Your Lourdes Easter Week Special

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hearing Parables in the Patch by Joel Snider

80 Copyright © 2006 Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University Hearing Parables in the Patch BY JOEL SNIDER Clarence Jordan was an unusually able interpreter of Jesus’ parables. Not only his academic study, but also his small-town background and experiences in establish- ing the interracial Koinonia Farm in the 1940s shaped his ability to hear the parables in “the Cotton Patch.” ven a casual reading of the New Testament reveals that Jesus, though a carpenter by trade, used a large number of farming images in his Eteaching. Rural scenes and small-town settings provide the back- ground for much of his message. He talked about the difficulty of plowing in a straight line as an illustration of discipleship (Luke 9:62), described evangelists as harvest workers (Matthew 9:37), and interpreted his rejection at Nazareth in terms of small-town dynamics (Mark 6:4). Consequently, some of the cultural keys to understanding Jesus’ message lie in the rural and small-village life of ancient Palestine. This fact is particularly true when examining his parables. Like much of his other teachings, the stories of Jesus often reflect rural scenes and small- town dynamics. He spoke about a tenant farmer’s good luck as an analogy for discovering the gospel (Matthew 13:44) and described different types of soil as means of understanding various ways people receive the gospel (Mark 4:1-9; Matthew 13:1-9; Luke 8:4-8). Noxious weeds highlighted more than one of his stories (Matthew 13:24-30 and 13:31-32). You can easily think of other examples. -

Easter Resources (Selected Titles – More Will Be Added) Available To

Easter Resources (selected titles – more will be added) available to borrow from the United Media Resource Center http://www.igrc.org/umrc Contact Jill Stone at 217-529-2744 or by e-mail at [email protected] or search for and request items using the online catalog Key to age categories: P = preschool e = lower elementary (K-Grade 3) E = upper elementary (Grade 4-6) M = middle school/ junior high H = high school Y = young adult A = adult (age 30-55) S = adult (age 55+) DVDs: 24 HOURS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD (120032) Author: Hamilton, Adam. This seven-session DVD study will help you better understand the events that occurred during the last 24 hours of Jesus' life; to see more clearly the theological significance of Christ's suffering and death; and to reflect upon the meaning of these events for your life. DVD segments: Introduction (1 min.); 1) The Last Supper (11 min.); 2) The Garden of Gethsemane (7 min.); 3) Condemned by the Righteous (9 min.); 4) Jesus, Barabbas, and Pilate (9 min.); 5) The Torture and Humiliation of the King (9 min.); 6) The Crucifixion (13 min.); 7) Christ the Victor (11 min.); Bonus: What If Judas Had Lived? (5 min.); Promotional segment (1 min.). Includes leader's guide and hardback book. Age: YA. 77 Minutes. Related book: 24 HOURS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD: 40 DAYS OF REFLECTION (811018) Author: Hamilton, Adam. In this companion volume that can also function on its own, Adam Hamilton offers 40 days of reflection and meditation enabling us to pause, dig deeper, and emerge changed forever. -

Lent & Easter Resources

LENT & EASTER RESOURCES from the Resource Center January 2019 The SC Conference Resource Center is your connection to VHS tapes, DVD's and seasonal musicals. We are here to serve your church family. To reserve resources, call 1-803-786-9486. CHILDREN – DVD/VIDEO continues with the drama of Christ's betrayal, arrest and crucifixion—and his triumphant resurrection and ascent into Heaven. Age: PeE CHERUB WINGS: AND IT WAS SO (DVD176EC) 25 min./ 2000. In this Easter episode, a rousing space-chase in cherub JEREMY’S EGG (DVD1568EC) 95 min./1999. Twelve-year- chariots topples Cherub and Chubby into an awesome awareness old Jeremy is terminally ill and the only special-needs child in of God’s mighty power. Children will see the ultimate act of second grade. His teacher gives her students plastic eggs with the forgiveness in the crucifixion and the power of God in the instructions to fill them with something that symbolizes Easter Resurrection. This program shows how we can benefit from and new life. Jeremy's response to the assignment astonishes her, God’s daily presence in our lives. Ages 3-7. Age: PeE. his classmates, and the Navy pilot who is his friend. Based on a true story. Age: eEMHYAS. CHILDREN'S HEROES OF THE BIBLE: #2 NEW TESTAMENT (DVD1276C) 7 stories, 23 min. each. Animated READ AND SHARE BIBLE: EASTER (DVD1292EC) 30 Bible stories designed with a child's viewing habits in mind, and min./ 2010. Animated straight from the pages of the popular Read based squarely on Biblical accounts and interpreted at a child's and Share® Bible, this story of Easter is an uninterrupted half- level. -

Tom Chapin's Biography

Tom Chapin's Biography Born March 13, 1945, in New York, NY; father was a jazz drummer; married wife Bonnie, 1976; children: Abigail, Lily. Education: State University College at Plattsburgh, B.A. in history, 1969. Addresses: Record company-- Sundance Music, P.O. Box 1663, New York, NY 10011. Tom Chapin's early career may have been overshadowed by that of his more famous brother, singer-songwriter Harry Chapin of "Cat's in the Cradle" and "Taxi" fame, but Tom has made quite a name for himself as an eclectic songwriter and singer nonetheless. By the early 1990s, in fact, his music written especially for children, with its toe-tapping tunes and rich guitar accompaniments, had pleased parents so well that they generally think of his later body of work as "family" music rather than "kids" music. Considering his upbringing, Chapin was destined for a life in the arts. He grew up in New York City's Greenwich Village and Brooklyn Heights in a family that encouraged all the children to develop their creative talents. The senior Chapin, Jim, was a jazz drummer who performed with renowned bandleaders Tommy Dorsey and Woody Herman. One of Tom's grandfathers was a painter, and the other was a philosopher. When he was 12, Tom and his two brothers, Steve and Harry, fell under the influence of the seminal folk group the Weavers. The Chapin kids formed their own folk trio, calling themselves the Chapins. They played nightclub gigs in New York for a number of years and recorded their first album, Chapin Music!, in 1966. -

An Open Letter on Tama With

AN OPEN LETTER ON 2483 Easter Eve '91 TAMA WITH GOD ELLICaTTHINKSHEETS 309 L.Eliz.Dr., Craigville, MA 02636 Dear Phone 508.775.8008 Noncommercial reproduction permitted Here's what you asked me for, some notes toward a feature article on prayer in a secular magazine. Not long ago, most folks would think you were joking if you put "prayer" & "a secular magazine" in the same sentence. The fact that fewer now would laugh suggests why a secular magazine would be wise to have an article on prayer: the old secular securities & confidences are less satisfying now, providing an aperatura on the sacred, a window of opportunity for "spirituality" (the biggest word-bag for the fons et origo & raison d'etre of religion) . And of course you'd like to know where, right now, "prayer" is "newsworthy." Again, that's sounding less like an oxymoron than it would have a few years ago. My notes are helter-skelter, put down as they come to mind, in hope you may find something useful at least as stimulus. I've been pumping it all up into the tank & now am about to pull the chain. (You don't catch my reference? l cs. ago in Denmark, to take a shower you had first to pump the water up into the tank, then pull the chain. SK 11(ierkegaardl once pulled the chain & said to himself, "This isn't just the way I shower: it's also the way I write.") 1 I changed your "Talking TO God" to "Talking WITH God." Though the latter, being two-way, is truer to prayer, the former may make a better title for your article because (1) it's the more common phrase, because (2) it's what most people who pray think is going on when they pray (talking prayer being easier than talking-&-listening prayer). -

Lent & Easter Resources

LENT & EASTER RESOURCES from the Resource Center January 2020 The SC Conference Resource Center is your connection to DVD's and seasonal musicals. We are here to serve your church family. To reserve resources, call 1-803-786-9486. CHILDREN eternal life. Happy Easter? It doesn’t seem so. Nanny’s elderly friend Miss Peach dies. Isaiah doesn’t get a part in the school play, and their mother catches a “wicked” cold. But they discover A JELLY BEAN EASTER AND TWO the “little Easters” in life. Knowing God’s love turns Nanny and OTHER DRAMAS FOR CHILDREN: EASY Isaiah’s “downs” into “ups” sorrows into joy. Age: eE. DRAMAS, SPEECHES, AND RECITATIONS FOR (B1013DS) Author: FRIENDS AND HEROES (DVD2380C) 4 stories, 25 min Ingram, Shirley. 1.) A Jellybean Easter is an Easter story that each/access to supplemental materials/2017. Friends and Heroes helps children understand the significance of Easter by making uses creative storytelling and high-quality animation to teach, them aware of Jesus' sacrifice. It also celebrates the new life of entertain, and inspire children through exciting adventures and Christ and the new life of spring, which surrounds them. Ten life-changing Bible stories. Kindergarten - 6th grades. Friends speaking parts. The play lasts twenty-five minutes. 2.) The Easter and Heroes DVD 6: 10. Horseplay - Joseph and His Brothers Story tells the story of Easter from the triumphant entrance of (Genesis 37:1-4 & 18-36; Philip and Simon the Sorcerer (Acts Jesus into Jerusalem to the women's discovery of the empty tomb. 8:4-23); 11. -

The Echo: November 21, 1986

The Student ECHO of Taylor Taylor University, Upland, Indiana November 21,1986 "Ye Shall Know The Truth" issue ten Family, friends, feasting Thanksgiving thoughts by Karen Muselman giving to others! feature editor Angie Gollmer: Department stores and Traveling home, eating turkey, visiting communities are already celebrating Christmas. I Grandma, and relaxing with family and friends wish Thanksgiving and the meaning of Thanks commonly characterizes one's Thanksgiving giving had more of an emphasis in society. vacation. Marcia Benjamin: Being together with my With only five days left until the official holiday, family. Taylor University administration, faculty, staff and Russ Edwards: Reminds you that you have students are turning their thought toward the holiday friends because you eat turkey. with great anticipation. Shelly Glashagel: A time that I can be with In an opinion poll, the following individuals my family and Christian friends to thank God for answered the questions, "What is special to you what He has done in the last year. about Thanksgiving?" Rob Muthiah: Spending time with family Megan Rarick: Get away from worries, be and friends and a chance to recuperate from the with friends, and give thanks for what we have. turmoils of university life. Time to reflect on many Sarah Home: Simply being with my family blessings. and giving thanks. Crystal Handy: Being able to spend time Kent Nelson: A time when we re-emphasize with my family- Reunions! how thankful we are to live in this country, attend Andrew Lee: Vacations, family, turkeys, this college, and have wonderful parents. Tammy Rinard [In that order?-editor], and friends! Steve Huprich: Sharing together as a family. -

Special History Study, Jimmy Carter National Historic Site and Preservation District, 29

special history study november 1991 by William Patrick O'Brien JIMMY CARTER NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE AND PRESERVATION DISTRICT • GEORGIA UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR / NATIONAL PARK SERVICE TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v PREFACE vii INTRODUCTION 1 VISION STATEMENT 2 MAP - PLAINS AND VICINITY 3 PART ONE: BACKGROUND AND HISTORY BACKGROUND AND HISTORY 7 SOUTHWEST GEORGIA - REGION AND PLACE 9 SOUTHWEST GEORGIA - PEOPLE (PRE-HISTORY TO 1827) 11 SOUTHWEST GEORGIA, SUMTER COUNTY AND THE PLAINS OF DURA (1827-1865) 14 FROM THE PLAINS OF DURA TO JUST PLAIN "PLAINS" (1865-1900) 21 THE ARRIVAL AND PROGRESS OF THE CARTERS (1900-1920) 25 THE WORLD OF THE CARTERS AND JIMMY'S CHILDHOOD (1920-1941) 27 THE WORLD OUTSIDE OF PLAINS (1941-1953) 44 THE END OF THE OLD ORDER AND THE BEGINNING OF THE NEW: RETURN TO PLAINS (1953-1962) 46 ENTRY INTO POLITICS (1962-1966) 50 CARTER, PLAINS AND GEORGIA: YEARS OF CHANGE AND GROWTH - THE RISE OF THE NEW SOUTH (1966-1974) 51 PRESIDENTIAL VICTORY, PRESIDENTIAL DEFEAT (1974-1980) 55 THE CHRISTIAN PHOENIX AND THE "GLOBAL VILLAGE" - CARTER AND PLAINS (1980-1990) 58 CONCLUSION 63 PART TWO: INVENTORY AND. ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL RESOURCES - JIMMY CARTER NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE AND PRESERVATION DISTRICT INTRODUCTION 69 EXTANT SURVEY ELEMENTS - JIMMY CARTER NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE AND PRESERVATION DISTRICT 71 I. Prehistory to 1827 71 II. 1827-1865 72 III. 1865-1900 74 IV. 1900-1920 78 V. 1920-1941 94 VI. 1941-1953 100 iii VII. 1953-1962 102 VIII. 1962-1966 106 IX. 1966-1974 106 X. 1974-1980 108 XI. 1980-1990 109 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ADDITIONAL SURVEY ELEMENTS PLAINS, GEORGIA . -

The Peformative Grotesquerie of the Crucifixion of Jesus

THE GROTESQUE CROSS: THE PERFORMATIVE GROTESQUERIE OF THE CRUCIFIXION OF JESUS Hephzibah Darshni Dutt A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2015 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Charles Kanwischer Graduate Faculty Representative Eileen Cherry Chandler Marcus Sherrell © 2015 Hephzibah Dutt All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor In this study I argue that the crucifixion of Jesus is a performative event and this event is an exemplar of the Grotesque. To this end, I first conduct a dramatistic analysis of the crucifixion of Jesus, working to explicate its performativity. Viewing this performative event through the lens of the Grotesque, I then discuss its various grotesqueries, to propose the concept of the Grotesque Cross. As such, the term “Grotesque Cross” functions as shorthand for the performative event of the crucifixion of Jesus, as it is characterized by various aspects of the Grotesque. I develop the concept of the Grotesque Cross thematically through focused studies of representations of the crucifixion: the film, Jesus of Montreal (Arcand, 1989), Philip Turner’s play, Christ in the Concrete City, and an autoethnographic examination of Cross-wearing as performance. I examine each representation through the lens of the Grotesque to define various facets of the Grotesque Cross. iv For Drs. Chetty and Rukhsana Dutt, beloved holy monsters & Hannah, Abhishek, and Esther, my fellow aliens v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS St. Cyril of Jerusalem, in instructing catechumens, wrote, “The dragon sits by the side of the road, watching those who pass. -

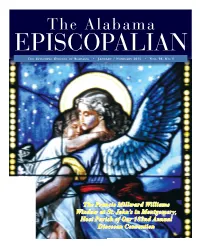

The Alabama Episcopalian T H E Ep I S C O P a L Di O C E S E O F Al a B a M a • Ja N U a Ry / Fe B R U a R Y 2013 • Vo L

The Alabama EPISCOPALIAN T h e ep i s c o p a l Di o c e s e o f al a b a m a • Ja n u a ry / fe b r u a r y 2013 • Vo l . 98, no. 1 The Francis Millward Williams Window at St. John’s in Montgomery, Host Parish of Our 182nd Annual Diocesan Convention 2 • The Alabama Episcopalian Around Our Diocese The Alabama Episcopalian January/February 2013 Continuing To Help Victims On the Cover Recover from Hurricane/ Superstorm Sandy By Diocesan Staff and Christine Turner, a Member of Trinity in Wetumpka Staten Island on Sunday and went directly to the Staten Island VFW, where we off-loaded the cleaning supplies The Francis Millward Williams Window at St. John’s in and some blankets. This area was very close to the shore Montgomery was given in memory of a child who died and served as a relief center for locals to get needed at a very young age; photo by Andrew Garner supplies and hot food. “We also took some blankets and jackets into the city in T h i s is s u e to Coney Island to a shelter that still did not have power. St. John’s in Montgomery is hosting our 182nd After we unloaded the supplies, we used our rental van Annual Diocesan Convention on February 22 and to help those at the relief center who were having a hard 23. The theme for this year and the next two annual time taking their supplies back to their temporary or conventions is “Invite, Inspire, Transform,” taken from permanent homes. -

Fourth Sunday of Epiphany February 3, 2019 Dr. Susan F. Dewyngaert

Fourth Sunday of Epiphany February 3, 2019 Dr. Susan F. DeWyngaert Love Actually Is All Around Jeremiah 1:4-10 1 Corinthians 12:31-13:13 The second reading today is among the most beautiful and best remembered chapters in the scriptures. Many people say 1 Corinthians 13 is their favorite chapter in the New Testament. It follows Paul’s discussion of spiritual gifts in chapter 12. The Apostle leaves absolutely no doubt which spiritual gift he thinks is the most important. It’s love. “Love, love, love…[singing] All you need is love.” Apologies to Lennon and McCartney! This is not a sugar-coated, Valentine’s Day love. This love is durable, resilient and resolute. This is love that endures. Hear again from Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians. But strive for the greater gifts. And I will show you a more excellent way. If I speak in the tongues of mortals and of angels, but do not have love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. And if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give away all my possessions, and if I hand over my body so that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing. Love is patient; love is kind; love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice in wrongdoing, but rejoices in the truth. -

Confessions of a Hoosier Christian Part II the Georgia Years

Confessions of a Hoosier Christian Part II The Georgia Years William W. Rogers Hanover, Indiana 1954 The Supreme Court's Decision to End Racial Segregation in the Public Schools and Ours to Accept an Invitation to Move South "When you feel the pain you know that you're alive." Big Daddy to his son, Brick, in Tennessee Williams', Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ii Part II Table of Contents Chapter 1: From Kalamazoo to Athens, Georgia A. Malcolm McIver's Visit Page 1 B. Meeting the Joint Committee 2 C. A Restatement of Purpose D. The Pattern of Ministry 3 E. Learning the Folkways and Mores of the Deep South 4 1. Andy McCullough Comes to Visit 2. Lillian Smith Speaks to the Westminster Fellowship 5 The Importance of a Book The Unfolding of a Play 6 3. Mr. Marable 8 F. Navigating the Waters of Change 9 1 A Study of Biblical Theology 2. The Growing Importance of Bonhoeffer, Tillich and Niebuhr 10 G. Three More Teachers 4. Hattie Jennings Visiting Hattie's Church 11 Taking Hattie to See the New Presbyterian Student Center 12 5. Eleanor Jordan 6. Betty Ann Conger 13 H. Reflections on the Georgia Reality iii Chapter 2: What Did We Learn and What Did We Do About It? A. Translating Evangelical Concepts into "Engaged Christianity" Page 14 1. Ye Must Be Born Again 2, The Decision for Christ 3. The Way of the Cross 15 4. The Sacrament of the Lord's Supper B. Putting Faith into Action 17 1. Taking a Stand for Desegregation 2.