Srammohun Roy, His Intellectual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander Duff Pioneer of Missionary Education Alexand Er Duff a T Th I Rty Alexander Duff Pioneer of Missionary Education

ALEXANDER DUFF PIONEER OF MISSIONARY EDUCATION ALEXAND ER DUFF A T TH I RTY ALEXANDER DUFF PIONEER OF MISSIONARY EDUCATION By WILLIAM PATON ACTING SECRETARY OF THB INDIA NATIONAL MISSIONARY COUNCIL LATE MISSIONARY SECRETARY OF THE STUDENT CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT JOINT• AUTHOR OF "THE HIGHWAY OF GOD" AND AUTHOR OF "SOCIAL IDEALS IN INDIA, 11 ETC. WNDON STUDENT CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT 32 RUSSELL SQUARE, W.C.l 1923 Made atul Printed in Great Britain by Turnbwll 6' Spears, Edinburrlt EDITORIAL NOTE THIS volume is the second of a uniform series of new missionary biographies. The series makes no pretence of adding new facts to those already known. The aim rather is to give to the world of to-day a fresh interpretation and a richer understanding of the life and work of great missionaries. A group of unusually able writers are collaborating, and three volumes will be issued each year. The enterprise is being undertaken by the United Council for Missionary Education, for whom the series is published by the Student Christian Move ment. K. M. U.C.M.E. A. E. C. 2 EATON GATE S.W.l 6 TO DAVID AND JAMES AUTHOR'S PREFACE SoME apology is needed for the appearance of a new sketch of the life of Alexander Duff, especially as the present writer cannot lay claim to any special sources of information which were not available when the earlier biographies were written. The reader will not find in this book fresh light on Duff, except in so far as the course of events in itself proves a man's work and makes clear its strength and weakness. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Hindi, an Indo-European language, is the official language of India, spoken by about 40% of the more than one billion citizens of India. It is also the official language in certain of the territories where a sizeable diaspora settled such as the Republic of Mauritius1. But the label ‘Hindi’ covers considerably distinct speeches, as evidenced by the number of regional varieties covered by the category Hindi in the various Censuses of India: 91 mother tongues in the 1961 Census, up to 331 languages or speeches according to Srivastava 1994, totalizing to six hundred millions speakers (Bhatia 1987: 9). On the other end, the notion that Standard Hindi, more or less corresponding to the variety used in written literature and media, does not exist as a mother tongue, has gained currency during the seventies and eighties: according to Gumperz & Naim (1960), modern standard Hindi is a second or third speech for most of its speakers, being a native language for a small section of the urban population, which until recently was itself a small minority of the global Indian population. However, due to the rapid increase in this urban population, Hindi native speakers can no longer be considered as a non-significant minority, as noticed by Ohala (1983) and Singh & Agnihotri (1997). Many scholars still consider that the modern colloquial language, used for instance in popular movies, does not differ from modern colloquial Urdu. Similarly, many consider that the higher registers of both languages are still only two styles of one and the same language. According to Abdul Haq (1961), “the language we speak and write and call by the name Urdu today is derived from Hindi and constituted of Hindi”. -

How the Vision of the Serampore Quartet Has Come Full Circle

Oxford Centre for Christianity and Culture, Centre for Baptist History and Heritage and Baptist Historical Society The heritage of Serampore College and the future of mission From the Enlightenment to modern missions: how the vision of the Serampore Quartet has come full circle John R Hudson 20 October 2018 The vision of the Serampore Quartet was an eighteenth century Enlightenment vision involving openness to ideas and respect for others and based on the idea that, for full understanding, you need to study both the ‘book of nature’ and the ‘book of God.’ Serampore College was a key component in the working out of this wider vision. This vision was superseded in Britain by the racist view that European civilisa- tion is superior and that Christianity is the means to bring civilisation to native peoples. This view had appalling consequences for native peoples across the Empire and, though some Christians challenged it, only in the second half of the twentieth century did Christians begin to embrace a vision more respectful of non-European cultures and to return to a view of the relationship between missionaries and native peoples more akin to that adopted by the Serampore Quartet. 1 Introduction Serampore College was not set up in 1818 as a theological college though ministerial training was to be part of its work (Carey et al., 1819); nor was it a major part, though it remains the most visible legacy of, the work of the Serampore Quartet.1 Rather it came as an outgrowth of the wider vision of the Serampore Quartet — a wider vision which, I will argue, arose from the eighteenth century Enlightenment and which has been rediscovered as the basis for mission in the second half of the twentieth century. -

Wilson Brought out a New Edition of Mill's History of British India, in Which He Footnoted What He Thought to Be Mill's Errors

HORACE HAYMAN WILSON AND GAMESMANSHIP IN INDOLOGY NATALIE P. R. SIRKIN SHORTLY AFTER THE DEATH OF JAMES MILL) HORACE HAYMAN Wilson brought out a new edition of Mill's History of British India, In which he footnoted what he thought to be Mill's errors. Review ing these events in a recent survey of nineteenth-century Indian historians, Professor C. H. Philips comments: It is incredible that he should not have chosen to write a new history altogether, but possibly his training as a Sanskritist, which had accustomed him to the method of interpreting a text in this way, had something to do with his choice.' But why? Professor Philips might as well have asked why he did not write his own books on Hindoo law and on Muslim law instead of bringing out a new edition of Macnaghten; or why he did not collect his own proverbs, instead of editing the Hindoostanee and Persian proverbs of Captain Roebuck and Dr. Hunter; or why he did not write his own book on travels in the Himalayas, instead of editing Moorcroft's; or why he did not write his own book on Sankhya philosophy, instead of editing H. T. Colebrooke's : or why he hid not write his own book 011 archaeology in Afghanistan, instead of using Masson's materials.. To suggest Mr. Wilson might have written his OWll History of British India is to suggest that' he was a scholar and that he was interested in the subject. As to the latter, he never wrote again on the subject. As to the former, his education had not prepared him for it, Educated (as the Dictionary of National Biography reports) "in Soho Square," he then .apprenticed himself in a London .hos pital and proceeded to Calcutta as a surgeon for the East India Company. -

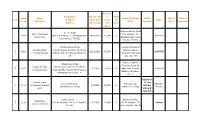

Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application (Receving) Basic Pay / Pay in Pay Band Type

Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. Name Name & Address Roster Date of Date of Sl. No. & Office Application Pay in of Status Sl. No S/D/W/O D.D.O. Category Birth Retirement Address (Receving) Pay Flat Band Accounts Officer, 9D & Gr. - II Sister Smt. Anita Biswas B.G. Hospital , 57, 1 1879 9D & B.G. Hospital , 57, Beleghata Main 28/12/2012 21,140 A ALLOTTED Sri Salil Dey Beleghata Main Road, Road, Kolkata - 700 010 Kolkata - 700 010 District Fishery Officer Assistant Director of Bikash Mandal O/O the Deputy Director of Fisheries, Fisheries, Kolkata 2 1891 31/12/2012 22,500 A ALLOTTED Lt. Joydev Mandal Kolkata Zone, 9A, Esplanade East, Kol - Zone, 9A, Esplanade 69 East , Kol - 69 Asstt. Director of Fishery Extn. Officer Fisheries, South 24 Swapan Kr. Saha O/O The Asstt. Director of Fisheries 3 1907 1/1/2013 17,020 A Pgns. New Treasury ALLOTTED Lt. Basanta Saha South 24 Pgs., Alipore, New Treasury Building (6th Floor), Building (6th Floor), Kol - 27 Kol - 27 Eligible for Samapti Garai 'A' Type Assistant Professor Principal, Lady Allotted '' 4 1915 Sri Narayan Chandra 2/1/2013 20,970 A flats but Lady Brabourne College Brabourne College B'' Type Garai willing 'B' Type Flat Staff Nurse Gr. - II Accounts Officer, Lipika Saha 5 1930 S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, A.J.C. Bose Rd. , 4/1/2013 16,380 A S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, Allotted Sanjit Kumar Saha Kol -20 A.J.C. Bose Rd. , Kol -20 Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. -

Contribution of British East India Company on Medical College

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 8 Issue 11 Ser. I || November 2019 || PP 75-76 Contribution of british east india company on Medical college Mr. Sk Ahammad Raja Post graduation pass in History from Netaji Subhas Open University in 2018. ABSTRACT – The east India company played a very important in history of India. Many historians and many books as tells us something about their persecution same time we come to know some good work also of them. Therefore, let us discuss some good views of them. They brought modern technology of medication. Keywords – Background of establishing a medical college, the Old system of medication was not so good, Establishment of Kolkata Medical College, Student Admission, Anatomy and dissection of the body. Education Methods College building ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- --------- Date of Submission: 27-10-2019 Date of acceptance: 15-11-2019 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- --------- I. INTRODUCTION - During the reign of Governor-General Lord William Bentinck in 1835. A new chapter in the history of medical science of India and medical science established at Medical College, Kolkata Started The proposal that Bentick and his council adopted was: "That a new College shall be formed for the instruction of a certain number of native youths in the various Branches of medical science ". In an earlier proposal, they rubbed off conventional Native Medical .Medical classes that took place at Institution and Sanskrit College and Madrase were canceled. Bentick Determine that the college will be under the supervision of the Education Committee. Background of establishing a medical collage In Bengal before the establishment of a medical college in 1835 There were various types of errors and weaknesses in medical education. -

Historical Notes: Indian Renaissance: the Making of Modern India

Indian Journal of History of Science, 46.1 (2011) 131-154 HISTORICAL NOTES INDIAN RENAISSANCE: THE MAKING OF MODERN INDIA Sisir K. Majumdar* (Received 16 July 2010) Introduction The history of the Indian renaissance in the 19th century and the European Renaissance in the 14th century offers us a pleasant contrast and also a curious scenario of creative synthesis of the best of the East and the West. With the adoption of English as the official language of British India in 1834, a phase of confrontation, co-operation and imitation started. But the main outcome was the resurrection of nationalist ideals and perceptions in the newly growing urban centers of India—a definite re-awakening; a new renainssance became noticeable. All other negative aspects silently slipped into oblivion and obscurity. The cultural and intellectual heritage of modern India derives largely from this phase of questioning and search. This was the beginning of the making of modern India. It generated an inner quality of earnest inquiry and search, of contemplation and action, of balance and equilibrium, in spite of conflict and contradiction. There was a poise in it and a unity in the midst of disparity and diversity, and its temper was one of supremacy over the changing environment, not by seeking escape from it, but fitting in with it, in order to move with the dynamic history of changing world. Ram Mohan: The First of the Moderns Politically, the period of ten decades between the Battle of Plassey (1757) and the Sepoy Mutiny (1857) was the era of expansion of the British Empire in India and of its subsequent consolidation. -

John Benjamins Publishing Company Historiographia Linguistica 41:2/3 (2014), 375–379

Founders of Western Indology: August Wilhelm von Schlegel and Henry Thomas Colebrooke in correspondence 1820–1837. By Rosane Rocher & Ludo Rocher. (= Abhandlungen für die Kunde des Morgenlandes, 84.) Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2013, xv + 205 pp. ISBN 978-3-447-06878-9. €48 (PB). Reviewed by Leonid Kulikov (Universiteit Gent) The present volume contains more than fifty letters written by two great scholars active in the first decades of western Indology, the German philologist and linguist August Wilhelm von Schlegel (1767–1789) and the British Indologist Henry Thomas Colebrooke (1765–1837). It can be considered, in a sense, as a sequel (or, rather, as an epistolary appendix) to the monograph dedicated to H. T. Colebrooke that was published by the editors one year before (Rocher & Rocher 2012). The value of this epistolary heritage left by the two great scholars for the his- tory of humanities is made clear by the editors, who explain in their Introduction (p. 1): The ways in which these two men, dissimilar in personal circumstances and pro- fessions, temperament and education, as well as in focus and goals, consulted with one another illuminate the conditions and challenges that presided over the founding of western Indology as a scholarly discipline and as a part of a program of education. The book opens with a short Preface that delineates the aim of this publica- tion and provides necessary information about the archival sources. An extensive Introduction (1–21) offers short biographies of the two scholars, focusing, in particular, on the rise of their interest in classical Indian studies. The authors show that, quite amazingly, in spite of their very different biographical and educational backgrounds (Colebrooke never attended school and universi- ty in Europe, learning Sanskrit from traditional Indian scholars, while Schlegel obtained classical university education), both of them shared an inexhaustible interest in classical India, which arose, for both of them, due to quite fortuitous circumstances. -

India Freedom Fighters' Organisation

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of Political Pamphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Part 5: Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT PART 5: POLITICAL PARTIES, SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS, AND INDIAN INTERNAL POLITICS Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. Content: pt. 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups—pt. 2. Indian Internal Politics—[etc.]—pt. 5. Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics ISBN 1-55655-829-5 (microfiche) 1. Political parties—India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1 I527 2000 <MicRR> 324.254—dc20 89-70560 CIP Copyright © 2000 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-829-5. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................. vii Source Note ............................................................................................................................. xi Reference Bibliography Series 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups Organization Accession # -

2021 Banerjee Ankita 145189

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Santiniketan ashram as Rabindranath Tagore’s politics Banerjee, Ankita Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 THE SANTINIKETAN ashram As Rabindranath Tagore’s PoliTics Ankita Banerjee King’s College London 2020 This thesis is submitted to King’s College London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy List of Illustrations Table 1: No of Essays written per year between 1892 and 1936. -

'A Christian Benares' Orientalism, Science and the Serampore Mission of Bengal»

‘A Christian Benares’: Orientalism, science and the Serampore Mission of Bengal Sujit Sivasundaram Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge By using the case of the Baptist missionaries called the ‘Serampore Trio’—Rev. William Carey, Rev. William Ward and Rev. Joshua Marshman—this article urges that science and Christianity were intimately related in early nineteenth-century north India. The Serampore Baptists practised a brand of Christian and constructive orientalism, devoting themselves to the recovery of Sanskrit science and the introduction of European science into India. Carey established an impressive private botanical garden and was instrumental in the formation of the Agricultural Society of India. Ward, in his important account of Hinduism, argued that true Hindu science had given way to empiricism, and that Hindus had confused nature with the divine. The Serampore College formed by the trio sought to educate Indians with respect to both Sanskrit and European science, and utilised a range of scientific instruments and texts on science published in India. The College aimed to change the way its pupils saw the material world by urging experimen- tation rather than reverence of nature. The style of science practised at Serampore operated outside the traditional framework of colonial science: it did not have London as its centre, and it sought to bring indigenous traditions into a dialogue with European science, so that the former would eventually give way to the latter. The separation of science and Christianity as discrete bodies of intellectual en- deavour is alleged to be central to the emergence of modernity. Until recently, scholars cast modern science as a Western invention, which diffused across the world on the winds of empires, taking seed and bringing nourishment to all human- ity.1 Those who studied the spread of Christianity took a similar position in urging the transplantation of European values and beliefs wholesale by evangelists.2 These views have been decisively recast in the past two decades. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies.