Re-Writing the Frontier Myth: Gender, Race, and Changing Conceptions of American Identity in Little House on the Prairie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premiere Props • Hollyw Ood a Uction Extra Vaganza VII • Sep Tember 1 5

Premiere Props • Hollywood Auction Extravaganza VII • September 15-16, 2012 • Hollywood Live Auctions Welcome to the Hollywood Live Auction Extravaganza weekend. We have assembled a vast collection of incredible movie props and costumes from Hollywood classics to contemporary favorites. From an exclusive Elvis Presley museum collection featured at the Mississippi Music Hall Of Fame, an amazing Harry Potter prop collection featuring Harry Potter’s training broom and Golden Snitch, to a entire Michael Jackson collection featuring his stage worn black shoes, fedoras and personally signed items. Plus costumes and props from Back To The Future, a life size custom Robby The Robot, Jim Carrey’s iconic mask from The Mask, plus hundreds of the most detailed props and costumes from the Underworld franchise! We are very excited to bring you over 1,000 items of some of the most rare and valuable memorabilia to add to your collection. Be sure to see the original WOPR computer from MGM’s War Games, a collection of Star Wars life size figures from Lucas Film and Master Replicas and custom designed costumes from Bette Midler, Kate Winslet, Lily Tomlin, and Billy Joel. If you are new to our live auction events and would like to participate, please register online at HollywoodLiveAuctions.com to watch and bid live. If you would prefer to be a phone bidder and be assisted by one of our staff members, please call us to register at (866) 761-7767. We hope you enjoy the Hollywood Live Auction Extravaganza V II live event and we look forward to seeing you on October 13-14 for Fangoria’s Annual Horror Movie Prop Live Auction. -

Lynn's 2020 Vision

ESSEX MEDIA GROUP PERSONS OF THE YEAR TO BE CELEBRATED TUESDAY. PAGE A4. FRIDAY, JANUARY 10, 2020 LYNN’S 2020 VISION BY GAYLA CAWLEY The City of Lynn’s 18 elected of cials were asked what his or her top priority is for the next two years, and how they plan to meet those goals. Their priorities included new schools, public safety, and development. Answers were edited for space. THOMAS M. MCGEE DARREN CYR BUZZY BARTON BRIAN FIELD BRIAN LAPIERRE HONG NET Mayor City Council President Council Vice President At-Large At-Large At-Large Ward 3 At-Large McGee said his pri- Field said he plans to LaPierre said his top Net said his top pri- ority is beginning to Cyr declined to des- Barton said his top continue working with priority was focused on ority is increasing di- implement the city’s ignate one of his many priority was to keep the colleagues on the City improving the quali- versity in City Hall 5-year capital improve- priorities as outweigh- city going in the right Council, the mayor and ty of education in the staff. ment plan, which in- the Lynn legislative city, in terms of making “I’ve been thinking ing the others in im- direction by trying to cludes $230.9 million delegation to address improvements to cur- of more diverse em- portance, but he did bring in more revenue. worth of capital proj- the needs the city has. rent school buildings ployment because I ects. speak at length about “Without revenue, we He said improving and constructing new see that we don’t have About 70 percent of his focus on develop- can’t do a lot of things,” public safety is his top schools. -

The Literary Apprenticeship of Laura Ingalls Wilder

Copyright © 1984 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. The Literary Apprenticeship of Laura Ingalls Wilder WILLIAM T. ANDERSON* Fifty years after the publication of Laura Ingalls Wilder's first book. Little House in the Big Woods (1932), that volume and eight succeeding volumes of the author's writings are American classics. The "Little House" books have been read, reread, trans- lated, adapted, and admired by multitudes world-wide. Wilder's books, which portray the frontier experience during the last great American expansionist era, "have given a notion of what pioneer life was like to far more Americans than ever heard of Frederick Jackson Turner."' Laura Ingalls Wilder's fame and the success of her books have been spiraling phenomenons in American publishing history. In I *The author wishes to acknowledge the many people who have contributed to the groundwork that resulted in this article. Among them are Roger Lea MacBride of Charlottesville. Va., whom I thank for years of friendship and favors—particu- larly the unlimited use of the once restricted Wilder papers; Mr. and Mrs. Aubrey Sherwood of De Smet, S.Dak., for loyal support and information exchange; Vera McCaskell and Vivian Glover of De SmeL, for lively teamwork; Dwight M. Miller and Nancy DeHamer of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, for research assistance; Dr. Ruth Alexander of South Dakota State University, for valuable sug- gestions and criticism; Alvilda Myre Sorenson, for encouragement and interest; and Mary Koltmansberger, for expert typing. 1. Charles Elliott, review of The First Four Years, by Laura Ingalls Wilder, in Time. -

Frontier Re-Imagined: the Mythic West in the Twentieth Century

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Frontier Re-Imagined: The yM thic West In The Twentieth Century Michael Craig Gibbs University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gibbs, M.(2018). Frontier Re-Imagined: The Mythic West In The Twentieth Century. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5009 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRONTIER RE-IMAGINED : THE MYTHIC WEST IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Michael Craig Gibbs Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina-Aiken, 1998 Master of Arts Winthrop University, 2003 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: David Cowart, Major Professor Brian Glavey, Committee Member Tara Powell, Committee Member Bradford Collins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Michael Craig Gibbs All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To my mother, Lisa Waller: thank you for believing in me. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following people. Without their support, I would not have completed this project. Professor Emeritus David Cowart served as my dissertation director for the last four years. He graciously agreed to continue working with me even after his retirement. -

William S. Dallam: an American Tourist in Revolutionary Paris

WILLIAM S. DALLAM: AN AMERICAN TOURIST IN REVOLUTIONARY PARIS Robert L, Dietle s the Spanish proverb says, "He, who would bring home this wealth of the Indies, must carry the wealth of the Indies with him,•so it is in traveling, a man must carry knowledge with him if he would bring home knowledge. Samuel Johnson I Though France is second only to Great Britain in its influence upon the formation of our politics and culture, Americans have always been strangely ambivalent about the French. Our admiration for French ideas and culture has somehow been tinged by suspicions that the French were unprincipled, even corrupt, or given to extremism. Late-eighteenth-century Franco-Amerlcan relations illustrate this ambivalence. Traditional American hostility to France moderated after 1763 when the Treaty of Paris ended the French and Indian War, removing the single enemy powerful enough to impede the colonists' westward migration. French diplomatic and military support for the American Revolution completed the transformation; in just fifteen years France had moved from enemy to ally. For the first time, American enthusiasm for French politics and culture knew no bounds. American taste for things French, however, did not last. By 1793 the radical turn of events in France's own revolution increasingly repelled conservative Americans and sparked serious controversy within Washington's administration. American reaction to the French Revolution eventually played a crucial role in the development of political parties in the United States, and the wars of I ROBERT L. DIETLE, P•.D., teaches history at Western Kentucky University at Bowling Green, Kentucky. -

Portrayals of Stuttering in Film, Television, and Comic Books

The Visualization of the Twisted Tongue: Portrayals of Stuttering in Film, Television, and Comic Books JEFFREY K. JOHNSON HERE IS A WELL-ESTABLISHED TRADITION WITHIN THE ENTERTAINMENT and publishing industries of depicting mentally and physically challenged characters. While many of the early renderings were sideshowesque amusements or one-dimensional melodramas, numerous contemporary works have utilized characters with disabilities in well- rounded and nonstereotypical ways. Although it would appear that many in society have begun to demand more realistic portrayals of characters with physical and mental challenges, one impediment that is still often typified by coarse caricatures is that of stuttering. The speech impediment labeled stuttering is often used as a crude formulaic storytelling device that adheres to basic misconceptions about the condition. Stuttering is frequently used as visual shorthand to communicate humor, nervousness, weakness, or unheroic/villainous characters. Because almost all the monographs written about the por- trayals of disabilities in film and television fail to mention stuttering, the purpose of this article is to examine the basic categorical formulas used in depicting stuttering in the mainstream popular culture areas of film, television, and comic books.' Though the subject may seem minor or unimportant, it does in fact provide an outlet to observe the relationship between a physical condition and the popular conception of the mental and personality traits that accompany it. One widely accepted definition of stuttering is, "the interruption of the flow of speech by hesitations, prolongation of sounds and blockages sufficient to cause anxiety and impair verbal communication" (Carlisle 4). The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 41, No. -

49Th USA Film Festival Schedule of Events

HIGH FASHION HIGH FINANCE 49th Annual H I G H L I F E USA Film Festival April 24-28, 2019 Angelika Film Center Dallas Sienna Miller in American Woman “A R O L L E R C O A S T E R O F FABULOUSNESS AND FOLLY ” FROM THE DIRECTOR OF DIOR AND I H AL STON A F I L M B Y FRÉDERIC TCHENG prODUCeD THE ORCHARD CNN FILMS DOGWOOF TDOG preSeNT a FILM by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG IN aSSOCIaTION WITH pOSSIbILITy eNTerTaINMeNT SHarp HOUSe GLOSS “HaLSTON” by rOLaND baLLeSTer CO- DIreCTOr OF eDITeD MUSIC OrIGINaL SCrIpTeD prODUCerS STepHaNIe LeVy paUL DaLLaS prODUCer MICHaeL praLL pHOTOGrapHy CHrIS W. JOHNSON by ÈLIa GaSULL baLaDa FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG SUperVISOr TraCy MCKNIGHT MUSIC by STaNLey CLarKe CINeMaTOGrapHy by aarON KOVaLCHIK exeCUTIVe prODUCerS aMy eNTeLIS COUrTNey SexTON aNNa GODaS OLI HarbOTTLe LeSLey FrOWICK IaN SHarp rebeCCa JOerIN-SHarp eMMa DUTTON LaWreNCe beNeNSON eLySe beNeNSON DOUGLaS SCHWaLbe LOUIS a. MarTaraNO CO-exeCUTIVe WrITTeN, prODUCeD prODUCerS ELSA PERETTI HARVEY REESE MAGNUS ANDERSSON RAJA SETHURAMAN FeaTUrING TaVI GeVINSON aND DIreCTeD by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG Fest Tix On@HALSTONFILM WWW.HALSTON.SaleFILM 4 /10 IMAGE © STAN SHAFFER Udo Kier The White Crow Ed Asner: Constance Towers in The Naked Kiss Constance Towers On Stage and Off Timothy Busfield Melissa Gilbert Jeff Daniels in Guest Artist Bryn Vale and Taylor Schilling in Family Denise Crosby Laura Steinel Traci Lords Frédéric Tcheng Ed Zwick Stephen Tobolowsky Bryn Vale Chris Roe Foster Wilson Kurt Jacobsen Josh Zuckerman Cheryl Allison Eli Powers Olicer Muñoz Wendy Davis in Christina Beck -

Indian Warfare, Household Competency, and the Settlement of the Western Virginia Frontier, 1749 to 1794

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2007 Indian warfare, household competency, and the settlement of the western Virginia frontier, 1749 to 1794 John M. Boback West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Boback, John M., "Indian warfare, household competency, and the settlement of the western Virginia frontier, 1749 to 1794" (2007). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 2566. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/2566 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Indian Warfare, Household Competency, and the Settlement of the Western Virginia Frontier, 1749 to 1794 John M. Boback Dissertation submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor -

Social and Economic Sustainability Report

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest November 2008 Social and Economic Sustainability Report Coronado NF Social and Economic Sustainability Report Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................1 Historical Context........................................................................................................................................4 Demographic and Economic Conditions ...................................................................................................6 Demographic Patterns and Trends.............................................................................................................6 Total Persons.........................................................................................................................................7 Population Age......................................................................................................................................7 Racial / Ethnic Composition..................................................................................................................8 Educational Attainment.......................................................................................................................10 Housing ...............................................................................................................................................12 -

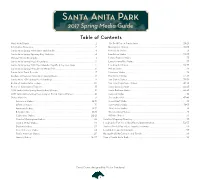

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

Michael Landon-Murray, Ph.D

Michael Landon-Murray, Ph.D. University of Colorado, Colorado Springs – School of Public Affairs 1420 Austin Bluffs Pkwy Colorado Springs, CO 80918 (719) 255-4185 – [email protected] Academic Positions Assistant Professor, University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, School of Public Affairs, 2015 - present Visiting Assistant Professor, University of Texas at El Paso, National Security Studies Institute, 2014 - 2015 Adjunct Instructor, University at Albany, Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy, 2014 Education PhD, Public Administration and Policy, University at Albany, SUNY 2013 Honors: Doctoral Research Assistantship, 2007 - 2009 Dissertation: Essays on Academic Intelligence and Security Education Master of Public and International Affairs, University of Pittsburgh 2005 Honors: Graduate Tuition Fellowship, 2004 - 2005 Field: Security and Intelligence Studies BA, Political Science, University at Buffalo, SUNY 2003 Publications Books Coulthart, Stephen, Michael Landon-Murray and Damien Van Puyvelde (eds.). 2019. Researching National Security Intelligence: Multidisciplinary Approaches. Georgetown University Press. Refereed Journals Landon-Murray, Michael and Stephen Coulthart. 2020. Intelligence Studies Programs as US Public Policy: A Survey of IC CAE Grant Recipients. Intelligence and National Security, 35(2), 269-282. Landon-Murray, Michael, Edin Mujkic and Brian Nussbaum. 2019. Disinformation in Contemporary US Foreign Policy: Impacts and Ethics in an Era of Fake News, Social Media, and Artificial Intelligence. Public Integrity, 21(5), 512-522. Landon-Murray, Michael. 2017. US Intelligence Studies Programs and Educators in the “Post-Truth” Era. International Journal of Intelligence, Security, and Public Affairs, 19(3), 197-213. Landon-Murray, Michael. 2017. Putting a Little More “Time” Into Strategic Intelligence Analysis. International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 30(4), 785-809. -

Imagination, Mythology, Artistry and Play in Laura Ingalls Wilder’S Little House

PLAYING PIONEER: IMAGINATION, MYTHOLOGY, ARTISTRY AND PLAY IN LAURA INGALLS WILDER’S LITTLE HOUSE By ANNA LOCKHART A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in English Written under the direction of Holly Blackford And approved by _____________________________ Dr. Holly Blackford _____________________________ Dr. Carol Singley Camden, New Jersey January 2017 THESIS ABSTRACT “Playing Pioneer: Imagination, Mythology, Artistry and Play in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House” By ANNA LOCKHART Thesis Director: Holly Blackford Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House series is a fictionalized account of Wilder’s childhood growing up in a family settling the American frontier in the late nineteenth- century. As much as the series is about childhood and the idyllic space of the blank, uncultivated frontier, it is about a girl growing into a woman, replacing childhood play and dreams with an occupation, sense of meaning, and location as an adult, woman, citizen, and artist. In this essay, I explore the depictions of play in the series as their various iterations show Laura’s departure from childhood and mirror the cultivation and development of the frontier itself. In my reading, I locate four distinct elements of play to answer these questions: Laura’s interactions and negotiations with various doll figures; her use of play as a tool to explore and bend boundaries and gender prescriptions; play as an industrious act intermingled with work; and her play with words, which allows her to transition out of childhood into a meaningful role as artist, playing an important role in the mythologizing and narration of the American frontier story.