The Book House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZHAW SML Fact Sheet 2021-2022.Pdf

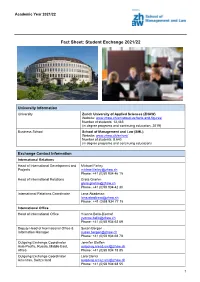

Academic Year 2021/22 Fact Sheet: Student Exchange 2021/22 University Information University Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) Website: www.zhaw.ch/en/about-us/facts-and-figures/ Number of students: 13,485 (in degree programs and continuing education, 2019) Business School School of Management and Law (SML) Website: www.zhaw.ch/en/sml/ Number of students: 8,640 (in degree programs and continuing education) Exchange Contact Information International Relations Head of International Development and Michael Farley Projects [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 46 15 Head of International Relations Greta Gnehm [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 42 30 International Relations Coordinator Lena Abadesso [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 77 15 International Office Head of International Office Yvonne Bello-Bischof [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 62 69 Deputy Head of International Office & Susan Bergen Information Manager [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 68 78 Outgoing Exchange Coordinator Jennifer Steffen Asia-Pacific, Russia, Middle East, [email protected] Africa Phone: +41 (0)58 934 78 85 Outgoing Exchange Coordinator Lara Clerici Americas, Switzerland [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 68 55 1 Academic Year 2021/22 Outgoing Exchange Coordinator Miguel Corredera Europe [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 41 02 Incoming Exchange Coordinator Alice Ragueneau Overseas [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 62 51 Incoming Exchange Coordinator Sandra Aerne Europe -

Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 Ó Copyright by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 by Joanna Marie Fiduccia Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor George Thomas Baker, Chair This dissertation presents the first extended analysis of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture between 1935 and 1945. In 1935, Giacometti renounced his abstract Surrealist objects and began producing portrait busts and miniature figures, many no larger than an almond. Although they are conventionally dismissed as symptoms of a personal crisis, these works unfold a series of significant interventions into the conventions of figurative sculpture whose consequences persisted in Giacometti’s iconic postwar work. Those interventions — disrupting the harmonious relationship of surface to interior, the stable scale relations between the work and its viewer, and the unity and integrity of the sculptural body — developed from Giacometti’s Surrealist experiments in which the production of a form paradoxically entailed its aggressive unmaking. By thus bridging Giacometti’s pre- and postwar oeuvres, this decade-long interval merges two ii distinct accounts of twentieth-century sculpture, each of which claims its own version of Giacometti: a Surrealist artist probing sculpture’s ambivalent relationship to the everyday object, and an Existentialist sculptor invested in phenomenological experience. This project theorizes Giacometti’s artistic crisis as the collision of these two models, concentrated in his modest portrait busts and tiny figures. -

Betty Parsons Heated Sky Alexander Gray Associates Gray Alexander Betty Parsons: Heated Sky February 26 – April 4, 2020

Betty Parsons Sky Heated Betty Parsons: Heated Sky Alexander Gray Associates Betty Parsons: Heated Sky February 26 – April 4, 2020 Alexander Gray Associates Betty Parsons in her Southold, Long Island, NY studio, Spring 1980 2 3 Betty Parsons in her Southold, Long Island, NY studio, 1971 5 Introduction By Rachel Vorsanger Collection and Research Manager Betty Parsons and William P. Rayner Foundation Betty Parsons’ boundless energy manifested itself not only in her various forms of artistic expression—paintings of all sizes, travel journals, and her eponymous gallery— but in her generosity of spirit. Nearly four decades after Parsons’ death, her family, friends, and former colleagues reinforce this character trait in conversations and interviews I have conducted, in order to better understand the spirit behind her vibrant and impassioned works. Betty, as I have been told was her preferred way to be addressed, was a woman of many actions despite her reticent nature. She took younger family members under her wing, introducing them to major players in New York’s mid-century art world and showing them the merits of a career in the arts. As a colleague and mentor, she encouraged the artistic practice of gallery assistants and interns. As a friend, she was a constant source of inspiration, often appearing as the subject of portraits and photographs. Perhaps her most deliberate act of generosity was the one that would extend beyond her lifetime. As part of her will, she established the Betty Parsons Foundation in order to support emerging artists from all backgrounds, and to support ocean life. After her nephew Billy Rayner’s death in 2018, the Foundation was further bolstered to advance her mission. -

Field Report Florence Meeting Bern/Winterthur

Gesundheit Field Report Florence Meeting Bern/Winterthur 18.-22. April 2017 Bern Fachhochschule in collaboration with ZHAW and FH Ostschweiz, Bern and Winterthur, Switzerland Students and Staff, Bachelor Midwifery and Nursing, various study years The conference of the 25th Florence Network Annual Meeting took place from Tuesday 18th April – Saturday 22th April 2017 in Switzerland. We spent four days in Bern at the University of Applied Sciences and one day in Winterthur, in cooperation with the Zurich University of Applied Sciences and the University of Applied Sciences St. Gallen. The conference theme was “Mental Health: Global Challenge – Local Actions”. During the week, the differences between the health care systems of the participating countries and especially those regarding mental health care were discussed. Keynote speakers talked about mental health and various workshops on different aspects of mental health were offered. The WHO defined 2017 Mental Health as “a state of well-being”. But what does that mean? Mental Health in Midwifery Due to the vulnerability of the perinatal period, a lot of women and men suffer from mental illnesses during this stage of life. That is why the midwifery workshops and keynote speeches of the FNAM were mainly about the topic of perinatal and above all postnatal depression and its treatment. According to Anke Berger’s presentation, 18% of Swiss pregnant women and 19% of new mothers suffer from a mental disorder. Although this is a high percentage, only 50% of these women are detected and can be treated. The treatment itself is a big challenge as psychopharmacological drugs may influence the foetus as well as the composition of breast milk. -

Displacement and Repetition

3 Everything in the painting contributes to a feeling of unending dis- placement and discomfort. The young woman dressed in black, upon whom DISPLACEMENT AND REPETITION our attention inevitably falls, is standing to one side in a room, a short dis- tance from the closed door, where the bulky slanted desk takes up most of John Yau the space. Her head dips slightly downward, as if she might be looking at the doorknob. Since we can see only her back, we cannot say for certain what she is doing, which is why she remains unfathomable within the array of lines and edges that grasp her. Look at how she is poised between the doorknob on the right and the doorframe’s edge on the left, everything holding her in What we seldom talk about in art is the desperation informing much of it, place without ever touching her. And yet, she will never reach the door or not because the artists are good at disguising it, but because we seem to not leave the room. An everlasting moment of impenetrable stillness envelops want to see what is in front of our eyes. Even in works that might initially the painting. She is both displaced and stuck in time, while chaos and pan- strike the viewer as beautifully ordered, one need only look a little longer to demonium wait outside the door. see how hard the artist has worked to present his or her anxiety as a moment Where will this young woman go? In Alberto Giacometti’s case, she is of sublime calm. -

Maps Heerbrugg En.Qxp:4507 Leica Map.Qxp

Leica Geosystems Heerbrugg Switzerland From Zürich Airport to Heerbrugg: Austria …by car Au From the airport in Zürich, follow the green & white Border/ highway signs to the A1 highway towards Zurich - Gallen/Zürich St. Customs Winterthur – St. Gallen. Exit Remain on the A1 highway in St. Gallen and follwing to Au the signs to the A13, towards St. Margrethen – Chur. After approximately 110 km (1h15 min drive) from the airport, leave the highway at exit Au, Lustenau. Heerbrugg To At the end of the exit, turn to the right towards Au / Berneck. Take the third exit at the roundabout towards Heerbrugg. (Austria) Lustenau Krönele, Hotel 10 There are 5 traffic lights between there and the Post DC Widnau Heinrich-Wild-Strasse Berneck To office headoffices of Leica Geosystems, still approximately 3,5 km away. At the fourth traffic light, you will have reached the Heerbrugg Bus station other end of Heerbrugg and the premises of Leica To Altstätten Geosystems will be on your left. Railway station A13 Motorway Drive on and 300 m after the sign designating the 2 8 Rhine 7 1 village of Balgach, turn left into the Heinrich-Wild- Leica To Heerbrugg 4 6 Strasse on the far end of the Leica Geosystem 3 9 5 premises. Widnau The parking lot for visitors is locatecd directly in front Car Hotel Forum Wash Hotel Löwen of the reception building of Leica Geosystems Hotel Metropol (first building on the left) (Please remember that there is an annual permit to be paid for using the highways in Switzerland. Hotel Hotel Coop Hotel To WidnauFreihof All cars using the highways must have the paid Bad Balgach Supermarket Heerbrugghof permit or “vignette” glued on their windshields) Roundabout Traffic light Canal …by train Exit to To Allow at least 30 minutes between arrival of the Bus stop Widnau/ Diepoldsau Diepoldsau plane and the departure of the train. -

09:30 Joint SSP-EFP Session COVID-19 08:30

Scientific Programme Thursday, 17 June 2021 Joint Sessions, Virtual Room 1 08:30 - 09:30 Joint SSP-EFP Session COVID-19 Chair: Michael Tamm (Basel, Switzerland) Chair: Zouhair Souissi (Tunis, Tunisia) 08:30 - 08:40 Short 2021 update on treatment options in COVID19 Alexandra Calmy (Geneva, Switzerland) 08:40 - 08:50 COVID in children: (including multisystem inflammatory syndrome) Arnaud L’Huillier (Geneva, Switzerland) 08:50 - 09:00 Acute respiratory failure in COVID patients outside the ICU Dan Adler (Geneva, Switzerland) 09:00 - 09:10 COVID and vascular disease (vasculitis, thromboembolic disorders..) Marc Righini (Geneva, Switzerland) 09:10 - 09:20 Swiss COVID lung study Manuela Funke-Chambour (Bern, Switzerland) 09:20 - 09:30 Q & A Joint Sessions, Virtual Room 2 08:30 - 09:30 Joint SSP-EFP Session Sleep disordered breathing 1 Chair: Robert Thurnheer (Münsterlingen, Switzerland) Chair: Quy Ngo Chau (Hanoi, Viet Nam) 08:30 - 08:50 New Swiss recommendations 2020 for the diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnoea Raphaël Heinzer (Lausanne, Switzerland) 08:50 - 09:05 Residual sleepiness in patients treated for sleep apnoea Jean-Louis Pepin (Grenoble, France) 09:05 - 09:20 New treatments for OSA Malcolm Kohler (Zürich, Switzerland) 09:20 - 09:30 Q & A Joint Sessions, Virtual Room 3 08:30 - 09:30 Joint SSP-EFP Session E-cigarettes Chair: Macé Schuurmans (Winterthur, Switzerland) Chair: Florin Mihaltan (Bucharest, Romania) Page 1 / 18 Scientific Programme 08:30 - 08:45 Toxicity of E-Cigarettes Philippe Camus (Dijon, France) 08:45 - 09:00 E-cigarettes and „Heat not burn devices“: an individual opportunity, but risks for society Jacques Cornuz (Lausanne, Switzerland) 09:00 - 09:15 Impact of e-cigarettes on smoking in adolescents Jürg Barben (St. -

Zurich University of Applied Sciences School of Management and Law Winterthur

Zurich University of Applied Sciences School of Management and Law Winterthur Bachelor’s Thesis Introduction of Capacity Mechanisms in European Energy Markets: Implications for Swiss Market Participants Supervisor Johanna Cludius Author Casper Erik Wilbers Einfangstrasse 19 8406 Winterthur [email protected] S12467338 Winterthur, 22. Mai 2015 Casper Erik Wilbers Declaration of authorship I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work, that it has been generated by me without the help of others and that all sources are clearly referenced. I further declare that I will not supply any copies of this thesis to any third parties without written permission by the director of this degree program. I understand that the Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) reserves the right to use plagiarism detection software to make sure that the content of this thesis is completely original. I hereby agree for this thesis, naming me as its author, to be sent abroad for this purpose, where it will be kept in a database to which this university has sole access. I also understand that I will be entitled at any time to ask for my name and any other personal data to be deleted. Furthermore, I understand that pursuant to § 16 (1) in connection with § 22 (2) of the federal law on universities of applied sciences (FaHG) all rights to this thesis are assigned to the ZHAW, except for the right to be identified as its author. Student’s name (in block letters) Casper Erik Wilbers Student’s signature ………………………………………….. Bachelor’s Thesis - Introduction of Capacity Mechanisms in European Energy Markets i Casper Erik Wilbers Lecturer’s statement concerning publication This statement concerns the publication1) of the bachelor thesis “Introduction of Capacity Mechanisms in European Energy Markets: Implications for Swiss Market Participants”. -

Participation of Children and Parents in the Swiss Child Protection System in the Past and Present: an Interdisciplinary Perspective

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Participation of Children and Parents in the Swiss Child Protection System in the Past and Present: An Interdisciplinary Perspective Aline Schoch 1,*, Gaëlle Aeby 2,* , Brigitte Müller 1, Michelle Cottier 2, Loretta Seglias 3, Kay Biesel 1, Gaëlle Sauthier 4 and Stefan Schnurr 1 1 Institute for Studies in Children and Youth Services, School of Social Work, University of Applied Sciences Northwestern Switzerland FHNW, 4132 Muttenz, Switzerland; [email protected] (B.M.); [email protected] (K.B.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 Centre for Evaluation and Legislative Studies, Faculty of Law, University of Geneva, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland; [email protected] 3 Independent researcher, 8820 Wädenswil, Switzerland; [email protected] 4 Centre for Children’s Rights Studies, University of Geneva, 1950 Sion, Switzerland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (G.A.) Received: 6 July 2020; Accepted: 12 August 2020; Published: 18 August 2020 Abstract: As in other European countries, the Swiss child protection system has gone through substantial changes in the course of the 20th century up to today. Increasingly, the needs as well as the participation of children and parents affected by child protection interventions have become a central concern. In Switzerland, critical debates around care-related detention of children and adults until 1981 have led to the launch of the National Research Program ‘Welfare and Coercion—Past, Present and Future’ (NRP 76), with the aim of understanding past and current welfare practices. This paper is based on our research project, which is part of this national program. -

Information Sheet Student Exchange Programs

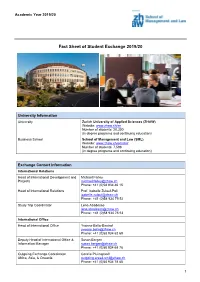

Academic Year 2019/20 Fact Sheet of Student Exchange 2019/20 University Information University Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) Website: www.zhaw.ch/en Number of students: 20,300 (in degree programs and continuing education) Business School School of Management and Law (SML) Website: www.zhaw.ch/en/sml/ Number of students: 7,598 (in degree programs and continuing education) Exchange Contact Information International Relations Head of International Development and Michael Farley Projects [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 46 15 Head of International Relations Prof. Isabelle Zulauf-Poli [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 79 52 Study Trip Coordinator Lena Abadesso [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 75 53 International Office Head of International Office Yvonne Bello-Bischof [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 62 69 Deputy Head of International Office & Susan Bergen Information Manager [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 68 78 Outgoing Exchange Coordinator Coralie Pluimgraaff Africa, Asia, & Oceania [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 78 85 1 Academic Year 2019/20 Outgoing Exchange Coordinator Lara Clerici Americas, Switzerland [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 68 55 Outgoing Exchange Coordinator Miguel Corredera Europe [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 4102 Incoming Exchange Coordinator Alice Ragueneau Overseas [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 62 51 Incoming Exchange Coordinator Natalie Covos Europe [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 73 05 Address of International Office ZHAW School of Management and Law International Office St.-Georgen-Platz 2 P.O. -

AC., AC, Bon Sans Coupes +

Françoise Bridel Accrocs, accrochages Hookings, Hangings et and Codicille Codicil: Working on the Book par François Albera by François Albera Supporter l’image Maintaining the image par Maria Tortajada by Maria Tortajada Translation: Yves Abrioux 1 Collections 1986, acrylique sur papier marouflé, 12 pièces, 90 cm x 150 cm, Deposito Figure, Pesaro 2 Vue d’avion 1980, performance, acrylique sur drap, 340 cm x 600 cm, Fri-Art, Fribourg 3 Les mouchoirs de l’Alhambra 1979, performance, acrylique sur soie, 12 pièces, 25 cm x 35 cm, Genève 4 Flammèches 1980, performance, acrylique sur soie, 10 pièces, 25 cm x 35 cm, Genève 5, 6 Papillons 1980, performance, acrylique sur papier pergamine, 12 pièces, 10 cm x 10 cm, Genève François Albera François Albera Accrocs, accrochages Hooking and Hanging Baudelaire dans «Le peintre de la vie moderne» se réfère In “The Painter of Modern Life”, Baudelaire refers to the anony- à l’anonyme M. G. (Constantin Guys) –«homme des mous M.G. (Constantin Guys) –“ man of crowds ”– , not so much in foules»– moins pour poser les bases de ce qu’on appel- order to lay the foundations of what would later come to be known lera bien plus tard la «peinture moderne» et a fortiori le as “modern painting” nor indeed of modernism as such (which modernisme (qui trouvera son achèvement dans la doc- culminated in the doctrine of “artistic autonomy”), but rather to trine de l’«autonomie de l’art»), que pour définir quelques define a number of tasks incumbent upon the painting of modern, tâches incombant à la peinture de la vie moderne, c’est- i.e. -

CHÊNE-BOURG ET THÔNEX La Mobilité Au Cœur Du Développement Des Trois-Chêne Un Reportage De Frédéric Montanya

Agendafondé culturel en 1915 inclus mai 2014 – No 503 ORGANE OFFICIEL DES COMMUNES DE CHÊNE-BOUGERIES, CHÊNE-BOURG ET THÔNEX La mobilité au cœur du développement des Trois-Chêne Un reportage de Frédéric Montanya Même retardé, le CEVA est un projet aux implications majeures sur la mobilité des Trois-Chêne. Mais il ne faut pas que l’arbre, aussi gros soit-il, cache la forêt. Car les trois communes ont d’autres projets essentiels. Le réaménagement du périmètre de la gare avec la création de l’hypercentre à Chêne-Bourg, la refonte du Cœur de Village à Chêne-Bougeries ou les Com munaux d’Ambilly à Thônex: tous entraîneront une forte augmentation de la population. Gérer les besoins en mobilité qui en découlent, aujourd’hui comme dans les 15 ans à venir, c’est l’objectif que se sont fixé les communes des Trois-Chêne. Tour d’horizon. Longtemps envisagé, le déplacement de l’arrêt du tram sur la route de Chêne, au Après son agrandissement de 450 à 900 places, le P+R de Sous-Moulin, idéalement niveau de l’école primaire de Chêne-Bougeries, est désormais acquis. situé et bénéficiant d’une bonne desserte en transports publics, ne désemplit pas. CEVA - O. Zimmermann CEVA © Les habitants de Chêne-Bourg devront attendre jusqu’en 2017 pour jouir d’une Chantier CEVA: la réalisation de la future tranchée couverte de Frank-Thomas, en place de la Gare réaménagée de manière définitive. parois moulées, côté Chêne-Bougeries. Délai rédactionnel et publicitaire: Sommaire 19 mai 2014 Avis 2 Informations officielles 23 Musique 43 Trois-Chêne 23 Loisirs 44 Dossiers: