Download Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOUISE ALDER | JOSEPH MIDDLETON Serge Rachmaninoff, Ativanovka, Hisfamily’S Country Estate,C

RACHMANINOFF TCHAIKOVSKY BRITTEN GRIEG SIBELIUS MEDTNER LOUISE ALDER | JOSEPH MIDDLETON Serge Rachmaninoff, at Ivanovka, his family’s country estate, c. 1915 estate,c. country hisfamily’s atIvanovka, Serge Rachmaninoff, AKG Images, London / Album / Fine Art Images Lines Written during a Sleepless Night – The Russian Connection Serge Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943) Six Songs, Op. 38 (1916) 15:28 1 1 At night in my garden (Ночью в саду у меня). Lento 1:52 2 2 To Her (К ней). Andante – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Tempo precedente – Tempo I (Meno mosso) – Meno mosso 2:47 3 3 Daisies (Маргаритки). Lento – Poco più mosso 2:29 4 4 The Rat Catcher (Крысолов). Non allegro. Scherzando – Poco meno mosso – Tempo come prima – Più mosso – Tempo I 2:42 5 5 Dream (Сон). Lento – Meno mosso 3:23 6 6 A-oo (Ау). Andante – Tempo più vivo. Appassionato – Tempo precedente – Più vivo – Meno mosso 2:15 3 Jean Sibelius (1865 – 1957) 7 Våren flyktar hastigt, Op. 13 No. 4 (1891) 1:35 (Spring flees hastily) from Sju sånger (Seven Songs) Vivace – Vivace – Più lento – Vivace – Più lento – Vivace 8 Säv, säv, susa, Op. 36 No. 4 (1900?) 2:32 (Reed, reed, whistle) from Sex sånger (Six Songs) Andantino – Poco con moto – Poco largamente – Molto tranquillo 9 Flickan kom ifrån sin älsklings möte, Op. 37 No. 5 (1901) 2:59 (The girl came from meeting her lover) from Fem sånger (Five Songs) Moderato 10 Var det en dröm?, Op. 37 No. 4 (1902) 2:04 (Was it a dream?) from Fem sånger (Five Songs) Till Fru Ida Ekman Moderato 4 Edvard Grieg (1843 – 1907) Seks Sange, Op. -

Festival 2021

FESTIVAL 2021 leedslieder1 @LeedsLieder @leedsliederfestival #LLF21 LEEDS LIEDER has ‘ fully realised its potential and become an event of INTERNATIONAL STATURE. It attracts a large, loyal and knowledgeable audience, and not just from the locality’ Opera Now Ten Festivals and a Pandemic! In 2004 a group Our Young Artists will perform across the weekend of passionate, visionary song enthusiasts began and work with Dame Felicity Lott, James Gilchrist, programming recitals in Leeds and this venture has Anna Tilbrook, Sir Thomas Allen and Iain steadily grown to become the jam-packed season Burnside. Iain has also programmed a fascinating we now enjoy. With multiple artistic partners and music theatre piece for the opening lunchtime thousands of individuals attending our events recital. New talent is on evidence at every turn in every year, Leeds Lieder is a true cultural success this Festival. Ema Nikolovska and William Thomas story. 2020 was certainly a year of reacting nimbly return, and young instrumentalists join Mark and working in new paradigms. We turned Leeds Padmore for an evening presenting the complete Lieder into its own broadcaster and went digital. Canticles by Britten. I’m also thrilled to welcome It has been extremely rewarding to connect with Alice Coote in her Leeds Lieder début. A recital not audiences all over the world throughout the past 12 to miss. The peerless Graham Johnson appears with months, and to support artists both internationally one of his Songmakers’ Almanac programmes and known and just starting out. The support of our we welcome back Leeds Lieder favourites Roderick Friends and the generosity shown by our audiences Williams, Carolyn Sampson and James Gilchrist. -

The Wedding of Kevin Roon & Simon Yates Saturday, the Third of October

The wedding of Kevin Roon & Simon Yates Saturday, the third of October, two thousand and nine Main Lounge The Dartmouth Club at the Yale Club New York City Introductory Music Natasha Paremski & Richard Dowling, piano Alisdair Hogarth & Malcolm Martineau, piano Welcome David Beatty The Man I Love music by George Gershwin (1898–1937) arranged for piano by Earl Wild (b. 1915) Richard Dowling, piano O Tell Me the Truth About Love W. H. Auden (1907–1973) Catherine Cooper I Could Have Danced All Night from My Fair Lady music by Frederick Loewe (1901–1988) lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner (1918–1986) Elizabeth Yates, soprano Simon Yates, piano Sonnet 116 William Shakespeare (1564–1616) Lilla Grindlay Allemande from the Partita No.4 in D major, BWV 828 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Jeremy Denk, piano Prayer of St. Francis of Assisi Eileen Roon from Liebeslieder Op. 52 Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) text by Georg Friedrich Daumer (1800–1875) translations © by Emily Ezust Joyce McCoy, soprano Jennifer Johnston, mezzo-soprano Matthew Plenk, tenor Eric Downs, bass-baritone Alisdair Hogarth & Malcolm Martineau, piano number 8 Wenn so lind dein Auge mir When your eyes so gently und so lieblich schauet, and so fondly gaze on me, jede letzte Trübe flieht, every last sorrow flees welche mich umgrauet. that once had troubled me. Dieser Liebe schöne Glut, This beautiful glow of our love, lass sie nicht verstieben! do not let it die! Nimmer wird, wie ich, Never will another love you so treu dich ein Andrer lieben. as faithfully as I. number 9 Am Donaustrande On the banks of the Danube, da steht ein Haus, there stands a house, da schaut ein rosiges and looking out of it Mädchen aus. -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

Programmealtham Wilpshire Great Harwood Ramsgreave Hapton Brownhill Huncoat Rishton

A MUSICAL CELEBRATION OF 200 YEARS OF THE CANAL! Barrowford Stonyhurst Newchurch in Pendle Barrow Fence Hurst Green A RHAPSODY TOSabden THE Nelson Brockhall Higham Village LEEDS & LIVERPOOL CANAL Whalley Brierfield Billington Simonstone Padiham Langho ProgrammeAltham Wilpshire Great Harwood Ramsgreave Hapton Brownhill Huncoat Rishton Church Oswaldtwistle Guide Crawshawbooth Lumb Waterside Rossendale Haslingden Rawtenstall Newchurch Darwen Hoddlesden Waterfoot Helmshore Cowpe Edenfield SUPER SLOW WAY: A RHAPSODY TO THE LEEDS & LIVERPOOL CANAL CONTENTS 3 Foreword 12 Biographies Laurie Peake, Super Slow Way 12 Ian McMillan, Words and Narration Richard Parry, Canal & River Trust 13 Ian Stephens, Composer 14 Clark Rundell, Conductor 4 A Rhapsody to Leeds 14 Ian Brownbill, Producer 15 Amanda Roocroft, Solo Soprano & Liverpool Canal 15 Jonathan Aasgaard, Solo Cello 16 Kuljit Bhamra, Solo Tabla 16 Farmeen Akhtar, Narrator 17 Lisa Parry, Narrator 17 Super Slow Way Chamber Choir 18 Children’s Voices of Blackburn 19 Blackburn People’s Choir 19 Brighouse and Rastrick Band superslowway.org.uk Foreword 3 LAURIE PEAKE The Leeds & Liverpool Canal was the artery that fed the Industrial Revolution, forever changing the lives and landscape of the north of England. Its history spans 200 years and, like its meandering path through the countryside, there have been many twists and turns along the way. Super Slow Way: A Rhapsody to the Leeds & Liverpool Canal is a celebration of the history, people and stories of the Leeds & Liverpool Canal through music, using a series of poems specially written by celebrated Yorkshire poet Ian McMillan. The canal was ofcially opened in Blackburn in October 1816 when, for the frst time, the journey could be made from the coalfelds of Yorkshire, through the weaving mills of Lancashire to the port of Liverpool, bringing work and industry to the towns along the way, making them centres of the Industrial Revolution and the towns we see today. -

Edward Elgar: the Dream of Gerontius Wednesday, 7 March 2012 Royal Festival Hall

EDWARD ELGAR: THE DREAM OF GERONTIUS WEDNESDAY, 7 MARCH 2012 ROYAL FESTIVAL HALL PROGRAMME: £3 royal festival hall PURCELL ROOM IN THE QUEEN ELIZABETH HALL Welcome to Southbank Centre and we hope you enjoy your visit. We have a Duty Manager available at all times. If you have any queries please ask any member of staff for assistance. During the performance: • Please ensure that mobile phones, pagers, iPhones and alarms on digital watches are switched off. • Please try not to cough until the normal breaks in the music • Flash photography and audio or video recording are not permitted. • There will be a 20-minute interval between Parts One and Two Eating, drinking and shopping? Southbank Centre shops and restaurants include Riverside Terrace Café, Concrete at Hayward Gallery, YO! Sushi, Foyles, EAT, Giraffe, Strada, wagamama, Le Pain Quotidien, Las Iguanas, ping pong, Canteen, Caffè Vergnano 1882, Skylon and Feng Sushi, as well as our shops inside Royal Festival Hall, Hayward Gallery and on Festival Terrace. If you wish to contact us following your visit please contact: Head of Customer Relations Southbank Centre Belvedere Road London SE1 8XX or phone 020 7960 4250 or email [email protected] We look forward to seeing you again soon. Programme Notes by Nancy Goodchild Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie © London Concert Choir 2012 www.london-concert-choir.org.uk London Concert Choir – A company limited by guarantee, incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and with registered charity number 1057242. Wednesday 7 March 2012 Royal Festival Hall EDWARD ELGAR: THE DREAM OF GERONTIUS Mark Forkgen conductor London Concert Choir Canticum semi-chorus Southbank Sinfonia Adrian Thompson tenor Jennifer Johnston mezzo soprano Brindley Sherratt bass London Concert Choir is grateful to Mark and Liza Loveday for their generous sponsorship of tonight’s soloists. -

University Microfilms, a XERQ\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

72- 19,021 NAPRAVNIK, Charles Joseph, 1936- CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OF ROBERT BROWNING. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D. , 1972 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, A XERQ\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan (^Copyrighted by Charles Joseph Napravnlk 1972 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE UNIVERSITY OF OKIAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OP ROBERT BROWNING A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY CHARLES JOSEPH NAPRAVNIK Norman, Oklahoma 1972 CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OF ROBERT BROWNING PROVED DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. Filmed as received. University Microfilms, A Xerox Education Company TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION...... 1 II. BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE.................. 10 III, THE RING, THE CIRCLE, AND IMAGES OF UNITY..................................... 23 IV. IMAGES OF FLOWERS, INSECTS, AND ROSES..................................... 53 V. THE GARDEN IMAGE......................... ?8 VI. THE LANDSCAPE OF LOVE....... .. ...... 105 FOOTNOTES........................................ 126 BIBLIOGRAPHY.............. ...................... 137 iii CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OP ROBERT BROWNING CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Since the founding of The Browning Society in London in 1881, eight years before the poet*a death, the poetry of Robert -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 117, 1997

i 1 997-98 SEASON Symphony Orchestra SEIJf OZAWA, Music Director r f SMfc . The Fund Market,Inc Over 2.500 Funds From 2'X> Fund Families 6l7.555.937I Fax: 1. 6:7. 555. 4679 Voice Mad: 1617.5s5.i5 Mortgage &17. 5.55.3719 126 Revere Way, Boston, MA 021 19 A Member of AGF Banx Corp. BostonPlus 1' a u 1 S i 1 v e r m a n 1-800-BBX-PLUS Direct: 413.555.1346 Voice Mail: 413.555.4769 Ife BankBoston SM BostonPlus will dramatically simplify your finances, because this one account provides all the services you need. Call BostonPlus Specialist at 1-800-BBX-PLUS. t's Amazing What You Can Do Securities and Mutual Funds: Mutual funds and securities are offered through BankBoston • Not FDIC Insured «No Bank Investor Services, Inc. (member NASD/SIPC), a wholly Guarantee • May Lose Value owned subsidiary of BankBoston, N.A. Member FDIC ~M Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Seventeenth Season, 1997-98 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. R. Willis Leith, Jr., Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Peter A. Brooke, Vice- Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Mrs. Edith L. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Nader F. Darehshori Julian T. Houston Robert P. O'Block, Gabriella Beranek Deborah B. Davis Edna S. Kalman ex-officio James F. Cleary Nina L. Doggett George Krupp Vincent M. O'Reilly John F. Cogan, Jr. Charles K. Gifford, Mrs. -

1Q12 IPG Cable Nets.Xlsm

Independent Programming means a telecast on a Comcast or Total Hours of Independent Programming NBCUniversal network that was produced by an entity Aired During the First Quarter 2012 unaffiliated with Comcast and/or NBCUniversal. Each independent program or series listed has been classified as new or continuing. 2061:30:00 Continuing Independent Series and Programming means series (HH:MM:SS) and programming that began prior to January 18, 2011 but ends on or after January 18, 2011. New Independent Series and Programming means series and programming renewed or picked up on or after January 18, 2011 or that were not on the network prior to January 18, INDEPENDENT PROGRAMMING Independent Programming Report Chiller First Quarter 2012 Network Program Name Episode Name Initial (I) or New (N) or Primary (P) or Program Description Air Date Start Time* End Time* Length Repeat (R)? Continuing (C)? Multicast (M)? (MM/DD/YYYY) (HH:MM:SS) (HH:MM:SS) (HH:MM:SS) CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 01:00:00 02:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: HORROR’S CREEPIEST KIDS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 02:30:00 04:00:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 08:00:00 09:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: HORROR’S CREEPIEST KIDS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 09:30:00 11:00:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 11:00:00 12:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER -

John Gilhooly

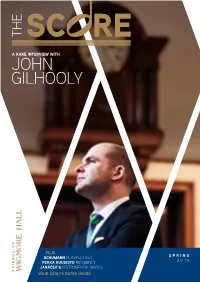

A RARE INTERVIEW WITH JOHN GILHOOLY PLUS SPRING SCHUMANN PERSPECTIVES 2018 PEKKA KUUSISTO RESIDENCY JAN ÁČEK’S INSTRUMENTAL WORKS FRIENDS OF OF FRIENDS YOUR 2018/19 DATES INSIDE John Gilhooly’s vision for Wigmore Hall extends far into the next decade and beyond. He outlines further dynamic plans to develop artistic quality, financial stability and audience diversity. JOHN GILHOOLY IN CONVERSATION WITH CLASSICAL MUSIC JOURNALIST, ANDY STEWART. FUTURE COMMITMENT “I’M IN FOR THE LONG HAUL!” Wigmore Hall’s Chief Executive and Artistic Director delivers the makings of a modern manifesto in eight words. “This is no longer a hall for hire,” says John Gilhooly, “or at least, very rarely”. The headline leads to a summary of the new season, its themed concerts, special projects, artist residencies and Learning events, programmed in partnership with an array of world-class artists and promoted by Wigmore Hall. It also prefaces a statement of intent by a well-liked, creative leader committed to remain in post throughout the next decade, determined to realise a long list of plans and priorities. “I am excited about the future,” says John, “and I am very grateful for the ongoing help and support of the loyal audience who have done so much already, especially in the past 15 years.” 2 WWW.WIGMORE-HALL.ORG.UK | FRIENDS OFFICE 020 7258 8230 ‘ The Hall is a magical place. I love it. I love the artists, © Kaupo Kikkas © Kaupo the music, the staff and the A glance at next audience. There are so many John’s plans for season’s highlights the Hall pave the confirms the strength characters who add to the way for another 15 and quality of an colour and complexion of the years of success. -

Buffy at Play: Tricksters, Deconstruction, and Chaos

BUFFY AT PLAY: TRICKSTERS, DECONSTRUCTION, AND CHAOS AT WORK IN THE WHEDONVERSE by Brita Marie Graham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSTIY Bozeman, Montana April 2007 © COPYRIGHT by Brita Marie Graham 2007 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by Brita Marie Graham This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Linda Karell, Committee Chair Approved for the Department of English Dr. Linda Karell, Department Head Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox, Vice Provost iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it availably to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Brita Marie Graham April 2007 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In gratitude, I wish to acknowledge all of the exceptional faculty members of Montana State University’s English Department, who encouraged me along the way and promoted my desire to pursue a graduate degree.