Timing and Imaging Evidence in Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maze Storms to Giant Slalom Win

Warner puts Aussies on top as Test turns feisty 43 SATURDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2014 SATURDAY, SportsSports ARE: Tina Maze of Slovenia competes on her way to win an alpine ski, womenís World Cup giant slalom. —AP Maze storms to giant slalom win SWEDEN: Olympic champion Tina Maze consoli- tal globe last season, has 303. same venue and a women’s competition in on the Olympia course. Dopfer was .57 seconds dated her overall World Cup lead on Friday American superstar Lindsey Vonn sits sixth Courcheval, both slated for this weekend, had behind and American skier Ted Ligety trailed by when she produced a stunning second giant overall on 212pts thanks to her stunning Lake already been called off due to mild tempera- .81. Hirscher, who won the season-opening slalom run to clinch an impressive victory. Louise win last weekend. Maze, who was the tures and a lack of snow. giant slalom in Soelden, Austria, was looking to The Slovenian had trailed in seventh from Alpine skiing star at the Sochi Games after win- But the FIS said the women’s disciplines become the fifth Austrian to reach 25 World Cup the first leg earlier in the day in Are, but finished ning both the giant slalom and the downhill, would go ahead at Val d’Isere while a decision is wins. The race was moved from Val d’Isere to with a combined time of 2 minutes 23.84 sec- claimed she had been tired on the early run, but yet to be made on the men’s super-G and down- northern Sweden because of a lack of snow in onds, 0.2sec ahead of Sweden’s Sarah Hector woke up in time to save the day. -

MEN 100 METERS Jeffery Demps 90 Florida HS 10.01 16 2Q1 OT

MEN 100 METERS Jeffery Demps 90 Florida HS 10.01 16 2Q1 OT Eugene 28 Jun 08 Marcus Rowland 90 Auburn 10.03 7 1 PAG Jr Port-of-Spain 31 Jul 09 D’Angelo Cherry 90 Mississippi St 10.04 17 1H4 NCAA Fayetteville 10 Jun 09 Walter Dix 86 Florida St 10.06 15 1H1 NCAA East New York 27 May 05 Stanley Floyd 61 Auburn 10.07 20 1 Quad Cf Austin 24 May 80 DaBryan Blanton 84 Oklahoma 10.07 11 1H2 NCAA MW Lincoln 30 May 03 Andre Cason 69 Texas A&M 10.08 0 1 TAC Jr Tallahassee 24 Jun 88 Justin Gatlin 82 Tennessee 10.08 0 1 NCAA Eugene 2 Jun 01 J-Mee Samuels 87 North Carolina HS 10.08 7 1 Blunt Greensboro 24 Jul 05 Mel Lattany 59 Georgia 10.09A 18 2R2 USOF Colorado Springs 30 Jul 78 Stanley Kerr 67 Texas A&M 10.10 19 1 TAC Jr Towson 28 Jun 86 Harvey Glance 57 Auburn 10.11 19 1 OT Eugene 20 Jun 76 Tim Montgomery 75 Blinn CC 10.11 20 3H3 USATF Knoxville 15 Jun 94 Marks Made With Assisting Wind Leonard Scott 80 Tennessee 9.83 71 1 Sea Ray Knoxville 9 Apr 99 Walter Dix 86 Florida St 9.96 45 1R2 Tex R Austin 9 Apr 05 D’Angelo Cherry 90 Mississippi St 10.02 28 1H2 USATF Jr Eugene 26 Jun 09 Marcus Rowland 90 Auburn 10.02 24 1 USATF Jr Eugene 26 Jun 09 J-Mee Samuels 87 North Carolina HS 10.05 21 1S2 Blunt Greensboro 24 Jul 05 Marvin Bracy 93 Florida HS 10.05 22 1 USATF Jr Eugene 24 Jun 11 Lee McRae 66 Pittsburgh 10.07 29 2H5 NCAA Austin 30 May 85 Johnny Jones 58 Texas 10.08 41 1 Austin 20 May 77 Billy Fobbs 76 Texas A&M 10.08 22 1H3 Hous Inv Houston 19 May 95 Prezel Hardy 92 Texas HS 10.08 22 1 State 5A Austin 6 Jun 09 Stanley Blalock 64 Georgia 10.09 41 1 Ga Rel Athens, Ga 19 Mar 83 Rodney Bridges 71 Cen Ariz CC 10.10 1S1 JUCO Odessa 18 May 90 Rod Richardson 62 Texas A&M 10.11 40 1 Tex Inv Austin 22 May 81 Illegal Wind Gauge (Course 4 Cm. -

— NCAA Women: A&M Defends Here Too —

Volume 9, No. 37 June 15, 2010 version iii — NCAA Women: A&M Defends Here Too — by Jon Hendershott to the meet, Oregon and A&M battled down gave the Aggies a second consecutive sweep Eugene, Oregon, June 9–12—After the to literally the final stride of the 4x4 before of both the men’s and women’s titles. third day of the 29th edition of the NCAA UO’s Keisha Baker just prevailed ahead of “Everybody knew it was about the team,” Women’s Championships, host Oregon led A&M’s Jessica Beard by 0.03 in 3:28.54. said Henry afterward, clutching individual the team scoring with 30 points. But A&M’s final total of 72 kept the plaques for both wins. “That’s what we talked Tied for 3rd at 26, defender Texas A&M champion’s trophy in College Station and about all year long, so this wasn’t an excep- figured to pull in final- tion. It’s about responding to day points in the speed ups and downs.” events. Lucas came up And A&M came to Eugene And so the Aggies huge for the after two major downs: inju- did. After retaining their ries to hurdlers Gabby Mayo 4 x 100 title by nearly a Aggies, picking up (also a key leg on the 4x1) and second with a 42.82 ef- Natasha Ruddock. Both were fort (with a patchwork a pair of wins (200, injured at Regionals, Mayo lineup), suddenly the 4x1) and a 2nd (100) with a strained left quad and two powerhouses were Ruddock with a torn ACL. -

The Race of Future Champions U8

26–28/1/2018 THE RACE OF FUTURE CHAMPIONS U8 | U10 | U12 | U14 | U16 HIGHLIGHTS Little Fox race on the World Cup Golden Fox slope Saturday: Giant slalom U8 - U16 Sunday: Clubs go head-to-head in giant slalom relay The race of future champions Main prize: 5-day cruise on the Adriatic sea PROGRAMME FRIDAY, 26 JANUARY 2018 9:00–16:00 / Snow Stadium, Pohorje · Lifts open · Free skiing 9:00–21:00 / Finish Area, Accreditation Centre · Check-in, distribution of race bibs and goody bags (for first 500 applicants) + official photo shoot for personal videos 17:30 / Finish Area & Snow Stadium, Pohorje · The official Opening Ceremony GOODY BAG *for first 500 applicants ORGANISER ENTRY FEE Saturday, GS race = € 25 The entry fee includes the GS race, A a goody bag (a race bib, a hoody…), a medal, M Alpski smučarski klub Branik Maribor a personal video and a free pasta party E D Mladinska ulica 29, 2000 Maribor / Slovenia A L Information: Sunday, Team event = €40 F O Manca Kravina (for the rest of the teams from the same club R E R [email protected] the entry fee is €20) AC ITO H ET +386 41 678 315 COMP SATURDAY, 27 JANUARY 2018 SUNDAY, 28 JANUARY 2018 7:30 / Snow Stadium, Pohorje 7:30 / Snow Stadium, Pohorje · Lifts open · Lifts open · Free skiing 8:00–8:30 / Snow Stadium, Pohorje · Course inspection for U8, U10 and U12 8:00–15:00/ Finish Area, Teams Hospitality Area · Games and fun for kids 9:00 / Snow Stadium, Pohorje · After 12 pm: Pasta Party · Start of the race for U8, U10 and U12 8:15–8:30 / Snow Stadium, Pohorje 7:00–17:00 / Finish -

Doma V Mariboru

Zlata lisica. Doma v Mariboru. 56 nepozabnih lisičjih zgodb Naslovka.indd 2 29/01/2020 13:38 02 56. ZGODBO ZLATE LISICE PIŠEMO SKUPAJ Za nas Štajerce, ki smo Pohorje vedno imeli pred očmi, je Zlata lisica zmeraj pomenila najpomembnejšo športno prireditev v vsakem letu in za naše športne junakinje smo vedno srčno in glasno navijali. Na Pohorje sem se sicer vselej z največjim veseljem vračal, pa če je šlo za dnevno smučarijo, poletne priprave namiznoteniškega kluba ali pa le ob pogledu iz družinskega vinograda, ko se pred očmi za Ptujskim in Dravskim poljem razgrne v vsej mogočnosti. Čeravno sem sam zgolj rekreativni smučar in sem bil tekmovalno zapisan namiznemu tenisu, občudujem vse slovenske športnice in športnike, ki s trdim delom predano sledijo postavljenim ciljem, imajo najvišje ambicije in dosegajo izjemne rezultate v svetovnem merilu. V športu je vse jasno in običajno ni prostora za iskanje izgovorov. Podobno filozofijo gojijo tudi slovenske podjetnice in podjetniki, ki dosegajo vse boljše rezultate v globalni konkurenci. Vnaprej se veselim časa, ko si bomo tudi v oblastnih strukturah in Za to skrbimo na več načinov. Najprej s resnično neugodnih razmerah pokazati sistemskih institucijah postavili enake cilje. svojim znanjem in storitvami, usmerjenimi še posebno veliko požrtvovalnosti in Da bomo kot družba med najboljšimi na k strankam, s prepoznavanjem priložnosti predanosti, za kar se ji v NLB zahvaljujemo svetu in bomo za to trdo in predano delali, in potreb lokalnega okolja, z uspešnim in ji čestitamo. Prepričani smo, da bodo vse ne pa kot v zadnjem desetletju v glavnem poslovanjem ter s promocijo slovenskega od sebe dali tudi v njenem drugem domu, iskali bližnjice in izgovore, zakaj nam ne gospodarstva. -

Girls 100 Meters Performance State Year Time 1 Candace Hill GA 2015 10.98 2 Kaylin Whitney FL 2014 11.10 3 Angela Williams CA 19

Girls 100 Meters Performance State Year Time 1 Candace Hill GA 2015 10.98 2 Kaylin Whitney FL 2014 11.10 3 Angela Williams CA 1998 11.11 4 Chandra Cheeseborough FL 1976 11.13 Ashley Owens CO 2004 6 Marion Jones CA 1992 11.14 7 Gabby Mayo NC 2006 11.16 Victoria Jordan TX 2008 Octavious Freeman FL 2010 10 Wendy Vereen NJ 1983 11.17 Ashton Purvis CA 2010 12 Aleisha Latimer CO 1997 11.19 Khalifa St. Font FL 2015 14 Tiffany Townsend TX 2007 11.21 15 Chalonda Goodman GA 2009 11.22 Ariana Washington CA 2014 17 Jeneba Tarmoh CA 2006 11.24 MaryBeth Sant CO 2013 Teahna Daniels FL 2015 Symone Mason FL 2017 20 Bianca Knight MS 2006 11.26 Zaria Francis CA 2015 Katia Seymour FL 2016 23 Angela Burnham CA 1988 11.28 Sha'carri Richardson TX 2017 24 Allyson Felix CA 2003 11.29 25 Margaret Bailes OR 1968 11.30 26 Shataya Hendricks FL 2007 Briana Williams FL 2017 27 Jessica Onyepuunka AZ 2003 11.31 28 Erica Whipple FL 2000 11.32 29 Jasmine Baldwin CA 2004 11.33 Elizabeth Olear CA 2006 Shayla Sanders FL 2012 Ana Holland CO 2013 Ky Westbrook AZ 2013 Alfreda Steele FL 2015 35 Sharon Ware CA 1980 11.34 Jenna Prandini CA 2010 Krystal Sparling FL 2014 Kaylor Harris TX 2016 40 Caryl Smith CO 1987 11.35 Zundra Feagin FL 1990 Shalonda Solomon CA 2003 43 Danielle Marshall WA 1992 11.36 Aspen Burkett CO 1994 Muna Lee MO 2000 Kenyanna Wilson AZ 2006 47 Shayla Mahan MI 2007 11.37 Dominque Duncan TX 2008 Lauren Rain Williams CA 2015 Twanisha Terry FL 2017 50 Casey Custer TX 1992 11.38 Dezerea Bryant WA 2011 52 Khalilah Carpenter OH 2000 11.39 Sanya Richards FL 2002 Alexandria -

2014-15 BAYLOR CROSS COUNTRY/TRACK and FIELD MEDIA ALMANAC Sixth Edition, Baylor Athletic Communications

2014-15 BAYLOR CROSS COUNTRY/TRACK AND FIELD MEDIA ALMANAC Sixth Edition, Baylor Athletic Communications www.BaylorBears.com | www.Facebook.com/BaylorAthletics | www.Twitter.com/BaylorAthletics BAYLOR UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ATHLETICS 1500 South University Parks Drive Waco, TX 76706 254-710-1234 www.BaylorBears.com Facebook: BaylorAthletics Twitter: @BaylorAthletics CREDITS EDITORS Sean Doerre, Nick Joos, David Kaye COMPILATION Sean Doerre PHOTOGRAPHY Robbie Rogers, Matthew Minard Baylor Photography Marketing & Communications © 2015, Baylor University Department of Athletics BAYLOR UNIVERSITY MISSION STATEMENT The mission of Baylor University is to educate men and women for worldwide leadership and service by integrating academic excellence and Christian commitment within a caring community. BAYLOR ATHLETICS MISSION STATEMENT To support the overall mission of the University by providing a nationally competitive intercollegiate athletics program that attracts, nurtures and graduates student-athletes who, under the guidance of a high-quality staff, pursue excellence in their respective sports, while representing Baylor with character and integrity. Consistent with the Christian values of the University, the department will carry out this mission in a way that reflects fair and equitable opportunities for all student-athletes and staff. Baylor University is an equal opportunity institution whose programs, services, activities and operations are without discrimination as to sex, color, or national origin, and are not opposed to qualified handi capped persons. 2014-15 BAYLOR CROSS COUNTRY/TRACK AND FIELD MEDIA ALMANAC @BAYLORTRACK TABLE OF CONTENTS INFORMATION 1-5 MEDIA INFORMATION INFORMATION Table of Contents . .1 GENERAL INFORMATION Athletic Communications Staff . .2 Location Waco, Texas University Administration . .3 Chartered 1845 by the Republic of Texas Director of Athletics . -

IAAF WORLD RECORDS - MEN As at 1 January 2018 EVENT PERF

IAAF WORLD RECORDS - MEN as at 1 January 2018 EVENT PERF. WIND ATHLETE NAT PLACE DATE TRACK EVENTS 100m 9.58 0.9 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin, GER 16 Aug 09 200m 19.19 -0.3 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin, GER 20 Aug 09 400m 43.03 Wayde van NIEKERK RSA Rio de Janeiro, BRA 14 Aug 16 800m 1:40.91 David Lekuta RUDISHA KEN London, GBR 9 Aug 12 1000m 2:11.96 Noah NGENY KEN Rieti, ITA 5 Sep 99 1500m 3:26.00 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR Roma, ITA 14 Jul 98 1 Mile 3:43.13 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR Roma, ITA 7 Jul 99 2000m 4:44.79 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR Berlin, GER 7 Sep 99 3000m 7:20.67 Daniel KOMEN KEN Rieti, ITA 1 Sep 96 5000m 12:37.35 Kenenisa BEKELE ETH Hengelo, NED 31 May 04 10,000m 26:17.53 Kenenisa BEKELE ETH Bruxelles, BEL 26 Aug 05 20,000m 56:26.0 Haile GEBRSELASSIE ETH Ostrava, CZE 27 Jun 07 1 Hour 21,285 Haile GEBRSELASSIE ETH Ostrava, CZE 27 Jun 07 25,000m 1:12:25.4 Moses Cheruiyot MOSOP KEN Eugene, USA 3 Jun 11 30,000m 1:26:47.4 Moses Cheruiyot MOSOP KEN Eugene, USA 3 Jun 11 3000m Steeplechase 7:53.63 Saif Saaeed SHAHEEN QAT Bruxelles, BEL 3 Sep 04 110m Hurdles 12.80 0.3 Aries MERRITT USA Bruxelles, BEL 7 Sep 12 400m Hurdles 46.78 Kevin YOUNG USA Barcelona, ESP 6 Aug 92 FIELD EVENTS High Jump 2.45 Javier SOTOMAYOR CUB Salamanca, ESP 27 Jul 93 Pole Vault 6.16i Renaud LAVILLENIE FRA Donetsk, UKR 15 Feb 14 Long Jump 8.95 0.3 Mike POWELL USA Tokyo, JPN 30 Aug 91 Triple Jump 18.29 1.3 Jonathan EDWARDS GBR Göteborg, SWE 7 Aug 95 Shot Put 23.12 Randy BARNES USA Los Angeles, USA 20 May 90 Discus Throw 74.08 Jürgen SCHULT GDR Neubrandenburg, GDR 6 Jun 86 Hammer Throw -

Oly Roster CA-PA

2012 Team USA Olympic Roster (including Californians and Pacific Association/USATF athletes) (Compiled by Mark Winitz) Key Blue type indicates California residents, or athletes with strong California ties Green type indicates Californians who are Pacific Association/USATF members, or athletes with strong Pacific Association ties Bold type indicates past World Outdoor or Olympic individual medalist * Relay pools are composed of the 100m and 400m rosters, the athletes listed in each pool, plus any athlete already on the roster in any other event * All nominations are pending approval by the USOC board of directors. MEN 100m – Justin Gatlin (Orlando, Fla.), Tyson Gay (Clermont, Fla.), Ryan Bailey (Salem, Ore.) 200m – Wallace Spearmon (Dallas, Texas), Maurice Mitchell (Tallahassee, Fla.), Isiah Young (Lafayette, Miss.) 400m – LaShawn Merritt (Suffolk, Va.), Tony McQuay (Gainesville, Fla.), Bryshon Nellum (Los Angeles, Calif.) 800m – Nick Symmonds (Springfield, Ore.), Khadevis Robinson (Las Vegas, Nev.; former longtime Los Angeles-area resident), Duane Solomon (Los Angeles, Calif.) 1500 m– Leonel Manzano (Austin, Texas), Matthew Centrowitz (Eugene, Ore.), Andrew Whetting (Eugene, Ore.) 3000m Steeplechase – Evan Jager (Portland, Ore.), Donn Cabral (Conn.), Kyle Alcorn (Mesa, Ariz.; Buchanan H.S. /Clovis, Calif. '03) 5000m – Galen Rupp (Portland, Ore.), Bernard Lagat (Tucson, Ariz.), Lopez Lomong (Beaverton, Ore.) 10,000m – Galen Rupp (Portland, Ore.), Matt Tegenkamp (Portland, Ore.), Dathan Ritzenhein (Portland, Ore.) 20 km Race Walk – Trevor -

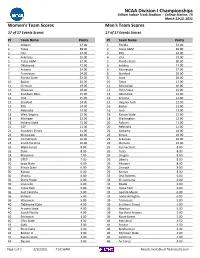

Crystal Reports

NCAA Division I Championships Gilliam Indoor Track Stadium ͲͲ College Station, TX March 11Ͳ12, 2011 Women's Team Scores Men's Team Scores 17 of 17 Events Scores 17 of 17 Events Scores Pl Team Name Points Pl Team Name Points 1Oregon 67.00 1FloriDa 52.00 2Texas 38.00 2Texas A&M 40.00 3LSU 37.00 3BYU 34.00 4Arkansas 35.00 4LSU 31.00 5Texas A&M 32.00 5FloriDa State 30.00 6Oklahoma 25.00 6InDiana 27.00 7Arizona 24.00 6Minnesota 27.00 7Tennessee 24.00 8StanforD 20.00 9FloriDa State 22.00 8IoWa 20.00 10 Baylor 20.00 10 Texas 17.00 11 Clemson 19.00 11 Mississippi16.00 12 Villanova 18.00 11 Penn State 16.00 13 Southern Miss. 15.00 13 Oklahoma 14.00 13 TCU 15.00 13 Arizona 14.00 15 Stanford 14.00 15 Virginia Tech 13.50 15 BYU 14.00 16 Baylor 13.00 17 Nebraska 13.00 16 Iona 13.00 18 West Virginia 12.00 18 Kansas State 12.00 18 Michigan 12.00 18 Washington 12.00 18 Indiana State 12.00 20 Auburn 11.00 21 UCF 11.00 20 Nebraska 11.00 21 Southern Illinois 11.00 22 Alabama 10.00 23 Mississippi10.0022 Illinois 10.00 23 Connecticut 10.00 22 Arkansas 10.00 23 South Carolina 10.00 22 Clemson 10.00 26 Wake Forest 8.00 26 Connecticut 8.00 26 Duke 8.00 26 Tulsa 8.00 28 Maryland 7.00 26 Oregon 8.00 28 UTEP 7.00 26 Liberty 8.00 30 Iowa State 6.00 26 Missouri 8.00 30 Illinois State 6.00 26 Georgia 8.00 30 Kansas 6.00 26 Kansas 8.00 30 Virginia 6.00 33 Oral Roberts 6.00 30 Stony Brook 6.00 33 SE Louisiana 6.00 30 Louisville 6.00 33 Miami 6.00 36 Texas Tech 5.00 33 Texas Tech 6.00 36 East Carolina 5.00 33 George Mason 6.00 36 Indiana 5.00 33 TexasͲArlington 6.00 36 Wisconsin 5.00 39 Tennessee 5.00 40 Oklahoma State 4.00 39 Southern Illinois 5.00 40 Arizona State 4.00 39 Houston 5.00 40 South Florida 4.00 39 Northern Arizona 5.00 40 Princeton 4.00 39 Notre Dame 5.00 40 Ohio State 4.00 44 Maryland 4.50 45 SMU 3.00 44 Purdue 4.50 45 Penn State 3.00 46 Binghamton 4.00 45 Boston U. -

RESULTS 100 Metres Women - Final

Moscow (RUS) World Championships 10-18 August 2013 RESULTS 100 Metres Women - Final RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE DATE VENUE World Record 10.49 Florence GRIFFITH-JOYNER USA 29 16 Jul 1988 Indianapolis, IN Championships Record 10.70 Marion JONES USA 24 22 Aug 1999 Sevilla World Leading 10.71 Shelly-Ann FRASER-PRYCE JAM 27 12 Aug 2013 Moscow TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY WIND START TIME 21:49 19° C 73 % -0.3 m/s Final 12 August 2013 PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 510 Shelly-Ann FRASER-PRYCE JAM 27 Dec 86 4 10.71 WL 0.174 Шелли -Энн Фрейзер -Прайс 27 дек . 86 2 254 Murielle AHOURE CIV 23 Aug 87 6 10.93 0.165 Мюриэлль Аур 23 авг . 87 3 921 Carmelita JETER USA 24 Nov 79 5 10.94 0.156 Кармелита Джетер 24 нояб . 79 4 908 English GARDNER USA 22 Apr 92 2 10.97 0.151 Инглиш Гарднер 22 апр . 92 5 519 Kerron STEWART JAM 16 Apr 84 8 10.97 0.229 Керрон Стюарт 16 апр . 84 6 635 Blessing OKAGBARE NGR 09 Oct 88 7 11.04 0.154 Блессинг Окагбаре 09 окт . 88 7 881 Alexandria ANDERSON USA 28 Jan 87 3 11.10 0.159 Александриа Андерсон 28 янв . 87 8 907 Octavious FREEMAN USA 20 Apr 92 9 11.16 0.179 Октавиус Фриман 20 апр . 92 ALL-TIME TOP LIST SEASON TOP LIST RESULT NAME Venue DATE RESULT NAME Venue DATE 10.49 Florence GRIFFITH-JOYNER (USA) Indianapolis, IN 16 Jul 88 10.71 Shelly-Ann FRASER-PRYCE (JAM) Moscow 12 Aug 13 10.64 Carmelita JETER (USA) Shanghai 20 Sep 09 10.79 Blessing OKAGBARE (NGR) London (OP) 27 Jul 13 10.65 Marion JONES (USA) Johannesburg 12 Sep 98 10.83 Kelly-Ann BAPTISTE (TRI) Port-of-Spain 22 Jun 13 10.70 Shelly-Ann FRASER-PRYCE -

Maria PH Och Anja Bland Topp 3?

2008-11-27 13:53 CET Maria PH och Anja bland topp 3? På lördag är det dags för damernas storslalom i Aspen.Som favoriter har vi Karin Zettel och Denise Karbon båda till odds 4,50. Hamnar Anja Pärsson eller Maria PH bland topp 3 i storslalom ger det 3,50 respektive 4,50 gånger pengarna. När det gäller slalom har Maria PH haft en bra start då hon kom tvåa i Levi och att hon lyckas med topp 3 igen ger 3,25 i odds. Det kommer att bli en jämn match mellan favoriterna Zettel och Karbon där båda ger 1,85 i odds. Mellan våra svenska damer, Anja Pärson och Maria PH ser även det ut som en jämn match men Pärson är knapp favorit till odds 1,75. Gör Maria PH ett bättre lopp ger det 2 gånger pengarna. Aktuella odds Alpint: Anja Pärson specialare: Anja Pärson slutar bland topp 3 i storslalom i Aspen 29/11/08 -3,50 Anja Pärson slutar bland topp 5 i storslalom i Aspen29/11/08 -2,00 Anja Pärson slutar bland topp 3 i Slalom i Aspen 30/11/08 -3,50 Anja Pärson slutar bland topp 5 i Slalom i Aspen 30/11/08 -2,00 Maria Pietilä-Holmner specialare: Maria PH slutar bland topp 3 i storslalom i Aspen 29/11/08 - 4,50 Maria PH slutar bland topp 5 i storslalom i Aspen 29/11/08 - 2,25 Maria PH slutar bland topp 3 i slalom i Aspen 30/11/08 - 3,25 Maria PH slutar bland topp 5 i slalom i Aspen 30/11/08 - 1,90 Head to head: Katrin Zettel 1,85 Denise Karbon 1,85 Anja Pärson 1,75 Maria Pietilä-Holmner 2,00 Vinnare storslalom 29 november: Katrin Zettel 4,50 Denise Karbon 4,50 Tanja Poutiainen 6,00 Elisabeth Goergl 10,00 Nicole Hosp 10,00 Manuela Moelgg 13,00 Julia Mancuso 13,00