas. This Assembly, therefore, must be an event of grace in which, by reaffirming your authentic institutional foundations, you can formulate the vitality, fruitfulness and radicalism that is still inherent in the charism you have inherited, to bring new and unheard of approaches to the sensitive work of vocations ministry. -

Priestly Formation According to Pastores Dabo Vobis* 1

305 ❚Special Issues❚ □ Priestly Formation in the Asian Contexts Priestly Formation According to Pastores Dabo Vobis* 1 Fr. Thomas Cheruparambil 〔St. Joseph Pontifical Seminary, India〕 Introduction 1. Historical Antecedents of Pastores Dabo Vobis 2. The 1990 Synod of Bishops: Some Particulars 3. Highlights on the Priestly Formation in Pastores Dabo Vobis 4. Biblical Foundation of Priesthood 5. Priestly Vocation and the Challenges of Priestly Formation 6. Human Formation 7. Spiritual Formation 8. Intellectual Formation 9. Pastoral Formation 10. Agents of Priestly Formation 11. Ongoing Formation of Priests Conclusion Introduction Jesus the high priest began his public ministry with the following proclamation: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me because he has anointed *1이 글은 2015년 ‘재단법인 신학과사상’의 연구비 지원을 받아 연구·작성된 논문임. 306 Priestly Formation in the Asian Contexts me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor” (Lk 4:18, 19). Jesus was filled with the Holy Spirit before his public ministry. All Christian faithful, irrespective of their sate of vocation are called to attain perfection and sanctity. As there are different kinds of vocations, the way to Christian perfection also differs. Every vocation and ministry is specific in its nature. Accordingly, one may speak about the specificity of priestly ministry and formation. In this connection, one may ask: what is the specific nature of priestly formation keeping in mind the specific nature of priestly ministry? There may be different views and opinions about priestly formation. -

Errazuriz, Il Diritto Canonico Nella Storia

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSITÀ DELLA SANTA CROCE TRATTATI DI DIRITTO 6 CORSO FONDAMENTALE SUL DIRITTO NELLA CHIESA I INTRODUZIONE I SOGGETTI ECCLESIALI DI DIRITTO di Carlos }. Erràzuriz M. MVLTA PAVCiS AG GIUFFRÈ EDITORE ABBREVIAZIONI Concilio Vaticano II, decreto Apostolicam actuosìtatem sull'apostolato dei laici, 18 novembre 1965 Ada Apostolicae Sedis (1909-) ad esempio Concilio Vaticano II, decreto Ad gentes sull'attività missionaria della Chiesa, 7 dicembre 1965 apostolica articolo Ada Sanctae Sedis (1865 -1908) canone (a meno che vi sia un'altra indicazione, si tratta di canoni del Co- dice di diritto canonico - latino - del 1983) capitolo Catechismo della Chiesa Cattolica (1992) Codex Canonum Ecclesiarum Orientalium promulgato da Giovanni Paolo II Q 18 ottobre 1990 cosiddetto(a) Concilio Vaticano II, decreto Christus Dominus sull'ufficio pastorale dei Vescovi, 28 ottobre 1965 GIOVANNI PAOLO II, esortazione apostolica post-sinodale Cbristifideles laici sulla vocazione e missione dei laici nella Chiesa e nel mondo, 30 di- cembre 1988, in AAS, 81 (1989), pp. 393-521 Codex Iuris Canonici promulgato da Giovanni Paolo II il 25 gennaio 1983 Codex luris Canonici promulgato da Benedetto XV il 15 settembre 1917 Congregazione per la Dottrina della Fede, Lettera Comunionis notio su alcuni aspetti della Chiesa intesa come comunione, 28 maggio 1992, in AAS, 86 (1993), pp. 838-850 Conciliorum oecumenicorum decreta, a cura di G. Alberigo ed altri e con la consulenza di H. Jedin, EDB, Bologna 1991 Communicationes (1969-) (rivista della Pontificia Commissione per la re- visione del CIC, denominata successivamente Pontificia Commisione per l'interpretazione del CIC, Pontificio Consiglio per l'interpretazione dei Testi Legislativi, e attualmente Pontificio Consiglio per i Testi Legisla- tivi). -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS OF THAILAND ON THEIR "AD LIMINA" VISIT Castel Gandolfo - Friday, 30 August 1996 Dear Brother Bishops, 1. It is a great joy for me to welcome you, the members of the Bishops' Conference of Thailand, on the occasion of your ad Limina visit to the Apostolic See, faithful depositary of the preaching and supreme witness of the Princes of the Apostles, Peter and Paul. I am convinced that our meetings of these days will further strengthen the bonds of unity, charity and peace which bring us together in the communion of Christ's Body - the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church. In particular I wish to thank Cardinal Michai Kitbunchu for the cordial greetings which he conveyed on behalf of the priests, consecrated men and women, and the lay faithful of the Church in Thailand. From my Pastoral Visit to your country 12 years ago I retain vivid memories of your people's courteous hospitality and enterprising vitality, their spirit of tolerance, their unbounded generosity to refugees and strangers, their ethnic and cultural richness, and their profound religious sense. With joy I remember the warm welcome of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej; and on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of his accession to the throne I wish to acknowledge his role in guaranteeing Thailand's tradition of religious freedom and his promotion of the lofty ideals of social justice and solidarity. 2. Dear Brothers, reflecting on your ministry I cannot but recall what the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council taught so incisively, namely that the Church is "missionary by her very nature" (Ad Gentes, 2). -

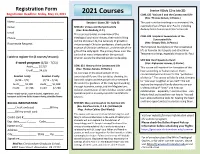

2021 Registration Form

Registration Form Session II (July 12 to July 23) Registration Deadline: Friday, May 14, 2021 2021 Courses CONL 625 Vatican II and the Consecrated Life (Rev. Thomas Nelson, O.PRAEM.) Name ________________________________ Session I (June 28 – July 9) The post-conciliar teaching on consecrated life, Order ________________________________ SPIR 634 Virtues and the Spiritual Life especially that of Pope John Paul II, including (Rev. Brian Mullady, O.P.) Redemptionis Donum and Vita Consecrata. Email________________________________ This course provides an overview of the theological and moral virtues, their role in living CONL 623 Scriptural Foundations of the Phone _______________________________ Consecrated Life out the Christian life, the necessity of growth in (Rev. Gregory Dick, O.PRAEM.) Roommate Request: virtue to reach Christian perfection, charity as the essence of Christian perfection, and the role of the The Scriptural foundations of the consecrated _____________________________________ gifts of the Holy Spirit. The primary focus is on the life as found in the Gospels and other New cardinal or moral virtues which the spiritual Testament writings, especially those of St. Paul. I wish to register for (2 courses/session): director assists the directed person to develop. SPIR 803 Heart Speaks to Heart 4-week program (6/28 - 7/23) (Rev. Alphonsus Hermes, O.PRAEM.) CONL 621 History of the Consecrated Life Audit____ $2,310 This course will examine the formation of the (Rev. Thomas Nelson, O.PRAEM.) Credit____ $4,526 heart according to human