Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gazette of India

REGISTERED NO. D-222 The Gazette of India PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 10] NEW DELHI, SATURDAY, MAY 11, 1974 (VAISAKHA 21. 1896) Separate paging is given to this Part in order that it may be filed as a separate compilation. The undermentioned Gazettes of India Extraordinary were published up to the 28th February 1973:— Issue No. No. and Date Issued by Subject Copies of the Gazettes Extraordinary mentioned above will be supplied on indent to the Controller of Publi- cations, Civil Lines, Delhi. Indents should be submitted BO as to reach the Controller within ten days of the date of issue of these Gazettes. (501) 502 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA, MAY 11, 1974 (VAISAKHA 21, 1896) [PART I—SEC. 1 CONTENTS PART I—SECTION 1.—Notifications relating to Non- PAGE PART H—SECTION 3.—SUB. SEC. (ii).—Statutory PAGE Statutory Rules. Regulations Orders and Orders and Notifications issued by the Resolutions issued by the Ministries of the Ministries of the Government of India Government of India (other than the (other than the Ministry of Defence) and Ministry of Defence) and by the Supreme by the Central Authorities (other than the Court .. .. .. ., joi Administrations of Union Territories) .. 1289 PART I—SECTION 2.—Notifications regarding Ap- PART II—SECTION 4.—Statutory Rules and Orders pointments, Promotions, Leave etc. of notified by the Ministry of Defence .. 191 Government Officers issued by the Minis- PART III—SECTION 1.—Notifications issued by the tries of the Government of India (other Auditor General, Union Public Service than the Ministry of Defence) and by the Commission, Railway Administration, High Supreme Court . -

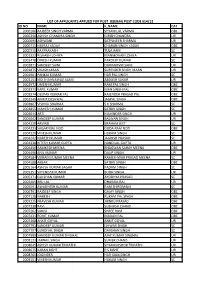

Id No Name F Name Cat 2000106 Rajbeer Singh Varma Shyam

LIST OF APPLICANTS APPLIED FOR POST JE(E&M) POST CODE 014/12 ID NO NAME F_NAME CAT 2000106 RAJBEER SINGH VARMA SHYAM LAL VARMA OBC 2000390 ASHISH CHANDRA SINGH GIRISH CHANDRA UR 2000695 ASHWANI SATYAVEER SHARMA UR 2000715 NEERAJ YADAV CHARAN SINGH YADAV OBC 2000716 RAJ PRAKASH TULA RAM SC 2001322 RISHABH LOHIYA MANMOHAN LOHIYA UR 2001478 DINESH KUMAR PARDEEP KUMAR SC 2001871 SANDEEP SAINI DAHRAMVIR SAINI UR 2001875 VIKASH MAAN SURENDER SINGH MAAN UR 2001901 PANKAJ KUMAR HAR PAL SINGH SC 2002153 MD SHAHNAWAZ ALAM ABDUSH SAKUR UR 2002972 UMESH KUMAR RAM PAL SINGH OBC 2002973 KAPIL KUMAR MAN SINGH PAL OBC 2002974 DEEPAK KUMAR PAL RAJENDER PRASAD PAL OBC 2003246 AMRIT DESHWAL JAGPAL SINGH OBC 2003807 VISHNU SHARMA S K SHARMA SC 2003855 MAHESH KUMAR SATBIR SINGH SC 2004014 ARTI MAHINDER SINGH UR 2004042 SANDEEP KUMAR BALWAN SINGH UR 2004220 ARVIND BRAHAM JEET SC 2004223 SAGAR MAL NOD GODA RAM NOD OBC 2004229 VINESH KUMAR HUKAM SINGH SC 2004242 NARESH KUMAR JAGDISH PRASAD SC 2004338 RITESH KUMAR GUPTA NAND LAL GUPTA UR 2004450 RAMKESH MEENA BHAGWAN SAHAY MEENA OBC 2004496 ANIL KUMAR DALIP SINGH UR 2004584 VIKRAM KUMAR MEENA RAMESHWAR PRASAD MEENA SC 2004588 AKBAR SATBIR SINGH OBC 2005164 ASHISH KUMAR SAGAR PADAM SINGH SC 2005351 SATENDAR KUMAR BUDH SINGH UR 2005371 GULSHAN KUMAR AYODHYA PRASAD SC 2005405 BRIJ LAL DHARAM RAJ UR 2005591 AWADHESH KUMAR RAM SHIROMANI SC 2006791 RAJDEEP SINGH GAJAY SINGH OBC 2007128 NARESH RUKAM PAL SINGH OBC 2007225 PRAVESH KUMAR JHINKU PRASAD OBC 2007238 RAVI SUBHASH CHAND OBC 2007262 SANJU SHREE RAM OBC 2007431 -

192Q =Le.=A 4=Ay Honour S Magha 1511S91 January 25,19710

OP. BRO TBQR ThOFilI 192Q =Le.=A_4=aY Honour s PRESS INFORMATION BUPEU(DEFENCE -WING) GOVERINENT OF INDIA GALlANTRY AND DISTINGUISED SVICE .ARDS FOR DEFENCE PERSONNEL Magha 15 11S91 New Delhi3------------ January 25,19710 The President has approvedTthe award of Param Vihisht Seva, Medal for distinguished service of the most exceptional order to nine officers. They are Lt.-Gen. Ajit Sirigh,ViCe- Lt.-Gen. Jagjit Singh Aurora, I -. Rawiley, Maj.-Gefl. Mm±ral Ni11cantaKrisbnan, Maj-Gefl. Naveen Chard Sagat Singh, Maj.-Gen. Thnrao Singh, Maj.-Gen. Mjhirsingh Gehisirigh Ajit Nath. Hazaii, Rear-Mmirai BanshThaj Singh and Air Vice Marshal The other awards announced are:- ATI VISHISIIT SEVA IvIEDAL Brig. Arunkumar Sridhar Vaidya, .Armoured Corps; Brig. Guddaj.cre Brig. Janki Dass Kap.or, R.V.C. Brig. Pritam Chandu Lal, Intelligence Corps; Brig. Ronald Jthur Regal O'Connor, Maratha Light Infantry; Brig. Risal Singh, Rajut.afla Rifles; Brig. Sukhwthit Singh, Artillery; Brig. Sudalayafldi Kolandavel-Us 1 Artillery; Brig. Shamsher Singh Pun, Armnoured Corps; Brig. Shabeg inz Grkha Rifles; Cmm4ore Darshan Chander Kapoor, I.N. Crnnidore Krpal Singh, I.N.; Comdore Raendra Tandon, I.N.; Air CQidOre Satpal Singh; Col. Iqbal SSin gh Artillery; Col.. Manohar Lal,Punab Col. AIG Monteiro2 Engineer Captain Balbir Dutt Law,I.N. s.rgen Captain DE Rosanio Faust Pint,I.N, Captain Lancelt Gomes, jTT IN.; flak.iri . :Y4 -2- Cai wamj Sriaharan, I-N-i Captain Mohan Sngh Grewal, T.N.; Captain M.R. eJrer,I.N.; Gp.-Capt. Igia Kar Singh Baksh±; Gp.-Capt, Bria Keith Stidston; G.-Capt, Lakshrnan Madhav Katre; Gp.-Capt. -

INFORMAT0N BUFU(D GOVER'nt of INDIA UTD DISTD Uise

fl T\TTTAT ü BFOCST TI MORPING WLG) PRESS INFORMAT0N BUFU(D GOVER'NT OF INDIA DEFANCE pERSONTEL SVICE .UURDS FOR GALLNTR UTD DISTD uISE i"tagha ,1291 New Delhi, - - - JanuarY 25 ;19?c The President has apprvedthe award of Param VjhjSht Seva ished seiCe of the most exPtiOfl order to Medal for j$tingU nine officers. They ares Jagjit Singh Aurora, Lt.-Gefl. Ajit Singh,.Vic TJt6-Gen nan Maj.-Gefl. Naveefl Chard RawilcY, Maj.-Gefl. l Ni1icanta A~Iir±ra gh GehiSifl Umrao Singh, Maj.-GOfl. jrsin Sagat Singh, Maj.-Gefl. Ajit Nath. Banshaj Singh and Air Vice rsha1 Hazai Rear_rnii'al The other awards annduncCd are- ATI VI3llISiT SEVA 11AL Brig. Guddalcre Vaidya, Armoured CorpSj Brig. Arunkumar Sridhar Brig. Janki DaSS Kap)Or, Brig. itam Chandu Lal ntelligencC CrpS Brig. Ronald xthUr Regal 01 Cnnr Maratha Light Infantry Brig. ja1Siflgh, Ra;utafla RifleS Artillery; Brig. Sudalayafldi Ko1afldaelU3 Brig. uthwflt Singh, Artillery; Brig. Shamsher Singh Pun, Armoured Corps; Brig, Sliabeg Bin Gorkha Rifles; Ccinmdore Darshan Chancier Iapoor, I.N. Crnmdore Krpal Singh3 I.N. Cornrdore Rajendra Tandon, I.N.; Air Cmmdore Manohar Lal,Punab Satpal Singh; Col. Iba1 Singh, Artillery; Col.. Captain Balbir Dutt Law,I.N. (l. AIG Monteiro, rmf.,ineer5, Surgeri Captain D RosariO Faust Pint:,I.N. Captain Lancelot Gomes, I.N.; Captain )giTr Snh -2- Cain Krishnaswami Sri(lylaran, I.N.-; Captain Mohan cinCh Gawal, Captain M.R. Gp-Capt. Iia Ka: S:Lngi Eacshi; y- G.-Cat. Brian Keith Stidstn; Gp.-Cant, Lakshmar Madhv Kat:re; Gp.-Caçt. Nittript Lal Ba..har; Gp.-Cspt. -

The Skirmish at Nathu La (1967), by V K Singh

scholar warrior The Skirmish at Nathu La (1967) VK SINGH Background Nathu La lies on the Old Silk Route between Tibet and India. In 1904, Major Francis Younghusband led a successful mission through Nathu La to capture Lhasa. This led to the setting up of trading posts at Gyantse and Gartok in Tibet, and gave control of the surrounding Chumbi Valley to the British. In 1947, Sikkim became an Indian protectorate. After China took control of Tibet in 1950, and suppressed a Tibetan uprising in 1959, refugees entered Sikkim through Nathu La. During the 1962 Sino-Indian War, Nathu La witnessed skirmishes between soldiers of the two countries. Shortly thereafter, the pass was sealed and closed for trade. Five years later, Nathu La was the scene of a ‘border skirmish’ between India and China, which resulted in heavy casualties to both sides. Significantly, it was the first and only instance when the Chinese got a ‘bloody nose’ from the Indians. In order to help Pakistan during the 1965 War, the Chinese served an ultimatum and asked India to withdraw its posts at Nathu La and Jelep La, which were then held by 17 and 27 Mountain Divisions respectively. Accordingly, orders were issued by Corps Headquarters (HQ) to both divisions to vacate Nathu La and Jelep La. As a result, 27 Mountain Division vacated Jelep La, which the Chinese promptly occupied. However, Major General Sagat Singh, GOC 17 Mountain Division, refused to vacate Nathu La, which was a Border Out Post (BOP), while the main defences were at Changgu. In the adjoining sector, manned 142 ä AUTUMN 2014 ä scholar warrior scholar warrior The Chinese got by 27 Mountain Division, Jelep La was also a BOP, a ‘bloody nose’ with the main defences located at Lungthu. -

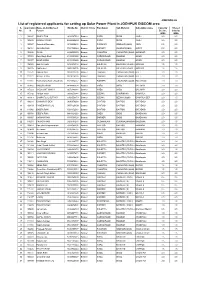

List of Registered Applicants for Setting up Solar Power Plant in JODHPUR DISCOM Area S

ANNEXURE-A2 List of registered applicants for setting up Solar Power Plant in JODHPUR DISCOM area S. application Name of Aurthorised Mobile No District Circle Panchayat Sub Division Substation name Capacity Offered No. id Person Declare Capcity (MW) (MW) 1 100827 SAWAI RAM 9414107518 Barmer SHEO SHEO AAKLI 2.0 0.5 2 108635 KAMALA SINGH 8094003699 Barmer SHEO SHEO AAKLI 2.0 2.0 3 105987 SohanLal Bhambhu 9799950691 Barmer SINDHARI SINDHARI(O&M) ADEL 0.5 0.5 4 106104 AAVADA DAN 7014759929 Barmer BARMER SAMDARI(O&M) AJEET 0.5 0.5 5 108626 SUJAL 8209005950 Barmer CHOHTAN CHOHATAN (O&M) ALAMSAR 2.0 2.0 6 107303 Raju Singh Bhati 8105621555 Barmer GADRA ROAD RAMSAR ASADI 2.0 2.0 7 108077 NAND KISOR 9166155229 Barmer GADRA ROAD RAMSAR ASADI 2.0 2.0 8 104025 jasa ram patel 9414914132 Barmer BALOTRA BALOTRA (RURAL) ASOTRA 1.5 1.5 9 106335 Radha devi 9680204305 Barmer BALOTRA BALOTRA (RURAL) ASOTRA 1.5 1.5 10 112272 Babulal Dosi 9829013598 Barmer DHANAU CHOHATAN (O&M) B.K.T. 2.0 1.0 11 112321 Mangi Lal Dosi 9829024324 Barmer DHANAU CHOHATAN (O&M) B.K.T. 2.0 1.0 12 112661 Rukhamana Ram Choudhary 9828984552 Barmer BARMER CHOHATAN (O&M) BACCHDAU 2.0 1.0 13 102465 BHOOR SINGH 9414492824 Barmer SHEO SHEO BALASAR 2.0 2.0 14 105323 HADAVANT SINGH 9672140081 Barmer SHEO SHEO BALASAR 2.0 2.0 15 105392 Hardan saran 9649250981 Barmer SEDWA DHORIMANA BAMARLA 2.0 2.0 16 103913 GANPAT LAL SUTHAR 6350556973 Barmer SEDWA SEDWA (O&M) BAMARLA DER 2.0 1.5 17 100210 BHANWARI DEVI 9636979638 Barmer BAYTOO BAYTOO BATADOO 2.0 2.0 18 100459 RAMESHWAR LAL 9587425100 Barmer -

Crnmdore Satpal Singh

z IBBi IE1 ORR 2RE 3 31FGRM ION BUREAiu(DEFNCE WING) GOIJERENT OF INDIA 'GALlANTRY MD DISTDGUISR) SVICE .AABDS FOR DEBECI PERSONNEL Magha ,191 1ew Delhi January 25 3197e The President has aprovedthe award of Param Vishisht Seva Medal for djstinuihed service of the most exceptional order to nine officers. They are Lt.-Gen, 1 Jagjit Singh Aurora, Lt.-Gen. Ajit Singh, Vice- &rn±ral Ni1kantaKriS11iflan, Maj.-Gefl. Naveen Chan.d Rawfley, Maj.-Gefl, Sagat Singh, Naj.-Geri. Umrao Singh, Maj-Gen. Mihirsingh Gehjsih Hazaili, Rear-dmira1 BanshThaj Singh and. Air Vice Marshal .kjit Nath. Tho other awards announced are:- ATI VISRISHT SEVA Vfl1AL Brig. Arunkuniar Sridhar Vaidya, Armoured Corps; Brig. Guddalre LaksbmInarasirri1la1 Sesagiri,E; Brig. Janki Dass Kapor, R.V.C.; Brig. Pritam Chandu Lal, Intelligence Ccrps; Brig. Ronald Arthur Regal O'Connor, Maratha Light Infantry; Brig, Risal Singh, Rajutana Rifles; Brig. Sukhwiit lngh, Artillery Brig, Sudalayaridl Kolandavelu, Artillery; Brig. Shamsher Singh Purl, Armoured Corps; Brig. Shabeg inY Grkha Rifles; Ccmncdore Darshan Chancier Kapoor, I.N.; Crnmdore Kfrpal Singh, I.N.; Ccmrrdore Rajendra Tandon, I.N.; Air Cnirndore Satpal Singh; Col. Iqbal Singh, Artillery; Col.. Manohar Lal,Punab; ol. AIG Monteiro Engineers; Captain Balbir Dutt Law,I.N.; Si.rgen Captain DE Rsario Faust Pint,I.N.; Capt.ain Lanc1ct Gbmes, .....i.; Caxtain igir1'r rgh Rarha-I.N.(Posthiimous); I Capt-ain Krighnaswami Sridharan, T.N.: Cauteir Mohan S.i.ngh Orewal, I.N.; Captain M.FL. Gp-Capt. Aia Far Sir:gh Bakshi; Gp.-Capt. Brian Keith Stidston; Gp..-Capt. Laks:nn.n 4adhav Katre; Gp, -Capt. -

Life Membership List from L01 to L 7091

L01 L08 H. M. PATEL I.C.S. RASIKLAL PHUNDILAL SHAH VALLABH VIDYANAGAR, VIA- ANAND, WEST JIMA PRAKASH ROAD, SHAHADA, DISTT- RAILWAY, GUJARAT DHULIA, MAHARASHTRA+ Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- ANAND - 0, Gujrat DHULIA - 0, Maharashtra L03 L09 PRAMUKHLAL M PATEL N.C. SHAH FRIENDS HOME, VEER NARIMAN ROAD, SHAHADA, WEST KHANDESH, MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI- 400001 Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- MUMBAI - 400001, Maharashtra WEST KHANDESH - 0, Maharashtra L05 L10 GIRDHAR LAL DAMODARDAS MADAN MOHAN MURAR KA REID ROAD, AHMADABAD, GUJARAT 7, LYONS RANGE P.O. BOX NO. 204 CALCUTA - 700001 Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- AHMADABAD - 0, Gujrat CALCUTTA - 0, West Bengal L06 L1000 LAVE GIRDHAR LAL RAMESH NARAIAN MATHUR REID ROAD, AHMADABAD, GUJARAT 45, SUBHAS NAGAR, GANDHI COLONY, MUZAFFAR NAGAR (UP) Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- AHMADABAD - 0, Gujrat MUZAFFAR NAGAR - 0, Uttar Pradesh L07 L1001 SHIBA PRASAD BANERJEE CHANAN SINGH RAMGARHIA 44, RAI BAHADUR SATISH, CHANDRA ROAD, PO- 1410/7, RAM NAGAR, LONI ROAD, SHAHDARA HOOGHLY BANDEL, WEST BENGAL- NEW DELHI-110032 Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- HOOGLY - 0, West Bengal SHAHDARA - 0, Delhi L1002 L1008 JUTA OBEROI GURDIP SINGH SAHI C/O MADDENS HOTEL DELHI 3035, SECTOR 28-D, CHANDIGARH Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- DELHI - 0, Delhi CHANDIGARH - 0, Chandigarh L1004 L1009 HABIB ULLAH KHAN BALRAJ SINGH GREWAL AT & P.O. BUTRAVA. DISTT. MUZAFFARNAGAR BXX-546, OPP. MUNNI LALA ATTA CHAKKI. (UP) GHUMAR MANDI, CIVIL LINES. LUDHIANA Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- MUZFFARNAGAR - 0, Uttar Pradesh LUDHIANA - 0, Punjab L1005 L101 ASGHAR ALI KHAN MADHUSUDAN C. PAREKH VILL & P.O. BUTRAVA DISTT. MUZAFFARNAGAR C/O. RAJNAGAR SPG & WVG. MILLS LTD (UP) Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- MUZAFFARNAGAR - 0, Uttar Pradesh AHMEDABAD - 0, Gujrat L1006 L1010 RAJ PAL SINGH MANN ASHOK NORONHA B-14, GEETANJALI ENCLAVE , MEHRAULI ROAD, E-1/42- AREA COLONY, S/O SHRI R.P. -

The Military Biography of Lt Gen Sagat Singh

GBUKOG6AHUIL » Book » A Talent for War: The Military Biography of Lt Gen Sagat Singh Get Doc A TALENT FOR WAR: THE MILITARY BIOGRAPHY OF LT GEN SAGAT SINGH Vij Books India Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, India, 2013. Hardcover. Book Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. Lt Gen Sagat Singh is unarguably the only military genius post independence India has produced. He commenced his military career through humble beginnings in the Bikaner State Forces with only a smattering knowledge of English. At the outbreak of World War 2 he was commissioned as an ofcer and served in the Middle East with his Battalion and on staff. By the time... Read PDF A Talent for War: The Military Biography of Lt Gen Sagat Singh Authored by Randhir Sinh Released at 2013 Filesize: 3.45 MB Reviews Basically no phrases to clarify. It really is writter in straightforward phrases rather than hard to understand. You will not sense monotony at at any moment of your own time (that's what catalogues are for concerning if you ask me). -- Doris Beier This pdf may be really worth a study, and much better than other. I could possibly comprehended every thing out of this composed e ebook. You will not sense monotony at anytime of your time (that's what catalogues are for regarding when you check with me). -- Elza Gusikowski The publication is great and fantastic. I actually have read through and i am sure that i am going to planning to go through yet again yet again down the road. I realized this pdf from my dad and i encouraged this publication to understand. -

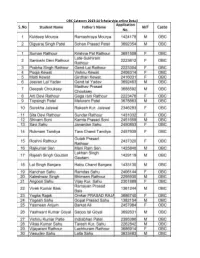

S.No Student Name Father's Name Application No. M/F Caste 1

OBC Category 2013-14 Scholarship online Detail Application Student Name Father's Name S.No No. M/F Caste 1 Kuldeep Mourya Ramashraya Mourya 1424178 M OBC 2 Digyaraj Singh Patel Sohan Prasad Patel 3692354 M OBC 1 Suman Rathour Krishna Pal Rathour 3691508 F OBC Late-Sukhiram 2 Santoshi Devi Rathour 2223612 F OBC Rathour 3 Prabha Singh Rathour Gend Lal Rathour 2223304 F OBC 4 Pooja Kewat Vishnu Kewat 2406314 F OBC 5 Malti Kewat Girdhari Kewat 2416031 F OBC 6 Jeevan Lal Yadav Gend lal Yadav 3692463 M OBC Madhav Prasad 7 Deepak Chouksey 3688592 M OBC Chouksey 8 Arti Devi Rathour Gaga ram Rathour 2223476 F OBC 9 Topsingh Patel Meluram Patel 3678863 M OBC 10 Surekha Jaiswal Rakesh Kur. Jaiswal 2346283 F OBC 11 Sita Devi Rathour Sundar Rathour 1431032 F OBC 12 Shivam Soni Kamta Prasad Soni 2451659 M OBC 13 Savi Sahu Janardan Sahu 2450853 F OBC 14 Rukmani Tandiya Tara Chand Tandiya 2457935 F OBC Gulab Prasad 15 Roshni Rathour 2437320 F OBC Rathour 16 Rajkumar Sen Mani Ram Sen 1425840 M OBC Lakhan Singh 17 Rajesh Singh Goutam 1429119 M OBC Gautam 18 Lal Singh Banjara Habu Chand Banjara 1433130 M OBC 19 Kanchan Sahu Ramdas Sahu 2406144 F OBC 20 Kaleshwar Singh Bhimsen Rathour 2295930 M OBC 21 Angoori Sahu Vijay Kur. Sahu 2301889 F OBC Ramayan Prasad 22 Vivek Kumar Bais 1361244 M OBC Bais 23 Yogita Rajak Omkar PRASAD RAJAK 3686740 F OBC 24 Yogesh Sahu Gopal Prasad Sahu 1382154 M OBC 25 Yasmeen Anjum Barkat Ali 2457984 F OBC 26 Yashwant Kumar Goyal Sarjoo lal Goyal 3692631 M OBC 27 Vishnu Kumar Patle Indrabhan Patel 2395390 M OBC 28 Vikas Kumar Sahu Taresh Kur. -

An Atlas of the 1971 India - Pakistan War: the Creation of Bangladesh by John H

! An Atlas of the 1971 India - Pakistan War: The Creation of Bangladesh by John H. Gill 1 2 Contents Preface .......................................................................................5 Conventions ...............................................................................6 List of maps ...............................................................................7 Acknowledgements ...................................................................9 1. The 1971 Overview ............................................................10 2. The Eastern Front .............................................................16 3. The Western Front ............................................................34 4. Air and Naval Operations ................................................61 5. Losses ..................................................................................65 6. Legacy .................................................................................66 Appendix: Orders of battle ......................................................68 Notes ........................................................................................91 Bibliography ............................................................................102 Index .........................................................................................109 About the Author ......................................................................112 3 4 Author’s Preface The 1971 War is the most recent major India-Pakistan -

Nursing Officer, Centenary Super Specialty Complex, SSH, BHU Post Code: 4479 Sl

. Date of Online Test (C.B.T.): 22nd September, 2019 Name of the Post: Nursing Officer, Centenary Super Specialty Complex, SSH, BHU Post Code: 4479 Sl. No. Form Number Name of the candidate Father's Name 1 4479019173 AABID AHMED ABDUL AZIZ 2 4479017994 AABID KHAN KAYAMKHANI AZAD KHAN KAYAMKHANI 3 4479019161 AABID MEER KHAN MUKHTAR MEER KHAN 4 4479011094 AACHUKI KHATEEK CHHOTU LAL KHATEEK 5 4479020893 AACHUKI DEVI JAT GULLA RAM JAT 6 4479017073 AADESH KUMAR PRAMOD KUMAR 7 4479008053 AADESH MEENA KIRODI LAL MEENA 8 4479014683 AADITY KUMAR RAI PARMATAMA RAI 9 4479016344 AAKANKSHA NARESH KUMAR 10 4479022951 AAKANKSHA YOGI RADHESHYAM YOGI 11 4479004104 AAKASH VISHWKARMA MADAN LAL VISHWKARMA 12 4479016295 AAMEEN SAEIN GULAB SAEIN 13 4479022729 AAMIR KHAN ZAKIR HUSAN 14 4479021727 AANCEE O V VARKEY O C 15 4479003291 AANESH KUMAR VISHNOI JAGMALA RAM VISHNOI 16 4479004530 AAPHTAB ALAM MD YUNUSH 17 4479020638 AARAM SINGH GURJAR DURGA SINGH GURJAR 18 4479006602 AARIF MOHAMMAD SHAREEF MOHAMMAD 19 4479017433 AARIF AHMAD QURESHI VAKIL AHMAD QURESHI 20 4479015027 AARTI JAGVEER SINGH 21 4479005196 AARTI KISHORI 22 4479008814 AARTI KUMARI UPENDRA SHARMA 23 4479021145 AARTI NAVIK RAGHUNANDAN NAVIK 24 4479016424 AARTI PATEL MAHENDRA KUMAR 25 4479006809 AARTI RASTOGI BABU LAL 26 4479002868 AARYA V T VIKRAMAN S 27 4479012567 AASHA CHOUDHARY SHISH RAM CHOUDHARY 28 4479010193 AASHEESH KUMAR MEENA SIYARAM MEENA 29 4479003328 AASHIMA CHANDER PAL 30 4479008263 AASHIQ KHAN AHSAN KHAN 31 4479014367 AASHISH VYAS MUKUT BIHARI VYAS 32 4479009582 AASHISH VYAS MUKUT