Psychological Reflections on Mahatma Gandhi and the Future of Satyagraha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi's Experiments with the Indian

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi’s Experiments with the Indian Economy, c. 1915-1965 by Leslie Hempson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Co-Chair Professor Mrinalini Sinha, Co-Chair Associate Professor William Glover Associate Professor Matthew Hull Leslie Hempson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5195-1605 © Leslie Hempson 2018 DEDICATION To my parents, whose love and support has accompanied me every step of the way ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ACRONYMS v GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS vi ABSTRACT vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE AGRO-INDUSTRIAL DIVIDE 23 CHAPTER 2: ACCOUNTING FOR BUSINESS 53 CHAPTER 3: WRITING THE ECONOMY 89 CHAPTER 4: SPINNING EMPLOYMENT 130 CONCLUSION 179 APPENDIX: WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 183 BIBLIOGRAPHY 184 iii LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 2.1 Advertisement for a list of businesses certified by AISA 59 3.1 A set of scales with coins used as weights 117 4.1 The ambar charkha in three-part form 146 4.2 Illustration from a KVIC album showing Mother India cradling the ambar 150 charkha 4.3 Illustration from a KVIC album showing giant hand cradling the ambar charkha 151 4.4 Illustration from a KVIC album showing the ambar charkha on a pedestal with 152 a modified version of the motto of the Indian republic on the front 4.5 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing the charkha to Mohenjo Daro 158 4.6 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing -

Friends of Gandhi

FRIENDS OF GANDHI Correspondence of Mahatma Gandhi with Esther Færing (Menon), Anne Marie Petersen and Ellen Hørup Edited by E.S. Reddy and Holger Terp Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum, Berlin The Danish Peace Academy, Copenhagen Copyright 2006 by Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum, Berlin, and The Danish Peace Academy, Copenhagen. Copyright for all Mahatma Gandhi texts: Navajivan Trust, Ahmedabad, India (with gratitude to Mr. Jitendra Desai). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transacted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum: http://home.snafu.de/mkgandhi The Danish Peace Academy: http://www.fredsakademiet.dk Friends of Gandhi : Correspondence of Mahatma Gandhi with Esther Færing (Menon), Anne Marie Petersen and Ellen Hørup / Editors: E.S.Reddy and Holger Terp. Publishers: Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum, Berlin, and the Danish Peace Academy, Copenhagen. 1st edition, 1st printing, copyright 2006 Printed in India. - ISBN 87-91085-02-0 - ISSN 1600-9649 Fred I Danmark. Det Danske Fredsakademis Skriftserie Nr. 3 EAN number / strejkode 9788791085024 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ESTHER FAERING (MENON)1 Biographical note Correspondence with Gandhi2 Gandhi to Miss Faering, January 11, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, January 15, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, March 20, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, March 31,1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, April 15, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, -

1. Letter to Children of Bal Mandir

1. LETTER TO CHILDREN OF BAL MANDIR KARACHI, February 4, 1929 CHILDREN OF BAL MANDIR, The children of the Bal Mandir1are too mischievous. What kind of mischief was this that led to Hari breaking his arm? Shouldn’t there be some limit to playing pranks? Let each child give his or her reply. QUESTION TWO: Does any child still eat spices? Will those who eat them stop doing so? Those of you who have given up spices, do you feel tempted to eat them? If so, why do you feel that way? QUESTION THREE: Does any of you now make noise in the class or the kitchen? Remember that all of you have promised me that you will make no noise. In Karachi it is not so cold as they tried to frighten me by saying it would be. I am writing this letter at 4 o’clock. The post is cleared early. Reading by mistake four instead of three, I got up at three. I didn’t then feel inclined to sleep for one hour. As a result, I had one hour more for writing letters to the Udyoga Mandir2. How nice ! Blessings from BAPU From a photostat of the Gujarati: G.N. 9222 1 An infant school in the Sabarmati Ashram 2 Since the new constitution published on June 14, 1928 the Ashram was renamed Udyoga Mandir. VOL.45: 4 FEBRUARY, 1929 - 11 MAY, 1929 1 2. LETTER TO ASHRAM WOMEN KARACHI, February 4, 1929 SISTERS, I hope your classes are working regularly. I believe that no better arrangements could have been made than what has come about without any special planning. -

1. WHAT SHOULD BE DONE WHERE LIQUOR IS BEING SERVED? a Gentleman Asks in Sorrow:1 I Am Not Aware of Liquor Having Been Served at the Garden Party

1. WHAT SHOULD BE DONE WHERE LIQUOR IS BEING SERVED? A gentleman asks in sorrow:1 I am not aware of liquor having been served at the garden party. However, I would have attended it even if I had known it. A banquet was held on the same day. I attended it even though liquor was served there. I was not going to eat anything at either of these two functions. At the dinner a lady was sitting on one side and a gentleman on the other side of me. After the lady had helped herself with the bottle it would come to me. It would have to pass me in order to reach the gentleman. It was my duty to pass it on to the latter. I deliberately performed my duty. I could have easily refused to pass it saying that I would not touch a bottle of liquor. This, however, I considered to be improper. Two questions arise now. Is it proper for persons like me to go where drinks are served ? If the answer is in the affirmative, is it proper to pass a bottle of liquor from one person to another? So far as I am concerned the answer to both the questions is in the affirmative. It could be otherwise in the case of others. In such matters, I know of no royal road and, if there were any, it would be that one should altogether shun such parties and dinners. If we impose any restrictions with regard to liquor, why not impose them with regard to meat, etc.? If we do so with the latter, why not with regard to other items which we regard as unfeatable? Hence if we look upon attending such parties as harmful in certain circumstances, the best way seems to give up going to all such parties. -

Gandhi Wields the Weapon of Moral Power (Three Case Stories)

Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power (Three Case Stories) By Gene Sharp Foreword by: Dr. Albert Einstein First Published: September 1960 Printed & Published by: Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) Phone: 079 – 27540635 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power FOREWORD By Dr. Albert Einstein This book reports facts and nothing but facts — facts which have all been published before. And yet it is a truly- important work destined to have a great educational effect. It is a history of India's peaceful- struggle for liberation under Gandhi's guidance. All that happened there came about in our time — under our very eyes. What makes the book into a most effective work of art is simply the choice and arrangement of the facts reported. It is the skill pf the born historian, in whose hands the various threads are held together and woven into a pattern from which a complete picture emerges. How is it that a young man is able to create such a mature work? The author gives us the explanation in an introduction: He considers it his bounden duty to serve a cause with all his ower and without flinching from any sacrifice, a cause v aich was clearly embodied in Gandhi's unique personality: to overcome, by means of the awakening of moral forces, the danger of self-destruction by which humanity is threatened through breath-taking technical developments. The threatening downfall is characterized by such terms as "depersonalization" regimentation “total war"; salvation by the words “personal responsibility together with non-violence and service to mankind in the spirit of Gandhi I believe the author to be perfectly right in his claim that each individual must come to a clear decision for himself in this important matter: There is no “middle ground ". -

The Epic Fast

The Epic Fast The Epic Fast By : Pyarelal First Published: 1932 Printed & Published by: Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) Phone: 079 – 27540635 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org www.mkgandhi.org Page 1 The Epic Fast To The Down-Trodden of the World www.mkgandhi.org Page 2 The Epic Fast PUBLISHER'S NOTE This book was first published in 1932 i.e. immediately after Yeravda Pact. Reader may get glimpses of that period from the Preface of the first edition by Pyarelal Nayar and from the Foreward by C. Rajagopalachari. Due to the debate regarding constitutional provisions about reservation after six decades of independence students of Gandhian Thought have been searching the book which has been out of print since long. A publisher in Tamilnadu has asked for permission to translate the book in Tamil and for its publication. We welcomed the proposal and agreed to publish the Tamil version. Obviously the original book in English too will be in demand on publication of the Tamil version. Hence this reprint. We are sure, this publication will help our readers as a beacon light to reach out to the inner reaches of their conscience to find the right path in this world of conflicting claims. In this context, Gandhiji's The Epic Fast has no parallel. 16-07-07 www.mkgandhi.org Page 3 The Epic Fast PREFACE OF THE FIRST EDITION IT was my good fortune during Gandhiji's recent fast to be in constant attendance on him with Sjt. Brijkishen of Delhi, a fellow worker in the cause. -

1. RAJKOT the Struggle in Rajkot Has a Personal Touch About It for Me

1. RAJKOT The struggle in Rajkot has a personal touch about it for me. It was the place where I received all my education up to the matricul- ation examination and where my father was Dewan for many years. My wife feels so much about the sufferings of the people that though she is as old as I am and much less able than myself to brave such hardships as may be attendant upon jail life, she feels she must go to Rajkot. And before this is in print she might have gone there.1 But I want to take a detached view of the struggle. Sardar’s statement 2, reproduced elsewhere, is a legal document in the sense that it has not a superfluous word in it and contains nothing that cannot be supported by unimpeachable evidence most of which is based on written records which are attached to it as appendices. It furnishes evidence of a cold-blooded breach of a solemn covenant entered into between the Rajkot Ruler and his people.3 And the breach has been committed at the instance and bidding of the British Resident 4 who is directly linked with the Viceroy. To the covenant a British Dewan5 was party. His boast was that he represented British authority. He had expected to rule the Ruler. He was therefore no fool to fall into the Sardar’s trap. Therefore, the covenant was not an extortion from an imbecile ruler. The British Resident detested the Congress and the Sardar for the crime of saving the Thakore Saheb from bankruptcy and, probably, loss of his gadi. -

The Gita According to GANDHI

The Gita according to GANDHI The Gospel of Selfless Action OR The Gita according to GANDHI By: Mahadev Desai First Published: August 1946 Printed & Published by: Vivek Jitendrabhai Desai Navajivan Mudranalaya Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) www.mkgandhi.org Page 1 The Gita according to GANDHI Forward The following pages by Mahadev Desai are an ambitious project. It represents his unremitting labours during his prison life in 1933-'34. Every page is evidence of his scholarship and exhaustive study of all he could lay hands upon regarding the Bhagavad Gita, poetically called the Song Celestial by Sir Edwin Arnold. The immediate cause of this labour of love was my translation in Gujarati of the divine book as I understood it. In trying to give a translation of my meaning of the Gita, he found himself writing an original commentary on the Gita. The book might have been published during his lifetime, if I could have made time to go through the manuscript. I read some portions with him, but exigencies of my work had to interrupt the reading. Then followed the imprisonments of August 1942, and his sudden death within six days of our imprisonment. All of his immediate friends decided to give his reverent study of the Gita to the public. He had copies typed for his English friends who were impatient to see the commentary in print. And Pyarelal, who was collaborator with Mahadev Desai for many years, went through the whole manuscript and undertook to perform the difficult task of proof reading. Hence this publication. Frankly, I do not pretend to any scholarship. -

Rajaji's Role in Indian Freedom Struggle

JNROnline Journal Journal of Natural Remedies ISSN: 2320-3358 (e) Vol. 21, No. 3(S2),(2020) ISSN: 0972-5547(p) RAJAJI’S ROLE IN INDIAN FREEDOM STRUGGLE Dr. M. GnanaOslin Assistant Professor Department of History, D.G.Govt. Arts College for Women, Mayiladuthurai ABSTRACT Rajagopalachariar popularly known as Rajaji or C.R.Rajaji was born on 8th Dec 1878 at Thorappalli in Salem Dist. Rajaji was one among the selected band of leaders who participated in the freedom movement of India. His emergence at various stages of the freedom movement, his dedication to the national cause and his untiring struggle against the British rule earned him a significant place in the history of the freedom movement. His stature as a front-rank national leader is a tribute to his devoted service for the cause of the nation for almost four decades and his whole career was a record of self-confidence, courage, fearlessness and innovations based on Gandhian concepts.Rajaji was one man among all the lieutenants of Gandhiji who followed the Gandhian path of life in thought, word and action. He was a true follower of Gandhiji. Rajaji had fully devoted himself to the cause of the national movement from 1920 to 1937. He involved himself in Non Co –operation Movement, The constructive programme of the congress, The Khadar Movement, Anti- Untouchability Campaign,Vedarnayam Salt Satyagraha ,Individual Satyagraha and Temple Entry Movement. He was opposed and did not participate in the Quit India Movement of 1942. His individual spirit, service and sacrifice encouraged his followers. Rajaji represented fundamentally the highest type of the mind of India. -

Shahed Ahmed Power

GANDHI DEEP ECOLOGY: -4 Experiencing thg Nonhuman Environment Shahed Ahmed Power Ph. D. Thesis Environmental Resources Unit, University of Salford 1990 r Dedicated to all my friends and to the memory of Sugata Dasgupta (1926 - 1984) iii Contents Page List of Maps iii Acknowledgements iv Abbreviations vi Abstract viii Introduction 1 The psychological background 4 Chapter I: GANDHI: The Early Years 12 Chapter II: GANDHI: South Africa 27 Chapter III: GANDHI: India 1915 - 1931 59 Chapter IV: GANDHI: India 1931 - 1948 93 Chapter V: THOREAU: 1817 - 1862 120 Chapter VI: Background to Deep Ecology 153 John Muir (1838 - 1914) 154 Richard Jefferies (1848 - 1887) 168 Mary Austin (1868 - 1934) 172 Aldo Leopold (1886 - 1948) 174 Richard St. Barbe Baker (1889 - 1982) 177 Indigenous People: 178 (i) Amerindian 179 (ii) North-East India 184 Chapter VII: ARNE NAESS 191 Chapter VIII: Summary & Synthesis 201 Bibliography 211 Appendix 233 List of Maps: Map of Indian Subcontinent - between pages 58 and 59 Map of North-East India - between pages 184 and 185 iv Acknowledgements: Though he is not mentioned in the main body of the text, I have-been greatly influenced by the writings and life of the American religious writer Thomas Merton (1915 - 1968). Born in Prades, France, Thomas Merton grew up in France, England and the United States. In 1941 he entered the Trappist monastery, the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, Kentucky, where he is now buried, though he died in Bangkok. The later Merton especially was a guide to much of my reading in the 1970s. For many years now I have treasured a copy of Merton's own selection from the writings of Gandhi on Non-Violence (Gandhi, 1965), as well as a collection of his essays on peace (Merton, 1976). -

Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Volume 98

1. GIVE AND TAKE1 A Sindhi sufferer writes: At this critical time when thousands of our countrymen are leaving their ancestral homes and are pouring in from Sind, the Punjab and the N. W. F. P., I find that there is, in some sections of the Hindus, a provincial spirit. Those who are coming here suffered terribly and deserve all the warmth that the Hindus of the Indian Union can reasonably give. You have rightly called them dukhi,2 though they are commonly called sharanarthis. The problem is so great that no government can cope with it unless the people back the efforts with all their might. I am sorry to confess that some of the landlords have increased the rents of houses enormously and some are demanding pagri. May I request you to raise your voice against the provincial spirit and the pagri system specially at this time of terrible suffering? Though I sympathize with the writer, I cannot endorse his analysis. Nevertheless I am able to testify that there are rapacious landlords who are not ashamed to fatten themselves at the expense of the sufferers. But I know personally that there are others who, though they may not be able or willing to go as far as the writer or I may wish, do put themselves to inconvenience in order to lessen the suffering of the victims. The best way to lighten the burden is for the sufferers to learn how to profit by this unexpected blow. They should learn the art of humility which demands a rigorous self-searching rather than a search of others and consequent criticism, often harsh, oftener undeserved and only sometimes deserved. -

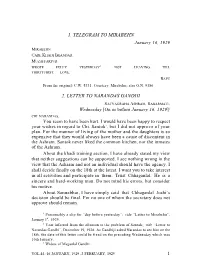

1. Telegram to Mirabehn 2. Letter to Narandas Gandhi

1. TELEGRAM TO MIRABEHN January 16, 1929 MIRABEHN CARE KHADI BHANDAR MUZAFFARPUR WROTE FULLY YESTERDAY1. NOT LEAVING TILL THIRTYFIRST. LOVE. BAPU From the original: C.W. 5331. Courtesy: Mirabehn; also G.N. 9386 2. LETTER TO NARANDAS GANDHI SATYAGRAHA ASHRAM, SABARMATI, Wednesday [On or before January 16, 1929]2 CHI. NARANDAS, You seem to have been hurt. I would have been happy to respect your wishes in regard to Chi. Santok3, but I did not approve of your plan. For the manner of living of the mother and the daughters is so expensive that they would always have been a cause of discontent in the Ashram. Santok never liked the common kitchen, nor the inmates of the Ashram. About the khadi training section, I have already stated my view that neither suggestions can be supported. I see nothing wrong in the view that the Ashram and not an individual should have the agency. I shall decide finally on the 18th at the latest. I want you to take interest in all activities and participate in them. Trust Chhaganlal. He is a sincere and hard-working man. Do not mind his errors, but consider his motive. About Sannabhai, I have simply said that Chhaganlal Joshi’s decision should be final. For no one of whom the secretary does not approve should remain. 1 Presumably a slip for “day before yesterday”; vide “Letter to Mirabehn”, January 14, 1929. 2 Year inferred from the allusion to the problem of Santok; vide “Letter to Narandas Gandhi”, December 19, 1928. As Gandhiji asked Narandas to see him on the 18th, the date of this letter could be fixed on the preceding Wednesday which was 16th January.