Found in Translation: Interdisciplinary Arts Integration in Project AIM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

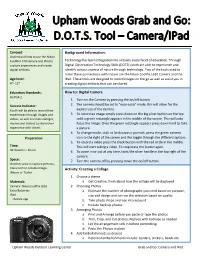

Grab and Go Camera and Ipad

Concept: Background Information: Understand how to use the Nikon CoolPix L610 camera and IPad to Technology has been integrated into virtually every facet of education. Through capture experiences and create Digital Observation Technology Skills (DOTS) youth are able to experience and digital artifacts. identify various aspects of nature through technology. Two of the tools used to make these connections with nature are the Nikon CoolPix L610 Camera and the Age level: IPad. These tools are designed to record images on the go as well as assist you in 4th- 12th creating digital artifacts that can be shared. Education Standards: How to: Digital Camera HS-PS4-2 1. Turn on the Camera by pressing the on/off button. Success Indicator: 2. The camera should be set to “easy-auto” mode, this will allow for the Youth will be able to record their easiest use of the camera. experiences through images and 3. To record an image simply press down on the big silver button on the top videos, as well as create collages, until a green rectangle appears in the middle of the screen. This will auto movies and trailers to share their focus the image. Once the green rectangle appears press down hard to take experience with others. a picture. 4. To change mode, such as landscape or portrait, press the green camera Preparation icon to the right of the screen and the toggle through the different options. 5. To record a video press the black button with the red circle in the middle. Time: This will start taking a video. -

With Dada and Pop Art Influence

With Dada and Pop Art Influence The non-art movement • 1916-1923 • Reaction to the horror of World War I • Artists were mostly French and German. They took refuge in neutral Switzerland. • They were angry at the European society that had allowed the war to happen. • Dada was a form of protest. • It’s intention was to provoke and shock The name “Dada” was chosen because it was nonsensical. They wanted a name that made the least amount of sense. • They used any public forum to spit on: nationalism rationalism materialism and society in general Mona Lisa with a Mustache “The Fountain” “The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even” George Groz “Remember Uncle Augustus the Unhappy Inventor”(collage) Raoul Hausmann “ABCD” (collage) Merit Oppenheim “Luncheon in Fur” Using pre-existing objects or images with little or no transformation applied to them Artist use borrowed elements in their creation of a new work • Dada self-destructed when it was in danger of becoming “acceptable.” • The Dada movement and the Surrealists have influenced many important artists. Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) became one of the most famous artists to use assemblage. His work is both surreal and poetic. A 3-D form of using "found" objects arranged in such a way that they create a piece of art. The Pop American artist, Robert Rauschenberg, uses assemblage, painting, printmaking and collage in his work. He is directly influenced by the Dada-ists. “Canyon” “Monogram” “Bed” “Coca-cola Plan” “Retroactive” • These artist use borrowed elements in their creation to make a new work of art! • As long as those portions of copyrighted works are used to create a completely new and different work of art it was OK. -

Tapestry Translations in the Twentieth Century: the Entwined Roles of Artists, Weavers, and Editeurs

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 Tapestry Translations in the Twentieth Century: The Entwined Roles of Artists, Weavers, and Editeurs Ann Lane Hedlund University of Arizona, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Hedlund, Ann Lane, "Tapestry Translations in the Twentieth Century: The Entwined Roles of Artists, Weavers, and Editeurs" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 462. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/462 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Tapestry Translations in the Twentieth Century: The Entwined Roles of Artists, Weavers, and Editeurs Ann Lane Hedlund The Gloria F. Ross Center for Tapestry Studies Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona, Tucson [email protected] Historically, European tapestry making involved collaboration among artists, designers, draftsmen, cartoon makers, spinners, dyers, weavers, patrons, dealers, and other professionals. This specialized system of labor continued in modified form into the twentieth century in certain European and American weaving workshops. In contrast and with a small number of exceptions, American tapestry in the last half of the twentieth century has centered on weaver-artists working individually in their studios from their own designs. This paper focuses, in a very preliminary way, on one exceptional example of continuity, or revival, of the European specialized labor system—the creation of a group of twentieth century tapestries orchestrated by editeur Gloria F. -

Art Matters Lesson Plan Art Play Lesson #3: Pattern & Colored

Art Matters Lesson Plan Art Play Lesson #3: Pattern & Colored Paper Collage Shelly Korte & Vashti B Moss 4/14/2020 Tools Materials scissors (optional) Colored paper (tissue paper, magazine Table cover (optional) pages, and/ or construction paper) Heavy cardboard glue stick plain white paper (cardstock, mixed media paper, or printer paper) Wet wipes Inspired by: Ramona Sakiestewa, contemporary New Mexican Hopi American tapestry and paper artist. Facets/4, dyed and woven wool. 50in x 90in, currently in the Common Ground collection in Albuquerque Museum. https://ramonasakiestewa.com/artwork/ Set Up 1. Cover work area with tarp or spare paper sheets 2. Each artist will have 2-3 sheets of white paper, a selection of colored paper, and a glue stick Instructions Part 1: Relax and Share a. As a group, take a deep breath through your nose and exhale or sigh out of your mouth. Do this two more times as a group. As you relax your shoulders, your face, and your mind, come into the present moment. b. Check in with how you’re feeling and give it a shape and color. If you’re in a group, go around and give everyone a chance to say this out loud. Part 2: Warm-up/Illustrating Words with Shape and Pattern a. Take a deep breath. Relax your shoulders, your arms, your hands. Remember to pause and do this periodically as you work. b. Students artists will tear (or cut) paper into shapes. Considering color, the grain/tearability of the paper. Notice how it feels to tear the paper. Notice how it feels to change tear direction and method. -

Ovidiu Solcan Collage Artist RO&US.Cdr

OVIDIU SOLCAN | COLLAGE ARTIST OVIDIU SOLCAN COLLAGE ARTIST Ovidiu Solcan is the creator of spectacular carefully designed pop-art collages, in which, at a closer look, one can discover interesting details that might escape an inattentive glance. Ovidiu was born in 1983 in the comunist Bucharest, Romania, where he lived and studied architecture. His passion for art started at an early age but the University of Architecture influenced him to start producing recycled magazine collages as a step forward from his previous mix media artworks (digital, graffiti and acrylic). The result was so exciting that, ever since, he has been more fascinated by the torn pieces of paper than paints. Artworks of great architects like Le Corbusier and Friedensreich Hundertwasser were the starting point of his inspiration for his collage art technique as a personal manner to express his visual concepts. He enjoys working with nothing but recycled magazines and all pieces are manually tear or cut apart and glued to the canvas. @ovidiu.solcan has a large audience on Instagram – one of his major ways of exposing his art. As in real life Ovidiu’s artworks have been shown in exhibitions like: - ARTWALK STREET FESTIVAL – Bucharest 2017 & 2018 - North Sea Jazz Festival Rotterdam 2019 - #Brancusi heARTbeat #5th Edition @ Qreator Bucharest 2019 & 2020 - MONEY GO ROUND – Rosso Gallery 2020 – Rome - Luxury The Concept Store 2020 – Hamburg - Pavot Gallery 2020 – Bucharest Ovidiu had a solo studio gallery where his creative process was exhibited live as an installation at The Grand Avenue – Marriott in March - August 2018. During 2019 Ovidiu had a project sharing the joy of collage creation in partnership with Mastercard and Daruieste Viata Association. -

How to Make a Collage 4 Free Mixed Media Collage Techniques Presented by Cloth Paper Scissors®

how to make a collage 4 free mixed media collage techniques presented by cloth paper scissors® 1 3 4 2 collage to order: objects of my desire: 1 create with words 3 making sewn paper SUSAN BLACK collage collections JENNY COCHRAN LEE the elements of collage: 2 putting it all together reverse collage painting: NICOLE PAISLEY MARTENSEN 4 a bright spot on a winter day HOLLY CHRISTINE MOODY In “Objects of My Desire: Making Sewn Paper Collage Collections,” Jenny Cochran Lee explores how to How to Make a Collage: turn paper scraps into collage art 4 Free Mixed Media treasures. Collage Techniques presented by Finally, Holly Christine Moody Cloth Paper Scissors® offers an easy collage project that ONLINE EDITOR Cate Prato will help you whittle down your decorative paper stash in a fun CREATIVE SERVICES way. In “Reverse Collage Painting,” DIVISION ART DIRECTOR Larissa Davis PHOTOGRAPHER Larry Stein you make a paper collage on a substrate, apply gel medium, Projects and information are for inspiration and personal use only. Interweave Press is not responsible hat is collage art? A and then paint over it. The magic for any liability arising from errors, omissions, or whole lot of fun! At happens when you swipe away mistakes contained in this eBook, and readers should proceed cautiously, especially with respect to technical the most basic level, some of the paint to reveal the information. wyou can make a collage with paper, collage designs below. © F+W Media, Inc. All rights reserved. F+W Media glue, and a substrate like a canvas grants permission for any or all pages in this eBook to With How to Make a Collage: 4 Free or watercolor paper. -

Picture Collage with Genetic Algorithm and Stereo Vision

IJCSI International Journal of Computer Science Issues, Vol. 8, Issue 4, July 2011 ISSN (Online): 1694-0814 www.IJCSI.org 1 Picture Collage with Genetic Algorithm and Stereo vision Hesam Ekhtiyar1, Mahdi Sheida2 and Mahmood Amintoosi3 1 Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Sabzevar Tarbiat Moallem University, Sabzevar, Iran, [email protected] 2 Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Sabzevar Tarbiat Moallem University, Sabzevar, Iran, [email protected] 3 Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science, Sabzevar Tarbiat Moallem University, Sabzevar, Iran, [email protected] Abstract In this paper, a salient region extraction method for creating picture collage based on stereo vision is proposed. Picture collage is a kind of visual image summary to arrange all input images on a given canvas, allowing overlay, to maximize visible visual information. The salient regions of each image are firstly extracted and represented as a depth map. The output picture collage shows as many visible salient regions (without being overlaid by others) from all images as possible. A very efficient Genetic algorithm is used here for the optimization. The experimental results showed the superior performance of the proposed method. Fig. 1 LEFT IMAGES OF SOME STEREO IMAGES USED IN THIS PAPER. Keywords: Picture Collage, Image Summarization, Depth Map visible or the images are occluded, the importance of 1. Introduction regions are discarded. An approach named saliency-based visual attention model Detection of interesting or ”salient” regions is a main sub- [2] is used in [1] for extracting interesting regions. This problem in the context of image tapestry and photo model combines multi scale image features (color, texture, collage. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0337418 A1 Anuradha (43) Pub

US 2013 0337418A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0337418 A1 Anuradha (43) Pub. Date: Dec. 19, 2013 (54) PROCESS OF FLORAL BOTANICAL (52) U.S. Cl. COLLAGE DECOUPAGE CPC ........................................ B44C5/06 (2013.01) USPC ............................................................ 434/93 (76) Inventor: Sahu Anuradha, Chhattisgarh (IN) (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 14/000,229 An improved process for dry flower craft which comprises cutting craft media (dry botanicals with stencils) and mount (22) PCT Filed: Apr. 25, 2011 ing the same on any Surface of product with combination of other botanical elements like bamboo, grass, weeds, seed, (86). PCT No.: stem, tendrils, fiber, Solawood in any desired manner includ S371 (c)(1), ing artistic manner, which comprises reducing color loss Aug. 19, 2013 while drying and storage of vegetation and also during craft (2), (4) Date: ing of the vegetation, making stencils of cheapest materials (30) Foreign Application Priority Data Such as cardboard and paper, cutting out motifs; shaping the petals in any desired shape, pasting the same with known Mar. 9, 2011 (IN) ............................. 3O3AKOLF2011 adhesives, characterized in that botanicals are dried prior to floral collage decoupage by drying while using mixture des iccant of silica gel--silver sand--non iodised salts (1:1:1 ratio), Publication Classification finally obtaining floral decoupage or only floral collage or a combination of bothin design processing as application of the (51) Int. Cl. craft, making the floral resin laminates by reducing the per B44C5/06 (2006.01) oxide harder by 1%. US 2013/0337418 A1 Dec. 19, 2013 PROCESS OF FLORAL BOTANCAL (i) cutting craft media (dry botanicals) by hand with card COLLAGE DECOUPAGE paperstencils and mounting the same on any Surface of prod uct with combination of other botanical elements like bam FIELD OF INVENTION boo, grass, weeds, seeds, stem, tendrils, fiber, Solawood in any desired manner including artistic manner; along with 0001. -

The Art of Thinking: Using Collage to Stimulate Scholarly Work Nicola Simmons Brock University, [email protected]

The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 2 7-6-2013 The Art of Thinking: Using Collage to Stimulate Scholarly Work Nicola Simmons Brock University, [email protected] Shauna Daley Brock University Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cjsotl_rcacea Part of the Art Education Commons, Educational Methods Commons, and the Higher Education and Teaching Commons http://dx.doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2013.1.2 Recommended Citation Simmons, Nicola and Daley, Shauna (2013) "The Art of Thinking: Using Collage to Stimulate Scholarly Work," The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning: Vol. 4: Iss. 1, Article 2. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2013.1.2 Available at: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cjsotl_rcacea/vol4/iss1/2 The Art of Thinking: Using Collage to Stimulate Scholarly Work Abstract Integrating the arts into higher education pedagogy provides an opportunity for cultivating rich ideas and high-level thinking, capitalizing on the creativity that every person already possesses and uses (Livingston, 2010). As Newton and Plummer (2009) note “the use of the creative arts as pedagogical strategy enables individuals to better understand themselves, [and] to stimulate thinking” (p. 75). We extend that premise to examine the impact of an arts activity on scholarly thinking. Our exploratory study examines academics’ (graduate students and educators) identity and role constructs (Kelly, 1955) to understand to what extent engaging in arts-based activities supports meaning-making and conceptualizing research questions. We asked participants to reflect on collages they created, how the collage process supported their research conceptualization, challenges they encountered, and their overall reflections on the process as an adjunct to written scholarly work. -

Botanical Crafts: an Annotated List of References

PLANT BIBLIOGRAPHY JANUARY 1983 Number 4 BOTANICAL CRAFTS: AN ANNOTATED LIST OF REFERENCES Eileen K. Schofield Associate Editor Agricultural Experiment Station Kansas State University Manhattan, KS 66506 The Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries, Inc. ~ The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York 10458 CO Editor: Charles R. Long The New York Botanical Garden Bronx, New York 10458 Correspondence regarding submission of manuscripts for publication may be addressed to the Editor. For ordering copies and requesting a complete list of available bibliographies, please write to The Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries, The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York 10458. Copyright © 1983 by The Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries, Inc. BOTANICAL CRAFTS: AN ANNOTATED LIST OF REFERENCES Eileen K. Schofield Associate Editor Agricultural Experiment Station Kansas State University Manhattan, KS 66506 INTRODUCTION The use of natural materials in crafts has a long history. Flowers were dried (probably in sand) by the ancient Egyptians and in India. Instructions for sand drying were published in Italy in the early 1600's. This remained the best medium for three-dimensional drying until experiments with other agents in the 1940's. Borax and cornmeal were favored for about twenty years, then came the development of the silica gel method. Now a special, fine grade of gel is manufactured just for flowers and it gives nearly foolproof results. Air dried grasses were used for decorations by the Greeks and Romans. The popular everlasting flower (Helichrysum) may have been known to the Egyptians and was mentioned in writing by Dioscorides. Early English gardening books suggest flowers to dry, such as globe amaranth. -

Torrance Public Library Presents: Button Moon Collage “Take and Make” Adult Craft Create a Unique Moon Picture Using Card S

Torrance Public Library Presents: Button Moon Collage “Take and Make” Adult Craft Create a unique moon picture using card stock, a label to create a sticky area, and a variety of buttons. Celebrate International Observe the Moon Night Supplies Provided: on September 26, 2020 Paper with moon outline by making Moon Art using this craft kit! Full page label sheet Buttons and sequins NASA invites you to learn You Will Need to more about lunar science and Provide: our connection to the moon in Scissors & Pencil this worldwide event. For more ways to participate safely from home visit: https://moon.nasa.gov/observe CAUTION 3 THE LABEL IS VERY STICKY. BE CAREFUL NOT TO PLACE STICKY 1 2 SIDE ON TABLE. ONCE PLACED, IT CANNOT BE MOVED. 4 Placing the label white side down, remove one corner of the backing from the label. CAREFULLY place the black Cut out the moon shape Trim the edges of the label paper on top of the sticky printed on the black card- so it is smaller than the label starting in one corner. Slowly remove the rest of stock paper. black paper, but will cover the label backing and press the moon cutout. (Save black paper down on the these strips to make stars) sticker. 5 6 7 8 Create stars by drawing Create a design of large and them on the backing side of small buttons. Add some of the extra label strips. Cut Begin adding buttons to the your own buttons or beads. Enjoy your moon picture! out the stars, peel off the sticky area covering the moon. -

Issue12.10-1.11.Pdf

A View From The Top Greg Busceme, TASI Director IT HAS BEEN A busy month for The Art these dedicated people do is indispensible Studio and promises to continue to be so for a healthy prospect for their clients. well into December. TAN, we love you! Along with our usual November fare, We are attempting to start life drawing we also hosted part of the Gulf Print Storm again. Anyone interested can meet with us Nov. 19, exhibiting the steamroller print on Wednesdays at The Studio, from 6-8 ISSUE Vol. 17, No. 4 and work from the guest artists in the p.m. for life drawing. There is no instruc- workshop. We at The Studio wish to thank tor so you need some basic background in Publisher . The Art Studio, Inc. the generosity of our November exhibitor, drawing, but don’t be intimidated — none Lief Anson Wallace who selflessly allowed of us are THAT good!! Editor . Andy Coughlan his show to come down for this special We also are on the search for models Copy Editor . Tracy Danna event. Lief’s work returned to the walls the to pose for the class. You must be 18 or Contributing Writers . Lluvia Rueda following day. It is cooperation like this older and be able to sit still for 20 minutes . Chelsea Henderson, Jeff Dixon, . Elena Ivanova that is the backbone of Studio life. while we draw. We are not particular about Contributing Photographer. Chelsea Henderson For lack of a place for Band Nite to be size or shape or age, just that you arrive Distribution Director .