India Wood and Wood Products Update 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tectona Grandis Teak

Tectona grandis Teak Family: Verbenaceae Other Common Names: Kyun (Burma), Teck (French). Teca (Spanish). Distribution: Native to India, Burma, Thailand, Indochina, including Indonesia, particularly Java. Extensively cultivated in plantations within its natural range as well as in tropical areas of Africa and Latin America. The Tree On favorable sites, may reach 130 to 150 ft in height with clear boles to 80 to 90 ft; trunk diameters usually 3 to 5 ft; older trees fluted and buttressed. The Wood General Characteristics: Heartwood dark golden yellow, turning a dark brown with exposure, often very variable in color when freshly machined showing blotches and streaks of various shades; sapwood pale yellowish, sharply demarcated. Grain straight, sometimes wavy; texture coarse, uneven (ring porous); dull with an oily feel; scented when freshly cut. Dust may cause skin irritations. Silica content variable, up to 1.4% is reported. Weight: Basic specific gravity (ovendry weight/green volume) 0.55; air-dry density 40 pcf. Mechanical Properties: (First set of data based on the 2-cm standard; second and third sets on the 2-in. standard; third set plantation-grown in Honduras.) Moisture content Bending strength Modulus of elasticity Maximum crushing strength Psi 1,000 psi Psi Green (/7) 12,200 1,280 6.210 11% 15,400 1.450 8.760 Green (38) 10.770 1.570 5.470 14% 12,300 1.710 6.830 Green (81) 9.940 1.350 4.780 13% 13.310 1,390 6.770 Janka side hardness 1,000 to 1,155 lb for dry material. Forest Products Laboratory toughness 116 in.-lb average for green and dry wood (5/8-in. -

Code of Practice for Wood Processing Facilities (Sawmills & Lumberyards)

CODE OF PRACTICE FOR WOOD PROCESSING FACILITIES (SAWMILLS & LUMBERYARDS) Version 2 January 2012 Guyana Forestry Commission Table of Contents FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Wood Processing................................................................................................................................. 8 1.2 Development of the Code ................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Scope of the Code ............................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Objectives of the Code ...................................................................................................................... 10 1.5 Implementation of the Code ............................................................................................................. 10 2.0 PRE-SAWMILLING RECOMMENDATIONS. ............................................................................................. 11 2.1 Market Requirements ....................................................................................................................... 11 2.1.1 General .......................................................................................................................................... -

Regulation on Forest Products Processing and Marketing

Forestry Development Authority Regulation No. 112-08 Regulation on the Forest Products Processing and Marketing WHEREAS, the National Forestry Reform Law of 2006 establishes a transparent framework, for the use, management and protection of forest resources that balances the commercial, community, and conservation priorities of the Republic; and WHEREAS, the economic potential of processed wood products has not been appreciated, there has been too much exportation of crude round logs with evidence of low percentage of primary processed wood for both domestic and export market, no value-added wood product, low recovery rate of wood processing industry, problem of waste disposal; and WHEREAS, industrialization of the wood industry in general and the processing of wood into secondary/value-added products in particular are essential elements for the realization of the potential sustainable utilization of Liberia‘s forest resources; and WHEREAS, sustainable utilization of forest resources concept is not only to maintain the value of forest resources, but rather it also has a huge potential for creating employment, income and wealth for the Liberia populations; and WHEREAS, local small-scale wood enterprises are not fully capacitated and unregulated which in essence has resulted into unsustainable use and marketing of wood products, wastage of wood products, constant exposure of wood products to deteriorating agents; and WHEREAS, the lack of standard units of measurement for Liberia domestic wood market and unregulated import of wood products, -

Urban Wood and Traditional Wood

FNR-490-W AGEXTENSIONRICULTURE Authors Daniel L. Cassens, Professor of Wood Products and Extension Urban Wood and Traditional Wood: Specialist, Purdue University Edith Makra, Chairman, A Comparison of Properties and Uses Illinois Emerald Ash Borer Wood Utilization Team Trees are cultivated in public and private wood. This publication describes some key landscapes in and around cities and differences between wood products from towns. They are grown for the tremendous traditional forests and those available from contributions they make both to the urban forests. Because the urban wood environment and the quality of people’s lives. industry is emerging and the knowledge In this urban forest, trees must be removed base is still sparse, conclusions drawn in the when they die or for reasons of health, safety, publication are based on knowledge of urban or necessary changes in the landscape. The forestry and of the traditional forest products wood from these felled landscape trees industry. could potentially be salvaged and used to manufacture wood products, but not in the Forest Management same way as forest-grown trees. Traditional forests are either managed specifically to produce commodity wood or The traditional forest products industry is to meet stewardship objectives compatible based on forest-grown trees; its markets with responsible harvesting, such as for and systems don’t readily adapt to this new watershed and wildlife. Harvesting is source of urban wood. The urban forest typically done in accordance with long-term grows different trees in a different manner forest management plans that sustain forest than the traditional forest, and the wood health and suit landowner objectives. -

Endemic Philippine Teak (Tectona Philippinensis Benth. & Hook

RESEARCH ARTICLES Endemic Philippine teak (Tectona philippinensis Benth. & Hook. f.) and associated flora in the coastal landscapes of Verde Island Passage, Luzon Island, Philippines Anacleto M. Caringal1,2, Inocencio E. Buot, Jr2,3,4,* and Elaine Loreen C. Villanueva3 1Batangas State University–Lobo, Lobo, Batangas, Philippines 2School of Environmental Science and Management, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines 3Institute of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines 4Faculty of Management and Development Studies, University of the Philippines Open University, Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines deciduous forests, pines, lower and upper montane forests The Philippine teak forest (PTF) is a formation with the Endangered Tectona philippinensis Benth. & Hook. and sub-alpine) based on the dominant floristic elements f., Lamiaceae – an endemic tree flora in the Batangas have been the focus of ecological classification since Province along the Verde Island Passage, Luzon 1900s (refs 13–16). The Philippine teak forest (PTF), Island, Philippines. In this study, we determine the however, has not yet been included in these national general floristic composition of PTF. Vegetation anal- classifications. ysis across coastal to inland continuum generated the The forest with endemic Tectona philippinensis Benth. data for general floristic richness, growth structure & Hook. f., (APG: Lamiaceae) has long been considered and diversity indices. A total of 128 species under 111 as one of the most important areas of floristic genera in 48 families was recorded with overall plant richness10,17,18. Until the present study, however, PTF diversity of very low to moderate (Shannon–Wiener: remains to be classified among the major forest ecotypes 0.8675–2.681). -

Bioresources.Com

PEER-REVIEWED ARTICLE bioresources.com EVALUATION AND IDENTIFICATION OF WALNUT HEARTWOOD EXTRACTIVES FOR PROTECTION OF POPLAR WOOD Seyyed Khalil Hosseini Hashemi a,* and Ahmad Jahan Latibari a Walnut (Juglans regia L.) heartwood extractives were identified and their potential for protection of poplar wood was evaluated. Test specimens were prepared from poplar wood (Populus nigra L.) to meet BS 838:1961 requirements. Samples were impregnated with heartwood extractive solution (1.5, 2.5, and 3.5% w/w in ethanol-toluene), followed by 5 hours vacuum desiccator technique to reach complete saturation. Impregnated specimens were exposed to white-rot fungus (Trametes versicolor) for 14 weeks according to BS 838:1961 applying the kolle- flask method. The weight loss of samples was determined after exposure to white-rot fungus. The highest weight loss (36.96%) was observed for untreated control samples and the lowest weight loss (30.40%) was measured in samples treated with 1.5% extractives solution. The analyses of the extracts using GC/MS indicated that major constituents are benzoic acid,3,4,5-tri(hydroxyl) and gallic acid (44.57 %). The two toxic components in the heartwood are juglone (5.15 %) and 2,7- dimethylphenantheren (5.81 %). Keywords: Walnut heart wood extractives; Trametes versicolor; Weight loss; Gallic acid; Juglone; 2,7- dimethylphenantheren Contact information; a: Agriculture Research Center, Islamic Azad University, Karaj Branch, P. O. Box 331485-313, Karaj, Iran. * Corresponding author: [email protected] INTRODUCTION One of the promising strategies to slow down the decay and deterioration of wood structure is to rely upon durable wood species. -

Wood As a Sustainable Building Material Robert H

CHAPTER 1 Wood as a Sustainable Building Material Robert H. Falk, Research General Engineer Few building materials possess the environmental benefits of wood. It is not only our most widely used building mate- Contents rial but also one with characteristics that make it suitable Wood as a Green Building Material 1–1 for a wide range of applications. As described in the many Embodied Energy 1–1 chapters of this handbook, efficient, durable, and useful wood products produced from trees can range from a mini- Carbon Impact 1–2 mally processed log at a log-home building site to a highly Sustainability 1–3 processed and highly engineered wood composite manufac- tured in a large production facility. Forest Certification Programs 1–3 As with any resource, we want to ensure that our raw ma- Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) 1–4 terials are produced and used in a sustainable fashion. One Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) 1–4 of the greatest attributes of wood is that it is a renewable resource. If sustainable forest management and harvesting American Tree Farm System (ATFS) 1–4 practices are followed, our wood resource will be available Canadian Standards Association (CSA) 1–5 indefinitely. Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) Schemes 1–5 Wood as a Green Building Material Over the past decade, the concept of green building1 has Additional Information 1–5 become more mainstream and the public is becoming aware Literature Cited 1–5 of the potential environmental benefits of this alternative to conventional construction. Much of the focus of green building is on reducing a building’s energy consumption (such as better insulation, more efficient appliances and heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems) and reducing negative human health impacts (such as con- trolled ventilation and humidity to reduce mold growth). -

Energy Efficiency Measures in the Wood Manufacturing Industry

Energy Efficiency Measures in the Wood Manufacturing Industry B. Gopalakrishnan, A. Mate, Y. Mardikar, D.P. Gupta and R.W. Plummer, West Virginia University, Industrial Assessment Center B. Anderson, West Virginia University, Division of Forestry ABSTRACT The objectives of the research are to examine the energy utilization profile of the wood manufacturing industry with respect to system level production parameters and investigate the viability of specific energy efficiency measures. The Industrial Assessment Center (IAC) has conducted energy assessments in the wood manufacturing industrial sector in the State for several years. The energy utilization profile of several wood processing facilities is analyzed and reported. The production system parameters in terms of throughput and nature of manufacturing operations are examined in relation to the overall energy utilization, specific energy consumption, and potential for implementation of energy efficiency measures (EEM). Introduction Energy management is the application of engineering principles to the control of energy costs at a facility. It is a continuous process that requires consistent efforts for identifying potential areas for conservation, formulation of proposals and implementation. There are many energy efficient technologies and practices, both currently available and under development, that could save energy if adopted by industry. Energy and energy management have been in the limelight in various manufacturing and service operations across the industries in the US. Although large quantities of wood are utilized as fuel, pulpwood, and railroad ties, lumber is by far the most important form in which wood is used. In the US, the volume of wood converted into lumber exceeds the volume used for all other purposes. -

Cost-Efficient Production in the Wood- Working and Wood Processing

Cost-efficient production in the wood- working and wood processing industry Source: Homag Group AG The production processes in your industry are as varied as the natural raw material, wood. Machines with innovative automation technology bring about crucial cost advantages here. Benefit from a competitive advantage Festo’s core business includes applied automation technology for a wide variety of machines, from entry- level to fully automated high-end ones. A key technological feature of our solutions is pneumatics as a sturdy and low-cost medium. It has long established itself as the standard for primary woodworking and secondary wood processing in wood-based products technology, sawing or planing technology as well as in production machines and plants for furniture production, the components industry and carpentry and joinery. Discover new dimensions for your company. We will help you to achieve your goals, because cost optimisation, maximum productivity, global presence and close partnerships with our customers are the hallmarks of Festo. Source: Homag Group AG Large number of standard products suitable for the working space and resistant to dust and chips Complemented by an industry-specific product offer and application-optimised solutions Global network of specialists for on-site support Consistent quality of products and services – worldwide Long-term, reliable partnership You have high standards, we ensure you meet them The company nobilia with around 3,000 employees production, it supplies almost one in three kitchens has been exclusively producing its products in sold throughout Germany, employing a high level Germany for 70 years. The two plants in Verl in of automation to guarantee a constant level of East Westphalia are among the most modern and quality. -

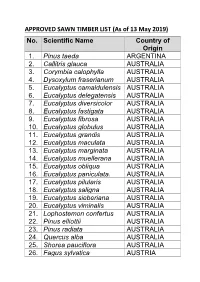

APPROVED SAWN TIMBER LIST (As of 13 May 2019) No. Scientific Name Country of Origin 1

APPROVED SAWN TIMBER LIST (As of 13 May 2019) No. Scientific Name Country of Origin 1. Pinus taeda ARGENTINA 2. Callitris glauca AUSTRALIA 3. Corymbia calophylla AUSTRALIA 4. Dysoxylum fraserianum AUSTRALIA 5. Eucalyptus camaldulensis AUSTRALIA 6. Eucalyptus delegatensis AUSTRALIA 7. Eucalyptus diversicolor AUSTRALIA 8. Eucalyptus fastigata AUSTRALIA 9. Eucalyptus fibrosa AUSTRALIA 10. Eucalyptus globulus AUSTRALIA 11. Eucalyptus grandis AUSTRALIA 12. Eucalyptus maculata AUSTRALIA 13. Eucalyptus marginata AUSTRALIA 14. Eucalyptus muellerana AUSTRALIA 15. Eucalyptus obliqua AUSTRALIA 16. Eucalyptus paniculata. AUSTRALIA 17. Eucalyptus pilularis AUSTRALIA 18. Eucalyptus saligna AUSTRALIA 19. Eucalyptus sieberiana AUSTRALIA 20. Eucalyptus viminalis AUSTRALIA 21. Lophostemon confertus AUSTRALIA 22. Pinus elliottii AUSTRALIA 23. Pinus radiata AUSTRALIA 24. Quercus alba AUSTRALIA 25. Shorea pauciflora AUSTRALIA 26. Fagus sylvatica AUSTRIA No. Scientific Name Country of Origin 27. Picea abies AUSTRIA 28. Picea abies BELARUS 29. Pinus sylvestris BELARUS 30. Quercus alba BELGIUM 31. Dipteryx odorata BOLIVIA 32. Apuleia leiocarpa BRAZIL 33. Astronium lecointei BRAZIL 34. Bagassa guianensis BRAZIL 35. Cedrela odorata BRAZIL 36. Cedrelinga catenaeformis BRAZIL 37. Couratari guianensis BRAZIL 38. Dipteryx odorata BRAZIL 39. Eucalyptus grandis BRAZIL 40. Eucalyptus grandis BRAZIL 41. Hymenaea courbaril BRAZIL 42. Hymenolobium modestum BRAZIL 43. Hymenolobium Nitidum BRAZIL Benth 44. Hymenolobium BRAZIL pulcherrimum 45. Manilkara bidentata BRAZIL 46. Myroxylon balsamum BRAZIL 47. Pinus radiata BRAZIL 48. Pinus taeda BRAZIL 49. Quassia simarouba BRAZIL 50. Tectona grandis BRAZIL 51. Fagus sylvatica BULGARIA No. Scientific Name Country of Origin 52. Quercus alba BULGARIA 53. Chlorophora excelsa CAMEROON 54. Cylicodiscus gabunensis CAMEROON 55. Entandrophragma CAMEROON candollei 56. Entandrophragma CAMEROON cylindricum 57. Entandrophragma CAMEROON cylindricum 58. Entandrophragma utile CAMEROON 59. -

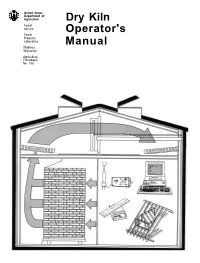

Dry Kiln Operator's Manual

United States Department of Agriculture Dry Kiln Forest Service Operator's Forest Products Laboratory Manual Madison, Wisconsin Agriculture Handbook No. 188 Dry Kiln Operator’s Manual Edited by William T. Simpson, Research Forest Products Technologist United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory 1 Madison, Wisconsin Revised August 1991 Agriculture Handbook 188 1The Forest Products Laboratory is maintained in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. This publication reports research involving pesticides. It does not contain recommendations for their use, nor does it imply that the uses discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. CAUTION, Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife-if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for the disposal of surplus pesticides aand pesticide containers. Preface Acknowledgments The purpose of this manual is to describe both the ba- Many people helped in the revision. We visited many sic and practical aspects of kiln drying lumber. The mills to make sure we understood current and develop- manual is intended for several types of audiences. ing kiln-drying technology as practiced in industry, and First and foremost, it is a practical guide for the kiln we thank all the people who allowed us to visit. Pro- operator-a reference manual to turn to when questions fessor John L. Hill of the University of New Hampshire arise. It is also intended for mill managers, so that they provided the background for the section of chapter 6 can see the importance and complexity of lumber dry- on the statistical basis for kiln samples. -

A Guide to Lesser Known Tropical Timber Species July 2013 Annual Repo Rt 2012 1 Wwf/Gftn Guide to Lesser Known Tropical Timber Species

A GUIDE TO LESSER KNOWN TROPICAL TIMBER SPECIES JULY 2013 ANNUAL REPO RT 2012 1 WWF/GFTN GUIDE TO LESSER KNOWN TROPICAL TIMBER SPECIES BACKGROUND: BACKGROUND: The heavy exploitation of a few commercially valuable timber species such as Harvesting and sourcing a wider portfolio of species, including LKTS would help Mahogany (Swietenia spp.), Afrormosia (Pericopsis elata), Ramin (Gonostylus relieve pressure on the traditionally harvested and heavily exploited species. spp.), Meranti (Shorea spp.) and Rosewood (Dalbergia spp.), due in major part The use of LKTS, in combination with both FSC certification, and access to high to the insatiable demand from consumer markets, has meant that many species value export markets, could help make sustainable forest management a more are now threatened with extinction. This has led to many of the tropical forests viable alternative in many of WWF’s priority places. being plundered for these highly prized species. Even in forests where there are good levels of forest management, there is a risk of a shift in species composition Markets are hard to change, as buyers from consumer countries often aren’t in natural forest stands. This over-exploitation can also dissuade many forest willing to switch from purchasing the traditional species which they know do managers from obtaining Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification for the job for the products that they are used in, and for which there is already their concessions, as many of these high value species are rarely available in a healthy market. To enable the market for LKTS, there is an urgent need to sufficient quantity to cover all of the associated costs of certification.