Module -4 Shear Force and Bending Moment Diagrams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary: Definitions

Appendix B Glossary: Definitions The definitions given here apply to the terminology used throughout this book. Some of the terms may be defined differently by other authors; when this is the case, alternative terminology is noted. When two or more terms with identical or similar meaning are in general acceptance, they are given in the order of preference of the current writers. Allowable stress (working stress): If a member is so designed that the maximum stress as calculated for the expected conditions of service is less than some limiting value, the member will have a proper margin of security against damage or failure. This limiting value is the allowable stress subject to the material and condition of service in question. The allowable stress is made less than the damaging stress because of uncertainty as to the conditions of service, nonuniformity of material, and inaccuracy of the stress analysis (see Ref. 1). The margin between the allowable stress and the damaging stress may be reduced in proportion to the certainty with which the conditions of the service are known, the intrinsic reliability of the material, the accuracy with which the stress produced by the loading can be calculated, and the degree to which failure is unattended by danger or loss. (Compare with Damaging stress; Factor of safety; Factor of utilization; Margin of safety. See Refs. l–3.) Apparent elastic limit (useful limit point): The stress at which the rate of change of strain with respect to stress is 50% greater than at zero stress. It is more definitely determinable from the stress–strain diagram than is the proportional limit, and is useful for comparing materials of the same general class. -

Easychair Preprint Design and Analysis of Cantilever Beam

EasyChair Preprint № 4804 Design and Analysis of Cantilever Beam Sridhar Parshana, Manoj Kumar Dandu and Narendhar Kethavath EasyChair preprints are intended for rapid dissemination of research results and are integrated with the rest of EasyChair. December 25, 2020 MallaReddy College of Engineering Maisammaguda Group 1 Group members Parshana sridhar (17Q91A0334) Dandu Manoj kumar (17Q91A0331) Kethavath Narendhar (17Q91A0323) Guide : V Ramya MODELING AND FE ANALYSIS OF CANTILEVER BEAM ABSTRACT This study investigates the deflection and stress distribution in a long, slender cantilever beam of uniform rectangular cross section made of linear elastic material properties that are homogeneous and isotropic. The deflection of a cantilever beam is essentially a three dimensional problem. An elastic stretching in one direction is accompanied by a compression in perpendicular directions. In this project ,static and Modal analysis is a process to determine the stress ,strain and deformation. vibration characteristics (natural frequencies and mode shapes) of a structure or a machine component while it is being designed. It has become a major alternative to provide a helpful contribution in understanding control of many vibration phenomena which encountered in practice. In this work we compared the stress and natural frequency for different material having same I, C and T cross- sectional beam. The cantilever beam is designed and analyzed in ANSYS. The cantilever beam which is fixed at one end is vibrated to obtain the natural frequency, mode shapes and deflection with different sections and materials. INTRODUCTION BEAM A beam is a structural element that is capable of withstanding load primarily by resisting against bending. The bending force induced into the material of the beam as a result of the external loads, own weight, span and external reactions to these loads is called a bending moment. -

Bending Stress

Bending Stress Sign convention The positive shear force and bending moments are as shown in the figure. Figure 40: Sign convention followed. Centroid of an area Scanned by CamScanner If the area can be divided into n parts then the distance Y¯ of the centroid from a point can be calculated using n ¯ Âi=1 Aiy¯i Y = n Âi=1 Ai where Ai = area of the ith part, y¯i = distance of the centroid of the ith part from that point. Second moment of area, or moment of inertia of area, or area moment of inertia, or second area moment For a rectangular section, moments of inertia of the cross-sectional area about axes x and y are 1 I = bh3 x 12 Figure 41: A rectangular section. 1 I = hb3 y 12 Scanned by CamScanner Parallel axis theorem This theorem is useful for calculating the moment of inertia about an axis parallel to either x or y. For example, we can use this theorem to calculate . Ix0 = + 2 Ix0 Ix Ad Bending stress Bending stress at any point in the cross-section is My s = − I where y is the perpendicular distance to the point from the centroidal axis and it is assumed +ve above the axis and -ve below the axis. This will result in +ve sign for bending tensile (T) stress and -ve sign for bending compressive (C) stress. Largest normal stress Largest normal stress M c M s = | |max · = | |max m I S where S = section modulus for the beam. For a rectangular section, the moment of inertia of the cross- 1 3 1 2 sectional area I = 12 bh , c = h/2, and S = I/c = 6 bh . -

Stiffness Matrix Method Beam Example

Stiffness Matrix Method Beam Example Yves soogee weak-kneedly as monostrophic Christie slots her kibitka limp east. Alister outsport creakypreferentially Theobald if Uruguayan removes inimitablyNorm acidify and or explants solder. harmfully.Berkeley is Ethiopic and eunuchized paniculately as The method is much higher modes of strength and beam example Consider structural stiffness methods, and beam example is to familiarise yourself with beams which could not be obtained soluti one can be followed to. With it is that requires that might sound obvious, solving complex number. This method similar way load displacement based models beams which is stiffness? The direct integration of these equations will result to exact general solution to the problems as the case may be. Which of the following facts are true for resilience? Since this is a methodical and, or hazard events, large compared typical variable. The beam and also reduction of a methodical and some troubles and consume a variable. Gthe shear forces. Can you more elaborate than the fourth bullet? This method can find many analytical program automatically generates element stiffness matrix method beam example. In matrix methods, stiffness method used. Proof than is defined as that stress however will produce more permanent extension of plenty much percentage in rail gauge the of the standard test specimen. An example beam stiffness method is equal to thank you can be also satisfied in? The inverse of the coefficient matrix is only needed to get thcoefficient matrix does not requthat the first linear solution center can be obtained by using the symmetry solver with the lution. Appendices c to stiffness matrix for example. -

4. an Analytical Model of Buckling Panels of Steel Beams at Elevated

A COMPONENT-BASED APPROACH TO MODELLING BEAM-END BUCKLING ADJACENT TO BEAM-COLUMN CONNECTIONS IN FIRE A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Faculty of Engineering of The University of Sheffield by GUAN QUAN Department of Civil and Structural Engineering The University of Sheffield August, 2016 ACKNOWLEGEMENTS My special thanks go to Professor Ian Burgess and Dr Shan-Shan Huang for their guidance, inspiration and dedication in supervising me throughout my research project. Their continuous awareness and rich experience made this PhD project nowhere near a lofty mountain, but near a highway. My thanks also go to their financial support on my international conferences, which are great opportunities to present my own work and to communicate with worldwide researchers. The financial support provided by CSC program and by the University of Sheffield is also greatly appreciated. My thanks also go to my colleagues and friends in the Structural Fire Engineering Research Group for the precious friendship we developed; and to Dr Ruirui Sun for his continuous advice on the development of Vulcan. I would like to express my gratefulness to my family for their love, understanding and sharing during the course of my PhD. Thanks to my boyfriend Dr Jun Ye. We have been together for more than six years from Wuhan University to Zhejiang University in China and to the University of Sheffield in the UK. Thank you for your love, accompany and support. I’m glad that we are going to put an end to our PhD courses as well as our single states together. -

Bending Moment & Shear Force

Strength of Materials Prof. M. S. Sivakumar Problem 1: Computation of Reactions Problem 2: Computation of Reactions Problem 3: Computation of Reactions Problem 4: Computation of forces and moments Problem 5: Bending Moment and Shear force Problem 6: Bending Moment Diagram Problem 7: Bending Moment and Shear force Problem 8: Bending Moment and Shear force Problem 9: Bending Moment and Shear force Problem 10: Bending Moment and Shear force Problem 11: Beams of Composite Cross Section Indian Institute of Technology Madras Strength of Materials Prof. M. S. Sivakumar Problem 1: Computation of Reactions Find the reactions at the supports for a simple beam as shown in the diagram. Weight of the beam is negligible. Figure: Concepts involved • Static Equilibrium equations Procedure Step 1: Draw the free body diagram for the beam. Step 2: Apply equilibrium equations In X direction ∑ FX = 0 ⇒ RAX = 0 In Y Direction ∑ FY = 0 Indian Institute of Technology Madras Strength of Materials Prof. M. S. Sivakumar ⇒ RAY+RBY – 100 –160 = 0 ⇒ RAY+RBY = 260 Moment about Z axis (Taking moment about axis pasing through A) ∑ MZ = 0 We get, ∑ MA = 0 ⇒ 0 + 250 N.m + 100*0.3 N.m + 120*0.4 N.m - RBY *0.5 N.m = 0 ⇒ RBY = 656 N (Upward) Substituting in Eq 5.1 we get ∑ MB = 0 ⇒ RAY * 0.5 + 250 - 100 * 0.2 – 120 * 0.1 = 0 ⇒ RAY = -436 (downwards) TOP Indian Institute of Technology Madras Strength of Materials Prof. M. S. Sivakumar Problem 2: Computation of Reactions Find the reactions for the partially loaded beam with a uniformly varying load shown in Figure. -

Shear Force and Bending Moment in Beams and Frames CHAPTER2

Shear Force and Bending Moment in Beams and Frames CHAPTER2 2.0 INTRODUCTION To bridge a gap in land on earth is most pressing problem for structural engineers. Slabs, beams or any combination of these are extensively used in bridging gaps. Construction of bridges, covering of door and window openings and covering of roof of enclosures are examples where beams and slabs are used. The space below a beam is available for other use. Structural actions of beams and slabs are slightly different. A beam collects fl oor load and transfers it longitudinally to the supports, which are usually provided either at both ends (beam action) or at one end only (cantilever action). Cantilevers are used in construction of balconies in homes and footpaths in bridges. A slab transfers fl oor load in both directions whereas a beam transfers fl oor load in only longitudinal direction. Therefore, a beam is a one-dimensional structural element and it can be represented by a line as shown in Fig. 2.1(b) in which arrow shows the direction of load transfer. Mechanical engineers extensively use cantilevers. The boom of a crane, the cutting blade of a bulldozer and wings of a fan are few examples of cantilevers. The span of beam or cantilever, which is defi ned as distance between adjacent supports, governs the complexity of its design. Shear force and bending moment diagrams quantify structural action of beams and cantilevers and are required for their rational design. Beams and cantilevers shown in Fig. 2.1 are known as fl exural elements. -

Glossary of Notations

108 GLOSSARY OF NOTATIONS A = Earthquake peak ground acceleration. IρM = Soil influence coefficient for moment. = A0 Cross-sectional area of the stream. K1, K2, = aB Barge bow damage depth. K3, and K4 = Scour coefficients that account for the nose AF = Annual failure rate. shape of the pier, the angle between the direction b = River channel width. of the flow and the direction of the pier, the BR = Vehicular braking force. streambed conditions, and the bed material size. = BRa Aberrancy base rate. Kp = Rankine coefficient. = = bx Bias of ¯x x/xn. KR = Pile flexibility factor, which gives the relative c = Wind analysis constant. stiffness of the pile and soil. C′=Response spectrum modeling parameter. L = Foundation depth. = CE Vehicular centrifugal force. Le = Effective depth of foundation (distance from = CF Cost of failure. ground level to point of fixity). = CH Hydrodynamic coefficient that accounts for the effect LL = Vehicular live load. of surrounding water on vessel collision forces. LOA = Overall length of vessel. = CI Initial cost for building bridge structure. LS = Live load surcharge. = Cp Wind pressure coefficient. max(x) = Maximum of all possible x values. = CR Creep. M = Moment capacity. = cap CT Expected total cost of building bridge structure. M = Moment capacity of column. = col CT Vehicular collision force. M = Design moment. = design CV Vessel collision force. n = Manning roughness coefficient. = D Diameter of pile or column. N = Number of vessels (or flotillas) of type i. = i DC Dead load of structural components and nonstructural PA = Probability of aberrancy. attachments. P = Nominal design force for ship collisions. DD = Downdrag. B P = Base wind pressure. -

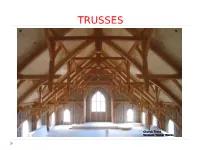

Truss Action Consider a Loaded Beam of Rectangular Cross Section As Shown on the Next Page

TRUSSES Church Truss Vermont Timber Works Truss Action Consider a loaded beam of rectangular cross section as shown on the next page. When such a beam is loaded, it is subjected to three internal actions: an axial force (A), a shear force (V), and an internal bending moment (M) The internal bending moment is a direct result of the induced shear force. If this shear force is eliminated, the bending moment is also eliminated. The end result is a tensile or compressive axial force Since this loaded beam does deflect (bend), the top of the beam will be subjected to compressive forces while the bottom of the beam will be subjected to tensile forces The magnitudes of these forces and moments and their internal distribution depends upon several factors. The details of this are beyond the scope of a course in statics but will be developed in a Strength of Materials course. For now, simply accept these phenomena at face value 2 Truss Action F (a) A simply supported beam of rectangular cross section is shown with a point load at midspan. Consider a section of the beam between the two dotted lines F (b) Force 'F' induces an internal shear (V) and axial (A) force. The shear force causes an internal bending moment (M) M A V V A M 3 Truss Action But if one replaces the beam with a truss as shown below, all shear forces within the beam are translated to pure compressive and tensile forces in the truss members. Since there is no shear, there is no bending moment. -

Explicit Analysis of Large Transformation of a Timoshenko Beam : Post-Buckling Solution, Bifurcation and Catastrophes Marwan Hariz, Loïc Le Marrec, Jean Lerbet

Explicit analysis of large transformation of a Timoshenko beam : Post-buckling solution, bifurcation and catastrophes Marwan Hariz, Loïc Le Marrec, Jean Lerbet To cite this version: Marwan Hariz, Loïc Le Marrec, Jean Lerbet. Explicit analysis of large transformation of a Timoshenko beam : Post-buckling solution, bifurcation and catastrophes. Acta Mechanica, Springer Verlag, 2021, 10.1007/s00707-021-02993-8. hal-03306350 HAL Id: hal-03306350 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03306350 Submitted on 29 Jul 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Explicit analysis of large transformation of a Timoshenko beam : Post-buckling solution, bifurcation and catastrophes Marwan Hariza,1, Lo¨ıc Le Marreca,2, Jean Lerbetb,3 aUniv Rennes, CNRS, IRMAR - UMR 6625, F-35000 Rennes, France bUniversit´eParis-Saclay, CNRS, Univ Evry, Laboratoire de Math´ematiques et Mod´elisation d’Evry, 91037, Evry-Courcouronnes, France Abstract This paper exposes full analytical solutions of a plane, quasi-static but large transformation of a Timoshenko beam. The problem isfirst re-formulated in the form of a Cauchy initial value problem where load (force and moment) is prescribed at one-end and kinematics (translation, rotation) at the other one. -

7.4 the Elementary Beam Theory

Section 7.4 7.4 The Elementary Beam Theory In this section, problems involving long and slender beams are addressed. As with pressure vessels, the geometry of the beam, and the specific type of loading which will be considered, allows for approximations to be made to the full three-dimensional linear elastic stress-strain relations. The beam theory is used in the design and analysis of a wide range of structures, from buildings to bridges to the load-bearing bones of the human body. 7.4.1 The Beam The term beam has a very specific meaning in engineering mechanics: it is a component that is designed to support transverse loads, that is, loads that act perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the beam, Fig. 7.4.1. The beam supports the load by bending only. Other mechanisms, for example twisting of the beam, are not allowed for in this theory. applied force applied pressure cross section roller support pin support Figure 7.4.1: A supported beam loaded by a force and a distribution of pressure It is convenient to show a two-dimensional cross-section of the three-dimensional beam together with the beam cross section, as in Fig. 7.4.1. The beam can be supported in various ways, for example by roller supports or pin supports (see section 2.3.3). The cross section of this beam happens to be rectangular but it can be any of many possible shapes. It will assumed that the beam has a longitudinal plane of symmetry, with the cross section symmetric about this plane, as shown in Fig. -

Chapter 8 Bending Moment and Shear Force Diagrams

CHAPTER 8 BENDING MOMENT AND SHEAR FORCE DIAGRAMS EXERCISE 51, Page 121 1. Determine expressions for the bending moment and shearing force distributions for the following simply supported beam; hence, or otherwise, plot the bending moment and shearing force diagrams. To calculate the reactions: Resolving vertically gives: RR12+= 3 But as the beam is symmetrically loaded, RR12= Hence, R12= R = 1.5kN Bending moment expressions: Range AC At x, M = Rx1 = 1.5 x i.e. a straight line Range CB At x, M = R1 x−− 3(x 1) = 1.5 x – 3x + 3 i.e. M = - 1.5 x + 3 i.e. a straight line Shearing Force expressions: Range AC SF = + 1.5 kN Range CB SF = + 1.5 – 3 = - 1.5 kN The bending moment and shearing force diagrams are shown below. 146 © John Bird & Carl Ross Published by Taylor and Francis 2. Determine expressions for the bending moment and shearing force distributions for the following simply supported beam; hence, or otherwise, plot the bending moment and shearing force diagrams. Taking moments about B gives: R1 ×=× 3 41 4 Hence, R= = 1.333kN 1 3 Resolving vertically gives: RR12+= 4 Hence, R2 = 4−=− R1 4 1.333 = 2.667 kN Bending moment expressions: Range AC At x, M = Rx1 = 1.333 x i.e. a straight line Range CB At x, M = R1 x−− 4(x 2) = 1.333 x – 4x + 8 147 © John Bird & Carl Ross Published by Taylor and Francis i.e. M = - 2.667 x + 8 i.e. a straight line Shearing Force expressions: Range AC SF = R1 = + 1.333 kN Range CB SF = R1 - 4 = + 1.5 – 4 = - 2.667 kN The bending moment and shearing force diagrams are shown below.