ISG News 5(1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyclura Or Rock Iguanas Cyclura Spp

Cyclura or Rock Iguanas Cyclura spp. There are 8 species and 16 subspecies of Cyclura that are thought to exist today. All Cyclura species are endangered and are listed as CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) Appendix I, the highest level of pro- tection the Convention gives. Wild Cyclura are only found in the Caribbean, with many subspecies endemic to only one particular island in the West Indies. Cyclura mature and grow slowly compared to other lizards in the family Iguani- dae, and have a very long life span (sometimes reaches ages of 50+ years). The more common species in the pet trade in- clude the Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta cornuta), and Cuban Rock Iguana (juvenile), the Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila nubila). Cyclura nubila nubila Basic Care: Habitat: Cyclura care is similar to that of the Green Iguana (Iguana iguana), but there are some major differences. Cyclura Iguanas are generally ground-dwelling lizards, and require a very large cage with lots of floor space. The suggested minimum space to keep one or two adult Cyclura in captivity is usually a cage that is at the very least 10’X10’. Because of this space requirement, many cyclura owners choose to simply des- ignate a room of their home to free-roaming. If a male/female pair are to be kept to- gether, multiple basking spots, feeding stations, and hides will be required. All Cyclura are extremely territorial and can inflict serious injuries or even death to their cage- mates unless monitored carefully. The recommended temperature for Cyclura is a basking spot of about 95-100F during the day, with a temperature gradient of cooler areas to escape the heat. -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

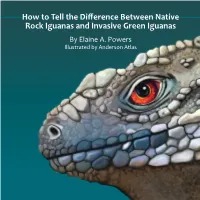

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

ISG News 9(1).Indd

Iguana Specialist Group Newsletter Volume 9 • Number 1 • Summer 2006 The Iguana Specialist Group News & Comments prioritizes and facilitates conservation, science, and onservation Centers for Species Survival Formed j Cyclura spp. were awareness programs that help Cselected as a taxa of mutual concern under a new agreement between a select ensure the survival of wild group of American zoos and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The zoos - under iguanas and their habitats. the banner of Conservation Centers for Species Survival (C2S2) - and USFWS have pledged to work cooperatively to advance conservation of the selected spe- cies by identifying specific research projects, actions, and opportunities that will significantly and clearly support conservation efforts. Cyclura are the only lizards selected under the joint program. The zoos participating in the program include the San Diego Wild Animal Park, Fossil Rim Wildlife Center, The Wilds, White Oak Conservation Center and the National Zoo’s Conservation and Research Center. USFWS participation will be coordinated by Bruce Weissgold in the Division of Management Authority (bruce_weissgold @fws.gov). IN THIS ISSUE News & Comments ............... 1 RCC Facility at Fort Worth j The Fort Worth Zoo recently opened their Animal Outreach and Conservation Center (ARCC) in an off-exhibit Iguanas in the News ............... 3 A area of the zoo. The $1 million facility actually consists of three separate units. Taxon Reports ...................... 7 The primary facility houses the zoo’s outreach collection, while a state-of-the-art B. vitiensis ...................... 7 reptile conservation greenhouse will highlight the zoo’s work with endangered C. pinguis ..................... 9 iguanas and chelonians. -

RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura Cornuta Cornuta (Bonnaterre 1789)

HUSBANDRY GUIDELINES: RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura cornuta cornuta (Bonnaterre 1789) REPTILIA: IGUANIDAE Compiler: Cameron Candy Date of Preparation: DECEMBER, 2009 Institute: Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond, NSW, Australia Course Name/Number: Certificate III in Captive Animals - 1068 Lecturers: Graeme Phipps - Jackie Salkeld - Brad Walker Husbandry Guidelines: C. c. cornuta 1 ©2009 Cameron Candy OHS WARNING RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura c. cornuta RISK CLASSIFICATION: INNOCUOUS NOTE: Adult C. c. cornuta can be reclassified as a relatively HAZARDOUS species on an individual basis. This may include breeding or territorial animals. POTENTIAL PHYSICAL HAZARDS: Bites, scratches, tail-whips: Rhinoceros Iguanas will defend themselves when threatened using bites, scratches and whipping with the tail. Generally innocuous, however, bites from adults can be severe resulting in deep lacerations. RISK MANAGEMENT: To reduce the risk of injury from these lizards the following steps should be followed: - Keep animal away from face and eyes at all times - Use of correct PPE such as thick gloves and employing correct and safe handling techniques when close contact is required. Conditioning animals to handling is also generally beneficial. - Collection Management; If breeding is not desired institutions can house all female or all male groups to reduce aggression - If aggressive animals are maintained protective instrument such as a broom can be used to deflect an attack OTHER HAZARDS: Zoonosis: Rhinoceros Iguanas can potentially carry the bacteria Salmonella on the surface of the skin. It can be passed to humans through contact with infected faeces or from scratches. Infection is most likely to occur when cleaning the enclosure. RISK MANAGEMENT: To reduce the risk of infection from these lizards the following steps should be followed: - ALWAYS wash hands with an antiseptic solution and maintain the highest standards of hygiene - It is also advisable that Tetanus vaccination is up to date in the event of a severe bite or scratch Husbandry Guidelines: C. -

TERRESTRIAL SPECIES Grand Cayman Blue Iguana Cyclura Lewisi Taxonomy and Range the Grand Cayman Blue Iguana, Cyclura Lewisi, Is

TERRESTRIAL SPECIES Grand Cayman Blue iguana Cyclura lewisi Taxonomy and Range Kingdom: Animalia, Phylum: Chordata, Class: Sauropsida, Order: Squamata, Family: Iguanidae Genus: Cyclura, Species: lewisi The Grand Cayman Blue iguana, Cyclura lewisi, is endemic to the island of Grand Cayman. Closest relatives are Cyclura nubila (Cuba), and Cyclura cychlura (Bahamas); all three having apparently diverged from a common ancestor some three million years ago. Status Distribution: Species endemic to Grand Cayman. Conservation: Critically endangered (IUCN Red List). In 2002 surveys indicated a wild population of 10-25 individuals. By 2005 any young being born into the unmanaged wild population were not surviving to breeding age, making the population functionally extinct. Cyclura lewisi is now the most endangered iguana on Earth. Legal: The Grand Cayman Blue iguana Cyclura lewisi is protected under the Animals Law (1976). Pending legislation, it would be protected under the National Conservation Law (Schedule I). The Department of Environment is the lead body for legal protection. The Blue Iguana Recovery Programme BIRP operates under an exemption to the Animals Law, granted to the National Trust for the Cayman Islands. Natural history While it is likely that the original population included many animals living in coastal shrubland environments, the Blue iguana now only occurs inland, in natural dry shrubland, and along the margins of dry forest. Adults are primarily terrestrial, occupying rock holes and low tree cavities. Younger individuals tend to be more arboreal. Like all Cyclura species the Blue iguana is primarily herbivorous, consuming leaves, flowers and fruits. This diet is very rarely supplemented with insect larvae, crabs, slugs, dead birds and fungi. -

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: IGUANIDAE Cyclura Onchiopsis Cope

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: IGUANIDAE Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Powell, R. 2000. Cyclura onchiopsis. Cyclura onchiopsis Cope Navassa Island Rhinoceros Iguana Metopoceros curnutus: Cope 1866: 124 (part). Cyclura nigerrima Cope 1885: 1006. Nomen nudum. See Re- marks. Cyclura onchiopsis Cope 1885: 1006. Type locality, "from an unknown locality," restricted by Cope (1885 [1886]) to "Navassa Island." Holotype, National Museum of Natural History (USNM) 9977, an adult female, collected July 1878, 0 40 80 120 160 km by H.E. Klotz (examined by author). See Remarks. II.III1'I Cyclura cornuta: Cope 1885 (1886): (part). MAP. Distribution of Cyclura otzchiopsis. The circle represents Navassa Cyclura cornuta nigerrima: Barbour 1937: 132. See Remarks. Island, the type locality and entire range of the species. Cyclura comta onchiopsis: Schwartz and Thomas 1975: 112. See Remarks. Cyclura comuta onchioppsis: Blair 199357. Lapsus. CONTENT. Cyclura onchiopsis is monotypic. DEFINITION. Cyclura onchiopsis is a large Rhinoceros Igua- na in the C. cornuta complex; maximum known SVL of females is 378 mm, of males 420 mm (Schwartz and Carey 1977). Schwartz and Carey (1977) also provided the following descrip- tion (N = 3): "modally 2 rows of scales between the prefrontal shields and the frontal scale. 4 and 6 scale rows between the supraorbital semicircles and the interparietal (no mode), 7 supra- labials to eye center in all specimens, 6 to 10 (no mode) sublabials to eye center, 33 to 38 (i = 36.3) femoral pores, 38 to 41 (r = 38.6) fourth toe subdigital scales, middorsal scales in fifth caudal verticil7 in all specimens, dorsolateral body scales in naris-eye distance 30 to 44, scale rows between rostra1 and nasals 1 or 2; adults as preserved dark and patternless, juveniles unknown." DIAGNOSIS. -

Evolution of the Iguanine Lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) As Determined by Osteological and Myological Characters

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1970-08-01 Evolution of the iguanine lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) as determined by osteological and myological characters David F. Avery Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Life Sciences Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Avery, David F., "Evolution of the iguanine lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) as determined by osteological and myological characters" (1970). Theses and Dissertations. 7618. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/7618 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. EVOLUTIONOF THE IGUA.NINELI'ZiUIDS (SAUR:U1., IGUANIDAE) .s.S DETEH.MTNEDBY OSTEOLOGICJJJAND MYOLOGIC.ALCHARA.C'l'Efi..S A Dissertation Presented to the Department of Zoology Brigham Yeung Uni ver·si ty Jn Pa.rtial Fillf.LLlment of the Eequ:Lr-ements fer the Dz~gree Doctor of Philosophy by David F. Avery August 197U This dissertation, by David F. Avery, is accepted in its present form by the Department of Zoology of Brigham Young University as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 30 l'/_70 ()k ate Typed by Kathleen R. Steed A CKNOWLEDGEHENTS I wish to extend my deepest gratitude to the members of m:r advisory committee, Dr. Wilmer W. Tanner> Dr. Harold J. Bissell, I)r. Glen Moore, and Dr. Joseph R. Murphy, for the, advice and guidance they gave during the course cf this study. -

Molecular Systematics & Evolution of the CTENOSAURA HEMILOPHA

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 9-1999 Molecular Systematics & Evolution of the CTENOSAURA HEMILOPHA Complex (SQUAMATA: IGUANIDAE) Michael Ray Cryder Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Cryder, Michael Ray, "Molecular Systematics & Evolution of the CTENOSAURA HEMILOPHA Complex (SQUAMATA: IGUANIDAE)" (1999). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 613. https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/613 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOMA LINDAUNIVERSITY Graduate School MOLECULARSYSTEMATICS & EVOLUTION OF THECTENOSAURA HEMJLOPHA COMPLEX (SQUAMATA: IGUANIDAE) by Michael Ray Cryder A Thesis in PartialFulfillment of the Requirements forthe Degree Master of Science in Biology September 1999 0 1999 Michael Ray Cryder All Rights Reserved 11 Each person whose signature appears below certifies that this thesis in their opinion is adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree Master of Science. ,Co-Chairperson Ronald L. Carter, Professor of Biology Arc 5 ,Co-Chairperson L. Lee Grismer, Professor of Biology and Herpetology - -/(71— William Hayes, Pr fessor of Biology 111 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to the institution and individuals who helped me complete this study. I am grateful to the Department of Natural Sciences, Lorna Linda University, for scholarship, funding and assistantship. -

Cyclura Rileyi Nuchalis) in the Exuma Islands, the Bahamas

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 11(Monograph 6):139–153. Submitted: 10 September 2014; Accepted: 12 November 2015; Published: 12 June 2016. GROWTH, COLORATION, AND DEMOGRAPHY OF AN INTRODUCED POPULATION OF THE ACKLINS ROCK IGUANA (CYCLURA RILEYI NUCHALIS) IN THE EXUMA ISLANDS, THE BAHAMAS 1,6 2 3 4 JOHN B. IVERSON , GEOFFREY R. SMITH , STESHA A. PASACHNIK , KIRSTEN N. HINES , AND 5 LYNNE PIEPER 1Department of Biology, Earlham College, Richmond, Indiana 47374, USA 2Department of Biology, Denison University, Granville, Ohio 43023, USA 3San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, 15600 San Pasqual Valley Road, Escondido, California 92027, USA 4260 Crandon Boulevard, Suite 32 #190, Key Biscayne, Florida 33149, USA 5Department of Curriculum and Instruction, College of Education, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60607, USA 6Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—In 1973, five Acklins Rock Iguanas (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis) from Fish Cay in the Acklins Islands, The Bahamas, were translocated to Bush Hill Cay in the northern Exuma Islands. That population has flourished, despite the presence of invasive rats, and numbered > 300 individuals by the mid-1990s. We conducted a mark-recapture study of this population from May 2002 through May 2013 to quantify growth, demography, and plasticity in coloration. The iguanas from Bush Hill Cay were shown to reach larger sizes than the source population. Males were larger than females, and mature sizes were reached in approximately four years. Although the sex ratio was balanced in the mid-1990s, it was heavily female-biased throughout our study. Juveniles were rare, presumably due to predation by rats and possibly cannibalism. -

Cyclura Cychlura) in the Exuma Islands, with a Dietary Review of Rock Iguanas (Genus Cyclura)

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 11(Monograph 6):121–138. Submitted: 15 September 2014; Accepted: 12 November 2015; Published: 12 June 2016. FOOD HABITS OF NORTHERN BAHAMIAN ROCK IGUANAS (CYCLURA CYCHLURA) IN THE EXUMA ISLANDS, WITH A DIETARY REVIEW OF ROCK IGUANAS (GENUS CYCLURA) KIRSTEN N. HINES 3109 Grand Ave #619, Coconut Grove, Florida 33133, USA e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—This study examined the natural diet of Northern Bahamian Rock Iguanas (Cyclura cychlura) in the Exuma Islands. The diet of Cyclura cychlura in the Exumas, based on fecal samples (scat), encompassed 74 food items, mainly plants but also animal matter, algae, soil, and rocks. This diet can be characterized overall as diverse. However, within this otherwise broad diet, only nine plant species occurred in more than 5% of the samples, indicating that the iguanas concentrate feeding on a relatively narrow core diet. These nine core foods were widely represented in the samples across years, seasons, and islands. A greater variety of plants were consumed in the dry season than in the wet season. There were significant differences in parts of plants eaten in dry season versus wet season for six of the nine core plants. Animal matter occurred in nearly 7% of samples. Supported by observations of active hunting, this result suggests that consumption of animal matter may be more important than previously appreciated. A synthesis of published information on food habits suggests that these results apply generally to all extant Cyclura species, although differing in composition of core and overall diets. Key Words.—Bahamas; Caribbean; carnivory; diet; herbivory; predation; West Indian Rock Iguanas INTRODUCTION versus food eaten in unaffected areas on the same island, finding differences in both diet and behavior (Hines Northern Bahamian Rock Iguanas (Cyclura cychlura) 2011). -

IT 9.4 B&W Pages

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL IGUANA SOCIETY VOLUME 9, NUMBER 4 uanaWWW IGUANASOCIETY ORG imesECEMBER IIgguana. TTimesD 2002 $6.00 Utila Iguana: A young male Ctenosaura bakeri. Photograph: John Binns Iguana Times 9.4 (b&w) 11/11/02 6:38 AM Page 74 Statement of Purpose The International Iguana Society, Inc. is a not-for-profit corporation dedicated I.I.S. 2002 I.I.S. 2002 to preserving the biological diversity of iguanas. We believe that the best way to protect iguanas and other native plants and animals is to preserve natural Board of Directors Editorial Board habitats and to encourage development of sustainable economies compatible Joseph Wasilewski Allison C. Alberts, PhD with the maintenance of biodiversity. To this end, we will: (1) engage in active President Zoological Society of San Diego conservation, initiating, assisting, and funding conservation efforts in Homestead, FL San Diego, CA cooperation with U.S. and international governmental and private agencies; Robert W. Ehrig Gordon M. Burghardt, PhD (2) promote educational efforts related to the preservation of biodiversity; (3) Founder and Vice President University of Tennessee build connections between individuals and the academic, zoo, and conserva- Big Pine Key, FL Knoxville, TN tion communities, providing conduits for education and for involving the general public in efforts to preserve endangered species; and (4) encourage A. C. Echternacht, PhD Keith Christian, PhD Treasurer the dissemination and exchange of information on the ecology, population Northern Territory University Knoxville, TN Darwin, NT, Australia biology, behavior, captive husbandry, taxonomy, and evolution of iguanas. AJ Gutman John B. Iverson, PhD Secretary and Earlham College Membership Information Membership Coordinator Richmond, IN Iguana Times, the Journal of The International Iguana Society, is distributed West Hartford, CT quarterly to members and member organizations.