Antrocom Journal of Anthropology 12-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tamil Nadu H2

Annexure – H 2 Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships IOCL proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in the State of Tamil Nadu as per following details: Name of location Estimated Minimum Dimension (in Finance to be Fixed Fee / monthly Type of Mode of Security Sl. No Revenue District Type of RO Category M.)/Area of the site (in Sq. arranged by the Minimum Sales Site* Selection Deposit M.). * applicant Bid amount Potential # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 (Regular/Rural) (SC/SC CC (CC/DC/CFS) Frontage Depth Area Estimated Estimated (Draw of Rs. in Lakhs Rs. in 1/SC PH/ST/ST working fund Lots/Bidding) Lakhs CC 1/ST capital required PH/OBC/OBC requireme for CC 1/OBC nt for developme PH/OPEN/OPE operation nt of N CC 1/OPEN of RO Rs. in infrastruct CC 2/OPEN Lakhs ure at RO PH) Rs. in Lakhs 1 Alwarpet Chennai Regular 150 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 2 Andavar Nagar to Choolaimedu, Periyar Pathai Chennai Regular 150 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 3 Anna Nagar Chennai Regular 200 Open CC 20 20 400 25 10 Bidding 30 5 4 Anna Nagar 2nd Avenue Main Road Chennai Regular 200 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 5 Anna Salai, Teynampet Chennai Regular 250 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 6 Arunachalapuram to Besant nagar, Besant ave Road Chennai Regular 150 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 7 Ashok Nagar to Kodambakam power house Chennai Regular 150 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 8 Ashok Pillar to Arumbakkam Metro Chennai Regular 200 Open DC 13 14 182 25 60 Draw of Lots 15 5 9 Ayanavaram -

Metal Craft Heritage of Cauvery and Riverine Regions

Sharada Srinivasan METAL CRAFT HERITAGE OF CAUVERY AND RIVERINE REGIONS NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED STUDIES Bengaluru, India Research Report NIAS/HUM/HSS/U/RR/02/2020 Metal Craft Heritage of Cauvery and Riverine Regions Principal Investigator: Prof Sharada Srinivasan Heritage, Science and Society Programme, NIAS Supported by Tata Consultancy Services HERITAGE, SCIENCE AND SOCIETY PROGRAMMES NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED STUDIES Bengaluru, India 2020 © National Institute of Advanced Studies, 2020 Published by National Institute of Advanced Studies Indian Institute of Science Campus Bengaluru - 560 012 Tel: 2218 5000, Fax: 2218 5028 E-mail: [email protected] NIAS Report: NIAS/HUM/HSS/U/RR/02/2020 ISBN: 978-93-83566-37-2 Typeset & Printed by Aditi Enterprises [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Metal Crafts of the Cauvery region and beyond ..............................................1 2. Chola legacy of icon making of Swamimalai ....................................................4 3. Bell and lamp making in Thanjavur district ....................................................16 4. Swami work: The Art of Thanjavur Plate ........................................................25 5. Copper alloy working centres in Karnataka ....................................................33 6. Iron and Steel Traditions of Telangana Kammari ..........................................37 7. Traditional Blacksmithy of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka ...............................46 8. High-tin bronze metal craft from Aranmula, Kerala .....................................59 -

Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg

Cultural Models Affecting Indian-English 'Matrimonials' and British-English Contact Advertisements with a View to Marriage: A Corpus-based Analysis Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Neuphilologischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg vorgelegt von Sandra Frey 1 Dedicated to my husband and to my parents 1 Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................... 6 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 13 1.1 Aims and Scope ................................................................................................ 14 1.2 Methods and Sources ........................................................................................ 15 1.3 Chapter Outline ................................................................................................ 17 1.4 Previous Scholarship ........................................................................................ 18 2 Matrimonials as a Text Type ................................................................................ 21 2.1 Definition and Classification ............................................................................ 21 2.2 Function ............................................................................................................ 22 2.3 Structure ........................................................................................................... 25 3 The Data -

S.No District Farmer Producer Companies AHARAM

S.No District Farmer Producer Companies 1. Madurai AHARAM TRADITIONAL CROP PRODUCER COMPANY LIMITED (UO1111TN2005PTC057948) 18 Kennet Cross Road,Ellis Nagar, Madurai City 3 PIN 625 010Tamilnadu,India Tel: +91 452 2607762 Fax: +91 452 2300 369 Email: [email protected] PUDUR KALANJIAM HAND MADE PAPER PRODUCER COMPANY LIMITED (U21093TN2004PTC054106) 26, RAJIV GANDHI I STREET, LOORTHU NAGAR, II STREET, K PUDUR,MADURAI Tamil Nadu 625007 VASIMALAIAN AGRI FARMERS PRODUCER COMPANY LIMITED (U01403TN2011PTC083285) 5-248, VASI NAGAR, THOTAPPANAYAKKANOOR, USILAMPATTI, Madurai Tamil Nadu 625532 2 VILLUPURAM BHARAT MULTI PRODUCTS PRODUCER COMPANY LIMITED (U01403TN2011PTC082894) 3/1, K K Road, (Kalvi Ulagam) Villupuram 1 TN 605 602 3 SIVAGANGAI CHETTINAD PRODUCER COMPANY LIMITED (U93000TN2010PTC074592) 112. P.R.N.P street, Pallathur - 630107 Karaikudi, Sivagangai Dist 2 +91 - 4565-283050 Email: [email protected] SINGAMPUNARI COIR REGENERATION KALANJIAM PRODUCER COMPANY LIMITED (U74999TN2008PTC070213) 10-6-32/1 G H ROAD, BHARATHI NAGAR, SINGAMPUNARI, Sivagangai Dist Tamil Nadu 630502 4 THANJAVUR EAST COAST PRODUCER COMPANY LIMITED (U01400TN2011PTC081289) No. 9/15, K.P.M Colony, Subbiah Pillai Street,Pattukottai, Thanjavur, 1 Tamilnadu-614 601 5 ERODE ERODE PRECISION FARM PRODUCER COMPANY LIMITED (U51909TZ2008PTC014802) No. 42, Hospital Road, Sivagiri, Erode District, Erode - 638 109, Tamil Nadu, India +(91)-(4204)-240668 +(91)-9843165959 4 Ulavan Producer Company Limited (U01119TZ2012PTC018496) 204, BHAVANI MAIN ROAD, ERODE-Tamil Nadu 63800 Turmeric -

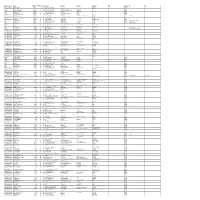

The West Bengal Backward Classes (Other Than Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes) (Reservation of Vacancies in Services and Posts) Act, 2012

Registered No. WB/SC-247 No. WB(Part-DI)/2013/SAR-7 Rottutta (IWO %%J AI "IQ Extraordinary Published by Authority CAITRA 4] MONDAY, MARCH 25, 2013 [SAKA 1935 PART EI—Acts of the West Bengal Legislature. GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL LAW DEPARTMENT Legislative NOTIFICATION No. 533-L.-25th March, 2013.—The following Act of the West Bengal Legislature, having been assented to by the Governor, is hereby published for general information:— West Bengal Act XXXIX of 2012 THE WEST BENGAL BACKWARD CLASSES (OTHER THAN SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES) (RESERVATION OF VACANCIES IN SERVICES AND POSTS) ACT, 2012. [Passed by \ tiieWest Bengal Legislature.] [Assent of the Governor was first published in the Kolkata Gazette, Extraordinary, of the 25th March, 2013.] An Act to provide for the reservation of vacancies in services and posts for the Backward Classes of citizens other than the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. WHEREAS clause (4) of article 15 of the Constitution enables the State to make any special provisions for the advancement of any socially and educationally Backward Classes of citizens; AND WHEREAS clause (4) of article 16 of the Constitution enables the State to make any provision for the reservation of appointments or posts in favour of any Backward Classes of citizens which in the opinion of the State is not adequately represented in the services under the State; 2 THE KOLKATA GAZE1TE., EXTRAORDINARY, MARCH 25, 2013 WART III • The West Bengal Backward Classes (Other than Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes) (Reservation of -

Public Works Department Irrigation Policy Note for the Year 2008-2009

Public Works Department Irrigation Policy Note for the year 2008-2009 Contents PREAMBLE 1. Water Resources Department (WRD) 2. Irrigated Agriculture Modernisation And Water Bodies Restoration 3. Dam Rehabilitation And Improvement Project (DRIP) 4. Hydrology Project-Ii 5. Cauvery-Modernisation Project 6. Irrigation Schemes 7. Flood Mitigation Schemes 8. Anti Sea Erosion Works 9. Emergency Tsunami Reconstruction Project (ETRP) 10. Chennai City Waterways 11. Artificial Recharge Of Groundwater Through Check Dams 12. Krishna Water Supply Project (KWSP) 13. Tamil Nadu Protection Of Tanks And Eviction Of Encroachment Act, 2007 14. Linking Of Rivers Within The State 15. Inter State Subjects 16. Ground Water - State Ground And Surface Water Resources Data Centre (SG&SWRDC) 17. Institute For Water Studies (IWS) 18. Irrigation Management Training Institute (IMTI) 19. Directorate Of Boilers 20. Sand Quarry PREAMBLE The Public Works Department has turned 150 years. The Department which was established in the year 1858 with just - • 1 Chief Engineer • 20 District Engineers • 3 Inspecting Engineers • 78 Executive and Assistant Engineers • 204 Upper Subordinates and • 714 Lower Subordinates has grown manifold and now functions with a strong network of • 1 Engineer-in-Chief, • 10 Chief Engineers, • 59 Superintending Engineers, • 212 Executive Engineers, • 816 Assistant Executive Engineers, • 2366 Assistant / Junior Engineers, • 1305 Technical Personnel and • 14670 Administrative Officers and staff Members • totaling 19439 employees The Public Works Department is not only 150 years, but has also earned reputation for its excellent service to the people and the State. The then Chennai Presidency had its territorial control spread over today’s Tamil Nadu, parts of Andhra Pradesh, and the Kerala State excluding the then Travancore and Kochi Princely parts. -

Antrocom Journal of Anthropology

Antrocom Online Journal of Anthropology vol. 12. n. 1 (2016) 125 - 127 – ISSN 1973 – 2880 Antrocom Journal of Anthropology journal homepage: http://www.antrocom.net Sacred Complexes as Centers of National Integration: A Case Study of the Kaveri Basin Area of Karnatka Dr. Mahadeva Siddaiah Research Assistant, Department of Studies in Anthropology, University of Mysore, Mysuru, Karnataka. India; e-mail: [email protected] KEYWORDS ABSTRACT Kaveri River, Sacred river Though there were a few anthropological studies on sacred complexes in India after the complex, pilgrimage, pioneering study of Gaya by L. P. Vidyarthi there was no such study on any sacred river complex. sociocultural integration, The studies so for conducted focused only on the interactions between pilgrims and religious South India. specialists. The present study was conducted covering nine pilgrimage centers on the sacred river complex of the Kaveri river spread over at last three linguistic areas. This study focuses on the linguistic and cultural backgrounds of the pilgrims and the local people and the sectarian diversities of the specialists. This study shows that these pilgrimage centres on the sacred river complexes act as centres of integration for the diverse linguistic, cultural and religious groups of the Hindus. Introduction Places of pilgrimage in Hindu tradition have been the subject of study by social scientists for a long time. Anthropologists, geographers and indologists have studied pilgrim centers from different theoretical perspectives (Bhardwaj, 1973; Mosinis, 1984; Bharati, 1963). Some anthropologists have analyzed the functional significance of pilgrimage and described it as a source of ‘great traditional’ knowledge and a force of socio-cultural integration (Opler, 1956, Cohn and Merriott, 1958; Vidyarthi, 1961; Srinivas, 1967; Karve 1962; Jaer, 1994). -

Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix

Marry for What? Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix By Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak and Jeanne Lafortune A. Theoretical Appendix A1. Adding unobserved characteristics This section proves that if exploration is not too costly, what individuals choose to be the set of options they explore reflects their true ordering over observables, even in the presence of an unobservable characteristic they may also care about. Formally, we assume that in addition to the two characteristics already in our model, x and y; there is another (payoff-relevant) characteristic z (such as demand for dowry) not observed by the respondent that may be correlated with x. Is it a problem for our empirical analysis that the decision-maker can make inferences about z from their observation of x? The short answer, which this section briefly explains, is no, as long as the cost of exploration (upon which z is revealed) is low enough. Suppose z 2 fH; Lg with H > L (say, the man is attractive or not). Let us modify the payoff of a woman of caste j and type y who is matched with a man of caste i and type (x; z) to uW (i; j; x; y) = A(j; i)f(x; y)z. Let the conditional probability of z upon observing x, is denoted by p(zjx): Given z is binary, p(Hjx)+ p(Ljx) = 1: In that case, the expected payoff of this woman is: A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Hjx)H + A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Ljx)L: Suppose the choice is between two men of caste i whose characteristics are x0 and x00 with x00 > x0. -

Probable Agricultural Biodiversity Heritage Sites in India

Full-length paper Asian Agri-History Vol. 17, No. 4, 2013 (353–376) 353 Probable Agricultural Biodiversity Heritage Sites in India. XVIII. The Cauvery Region Anurudh K Singh H.No. 2924, Sector-23, Gurgaon 122017, Haryana, India (email: [email protected]) Abstract The region drained by the Cauvery (Kaveri) river, particularly the delta area, falling in the state of Tamil Nadu, is an agriculturally important region where agriculture has been practiced from ancient times involving the majority of the local tribes and communities. The delta area of the river has been described as one of the most fertile regions of the country, often referred as the ‘Garden of South India’. Similarly, the river Cauvery is called the ‘Ganges of the South’. The region is a unique example of the knowledge and skills practiced by the local communities in river and water management with the construction of a series of dams for fl ood control, and the establishment of a network of irrigation systems to facilitate round- the-year highly productive cultivation of rice and other crops. Also, the region has developed internationally recognized sustainable systems with a conservational approach towards livestock rearing in semi-arid areas and fi shing in the coastal areas of the region. In the process of these developments, the local tribes and communities have evolved and conserved a wide range of genetic diversity in drought-tolerant crops like minor millets and water-loving crops like rice that has been used internationally. In recognition of these contributions, the region is being proposed as another National Agricultural Biodiversity Heritage Site based on indices used for the identifi cation of such sites. -

DOCUMENTO De TRABAJO DOCUMENTO DE TRABAJO

InstitutoINSTITUTO de Economía DE ECONOMÍA TRABAJO de DOCUMENTO DOCUMENTO DE TRABAJO 423 2012 Marry for What? Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak, Jeanne Lafortune. www.economia.puc.cl • ISSN (edición impresa) 0716-7334 • ISSN (edición electrónica) 0717-7593 Versión impresa ISSN: 0716-7334 Versión electrónica ISSN: 0717-7593 PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATOLICA DE CHILE INSTITUTO DE ECONOMIA Oficina de Publicaciones Casilla 76, Correo 17, Santiago www.economia.puc.cl MARRY FOR WHAT? CASTE AND MATE SELECTION IN MODERN INDIA Abhijit Banerjee Esther Duflo Maitreesh Ghatak Jeanne Lafortune* Documento de Trabajo Nº 423 Santiago, Marzo 2012 * [email protected] INDEX ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION 1 2. MODEL 5 2.1 Set-up 5 2.2 An important caveat: preferences estimation with unobserved attributes 8 2.3 Stable matching patterns 8 3. SETTING AND DATA 13 3.1 Setting: the search process 13 3.2 Sample and data collection 13 3.3 Variable construction 14 3.4 Summary statistics 15 4. ESTIMATING PREFERENCES 17 4.1 Basic empirical strategy 17 4.2 Results 18 4.3 Heterogeneity in preferences 20 4.4 Do these coefficients really reflect preferences? 21 4.4.1 Strategic behavior 21 4.4.2 What does caste signal? 22 4.5 Do these preferences reflect dowry? 24 5. PREDICTING OBSERVED MATCHING PATTERNS 24 5.1 Empirical strategy 25 5.2 Results 27 5.2.1 Who stays single? 27 5.2.2 Who marries whom? 28 6. THE ROLE OF CASTE PREFERENCES IN EQUILIBRIUM 30 6.1 Model Predictions 30 6.2 Simulations 30 7. -

We Refer to Reserve Bank of India's Circular Dated June 6, 2012

We refer to Reserve Bank of India’s circular dated June 6, 2012 reference RBI/2011-12/591 DBOD.No.Leg.BC.108/09.07.005/2011-12. As per these guidelines banks are required to display the list of unclaimed deposits/inoperative accounts which are inactive / inoperative for ten years or more on their respective websites. This is with a view of enabling the public to search the list of accounts by name of: Cardholder Name Address Ahmed Siddiq NO 47 2ND CROSS,DA COSTA LAYOUT,COOKE TOWN,BANGALORE,560084 Vijay Ramchandran CITIBANK NA,1ST FLOOR,PLOT C-61, BANDRA KURLA,COMPLEX,MUMBAI IND,400050 Dilip Singh GRASIM INDUSTRIES LTD,VIKRAM ISPAT,SALAV,PO REVDANDA,RAIGAD IND,402202 Rashmi Kathpalia Bechtel India Pvt Ltd,244 245,Knowledge Park,Udyog Vihar Phase IV,Gurgaon IND,122015 Rajeev Bhandari Bechtel India Pvt Ltd,244 245,Knowledge Park,Udyog Vihar Phase IV,Gurgaon IND,122015 Aditya Tandon LUCENT TECH HINDUSTAN LTD,G-47, KIRTI NAGAR,NEW DELHI IND,110015 Rajan D Gupta PRICE WATERHOUSE & CO,3RD FLOOR GANDHARVA,MAHAVIDYALAYA 212,DEEN DAYAL UPADHYAY MARG,NEW DELHI IND,110002 Dheeraj Mohan Modawel Bechtel India Pvt Ltd,244 245,Knowledge Park,Udyog Vihar Phase IV,Gurgaon IND,122015 C R Narayan CITIBANK N A,CITIGROUP CENTER 4 TH FL,DEALING ROOM BANDRA KURLA,COMPLEX BANDRA EAST,MUMBAI IND,400051 Bhavin Mody 601 / 604, B - WING,PARK SIDE - 2, RAHEJA,ESTATE, KULUPWADI,BORIVALI - EAST,MUMBAI IND,400066 Amitava Ghosh NO-45-C/1-G,MOORE AVENUE,NEAR REGENT PARK P S,CALCUTTA,700040 Pratap P CITIBANK N A,NO 2 GRND FLR,CLUB HOUSE ROAD,CHENNAI IND,600002 Anand Krishnamurthy -

Mgl-Int 1-2012-Unpaid Shareholders List As on 09

DIVIDEND WARRANT DEMAT ID_FOLIO NAME MICR ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 ADDRESS 4 CITY PINCODE JH1 JH2 AMOUNT NO 1202140000080651 SHOBHIT AGARWAL 25000.00 19 29 7/150, SWAROOP NAGAR KANPUR 208002 IN30047642921350 VAGMI KUMAR 32600.00 21 31 214 PANCHRATNA COMPLEX OPP BEDLA ROAD UDAIPUR 313001 001431 JITENDRA DATTA MISRA 12000.00 22 32 BHRATI AJAY TENAMENTS 5 VASTRAL RAOD WADODHAV PO AHMEDABAD 382415 IN30163741220512 DURGA PRASAD MEKA 10183.00 34 44 H NO 4 /60 NARAYANARAO PETA NAGARAM PALVONCHA KHAMMAM 507115 001424 BALARAMAN S N 20000.00 37 47 14 ESOOF LUBBAI ST TRIPLICANE MADRAS 600005 001440 RAJI GOPALAN 20000.00 59 69 ANASWARA KUTTIPURAM THIROOR ROAD KUTTYPURAM KERALA 679571 IN30089610488366 RAKESH P UNNIKRISHNAN 12250.00 72 82 KRISHNA AYYANTHOLE P O THRISSUR THRISSUR 680003 002151 REKHA M R 12000.00 74 84 D/O N A MALATHY MAANASAM RAGAMALIKAPURAM,THRISSUR KERALA 680004 THARA P D 1204470005875147 VANAJA MUKUNDAN 11780.00 161 171 1/297A PANAKKAL VALAPAD GRAMA PANCHAYAT THRISSUR 680567 000050 HAJI M.M.ABDUL MAJEED 20000.00 231 241 MUKRIAKATH HOUSE VATANAPALLY TRICHUR DIST. KERALA 680614 IN30189511089195 SURENDRAN 17000.00 245 255 KAKKANATT HOUSE KUNDALYUR P O THRISSUR, KERALA 680616 000455 KARUNAKARAN K.K. 30000.00 280 290 KARAYIL THAKKUTTA HOUSE CHENTRAPPINNI TRICHUR DIST. KERALA 680687 MRS. PAMILA KARUNAKARAN 001233 DR RENGIT ALEX 20000.00 300 310 NALLANIRAPPEL PO KAPPADU KANJIRAPPALLY KOTTAYAM DT KERALA 686508 MINU RENGIT 001468 THOMAS JOHN 20000.00 309 319 THOPPIL PEEDIKAYIL KARTHILAPPALLY ALLEPPEY KERALA 690516 THOMAS VARGHESE 000642 JNANAPRAKASH P.S. 2000.00 326 336 POZHEKKADAVIL HOUSE P.O.KARAYAVATTAM TRICHUR DIST.