Trade Liberalization, Labor Allocation and Income Dynamics in Vietnam Hoang Dat Vu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impacts of Trade Liberalization on Labor Allocation in Viet Nam1

Impacts of trade Liberalization on labor allocation in Viet Nam1 Draft version, please do not quote Vu Hoang Dat Centre for Analysis and Forecasting (CAF), Viet Nam Academy of Social Sciences (VASS) and Développement, Institutions et Mondialisation (DIAL), Laboratoire d'Économie de Dauphine (LEDa), Université Paris-Dauphine Abstract This study investigate impacts of trade liberalization on employment allocation across different types including self-employment, wage work in household businesses and those in formal sectors of private, foreign invested and state ones. Extensions of the two-step specification and the one-equation specification of the model in Goldberg and Pavcnik (2003) are employed to answer the question empirically. Data is sourced from five Viet Nam Household Living Standard Surveys from 2002 to 2010 and available measures of the trade liberalization in Viet Nam. The results indicate that there are no significant impacts of trade liberalization on relative allocation between the wage work in the formal sectors and those in household businesses and the results are mixed for the impacts on the allocation between the wage work in the formal sectors and the self-employment. Keywords: Trade liberalization, labor allocation, informality, Vietnam. 1 The paper is based on a part of a research implemented with a research grant and technical support from the Mekong Economic Research Network (MERN) - managed by the Centre for Analysis and Forecasting (CAF) of the Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences (VASS) with financial support from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Canada. The author is grateful to Pham Minh Thai (CAF, VASS), Phan Thi Song Thuong (MPI/KDI), Vu Thi Thu Thuy (GSO) and Vu Thi Van Ngoc (CAF/VASS) for their comments/contributions in early state of the research. -

ABBYY Data Capture Technology Optimizes Loan Processing in Vietnam Foreign Trade Bank

Success Story ABBYY Data Capture Technology Optimizes Loan Processing in Vietnam Foreign Trade Bank «We have been trying to find a data capture solution for many years but up to this time no product could meet our demands. Although we know that there are many data capture solutions, the matter is that no solution can recognize Vietnamese and therefore they can not capture data from Vietnamese documents effectively. And ABBYY FlexiCapture is the best solution we have ever seen.» – says the director of the center of credits and loans Mr. Hung, the Bank for Foreign Trade of Vietnam. About Bank for Background Foreign Trade of Vietnam economy is based on work of small and medium enterprises. In spite Vietnam (VCB) of this fact an entrepreneur should have quite a large sum to start his business, and that is not always possible. And here banks come to help. The banking VCB is the oldest and the biggest commercial bank for external affairs system plays a very important role in the operation of businesses, because 50% with branches located all over of their capital comes from the bank loans . One of the biggest banks to provide Vietnam. The bank is the full member loans for enterprise customers is the Bank for Foreign Trade of Vietnam (VCB) – of Vietnam Bankers Association, the oldest commercial bank. The bank has always been known as the most Asia Bankers Association, SWIFT, prestigious bank in trade, finance, international payments and other banking Visa, MasterCard and the leading commercial bank in trade finance, and financial services, including loans for businesses. -

Monetary Policy in Vietnam

Monetary Policy in Vietnam: Alternatives to Inflation Targeting Le Anh Tu Packard ([email protected]) Fifth Draft July 2007 Paper prepared for the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst with support from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). Earlier versions of this paper were presented to the May 2005 CEDES/Amherst Research Conference in Buenos Aires and the July 2005 Da Nang Symposium on Continuing Renovation of the Economy and Society. Financial support for this project has been provided by the Ford Foundation, UNDESA, and the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation. My gratitude and thanks go to two anonymous referees, Gerald Epstein, Erinc Yeldan, Jaime Ros, Lance Taylor, Per Berglund, and Phillipe Scholtes for their insightful comments and valuable ideas, and also to numerous colleagues in Vietnam including Dang Nhu Van for their helpful feedback. I am responsible for all remaining errors and omissions. List of Acronyms and Abbreviations ASEAN Association of South East Asian Nations BFTV Bank for Foreign Trade of Vietnam BIDV Bank for Investment and Development of Vietnam CEPT Common Effective Preferential Tariff CIEM Central Institute for Economic Management CMEA Council of Mutual Economic Assistance CPRGS Comprehensive Poverty Reduction and Growth Strategy DAF Development Assistance Fund FDI Foreign Direct Investment FIE Foreign-Invested Enterprise GC General Corporation GDI Gender-related Development Index GDP Gross Domestic Product GNP Gross National -

Finance & Business News

finance & business news 28 February 2017 FINANCE . 1 Khanh Hoa calls for increased economic cooperation with SBV announces compulsory M&A for weak banks 1 US, Russia 30 Credit grows strongly in Jan 3 Low-cost apartment developers face big challenges 30 Banks eye higher credit growth, profits 3 BIZ NEWS . 31 Vietnamese banks overly dependent on credit growth 3 Business Briefs February 28, 2017 31 Anti-dollarisation efforts face challenges 4 Shares up on investor confidence 32 Dividends: should shareholders sympathise with banks? 5 Shares inch up on blue chips 32 Financial leasing companies hard-pressed for foreign capital 6 All indexes close up 33 Voluntary social insurance attracts little interest 7 VietJet stock jumps 20 pct on debut - exchange 33 Non-life insurers cautiously set 2017 growth target 8 PENM IV Germany to buy HPG shares 34 Vietnam bank tycoon, former executives face trial over $66 HSX puts 21.6mn PVB shares on warning list 34 million losses 9 First local realty investment trust debuts on bourse 34 VNPT to sell stake at Maritime Bank 10 Market correction seen continuing into this week 35 Credit and land policies for agriculture should be loosened 10 Japanese prefecture seeks opportunity in Vietnam 36 Collecting taxes from online stores possible -- experts 11 Vegetable, fruit exports to struggle 36 Big credit contract secured for Cam Ranh airport's terminal Agro-forestry-fishery export value increases 37 project 12 Deputy PM pushes for VNPT's divestment 38 Reference exchange rate revised up 4 dong 12 Vietnam attends India-CLMV -

Trade and Sustainable Development in Vietnam

Trade and Sustainable Development in Vietnam IISD is producing this paper as part of its capacity building program for developing countries on the issues of trade and sustainable development – the Trade Knowledge Network Project. This work was carried out with the aid of a grant from the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada. The full version of this research, and the work of other members of the Trade Knowledge Network, is available on IISDnet at http://iisd.ca/tkn/default.htm. The Knowledge Networks Project aims to build capacity in developing countries to address the issues of trade and sustainable development. It consists of three main areas of work: domestic-level research and workshops on the linkages between trade and sustainable development at the local and international levels; additional research on cross-cutting themes of interest to developing country policy-makers; and the linking of developing country research institutions in a trade and sustainable development knowledge network. For more information on the Trade Knowledge Network Project, see http://iisd.ca/tkn/default.htm, or contact IISD at [email protected]. IISD contributes to sustainable development by advancing policy recommendations on international trade and investment, economic instruments, climate change, measurement and indicators, and natural resource management. Using Internet communications, we report on international negotiations and broker knowledge gained through collaborative projects with global partners, resulting in more rigorous research, capacity building in developing countries and better dialogue between North and South. IISD’s vision is better living for all -- sustainably; its mission is to champion innovation, enabling societies to live sustainably. -

A Study on Foreign Direct Investment Flows in Vietnam

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 13, Issue 6, 2020 A Study on Foreign Direct Investment Flows in Vietnam Van Su Haa*, Thu Thuy Nguyenb, aAssociate Professor, Faculty of Economics & Law, Thuongmai University, Vietnam, bAssociate Professor, Faculty of Financial & Banking, Thuongmai University, Vietnam, Email: a*[email protected], [email protected] Integration is forecasted to have a substantial impact on not only import and export activities but also on the ability to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) into Vietnam. Our regression results show that trade openness has a positive impact on Vietnam’s inward FDI (an increase of 1.0% in trade liberalisation can result in an increase of 0.23% in FDI inflows to Vietnam). Notably, our simulation results reveal that the CPTPP will increase the growth rate of FDI into Vietnam from 2.0% -2.4%/ year compared to the base scenario. However, the degree of impact will vary over time. Between 2019 and 2025, FDI inflows will tend to increase faster than in the following period 2026-2035. This shows that CPTPP will have a faster and stronger impact in the first 6 years (2019-2025) (with a steeper impact curve) when the agreement officially takes effect for Vietnam. Then the impact will decrease gradually in the following years. Key words: The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Vietnam. Introduction On March 8, 2018, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) was officially signed in Santiago, the capital of Chile with 11 member countries (including Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam). -

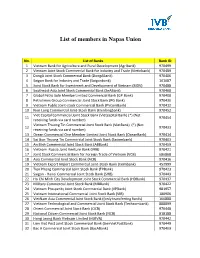

List of Members in Napas Union

List of members in Napas Union No. List of Banks Bank ID 1 Vietnam Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (Agribank) 970499 2 Vietnam Joint Stock Commercial Bank for Industry and Trade (Vietinbank) 970489 3 DongA Joint Stock Commercial Bank (DongABank) 970406 4 Saigon Bank for Industry and Trade (Saigonbank) 161087 5 Joint Stock Bank for Investment and Development of Vietnam (BIDV) 970488 6 Southeast Asia Joint Stock Commercial Bank (SeABank) 970468 7 Global Petro Sole MemberLimited Commercial Bank (GP.Bank) 970408 8 Petrolimex Group Commercial Joint Stock Bank (PG Bank) 970430 9 Vietnam Public Joint-stock Commercial Bank (PVcomBank) 970412 10 Kien Long Commercial Joint-Stock Bank (Kienlongbank) 970452 Viet Capital Commercial Joint Stock Bank (Vietcapital Bank) (*) (Not 11 970454 receiving funds via card number) Vietnam Thuong Tin Commercial Joint Stock Bank (VietBank) (*) (Not 12 970433 receiving funds via card number) 13 Ocean Commercial One Member Limited Joint Stock Bank (OceanBank) 970414 14 Sai Gon Thuong Tin Commercial Joint Stock Bank (Sacombank) 970403 15 An Binh Commercial Joint Stock Bank (ABBank) 970459 16 Vietnam Russia Joint Venture Bank (VRB) 970421 17 Joint Stock Commercial Bank for Foreign Trade of Vietnam (VCB) 686868 18 Asia Commercial Joint Stock Bank (ACB) 970416 19 Vietnam Export Import Commercial Joint-Stock Bank (Eximbank) 452999 20 Tien Phong Commercial Joint Stock Bank (TPBank) 970423 21 Saigon - Hanoi Commercial Joint Stock Bank (SHB) 970443 22 Ho Chi Minh City Development Joint Stock Commercial Bank (HDBank) -

Restructuring the Banking System: the Case of Vietnam

Review of Business and Economics Studies Volume 4, Number 4, 2016 Restructuring the Banking System: the Case of Vietnam To Thuy Duong, Banking Academy of Vietnam, 12, Chua Boc Street, Dong Da District, Hanoi, Vietnam [email protected] Abstract. This paper aims at studying the restructuring of commercial banks that has been started since 2008 in Vietnam by analysing in two angles: Effi ciency and Stability of the banking system. Firstly, the paper applies a modifi ed Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) model in 2 cases to estimate the changes of the effi ciency by analyse the E-scores of 26 commercial banks from 2008 to 2012 and examine the profi ts and productions effi ciency of 7 DMUs of the Vietnamese banking system in 2 years 2011 and 2013. Secondly, this study will calculate the Z-scores and T-test by using SPSS program to assess the stability of the banking system. Moreover, this study uses quantitative and qualitative methods to assess and quantify the results of the Vietnam commercial banks’ restructuring under the Decision No. 254/QD-TTg. The results showed that Vietnamese banking system remained stable during the process and contributed to economic growth, however the results were quite limited and lacks of long-term effects, such as many restructuring objectives were not achieved thorough handling bad debt, cross-ownership, improving governance and enhance the operational effi ciency of commercial banks. In particular, the major cause of these problems is due to the lack of a general approach to the overall handling of the issue of restructuring commercial banking system, particularly is missing a legal framework for the systematic implementation of the restructuring process in the context of economic restructure. -

Company Profile

COMPANY PROFILE CREDIT RATING OF VIETNAM JOINT STOCK COMPANY (CRV) 11 Hanoi, 2019 DESCRIPTION Full name: The Credit Rating of Vietnam Joint Stock Company Short name : CRV Address: 108, A14, Group 29, 100 Tran Dai Nghia Street – Dong Tam Ward – Hai Ba Trung – Hanoi Office: 2nd Floor, 57 Hang Chuoi Str. – Hai Ba Trung – Hanoi Telephone number: 84-24-3944-8809 Fax: 84-24-3971-0982 Website: http://www.crv.com.vn Email: [email protected] Background: CRV is an independent research and consultant company founded by professional researchers and consultants who have earned doctoral degrees in Development Economics and Economic Mathematics from various countries. CRV strives to be one of the leading research and consultancy institutions in the areas of social- economic policy and finance, re-structural enterprises, poverty and social protection, impact evaluation in the country. CRV is one of the best provider of services concerning independent credit rating, constructing credit rating indicators, risk analyses and evaluations, investment researches, and data of businesses. Our company’s desire is to provide investors with standard, independent, and objective evaluations, which help them make financial investment decisions more confidently and certainly. Therefore, CRV always want to be on the same side with the investors under the slogan “Together approaching the true value of information”. CRV provides services to development agencies, non-government organizations and corporate clients. CRV approach combines in-depth knowledge of the institutional and cultural environments with international standard technical assistance based on thorough economic, socio-economic analysis and quantitative analysis, since 2007 CRV has implemented some projects. -

Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement on Foreign Direct Investment Attraction and Foreign Trade of Vietnam

ASSESSMENT OF THE 10-YEAR IMPACT OF THE UNITED STATES- VIETNAM BILATERAL TRADE AGREEMENT ON FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT ATTRACTION AND FOREIGN TRADE OF VIETNAM Hoang Chi Cuong 1, 2, *, Ph.D. 1Hai Phong Private University, Business Administration Department 2Vietnamese Fulbright Scholar, Postdoctoral Fellowship at School of Public and Environmental Affairs, Indiana University Bloomington, the USA *E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This study employs gravity model and a panel dataset of country pairs which involves 17 FDI and trade partners of Vietnam including Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Japan, Malaysia, Netherlands, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, United Kingdom, and the U.S. in the period from 1995 to 2011. This is to examine the possible impacts of the USBTA on FDI inflows and exports and imports of Vietnam. The estimation results indicate that the USBTA has not induced FDI inflows into Vietnam but it has significant impact on expending both exports and imports of the country. Key words: exports, FDI, gravity model, Hausman-Taylor estimation, imports, USBTA, Vietnam 1. INTRODUCTION On 13 July 2000, the United States and Vietnam signed a sweeping bilateral trade agreement (USBTA) after 5 years since two countries have normal diplomatic relation in 1995. Following affirmative votes in Congress and the Vietnamese National Assembly, the USBTA entered into force on 10 December 2001, when the two countries formally exchanged letters implementing the agreement. Under this Deal, the United States will extend temporary most favored nation status (MFN, also known as normal trade relations [NTR] status) to Vietnam, a step that will significantly reduce U.S. -

Vietnam-China Trade Relations in the Feudal Period

doi: 10.14456/jms.2015.20 Vietnam-China Trade Relations in the Feudal Period: From the Early 10th to the Late 19th Century Nguyen Thi My Hanha* aFaculty of Vietnamese Studies, Hanoi National University of Education 136 Xuan Thuy street, Cau Giay District, Hanoi, Vietnam *Corresponding author. Tel: (+84) 0936121816/ 0913434139 Email: [email protected] Abstract During the thousands of years that Vietnam and China existed side by side, trade relations between them, despite fluctuations at different times, continued without interruption. History reveals that trade relations between the two countries were always strongly affected by political relations. This article aims to understand trade relations from the 10th century until 1885, when Vietnam emerged as an independent country after having been an administrative district of the Chinese feudal dynasty. The Treaty of Tianjin, which was signed between France and China in 1885, gave France control over Annam, as Vietnam was then known, and marked the permanent termination of the vassal relationship between Vietnam and China. This paper suggested that Vietnam trade relations with China during the 10th century until 1885 followed the principle of being firm but flexible in order to maintain conciliatory relations with China, as China was considered Vietnam’s main partner in both political and economic relations. The state of Vietnam-China economic relations fluctuated during different feudal dynasties. Certain dynasties maintained a closed-door policy; however, trade between two countries still took place by traders especially in border areas. This indicated that trade relations at border crossings or trading sites on land and at sea was stronger and more active than formal trade relations. -

CFA Society Vietnam Foreign Trade University Ho Chi Minh City Campus

CFA Institute Research Challenge Hosted by CFA Society Vietnam Foreign Trade University Ho Chi Minh City Campus The CFA Institute Research Challenge is a global competition that tests the equity research and valuation, investment report writing, and presentation skills of university students. The following report was submitted by a team of university students as part of this annual educational initiative and should not be considered a professional report. Disclosures: Ownership and material conflicts of interest The author(s), or a member of their household, of this report does not hold a financial interest in the securities of this company. The author(s), or a member of their household, of this report does not know of the existence of any conflicts of interest that might bias the content or publication of this report. Receipt of compensation Compensation of the author(s) of this report is not based on investment banking revenue. Position as an officer or a director The author(s), or a member of their household, does not serve as an officer, director, or advisory board member of the subject company. Market making The author(s) does not act as a market maker in the subject company’s securities. Disclaimer The information set forth herein has been obtained or derived from sources generally available to the public and believed by the author(s) to be reliable, but the author(s) does not make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy or completeness. The information is not intended to be used as the basis of any investment decisions by any person or entity.