Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kretan Cult and Customs, Especially in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods: a Religious, Social, and Political Study

i Kretan cult and customs, especially in the Classical and Hellenistic periods: a religious, social, and political study Thesis submitted for degree of MPhil Carolyn Schofield University College London ii Declaration I, Carolyn Schofield, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been acknowledged in the thesis. iii Abstract Ancient Krete perceived itself, and was perceived from outside, as rather different from the rest of Greece, particularly with respect to religion, social structure, and laws. The purpose of the thesis is to explore the bases for these perceptions and their accuracy. Krete’s self-perception is examined in the light of the account of Diodoros Siculus (Book 5, 64-80, allegedly based on Kretan sources), backed up by inscriptions and archaeology, while outside perceptions are derived mainly from other literary sources, including, inter alia, Homer, Strabo, Plato and Aristotle, Herodotos and Polybios; in both cases making reference also to the fragments and testimonia of ancient historians of Krete. While the main cult-epithets of Zeus on Krete – Diktaios, associated with pre-Greek inhabitants of eastern Krete, Idatas, associated with Dorian settlers, and Kretagenes, the symbol of the Hellenistic koinon - are almost unique to the island, those of Apollo are not, but there is good reason to believe that both Delphinios and Pythios originated on Krete, and evidence too that the Eleusinian Mysteries and Orphic and Dionysiac rites had much in common with early Kretan practice. The early institutionalization of pederasty, and the abduction of boys described by Ephoros, are unique to Krete, but the latter is distinct from rites of initiation to manhood, which continued later on Krete than elsewhere, and were associated with different gods. -

Bacchylides 17: Singing and Usurping the Paean Maria Pavlou

Bacchylides 17: Singing and Usurping the Paean Maria Pavlou ACCHYLIDES 17, a Cean commission performed on Delos, has been the subject of extensive study and is Bmuch admired for its narrative artistry, elegance, and excellence. The ode was classified as a dithyramb by the Alex- andrians, but the Du-Stil address to Apollo in the closing lines renders this classification problematic and has rather baffled scholars. The solution to the thorny issue of the ode’s generic taxonomy is not yet conclusive, and the dilemma paean/ dithyramb is still alive.1 In fact, scholars now are more inclined to place the poem somewhere in the middle, on the premise that in antiquity the boundaries between dithyramb and paean were not so clear-cut as we tend to believe.2 Even though I am 1 Paean: R. Merkelbach, “Der Theseus des Bakchylides,” ZPE 12 (1973) 56–62; L. Käppel, Paian: Studien zur Geschichte einer Gattung (Berlin 1992) 156– 158, 184–189; H. Maehler, Die Lieder des Bakchylides II (Leiden 1997) 167– 168, and Bacchylides. A Selection (Cambridge 2004) 172–173; I. Rutherford, Pindar’s Paeans (Oxford 2001) 35–36, 73. Dithyramb: D. Gerber, “The Gifts of Aphrodite (Bacchylides 17.10),” Phoenix 19 (1965) 212–213; G. Pieper, “The Conflict of Character in Bacchylides 17,” TAPA 103 (1972) 393–404. D. Schmidt, “Bacchylides 17: Paean or Dithyramb?” Hermes 118 (1990) 18– 31, at 28–29, proposes that Ode 17 was actually an hyporcheme. 2 B. Zimmermann, Dithyrambos: Geschichte einer Gattung (Hypomnemata 98 [1992]) 91–93, argues that Ode 17 was a dithyramb for Apollo; see also C. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 12 | 1999 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.724 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1999 Number of pages: 207-292 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 », Kernos [Online], 12 | 1999, Online since 13 April 2011, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 Kernos Kemos, 12 (1999), p. 207-292. Epigtoaphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 (EBGR 1996) The ninth issue of the BEGR contains only part of the epigraphie harvest of 1996; unforeseen circumstances have prevented me and my collaborators from covering all the publications of 1996, but we hope to close the gaps next year. We have also made several additions to previous issues. In the past years the BEGR had often summarized publications which were not primarily of epigraphie nature, thus tending to expand into an unavoidably incomplete bibliography of Greek religion. From this issue on we return to the original scope of this bulletin, whieh is to provide information on new epigraphie finds, new interpretations of inscriptions, epigraphieal corpora, and studies based p;imarily on the epigraphie material. Only if we focus on these types of books and articles, will we be able to present the newpublications without delays and, hopefully, without too many omissions. -

Local Information

7th Workshop on Dynamic Macroeconomics Mykonos, Greece, 1-3 October 2009 Local Information 1 Accommodation Accommodation has been reserved at the Rocabella Mykonos Hotel. Rocabella Art Hotel Mykonos Agios Stefanos, 84600, Mykonos, Cyclades Islands, Greece Tel:(+30) 22890 28930 Fax:(+30) 22890 79720 http://www.rocabella-hotel-mykonos.com/ The Rocabella art Hotel and Spa is situated near Agios Stefanos, a small town, offering a fully - serviced beach with crystal clear waters, restaurants, lifeguards, sun beds and umbrellas, located in the north The transfer to and from the airport/port as well as the transportation to the restaurants and the trips to the town will be done with the hotel shuttle buses (free of charge) The conference venue is the Rocabella Mykonos Hotel Conference Room. An overhead projector and laptop will be available. Meals Æ American Buffet breakfast will be served on Rocabella Hotel. Æ Light lunches will be offered during the workshop at the hotel. 2 Dinners Thursday 1 October 2009: Restaurant - Fish tavern, “Η Epistrophi”, St.Stefanos On the beautiful and graphic beach of St. Stefanou, with the fantastic view in the Chora of Mykonos and Delos. http://www.epistrofirestaurant.com/index_uk.html (5’ walking distance from Rocabella Hotel) Friday 2 October 2009: Greek Cuisine Restaurant, President’s Place, Ano Mera Inland, about 9 km from Mykonos town, stands Ano Mera, the most populated village (other than Mykonos town) on the island. http://www.steki-proedrou.com/english/index.php (15’ by mini bus from Rocabella Hotel) Saturday 3 October 2009: Azzurro Mediterranean cuisine: Blu Restaurant, Old Port Right next to Blue - Blue café, with VIP veranda as highlight (with view in the Chora of Mykonos, Delos and Old Port). -

Mecoptera: Meropeidae): Simply Dull Or Just Inscrutable?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 8-24-2007 Etymology of the earwigfly, Merope tuber Newman (Mecoptera: Meropeidae): Simply dull or just inscrutable? Louis A. Somma University of Florida, [email protected] James C. Dunford University of Florida, Gainesville, FL Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Entomology Commons Somma, Louis A. and Dunford, James C., "Etymology of the earwigfly, Merope tuber Newman (Mecoptera: Meropeidae): Simply dull or just inscrutable?" (2007). Insecta Mundi. 65. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0013 Etymology of the earwigfly, Merope tuber Newman (Mecoptera: Meropeidae): Simply dull or just inscrutable? Louis A. Somma Department of Zoology PO Box 118525 University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611-8525 [email protected] James C. Dunford Department of Entomology and Nematology PO Box 110620, IFAS University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611-0620 [email protected] Date of Issue: August 24, 2007 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL Louis A. Somma and James C. Dunford Etymology of the earwigfly, Merope tuber Newman (Mecoptera: Meropeidae): Simply dull or just inscrutable? Insecta Mundi 0013: 1-5 Published in 2007 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. P. O. Box 147100 Gainesville, FL 32604-7100 U. -

Preliminary Studies on the Scholia to Euripides

Preliminary Studies on the Scholia to Euripides CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES NUMBER 6 Editorial Board Chair: Donald Mastronarde Editorial Board: Alessandro Barchiesi, Todd Hickey, Emily Mackil, Richard Martin, Robert Morstein-Marx, J. Theodore Peña, Kim Shelton California Classical Studies publishes peer-reviewed long-form scholarship with online open access and print-on-demand availability. The primary aim of the series is to disseminate basic research (editing and analysis of primary materials both textual and physical), data-heavy re- search, and highly specialized research of the kind that is either hard to place with the leading publishers in Classics or extremely expensive for libraries and individuals when produced by a leading academic publisher. In addition to promoting archaeological publications, papyrologi- cal and epigraphic studies, technical textual studies, and the like, the series will also produce selected titles of a more general profile. The startup phase of this project (2013–2017) is supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Also in the series: Number 1: Leslie Kurke, The Traffic in Praise: Pindar and the Poetics of Social Economy, 2013 Number 2: Edward Courtney, A Commentary on the Satires of Juvenal, 2013 Number 3: Mark Griffith, Greek Satyr Play: Five Studies, 2015 Number 4: Mirjam Kotwick, Alexander of Aphrodisias and the Text of Aristotle’s Metaphys- ics, 2016 Number 5: Joey Williams, The Archaeology of Roman Surveillance in the Central Alentejo, Portugal, 2017 PRELIMINARY STUDIES ON THE SCHOLIA TO EURIPIDES Donald J. Mastronarde CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES Berkeley, California © 2017 by Donald J. Mastronarde. California Classical Studies c/o Department of Classics University of California Berkeley, California 94720–2520 USA http://calclassicalstudies.org email: [email protected] ISBN 9781939926104 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017916025 CONTENTS Preface vii Acknowledgments xi Abbreviations xiii Sigla for Manuscripts of Euripides xvii List of Plates xxix 1. -

Persephone: Symbol of Rebirth

SECTION II CHAPTER 7 PERSEPHONE: SYMBOL OF REBIRTH PAPER CONTENTS INTRODUCTION MYTHIC TALE: SYNOPSIS LORD HADES: ARCHETYPE OF THE DEATH FORCE DEMETER: ARCHETYPE OF THE LIFE FORCE THE UNDERWORLD: WORLD OF SHADOWS AND SOULS PERSEPHONE: THE WAY OF THE FEMININE Name and Origins Daughterhood Abduction and Marriage Pomegranate Judgment of Seasons Motherhood Queenhood Deep Feminine Caretaker of Souls RETURN AND REBIRTH FEMININE INDIVIDUATION CLOSING COMENTS 1 INTRODUCTION The mythic tale of Persephone’s abduction by Hades, the personification of the Death Force, and the unremitting search by her mother, Demeter, Goddess exemplar of the Life Force, relates a fascinating account of how Death and Life Forces interact with each other. In the tale, Persephone holds the tension between Life and Death Forces and in doing so produces a new alterative, Rebirth. As maiden she is ever ready to birth, to give Life. Although Persephone's name means 'Bringer of Destruction', as Queen of the Underworld she regenerates the Souls that come to her realm. The mythic tale suggests that the resolution of the tension between Life and Death leads to the transcendent third. The prior two chapters focus on transformation that is needed for the feminine to carry out the “return” from its suppressed state. The chapter on Pele and Hi’iaka brought attention to feminine transformation that occurred when relationship based on fertility gave way to relationship based on personal encounter. The chapter on The Goose Girl addresses the transformation that leads to feminine personhood when daughter separates from the mother. In this chapter attention is given to the transformation that rebirth brings about, namely, enabling and revitalizing the Individuation Process. -

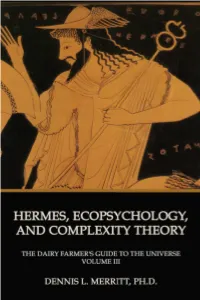

Hermes, Ecopsychology, and Complexity Theory

PSYCHOLOGY / JUNGIAN / ECOPSYCHOLOGY “Man today is painfully aware of the fact that neither his great religions nor his various philosophies seem to provide him with those powerful ideas that would give him the certainty and security he needs in face of the present condition of the world.” —C.G. Jung An exegesis of the myth of Hermes stealing Apollo’s cattle and the story of Hephaestus trapping Aphrodite and Ares in the act are used in The Dairy Farmer’s Guide to the Universe Volume III to set a mythic foundation for Jungian ecopsychology. Hermes, Ecopsychology, and Complexity Theory HERMES, ECOPSYCHOLOGY, AND illustrates Hermes as the archetypal link to our bodies, sexuality, the phallus, the feminine, and the earth. Hermes’ wand is presented as a symbol for COMPLEXITY THEORY ecopsychology. The appendices of this volume develop the argument for the application of complexity theory to key Jungian concepts, displacing classical Jungian constructs problematic to the scientific and academic community. Hermes is described as the god of complexity theory. The front cover is taken from an original photograph by the author of an ancient vase painting depicting Hermes and his wand. DENNIS L. MERRITT, Ph.D., is a Jungian psychoanalyst and ecopsychologist in private practice in Madison and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. A Diplomate of the C.G. Jung Institute of Analytical Psychology, Zurich, Switzerland, he also holds the following degrees: M.A. Humanistic Psychology-Clinical, Sonoma State University, California, Ph.D. Insect Pathology, University of California- Berkeley, M.S. and B.S. in Entomology, University of Wisconsin-Madison. He has participated in Lakota Sioux ceremonies for over twenty-five years which have strongly influenced his worldview. -

Mercury (Mythology) 1 Mercury (Mythology)

Mercury (mythology) 1 Mercury (mythology) Silver statuette of Mercury, a Berthouville treasure. Ancient Roman religion Practices and beliefs Imperial cult · festivals · ludi mystery religions · funerals temples · auspice · sacrifice votum · libation · lectisternium Priesthoods College of Pontiffs · Augur Vestal Virgins · Flamen · Fetial Epulones · Arval Brethren Quindecimviri sacris faciundis Dii Consentes Jupiter · Juno · Neptune · Minerva Mars · Venus · Apollo · Diana Vulcan · Vesta · Mercury · Ceres Mercury (mythology) 2 Other deities Janus · Quirinus · Saturn · Hercules · Faunus · Priapus Liber · Bona Dea · Ops Chthonic deities: Proserpina · Dis Pater · Orcus · Di Manes Domestic and local deities: Lares · Di Penates · Genius Hellenistic deities: Sol Invictus · Magna Mater · Isis · Mithras Deified emperors: Divus Julius · Divus Augustus See also List of Roman deities Related topics Roman mythology Glossary of ancient Roman religion Religion in ancient Greece Etruscan religion Gallo-Roman religion Decline of Hellenistic polytheism Mercury ( /ˈmɜrkjʉri/; Latin: Mercurius listen) was a messenger,[1] and a god of trade, the son of Maia Maiestas and Jupiter in Roman mythology. His name is related to the Latin word merx ("merchandise"; compare merchant, commerce, etc.), mercari (to trade), and merces (wages).[2] In his earliest forms, he appears to have been related to the Etruscan deity Turms, but most of his characteristics and mythology were borrowed from the analogous Greek deity, Hermes. Latin writers rewrote Hermes' myths and substituted his name with that of Mercury. However, there are at least two myths that involve Mercury that are Roman in origin. In Virgil's Aeneid, Mercury reminds Aeneas of his mission to found the city of Rome. In Ovid's Fasti, Mercury is assigned to escort the nymph Larunda to the underworld. -

01 Heitsch-Aufs AK2:Layout 1

THE BABYLONIAN CAPTIVITY OF HOMER: THE CASE OF THE ΔΙΟΣ ΑΠΑΤΗ* The Δι ς πτη or ‘Deception of Zeus’ in the Iliad’s 14th and 15th books (DA hereafter) was subject to an intense and varied scrutiny in the ancient period – moralising, disapproving, allegor- ical.1 Though these judgements have found adherents as well as op- ponents in modern scholarship,2 by far the most influential recent interpretations have been conducted from an ‘orientalising’ per- spective, documenting the links between Greece and the other civilisations of the Mediterranean basin.3 Features in the DA which *) I would like to thank Bill Allan, Patrick Finglass, Sophie Gibson, Antonia Karaisl, Bernd Manuwald, Oliver Taplin, Stephan Schröder, Alan Sommerstein, and audiences in Nottingham, Oxford and Berlin for their help with this article and its material, and the Institut für Klassische Philologie der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and the Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung for their support. The remaining faults are my responsibility alone. 1) The title is strictly applied in ancient sources to the 14th book (Eustathios 963.22–5 [565 van der Valk]; cf. also Σ L ad Il. 14.135) but, for reasons which will become clear, it has come to be used also for the episode’s sequel in the 15th book. For ancient commentary on the DA, cf., e. g., Plato, Rep. 3.390b–c; Eustathios 973.56f. ad Il. 14.161–324 (598–9 van der Valk). For a review of modern opinions on the scene, cf. M. Schäfer, Der Götterstreit in der Ilias (Stuttgart 1990) 87–9, nn. -

Memory and Performance: Strategies of Identity in the Orphic-Bacchic Lamellae by Mark Frederick Mcclay

Memory and Performance: Strategies of Identity in the Orphic-Bacchic Lamellae By Mark Frederick McClay A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Professor Nikolaos Papazarkadas Professor James I. Porter Fall 2018 Copyright 2018, Mark Frederick McClay Abstract Memory and Performance: Strategies of Identity in the Orphic-Bacchic Lamellae by Mark Frederick McClay Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Griffith, Chair This dissertation is a treatment of the Orphic-Bacchic lamellae, a collection of small gold tablets that were deposited in the graves of Dionysiac mystery initiates, mostly during the 4th/3rd c. BCE. So far, thirty-eight of these have been discovered, from various sites in Sicily, Magna Graecia, Northern Greece, Crete, and the Peloponnese. The tablets were deposited in the graves of both men and women, and they are inscribed with short poetic texts, mostly in hexameters, that offer promises of postmortem happiness. Scholarship on these objects has traditionally focused on the sacral and eschatological language of the texts and their underlying doctrinal structure. Past interpretations, and discussions of “Orphism” more generally, have relied on propositional definitions of “religion” that are centered on belief and on the scriptural authority of sacred texts rather than ritual or sensory experience. Following recent critiques of these models in general (and of their application to Orphic phenomena in particular), I consider the gold leaves in their social context as objects produced, handled, and disseminated by ritual performers. -

The World of Greek Religion and Mythology

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament Herausgeber/Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber/Associate Editors Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) ∙ James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Tobias Nicklas (Regensburg) ∙ Janet Spittler (Charlottesville, VA) J. Ross Wagner (Durham, NC) 433 Jan N. Bremmer The World of Greek Religion and Mythology Collected Essays II Mohr Siebeck Jan N. Bremmer, born 1944; Emeritus Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Groningen. orcid.org/0000-0001-8400-7143 ISBN 978-3-16-154451-4 / eISBN 978-3-16-158949-2 DOI 10.1628/978-3-16-158949-2 ISSN 0512-1604 / eISSN 2568-7476 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiblio- graphie; detailed bibliographic data are available at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen, Germany. www.mohrsiebeck.com This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitt- ed by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particular- ly to reproductions, translations and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset using Stempel Garamond typeface and printed on non-aging pa- per by Gulde Druck in Tübingen. It was bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. in memoriam Walter Burkert (1931–2015) Albert Henrichs (1942–2017) Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood (1945–2007) Preface It is a pleasure for me to offer here the second volume of my Collected Essays, containing a sizable part of my writings on Greek religion and mythology.1 Greek religion is not a subject that has always held my interest and attention.