Bells Across the Land 2015 Park Resource Packet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Confederate Veterans Association Records

UNITED CONFEDERATE VETERANS ASSOCIATION RECORDS (Mss. 1357) Inventory Compiled by Luana Henderson 1996 Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana Revised 2009 UNITED CONFEDERATE VETERANS ASSOCIATION RECORDS Mss. 1357 1861-1944 Special Collections, LSU Libraries CONTENTS OF INVENTORY SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL NOTE ...................................................................................... 4 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF SUBGROUPS AND SERIES ......................................................................................... 7 SUBGROUPS AND SERIES DESCRIPTIONS ............................................................................ 8 INDEX TERMS ............................................................................................................................ 13 CONTAINER LIST ...................................................................................................................... 15 APPENDIX A ............................................................................................................................... 22 APPENDIX B ............................................................................................................................. -

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

Appomattox Court House Is on the Crest of a 770-Foot High Ridge

NFS Form 1MOO OWB No. 1024-O01S United States Department of the Interior National Park Service I 9 /98g National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name APPnMATTnY rnriPT unn^F other names/site number APPOM ATTnY ^HITBT HHTTC;P MATTDMAT HISTOPICAT. PARK 2. Location , : _ | not for publication street & nurnberAPPOMATTOX COUPT" HOUSE NATIONAL HISTO RICAL PAR city, town APPOMATTOX v| vicinity code " ~ "* state TrrnrrxTTA code CH county APPnMATTnY Q I T_ zip code 2^579 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property a private n building(s) Contributing Noncontributing public-local B district 31 3 buildings 1 1 public-State site Q sites f_xl public-Federal 1 1 structure lit 1 fl structures CH object 1 objects Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously None_________ listed in the National Register 0_____ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification Asjhe designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this Sd nomination I I request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

List of Staff Officers of the Confederate States Army. 1861-1865

QJurttell itttiuetsity Hibrary Stliaca, xV'cni tUu-k THE JAMES VERNER SCAIFE COLLECTION CIVIL WAR LITERATURE THE GIFT OF JAMES VERNER SCAIFE CLASS OF 1889 1919 Cornell University Library E545 .U58 List of staff officers of the Confederat 3 1924 030 921 096 olin The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924030921096 LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES ARMY 1861-1865. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1891. LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE ARMY. Abercrombie, R. S., lieut., A. D. C. to Gen. J. H. Olanton, November 16, 1863. Abercrombie, Wiley, lieut., A. D. C. to Brig. Gen. S. G. French, August 11, 1864. Abernathy, John T., special volunteer commissary in department com- manded by Brig. Gen. G. J. Pillow, November 22, 1861. Abrams, W. D., capt., I. F. T. to Lieut. Gen. Lee, June 11, 1864. Adair, Walter T., surg. 2d Cherokee Begt., staff of Col. Wm. P. Adair. Adams, , lieut., to Gen. Gauo, 1862. Adams, B. C, capt., A. G. S., April 27, 1862; maj., 0. S., staff General Bodes, July, 1863 ; ordered to report to Lieut. Col. R. G. Cole, June 15, 1864. Adams, C, lieut., O. O. to Gen. R. V. Richardson, March, 1864. Adams, Carter, maj., C. S., staff Gen. Bryan Grimes, 1865. Adams, Charles W., col., A. I. G. to Maj. Gen. T. C. Hiudman, Octo- ber 6, 1862, to March 4, 1863. Adams, James M., capt., A. -

Qfwar'slastdays ."St Fighting

Only Newspaper in North Carolina That Has Over 10,000 Subscribers. 16 Pages—Section One—Pages i to 8, The News and Observer. Volume LVII. No. 28. RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA, TUESDAY MORNING, APRIL 11. 1905. Price Five Cents. sqDD fcipftflD ©sqtoDßod® Papstps Bod GB®{tOD Kl®w© sqodgO (EB[p©QoOs]tiO®QD spring opened it became daily more my skirmishers and it(iffabf apparent that human power and en- battle. I reconnoiter durance could do no more, and that AN myself as to their position?»- <• jq APPOMATTOX VETERAN J a forced evacuation of the beleaguered ed the arrivel of General Gorao,. FUTILE MEET city was near at hand. In anticipation instructions, who, a wiiile before day, ."ST FIGHTING of ~that event General Lee caused the accompanied by General Fitz Lee, removal of all his surplus material to TELLS OF CLOSING SCENES came to my position, when we held a Amelia Court House.” “While his ad- council of war. General Gordon was versary was thus active, Lee was not of the opinion that the troops in our QF WAR'S LAST DAYS idle. He had formed a plan to sur- front were cavalry, and that General BY 'TAR HEELS prise the enemy’s centre by a night Major H. A. London Reviews the Claims of North Fitz Lee should attack. Fitz Lee attack, which, if succes.sful, would thought they were infantry and that would have given him possession of Carolina, and Cites the Evidence, Speaking General Gordon should attack. They Capt. S. A. a commanding position in the enemy’s discussed the matter so long that I Captain Jenkins Tells of Ashe Recounts rear, and control of the military rail- became impatient, and said it was road to City Point, a very important as Eye-Witness of Last Act of Drama. -

The Americans

INTERACT WITH HISTORY The year is 1861. Seven Southern states have seceded from the Union over the issues of slavery and states rights. They have formed their own government, called the Confederacy, and raised an army. In March, the Confederate army attacks and seizes Fort Sumter, a Union stronghold in South Carolina. President Lincoln responds by issuing a call for volun- teers to serve in the Union army. Can the use of force preserve a nation? Examine the Issues • Can diplomacy prevent a war between the states? • What makes a civil war different from a foreign war? • How might a civil war affect society and the U.S. economy? RESEARCH LINKS CLASSZONE.COM Visit the Chapter 11 links for more information about The Civil War. 1864 The 1865 Lee surrenders to Grant Confederate vessel 1864 at Appomattox. Hunley makes Abraham the first successful Lincoln is 1865 Andrew Johnson becomes submarine attack in history. reelected. president after Lincoln’s assassination. 1863 1864 1865 1864 Leo Tolstoy 1865 Joseph Lister writes War and pioneers antiseptic Peace. surgery. The Civil War 337 The Civil War Begins MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW Terms & Names The secession of Southern The nation’s identity was •Fort Sumter •Shiloh states caused the North and forged in part by the Civil War. •Anaconda plan •David G. Farragut the South to take up arms. •Bull Run •Monitor •Stonewall •Merrimack Jackson •Robert E. Lee •George McClellan •Antietam •Ulysses S. Grant One American's Story On April 18, 1861, the federal supply ship Baltic dropped anchor off the coast of New Jersey. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, som e thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of com puter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI EDWTN BOOTH .\ND THE THEATRE OF REDEMPTION: AN EXPLORATION OF THE EFFECTS OF JOHN WTLKES BOOTH'S ASSASSINATION OF ABRAHANI LINCOLN ON EDWIN BOOTH'S ACTING STYLE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael L. -

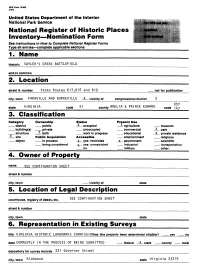

National Register Off Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1. Name___2. Location___3. Classifica

NFS Form 10-900 (7-81) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register off Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name_________________ historic SAYLER'S CREEK BATTLEFIELD_________________ and/or common____________________________________ 2. Location______________ street & number State Routes 617,618 and 619 not for publication city, town FARMVILLE AND BURKEVILLE _X_ vicinity of congressional district 007 state VIRGINIA code 51 county AMELIA & PRINCE EDWARD code 147 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use __ district __ public _X_ occupied _X. agriculture museum __ building(s) __ private __ unoccupied __ commercial x park __ structure _1L both __ work in progress __ educational X private residence _X_site Public Acquisition Accessible __ entertainment __ religious __ object __ in process X yes: restricted government __ scientific __ being considered yes: unrestricted industrial __ transportation no military __ other: 4. Owner off Property name SEE CONTINUATION SHEET street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. SEE CONTINUATION SHEET street & number city, town state 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title VIRGINIA HI STORIC LANDMARKS COMMI SS I ONias this property been determined eligible? yes no date CURRENTLY IN THE PROCESS OF BEING SUBMITTED federal X state county local depository for survey records 221 Governor Street city, town Richmond state Virginia 23219 7. Description Condition Check one Check one X excellent deteriorated X unaltered X original s ite good .. ruins altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance I. -

The Lincoln Assassination

The Lincoln Assassination The Civil War had not been going well for the Confederate States of America for some time. John Wilkes Booth, a well know Maryland actor, was upset by this because he was a Confederate sympathizer. He gathered a group of friends and hatched a devious plan as early as March 1865, while staying at the boarding house of a woman named Mary Surratt. Upon the group learning that Lincoln was to attend Laura Keene’s acclaimed performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, Booth revised his mastermind plan. However it still included the simultaneous assassination of Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. By murdering the President and two of his possible successors, Booth and his co-conspirators hoped to throw the U.S. government into disarray. John Wilkes Booth had acted in several performances at Ford’s Theatre. He knew the layout of the theatre and the backstage exits. Booth was the ideal assassin in this location. Vice President Andrew Johnson was at a local hotel that night and Secretary of State William Seward was at home, ill and recovering from an injury. Both locations had been scouted and the plan was ready to be put into action. Lincoln occupied a private box above the stage with his wife Mary; a young army officer named Henry Rathbone; and Rathbone’s fiancé, Clara Harris, the daughter of a New York Senator. The Lincolns arrived late for the comedy, but the President was reportedly in a fine mood and laughed heartily during the production. -

Abraham Lincoln Official Bicentennial Publication State Participation: Virginia

Abraham Lincoln official Bicentennial Publication State Participation: Virginia 1. Name of state: Virginia 2. State motto: "Sic Semper Tyrannis" (Thus Always to Tyrants) 3. Governor's message: On behalf of the citizens of the Commonwealth of Virginia, I am honored to pay tribute to one of America’s greatest leaders. Our nation’s proud history serves as an enduring testament to the fortitude and resolve of Abraham Lincoln. The experiment of American democracy faced a vital test as Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office as its sixteenth president. No American leader since Virginia’s own George Washington had taken the helm of the United States with such a challenge, as Lincoln would phrase it: such a “house divided.” Yet as his term and his brief life came to a close, Lincoln wiped the injustice of slavery from American society, restored the Union and brought us one step closer to the realization of the ideals upon which the country was founded. Although Lincoln is a son of Illinois, we in Virginia claim him as a brother. Lincoln has extensive family ties to the Commonwealth – his great-grandparents and grandparents lived in Virginia and his parents met, married, and lived for a time in the Shenandoah Valley. In Virginia, we claim Lincoln as a brother not just because his roots here run deep. Throughout his life, Lincoln exhibited the best qualities of Virginians. He embodied the courage of the Jamestown settlers and of two of his predecessors, Washington and Jefferson. Lincoln devoted himself to breaking the bonds that divided communities and his influence echoed in the twentieth century through the life of legal pioneer Oliver Hill. -

Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr

Copyright © 2013 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation i Table of Contents Letter from Erin Carlson Mast, Executive Director, President Lincoln’s Cottage Letter from Martin R. Castro, Chairman of The United States Commission on Civil Rights About President Lincoln’s Cottage, The National Trust for Historic Preservation, and The United States Commission on Civil Rights Author Biographies Acknowledgements 1. A Good Sleep or a Bad Nightmare: Tossing and Turning Over the Memory of Emancipation Dr. David Blight……….…………………………………………………………….….1 2. Abraham Lincoln: Reluctant Emancipator? Dr. Michael Burlingame……………………………………………………………….…9 3. The Lessons of Emancipation in the Fight Against Modern Slavery Ambassador Luis CdeBaca………………………………….…………………………...15 4. Views of Emancipation through the Eyes of the Enslaved Dr. Spencer Crew…………………………………………….………………………..19 5. Lincoln’s “Paramount Object” Dr. Joseph R. Fornieri……………………….…………………..……………………..25 6. Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr. Allen Carl Guelzo……………..……………………………….…………………..31 7. Emancipation and its Complex Legacy as the Work of Many Hands Dr. Chandra Manning…………………………………………………..……………...41 8. The Emancipation Proclamation at 150 Dr. Edna Greene Medford………………………………….……….…….……………48 9. Lincoln, Emancipation, and the New Birth of Freedom: On Remaining a Constitutional People Dr. Lucas E. Morel…………………………….…………………….……….………..53 10. Emancipation Moments Dr. Matthew Pinsker………………….……………………………….………….……59 11. “Knock[ing] the Bottom Out of Slavery” and Desegregation: -

Ford's Theatre, Lincoln's Assassination and Its Aftermath

Narrative Section of a Successful Proposal The attached document contains the narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful proposal may be crafted. Every successful proposal is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the program guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/education/landmarks-american-history- and-culture-workshops-school-teachers for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Education Programs staff well before a grant deadline. The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: The Seat of War and Peace: The Lincoln Assassination and Its Legacy in the Nation’s Capital Institution: Ford’s Theatre Project Directors: Sarah Jencks and David McKenzie Grant Program: Landmarks of American History and Culture Workshops 400 7th Street, S.W., 4th Floor, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8500 F 202.606.8394 E [email protected] www.neh.gov 2. Narrative Description 2015 will mark the 150th anniversary of the first assassination of a president—that of President Abraham Lincoln as he watched the play Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre, six blocks from the White House in Washington, D.C.