Chapman Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Travails of the Working-Class Auction Bidder

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication College of Communication 2015 “Get Rich or Die Buying:” The Travails of the Working-Class Auction Bidder Mark A. Rademacher Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rademacher, Mark A., "“Get Rich or Die Buying:” The Travails of the Working-Class Auction Bidder" (2015). Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication. 100. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers/100 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Communication at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Get Rich or Die Buying:” The Travails of the Working-Class Auction Bidder Mark A. Rademacher These are the rules of storage auctions. This is a cash only sale. All sales are final. We're gonna cut the lock. We're gonna open the door. You're gonna have five minutes to look. You cannot go inside the unit, you cannot open any boxes. We are gonna sell this to the highest cash bidder. Are you ready to go? Dan Dotson, Storage Wars Auctioneer (“High Noon in the High Desert”) With these basic rules, auctioneer Dan Dotson sets the stage for the drama that unfolds during A&E Network's popular reality TV (RTV) program Storage Wars (2010–). -

PAX CENTURION • September/October 2015 617-989-BPPA (2772) a Message from the President: Patrick M

New BPPA Headquarters Takes Shape pages 12 & 13 PAXCENTURION The Newsmagazine for the Boston Police Patrolmen’s Association Celebrating 50 Years See pages 16-22 September/October 2015 Burke Distributing has serviced Boston since 1935 & proudly supports the Boston Police Patrolmen’s Association 89 Teed Dr. Randolph, MA 02368 www.burkedist.com Page 2 • PAX CENTURION • September/October 2015 617-989-BPPA (2772) A Message from the President: Patrick M. Rose, BPPA President 50 years ago, eleven brave men made history and founded the BPPA ifty (50) years ago, eleven (11) very brave men sat in a ly promised we will be conducting ‘Open Meetings’ more often with cramped kitchen at 193 & 1/2 Fairmont Avenue and decided to the next one scheduled for January 6, 2016 at 5:00 pm, (in order to Ftempt fate by placing their signatures on a document declar- accommodate different shifts). We are well underway with the minor ing the founding of ‘The Boston Police Patrolmen’s Association’, renovations and updates to the office area of the new hall so that we Our founders were actually willing to put their careers and weekly can move the day-to-day Union operation in as soon as possible. We paychecks on the line for the good of all. I would be remiss if I didn’t have been extremely fortunate in receiving many unsolicited offers put in print the names of my predecessors over the last fifty years: for our present property at 9-11 Shetland Street and believe there will Dick MacEachern (our Founder), Dan Sweeney, Chet Broder- be no problem in disposing of that property in the future, benefit- ick, Bobby Guiney, Don Murray, Dick Bradley and Tom Nee. -

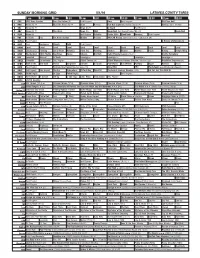

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch Relationship in the United States

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch relationship in the United States When Donald Trump ran as a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, Rupert Murdoch was reported to be initially opposed to him, so the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post were too.1 However, Roger Ailes and Murdoch fell out because Ailes wanted to give more positive coverage to Trump on Fox News.2 Soon afterwards, however, Fox News turned more negative towards Trump.3 As Trump emerged as the inevitable winner of the race for the nomination, Murdoch’s attitude towards Trump appeared to shift, as did his US news outlets.4 Once Trump became the nominee, he and Rupert Murdoch effectively concluded an alliance of mutual benefit: Murdoch’s news outlets would help get Trump elected, and then Trump would use his powers as president in ways that supported Rupert Murdoch’s interests. An early signal of this coming together was Trump’s public attacks on the AT&T-Time Warner merger, 21st Century Fox having tried but failed to acquire Time Warner previously in 2014. Over the last year and a half, Fox News has been the major TV news supporter of Donald Trump. Its coverage has displayed extreme bias in his favour, offering fawning coverage of his actions and downplaying or rubbishing news stories damaging to him, while also leading attacks against Donald Trump’s opponent in the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton. Ofcom itself ruled that several Sean Hannity programmes in August 2016 were so biased in favour of Donald Trump and against Hillary Clinton that they breached UK impartiality rules.5 During this period, Rupert Murdoch has been CEO of Fox News, in which position he is also 1 See e.g. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Le Groupe M6 a Choisi Metro Goldwyn Mayer Et Mark Burnett Pour Signer Un Accord D'exploitation Du Format « Audition Secrète

Le Groupe M6 a choisi Metro Goldwyn Mayer et Mark Burnett pour signer un accord d’exploitation du format « Audition Secrète », produit par Studio 89 d’après le format « Secret Audition » détenu par Studio 89, Explay Music et La Casa. Cet accord intervient pour une exploitation dans 12 territoires : Les Etats-Unis, le Canada, l’Australie, UK, Pays-Bas, Espagne, Italie, Norvège, Suède, Finlande, Danemark et Inde. Diffusé sur la chaîne M6 à partir du 24 juillet, « Audition Secrète » (Secret Audition) est un divertissement inédit qui permet de découvrir de nouveaux talents en plaçant les proches au cœur du dispositif. Le lancement de l’émission a rencontré un vif succès auprès des téléspectateurs, permettant à M6 de se classer leader auprès des moins de 50 ans et en particulier sur la cible commerciale (25% auprès des FRDA-50). Cet accord positionne Studio 89, l’unité des flux internes du Groupe M6, comme un nouvel acteur sur le marché de la vente de formats. Son programme « Chasseurs d’Appart » (Flat Hunters), a déjà été adapté dans 5 territoires. Le concept d'« Audition Secrète » Des producteurs de maison de disque sont persuadés que de nombreux chanteurs anonymes n'ont pas osé se dévoiler : soit parce qu'ils ont peur, soit parce que la vie les a poussés à faire d'autres choix, ou encore parce qu'ils n'imaginent pas avoir suffisamment de talent. Puisque ces talents ne veulent pas sortir de l'ombre, des producteurs reconnus ont imaginé un stratagème inédit pour les propulser dans la lumière. Grâce à la complicité de leurs proches, ces talents vont se retrouver sur scène sans le savoir ! L'effet de surprise passé, ils auront alors la possibilité, s'ils le souhaitent, de montrer à tous ce talent de chanteur qu'ils gardaient caché jusque-là. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

THE VOICE Feb 4, 2004 Volume 12, Issue 05

THE VOICE Feb 4, 2004 Volume 12, Issue 05 Welcome To The Voice PDF he Voice has an interactive table of contents. Click on a story title or author name to jump to an article. Click the T bottom-right corner of any page to return to the contents. Some ads and graphics are also links. FEATURES EDITORIAL PAGES ARTICLES NATURE NOTES - FAUNAL ADAPTATIONS Zoe Dalton REMEMBERING A LESS THAN PERFECT MOTHER Barbara Godin IS THERE A DOULA IN THE HOUSE - pt 2 Sara Kinninmont FMP: FREEDOM OF SPEECH Debbie Jabbour THE GLEASON BROTHERS Wayne E. Benedict FICTION FEATURE POETRY BY… Bill Pollett COLUMNS SOUNDING OFF - Commercials we hate; toughest AU courses PRIMETIME UPDATE Amanda Lyn Baldwin NEW: DEAR HEATHER TAKING NOTES: EYE ON EDUCATION Debbie Jabbour CANADIAN FEDWATCH! Karl Low AUSU THIS MONTH FLICKS & FOLIOS: Weekend at Bernies Laura Seymour NEWS AND ANNOUNCEMENTS VOICE EVENTS LISTINGS SCHOLARSHIPS AND AWARDS CONFERENCE CONNECTIONS The Insider FROM THE READERS LETTERS TO THE EDITOR CLASSIFIEDS! THE VOICE c/o Athabasca University Students' Union We love to hear from you! Send your questions and 2nd Floor, 10030-107th Street, comments to [email protected], and please indicate if we may Edmonton, AB T5J 3E4 publish your letter in the Voice. 800.788.9041 ext. 3413 Publisher Athabasca University Students' Union Editor In Chief Tamra Ross Low Response to Shannon Maguire's "Where Has All The Fat News Contributor Lonita Fraser Come From", v12 i04, January 28, 2004. I really appreciate Shannon's comments, but, and perhaps it's just THE VOICE ONLINE: the psychology student in me, why does everyone seem to ignore WWW.AUSU.ORG/VOICE the mental and emotional baggage involved in weight loss? I have repeatedly been uncomfortable with the prospect of being slim due to an asinine inner belief that I will be attacked by crazed The Voice is published every men .. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047

t. OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code 2006 (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation ) Open to Department of the Treasury Public Inspection Internal Revenue Service ► The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements A For the 2006 calendar year, or tax year beginning , 2006 , and ending , B Check if applicable C Name of organization D Employer Identification Number Address change IRSlabele NAVAL SPECIAL WAREFARE FOUNDATION 31-1728910 or print Name change ortype. Number and street (or P 0 box if mail is not delivered to street addr) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial return spe cfi ic P.O.BOX 5965 (757) 363-7490 mstruc- town or State ZIP code + 4 F meth.atm g Final return tions . City , countrYry metho Cash X Accrual Amended return VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23471-0965 Other (specify) ll^ q Application pending • Section 501 (cx3) organizations and 4947(aXl) nonexempt H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations charitable trusts must attach a completed Schedule A H (a) Is this a group return for affiliates ' q Yes No (Form 990 or 990-EZ). H (b) If 'Yes ,' enter number of affiliates G Web site: 11, nswfoundation. or g H (c) Are all affiliates included? q Yes q No (If 'No,' attach a list See instructions J Organization type ) q q (check only one ► 501(c) 3 ' (insert no) 4947(a)(1) or 527 H (d) Is this a separate return filed by an organization covered by a group ruling' K Check here if the organization is not a 509(a)(3) supporting organization and its 11 Yes FX] gross receipts are normally not more than $25,000 A return is not required, but if the I Grou p Exem ption Number 110- organization chooses to file a return, be sure to file a complete return. -

March 2013 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data

March 2013 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data March 3, 2013 25 men and 10 women NBC's Meet the Press with David Gregory: 5 men and 2 women Speaker of the House John Boehner (M) Gene Sperling (M) Rep. Raul Labrador (M) Kathleen Parker (F) Joy Reid (F) Chuck Todd (M) Tom Brokaw (M) CBS's Face the Nation with Bob Schieffer: 7 men and 1 woman Sen. Lindsey Graham (M) Sen. John McCain (M) Sen. Majority Whip Dick Durbin (M) Cardinal Timothy Dolan (M) Bob Woodward (M) David Sanger (M) Rana Foroohar (F) John Dickerson (M) ABC's This Week with George Stephanopoulos: 4 men and 3 women Gene Sperling (M) Sen. Kelly Ayotte (F) James Carville (M) Matthew Dowd (M) Paul Gigot (M) Mayor Mia Love (F) Cokie Roberts (F) CNN's State of the Union with Candy Crowley: 6 men and 1 woman Sen. Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (M) Gene Sperling (M) Rep. Steve Israel (M) Rep. Greg Walden (M) Mark Zandi (M) Stephen Moore (M) Susan Page (F) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: 3 men and 3 women Fmr. Gov. Mitt Romney (M) Ann Romney (F) Bill Kristol (M) Kirsten Powers (F) Fmr. Sen. Scott Brown (F) Charles Lane (M) March 10, 2013 25 men and 13 women NBC's Meet the Press with David Gregory: 6 men and 3 women Sen. Tim Kaine (M) Sen. Tom Coburn (M) Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (F) Rep. Cory Garnder (M) Joe Scarborough (M) Dee Dee Myers (F) Rep. Marsha Blackburn (F) Steve Schmidt (M) Ruth Marcus (F) Fmr. -

Ex Parte Vallandigham

U.S. Ex Parte Vallandigham 68 U.S. 243 (1863) Decided Jan 1, 1863 DECEMBER TERM, 1863. The Supreme Court of the United States has no power to review by certiorari the proceedings of a military commission ordered by a general officer of the United States Army, commanding a military department. THIS case arose on the petition of Clement L. Vallandigham for a certiorari, to be directed to the Judge Advocate General of the Army of the United States, to send up to this court, for its review, the proceedings of a military commission, by which the said Vallandigham had been tried and sentenced to imprisonment; the facts of the case, as derived from the statement of the learned Justice (WAYNE) who delivered the opinion of the court, having been as follows: Major-General Burnside, commanding the military department of Ohio, issued a special order, No. 135, on the 21st April, 1863, by which a military commission was appointed to meet at Cincinnati, Ohio, on the 22d of April, or as soon thereafter as practicable, for the trial of such persons as might be brought before it. There was a detail of officers to constitute it, and a judge advocate appointed. The same general had, previously, on the 13th of April, 1863, issued a general order, No. 38, declaring, for the 244 information of all persons concerned, that thereafter all persons *244 found within his lines who should commit acts for the benefit of the enemies of our country, should be tried as spies or traitors, and if convicted should suffer death; and among other acts prohibited, was the habit of declaring sympathies for the enemy. -

Oral History Interview of James Hennigan, Jr

Oral History Interview of James Hennigan, Jr. (OH-066) Moakley Archive and Institute www.suffolk.edu/moakley [email protected] Oral History Interview of James Hennigan, Jr. (OH-066) Interview Date: January 19, 2007 Interviewed by: Robert Allison, Suffolk University History Professor, and Joseph McEttrick, Suffolk University Law School Professor. Citation: Hennigan, Jr., James W. Interviewed by Robert Allison and Joseph McEttrick. John Joseph Moakley Oral History Project OH-066. 19 January 2007. Transcript and audio available. John Joseph Moakley Archive and Institute, Suffolk University, Boston, MA. Copyright Information: Copyright ©2007 Suffolk University. Interview Summary In this interview, James W. Hennigan, Jr., a Suffolk University Law School alumnus (JD 1958), Massachusetts state representative (1953-1954), state senator (1955-1964), and Boston School Committee member (1970-1974), discusses the impact of the 1974 Garrity decision, which required some students to be bused between Boston neighborhoods with the intention of creating racial balance in the public schools. Mr. Hennigan reflects on the issue of busing in the Boston Public School system, recalling the Boston School Committee’s work in the years prior to the Garrity decision and the roles which various politicians and city leaders played in the debate. He reminisces about Boston’s great politicians. Additionally, he recalls his memories of Joe Moakley’s successful run as an Independent candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1972. Mr. Hennigan also shares a bit of his political career and that of his family. Page 1 of 33 Oral History Interview of James Hennigan, Jr. (OH-066) Moakley Archive and Institute www.suffolk.edu/moakley [email protected] Subject Headings Boston (Mass.).