CHAPITRE 2 Les Zoonoses Dues À Des Trématodes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation and Diversification of the Transcriptomes of Adult Paragonimus Westermani and P

Li et al. Parasites & Vectors (2016) 9:497 DOI 10.1186/s13071-016-1785-x RESEARCH Open Access Conservation and diversification of the transcriptomes of adult Paragonimus westermani and P. skrjabini Ben-wen Li1†, Samantha N. McNulty2†, Bruce A. Rosa2, Rahul Tyagi2, Qing Ren Zeng3, Kong-zhen Gu3, Gary J. Weil1 and Makedonka Mitreva1,2* Abstract Background: Paragonimiasis is an important and widespread neglected tropical disease. Fifteen Paragonimus species are human pathogens, but two of these, Paragonimus westermani and P. skrjabini, are responsible for the bulk of human disease. Despite their medical and economic significance, there is limited information on the gene content and expression of Paragonimus lung flukes. Results: The transcriptomes of adult P. westermani and P. skrjabini were studied with deep sequencing technology. Approximately 30 million reads per species were assembled into 21,586 and 25,825 unigenes for P. westermani and P. skrjabini, respectively. Many unigenes showed homology with sequences from other food-borne trematodes, but 1,217 high-confidence Paragonimus-specific unigenes were identified. Analyses indicated that both species have the potential for aerobic and anaerobic metabolism but not de novo fatty acid biosynthesis and that they may interact with host signaling pathways. Some 12,432 P. westermani and P. skrjabini unigenes showed a clear correspondence in bi-directional sequence similarity matches. The expression of shared unigenes was mostly well correlated, but differentially expressed unigenes were identified and shown to be enriched for functions related to proteolysis for P. westermani and microtubule based motility for P. skrjabini. Conclusions: The assembled transcriptomes of P. westermani and P. -

Vet February 2017.Indd 85 30/01/2017 09:32 SMALL ANIMAL I CONTINUING EDUCATION

CONTINUING EDUCATION I SMALL ANIMAL Trematodes in farm and companion animals The comparative aspects of parasitic trematodes of companion animals, ruminants and humans is presented by Maggie Fisher BVetMed CBiol MRCVS FRSB, managing director and Peter Holdsworth AO Bsc (Hon) PhD FRSB FAICD, senior manager, Ridgeway Research Ltd, Park Farm Building, Gloucestershire, UK Trematodes are almost all hermaphrodite (schistosomes KEY SPECIES being the exception) flat worms (flukes) which have a two or A number of trematode species are potential parasites of more host life cycle, with snails featuring consistently as an dogs and cats. The whole list of potential infections is long intermediate host. and so some representative examples are shown in Table Dogs and cats residing in Europe, including the UK and 1. A more extensive list of species found globally in dogs Ireland, are far less likely to acquire trematode or fluke and cats has been compiled by Muller (2000). Dogs and cats infections, which means that veterinary surgeons are likely are relatively resistant to F hepatica, so despite increased to be unconfident when they are presented with clinical abundance of infection in ruminants, there has not been a cases of fluke in dogs or cats. Such infections are likely to be noticeable increase of infection in cats or dogs. associated with a history of overseas travel. In ruminants, the most important species in Europe are the In contrast, the importance of the liver fluke, Fasciola liver fluke, F hepatica and the rumen fluke, Calicophoron hepatica to grazing ruminants is evident from the range daubneyi (see Figure 1). -

Worms, Germs, and Other Symbionts from the Northern Gulf of Mexico CRCDU7M COPY Sea Grant Depositor

h ' '' f MASGC-B-78-001 c. 3 A MARINE MALADIES? Worms, Germs, and Other Symbionts From the Northern Gulf of Mexico CRCDU7M COPY Sea Grant Depositor NATIONAL SEA GRANT DEPOSITORY \ PELL LIBRARY BUILDING URI NA8RAGANSETT BAY CAMPUS % NARRAGANSETT. Rl 02882 Robin M. Overstreet r ii MISSISSIPPI—ALABAMA SEA GRANT CONSORTIUM MASGP—78—021 MARINE MALADIES? Worms, Germs, and Other Symbionts From the Northern Gulf of Mexico by Robin M. Overstreet Gulf Coast Research Laboratory Ocean Springs, Mississippi 39564 This study was conducted in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA, Office of Sea Grant, under Grant No. 04-7-158-44017 and National Marine Fisheries Service, under PL 88-309, Project No. 2-262-R. TheMississippi-AlabamaSea Grant Consortium furnish ed all of the publication costs. The U.S. Government is authorized to produceand distribute reprints for governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation that may appear hereon. Copyright© 1978by Mississippi-Alabama Sea Gram Consortium and R.M. Overstrect All rights reserved. No pari of this book may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the author. Primed by Blossman Printing, Inc.. Ocean Springs, Mississippi CONTENTS PREFACE 1 INTRODUCTION TO SYMBIOSIS 2 INVERTEBRATES AS HOSTS 5 THE AMERICAN OYSTER 5 Public Health Aspects 6 Dcrmo 7 Other Symbionts and Diseases 8 Shell-Burrowing Symbionts II Fouling Organisms and Predators 13 THE BLUE CRAB 15 Protozoans and Microbes 15 Mclazoans and their I lypeiparasites 18 Misiellaneous Microbes and Protozoans 25 PENAEID -

Paragonimus Spp

GLOBAL WATER PATHOGEN PROJECT PART THREE. SPECIFIC EXCRETED PATHOGENS: ENVIRONMENTAL AND EPIDEMIOLOGY ASPECTS PARAGONIMUS SPP. Jong-Yil Chai Seoul National University College of Medicine Institute of Parasitic Diseases Korea Association of Health Promotion Seoul, South Korea Bong-Kwang Jung Institute of Parasitic Diseases Korea Association of Health Promotion Seoul, South Korea Copyright: This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/openaccess/terms-use-ccbysa-en). Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Citation: Chai, J.Y. and Jung, B.K. 2018. Paragonimus spp. In: J.B. Rose and B. Jiménez-Cisneros, (eds) Global Water Pathogen Project. http://www.waterpathogens.org (Robertson, L (eds) Part 4 Helminths) http://www.waterpathogens.org/book/paragonimus Michigan State University, E. Lansing, MI, UNESCO. https://doi.org/10.14321/waterpathogens.46 Acknowledgements: K.R.L. Young, Project Design editor; Website Design: Agroknow (http://www.agroknow.com) Last published: August 1, 2018 Paragonimus spp. -

Copyrighted Material

BLBS078-CF_A01 BLBS078-Tilley July 23, 2011 2:42 2 Blackwell’s Five-Minute Veterinary Consult A Abortion, Spontaneous (Early Pregnancy Loss)—Cats r r loss, discovery of fetal material, behavior Urethral obstruction Intestinal foreign r change, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea. body, pancreatitis, peritonitis Trauma r BASICS Physical Examination Findings Impending parturition or dystocia Purulent, mucoid, watery, or sanguinous CBC/BIOCHEMISTRY/URINALYSIS DEFINITION r r r vaginal discharge; dehydration, fever, May be normal. Inflammatory leukogram Spontaneous abortion—natural expulsion abdominal straining, abdominal discomfort. or stress leukogram depending on systemic r of a fetus or fetuses prior to the point at which CAUSES disease response. Hemoconcentration and they can sustain life outside the uterus. r Infectious azotemia with dehydration. Early pregnancy loss—generalized term for r OTHER LABORATORY TESTS any loss of conceptus including early Bacterial—Salmonella spp., Chlamydia, Brucella; organisms implicated in causing Infectious Causes embryonic death and resorption. r PATHOPHYSIOLOGY abortion via ascending infection include Cytology and bacterial culture of vaginal r Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus spp., discharge, fetus, fetal membranes, or uterine Infectious causes result in pregnancy loss by Streptococcus spp., Pasteurella spp., Klebsiella contents (aerobic, anaerobic, and r directly affecting the embryo, fetus, or fetal spp., Pseudomonas spp., Salmonella spp., mycoplasma). FeLV—test for antigens in membranes, or indirectly by creating Mycoplasma spp., and Ureaplasma spp. r r queens using ELISA or IFA. FHV-1—IFA debilitating systemic disease in the queen. Protozoal—Toxoplasma gondii— r r or PCR from corneal or conjunctival swabs, Non-infectious causes of pregnancy loss uncommon. Viral—FHV-1; FIV; FIPV; viral isolation from conjunctival, nasal, or r result from any factor other than infection FeLV;FPLV—virusesarethemostreported pharyngeal swabs. -

By Imperial Colleges London.. S, W, 7, October., 1954

ýl I STUDIES ON THE LIFE-HISTORY AND ECOLOGY . OF TREIMTODES OF THE GENUS RENICOLA COHN., 1904- Thesis submitted for the Degree Of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London by Christopher Amyas Wrightv B. Sc, Imperial Colleges London.. S, W, 7, October., 1954. ST COPY AVAILA L Variable print quality Abstract Trenatodes of the genus Renicola from British, birds are described and evidence to show the relationship between these flukes and the "Rhodonotopa" group of cercariae is prosented. The fooding-habits of all of the SPOcies of birds recorded as hosts for Renicola in Western Europe. aro analyzed to give an indication of the probable second intermediate host in the cycle. The ecology of Turritella comunis is discussed and reasons for the relation between infection with sporocysts of the "Rhodometopa" Broup and the size of the snails are suggested. Attempts to infect Turritella connunis with eggs from Renicola sp. are described and the results discussed. The development of the sporocystqof the "Rhodometopat' group of corcariae within the interlobular spaces of the gonad of Turritella communis is described. A novi interpretation of the structure of the sporocyst body- wall is presented. The appearance of a second daughter generation of sporocysts is described. The Sporocysts Historical An examination of some of the literaturo on this stage in the development of trematodos reveals a con- siderable variance of opinion on the structure of sporocysts and the function of various organs and cells found in them. This is possibly due to the fact that most general works refer only to the mother sporoeyst and go into considerably more detail on the structure of rediae than of daughter sporocYsts. -

Genus : Paragonimus

Genus : Paragonimus Instructor: Dr R. K. Sharma Assistant professor Department of Veterinary Parasitology Bihar Veterinary College, Patna. Paragonomus : Morphology . Paragonimus vary in size. The adult stage might attain a length up to 15-8 mm. The adult flatworm has an oval shape body with spines covering its thick tegument. Both the oral sucker and acetabulum are round and muscular. The acetabulum is slightly bigger than the oral sucker. Ovaries are located behind the acetabulum and posterior to the ovary are the testes. The seminal receptacle, the uterus and its metra term, the thick- walled terminal part, lie between the acetabulum and the ovary. SOURCE- GOOGLE Paragonimus : Parts of the body Dr.R.K.Sharma Paragonomus : Life cycle . Eggs are excreted in sputum or stool of infected people. In the environment, the eggs develop, hatch into an immature form e.g miracidia, which are ingested by snails. Inside the snail, the miracidia go through several stages to develop into cercariae. which can swim. The cercariae infect crabs or crayfish and form cysts called metacercariae. People are infected when they swallow cysts in raw, undercooked, or pickled freshwater crabs or crayfish. In the intestine, the larvae leave the cyst. The larvae penetrate the wall of the intestine, pass through the diaphragm, and invade the lungs. Where they develop into adults and produce eggs. These eggs are passed in sputum that is coughed up and spit out or swallowed and passed in stool. SOURCE- GOOGLE Paragonimus kellicotti : Life cycle Dr.R.K.Sharma SOURCE- GOOGLE Paragonimus westermani : Life cycle Dr.R.K.Sharma Paragonomus : Pathogenesis . -

Differing Effects of Standard and Harsh Nucleic Acid Extraction Procedures on Diagnostic Helminth Real-Time Pcrs Applied to Human Stool Samples

pathogens Article Differing Effects of Standard and Harsh Nucleic Acid Extraction Procedures on Diagnostic Helminth Real-Time PCRs Applied to Human Stool Samples Tanja Hoffmann 1, Andreas Hahn 2 , Jaco J. Verweij 3 ,Gérard Leboulle 4, Olfert Landt 4, Christina Strube 5 , Simone Kann 6, Denise Dekker 7 , Jürgen May 7 , Hagen Frickmann 1,2,† and Ulrike Loderstädt 8,*,† 1 Department of Microbiology and Hospital Hygiene, Bundeswehr Hospital Hamburg, 20359 Hamburg, Germany; [email protected] (T.H.); [email protected] or [email protected] (H.F.) 2 Institute for Medical Microbiology, Virology and Hygiene, University Medicine Rostock, 18057 Rostock, Germany; [email protected] 3 Laboratory for Medical Microbiology and Immunology, Elisabeth Tweesteden Hospital, 5042 AD Tilburg, The Netherlands; [email protected] 4 TIB MOLBIOL, 12103 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] (G.L.); [email protected] (O.L.) 5 Institute for Parasitology, Centre for Infection Medicine, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, 30559 Hannover, Germany; [email protected] 6 Medical Mission Institute, 97074 Würzburg, Germany; [email protected] 7 Infectious Disease Epidemiology Department, Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine Hamburg, 20359 Hamburg, Germany; [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (J.M.) Citation: Hoffmann, T.; Hahn, A.; 8 Department of Hospital Hygiene & Infectious Diseases, University Medicine Göttingen, Verweij, J.J.; Leboulle, G.; Landt, O.; 37075 Göttingen, Germany Strube, C.; Kann, S.; Dekker, D.; * Correspondence: [email protected] May, J.; Frickmann, H.; et al. Differing † Hagen Frickmann and Ulrike Loderstädt contributed equally to this work. Effects of Standard and Harsh Nucleic Acid Extraction Procedures Abstract: This study aimed to assess standard and harsher nucleic acid extraction schemes for on Diagnostic Helminth Real-Time diagnostic helminth real-time PCR approaches from stool samples. -

Classification and Nomenclature of Human Parasites Lynne S

C H A P T E R 2 0 8 Classification and Nomenclature of Human Parasites Lynne S. Garcia Although common names frequently are used to describe morphologic forms according to age, host, or nutrition, parasitic organisms, these names may represent different which often results in several names being given to the parasites in different parts of the world. To eliminate same organism. An additional problem involves alterna- these problems, a binomial system of nomenclature in tion of parasitic and free-living phases in the life cycle. which the scientific name consists of the genus and These organisms may be very different and difficult to species is used.1-3,8,12,14,17 These names generally are of recognize as belonging to the same species. Despite these Greek or Latin origin. In certain publications, the scien- difficulties, newer, more sophisticated molecular methods tific name often is followed by the name of the individual of grouping organisms often have confirmed taxonomic who originally named the parasite. The date of naming conclusions reached hundreds of years earlier by experi- also may be provided. If the name of the individual is in enced taxonomists. parentheses, it means that the person used a generic name As investigations continue in parasitic genetics, immu- no longer considered to be correct. nology, and biochemistry, the species designation will be On the basis of life histories and morphologic charac- defined more clearly. Originally, these species designa- teristics, systems of classification have been developed to tions were determined primarily by morphologic dif- indicate the relationship among the various parasite ferences, resulting in a phenotypic approach. -

Final Exam Parasitology

Fall 2018 VMP 930 Final Exam Parasitology Name:_____________________________ VMP 930 -- Final Exam (100 questions @ 2 points each = 200 points total) Protozoa (60 points) Nematodes (80 points) Arthropods (30 points) Platyhelminthes (30 points) Protozoa (60 points) Multiple Choice (There is one best answer for each question.) 1. A 5-year-old gelding presents with ataxia and incoordination in all four limbs. A CSF tap reveals antibodies to Sarcocystis neurona. How did the horse most likely acquire this infection? A. ingestion of sarcocysts in the muscle tissue of an infected opossum B. accidental ingestion of caddisflies from the pasture creek C. transmission of sporozoites via the bite of a tabanid fly D. ingestion of sporocysts from opossum feces in contaminated feed or water E. direct contact or interaction with an infected horse 2. A woman owns 3 cats and has just found out she is pregnant. Her doctor advises her to consult her veterinarian to determine her risk of parasite- associated complications. What should you do? A. Request a stool sample from both the cats and the woman. And do a fecal exam to try to find Toxoplasma gondii oocysts. B. Recommend serological testing for only the cats for Toxoplasma gondii. C. Recommend serological testing against Toxoplasma gondii for the cats for and recommend she ask her doctor that she also be serologically tested for Toxoplasma gondii. 3. Which feline protozoan causes a disease that is seasonal (spring & summer), with clinical signs of febrile disease, dyspnea, jaundice, and lab diagnostics showing pancytopenia, hyperbilirubinemia and schizont-laden macrophages on blood smear? A. -

Molecular Characterization of the North American Lung Fluke Paragonimus Kellicotti in Missouri and Its Development in Mongolian Gerbils Peter U

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2011 Molecular characterization of the North American lung fluke Paragonimus kellicotti in Missouri and its development in Mongolian gerbils Peter U. Fischer Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Kurt C. Curtis Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Luis A. Marcos Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Gary J. Weil Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Recommended Citation Fischer, Peter U.; Curtis, Kurt C.; Marcos, Luis A.; and Weil, Gary J., ,"Molecular characterization of the North American lung fluke Paragonimus kellicotti in Missouri and its development in Mongolian gerbils." American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.84,6. 1005-1011. (2011). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/1772 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 84(6), 2011, pp. 1005–1011 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0027 Copyright © 2011 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Molecular Characterization of the North American Lung Fluke Paragonimus kellicotti in Missouri and its Development in Mongolian Gerbils Peter U. Fischer ,* Kurt C. Curtis , Luis A. Marcos , and Gary J. Weil Infectious Diseases Division, Department of Internal Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri Abstract. Human paragonimiasis is an emerging disease in Missouri. -

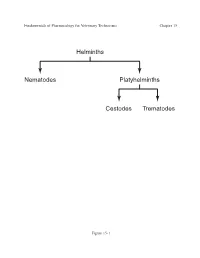

Helminths Nematodes Platyhelminths Cestodes Trematodes

Fundamentals of Pharmacology for Veterinary Technicians Chapter 15 Helminths Nematodes Platyhelminths Cestodes Trematodes Figure 15-1 Fundamentals of Pharmacology for Veterinary Technicians Chapter 15 TABLE 15-1 Helminths Encountered in Veterinary Medicine Scientific and Main Category Location of Parasite Commo Names Nematodes Abomasal worms in ruminants or stomach • Barberpole worm Haemonchus worms in monogastric animals contortus, H. placei (R) • Brown stomach worm Ostertagia ostertagi (R) • Small stomach worm or hairworm Trichostrongylus axei (R, H) • Hyostrongylus rubidus (Sw) • Large-mouth stomach worm Habronema muscae (H) Intestinal worms • Small intestinal worms Cooperia punctata, C. oncophora, C. mcmasteri (R) • Hookworms Bunostomum phlebotomum (R), Ancylostoma sp (D, F) • Nodular worms Oesophagostomum spp. (R, Sw) • Thread-necked intestinal worm Nematodirus helvetianus (R) • Bankrupt worm Trichostrongylus colubriformis (R) • Large strongyles Strongylus vulgaris, S. edentatus, S. equinus, Triodon- tophorus spp. (R, E) • Small strongyles Cyathostomum spp., Cylicocyclus spp., Cylicostephanus spp., Cylicodontophorus spp. (R) • Whipworms Trichuris suis (Sw), Trichuris vulpis (D) • Threadworms Strongyloides ransomi (Sw), Strongyloides westeri (E), Table 15-1 Fundamentals of Pharmacology for Veterinary Technicians Chapter 15 Strongyloides stercoralis (D) • Ascarids Parascaris equorum (H), Toxocara canis (D), Toxocara cati (F), Toxascaris leonina (D, F) • Pinworms Oxyuris equi (E) Circulatory systems worms • Heartworms Dirofilaria immitis