ACTING SHAKESPEARE: a Roundtable Discussion with Artists from the Utah Shakespeare Festival’S 2013 Production of the Tempest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Shakespeare Festival Production History = 1990S 1991

Oregon Shakespeare Festival Production History = 1990s 1991 saw the retirement of Jerry Turner, and the appointment of Henry Woronicz as the third Artistic Director in the Festivals 56 year history. The year also saw our first signed production, The Merchant of Venice. The Allen Pavilion of the Elizabethan Theatre was completed in 1992, providing improved acoustics, sight-lines and technical capabilities. The Festival’s operation in Portland became an independent theatre company — Portland Center Stage — on July 1, 1994. In 1995 Henry Woronicz announces his resignation and Libby Appel is named the new Artistic Director of the Festival. The Festival completes the canon for the third time in 1997, again with “Timon of Athens.” The Festival’s production of Lillian Garrett-Groag’s The Magic Fire plays at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC from November 10 through December 6, 1998, and is selected by Time Magazine as one of the year’s Ten Best Plays. In this decade the Festival produced these World Premieres, including adaptations: 1990 - Peer Gynt,1993 - Cymbeline, 1995 - Emma’s Child, 1996 - Moliere Plays Paris, 1996 – The Darker Face of the Earth, 1997 - The Magic Fire, 1998 - Measure for Measure, 1999 - Rosmersholm,1999 - The Good Person of Szechuan Year Production Director Playwright Theatre 1990 Aristocrats Killian, Philip Friel, Brian Angus Bowmer Theatre 1990 At Long Last Leo Boyd, Kirk Stein, Mark Black Swan 1990 The Comedy of Errors Ramirez, Tom Shakespeare, William Elizabethan Theatre 1990 God's Country Kevin, Michael Dietz, Steven Angus Bowmer Theatre 1990 Henry V Edmondson, James Shakespeare, William Elizabethan Theatre 1990 The House of Blue Leaves McCallum, Sandy Guare, John Angus Bowmer Theatre 1990 The Merry Wives of Windsor Patton, Pat Shakespeare, William Angus Bowmer Theatre 1990 Peer Gynt Turner, Jerry Ibsen, Henrik Angus Bowmer Theatre 1990 The Second Man Woronicz, Henry Behrman, S.N. -

2009 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Illinois Shakespeare Festival Fine Arts Summer 2009 2009 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/isf Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation School of Theatre and Dance, "2009 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program" (2009). Illinois Shakespeare Festival. 23. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/isf/23 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Fine Arts at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illinois Shakespeare Festival by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Richard III the theatre at ewinrr 0 cultur-ll, center· • I ~ ILLINOIS " SiHAKJESPlEARJE Sponsored by (&HYDER) THE SNYOER COMPANIES FESTIVAl .-1.PAAf~IHS I HOflLS l (NSUFAl,CE l l'l:ALESf.t.TE 7 - 200J ::_ J21!d JCCkfrJf! AMidsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare June 25, 28, 30,July 2, 5, 9, 11, 17, 19, 23, 25, 30, August 2, 4, 8 Scapin by Bill Irwin and Mark O'Donnell, adapted from Jean Baptiste Moliere June 26, 27,July 1, 3, 10, 12, 18, 21, 24, 29, 31, August 6, 9 Richard Ill by William Shakespeare July 16, 22, 26, 28, August 1, 5, 7 DEB ALLEY JOHN POOLE Anistic Director Managing Director The 2009 Illinois Shakespeare Festival is made possible in part by funding and support provided by individuals, businesses, foundations, government agencies, and organizations. -

Jeb Burris Aea, Sag-Aftra

JEB BURRIS AEA, SAG-AFTRA SELECTED THEATRE OTHELLO*** Cassio Kate Buckley Utah Shakespeare Festival THE LIAR*** Dorante Brad Carroll Utah Shakespeare Festival MACBETH** Malcolm Charles Fee Great Lakes Theater THE NETHER Woodnut Kirk Blackinton Capital Stage THE ORIGINALIST Brad James Still Indiana Repertory Theatre AS YOU LIKE IT Orlando Robynn Rodriguez Utah Shakespeare Festival SHAKESPEARE IN LOVE Ned Alleyn Brian Vaughn Utah Shakespeare Festival ROMEO AND JULIET Mercutio J.R. Sullivan Utah Shakespeare Festival LEARNING TO STAY + Brad Sabbatto Jennifer Grey Forward Theater THE TEMPEST Ferdinand B.J. Jones Utah Shakespeare Festival THE THREE MUSKETEERS D’Artagnan Henry Woronicz Indiana Repertory Theatre LOVE’S LABOUR'S LOST Longaville Tyne Rafaeli Great Lakes Theatre LOVE’S LABOUR’S LOST Longaville Tyne Rafaeli Idaho Shakespeare Festival COMEDY OF ERRORS Dromio E. Charles Fee Lake Tahoe Shakespeare THE GAME OF LOVE AND CHANCE Dorante David Frank American Players Theatre THE GLASS MENAGERIE Jim O’Connor J.R. Sullivan Utah Shakespeare Festival PRIDE AND PREJUDICE Wickham Tyne Rafaeli American Players Theatre JULIUS CAESAR Brutus Kirk Blackinton Sacramento Theatre Co. OTHELLO Lodovico John Langs American Players Theatre ROMEO AND JULIET Mercutio Rachel Rockwell Chicago Shakespeare Theatre THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR Pistol Tim Ocel American Players Theatre MACBETH Macbeth Henry Woronicz Illinois Shakespeare Festival MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING Don Pedro David Frank American Players Theatre TRAVESTIES Bennet William Brown American Players Theatre -

Spring 2016 PSF Newsletter

The Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival Newsletter • Spring 2016 West Side Story was not the first, nor the last, musical to be adapted from one of Shakespeare’s plays. The Boys from Syracuse, Kiss Me Kate, Two Gentleman of Verona, and more recently Something’s Rotten were all inspired by the Bard. But no other musical changed the landscape of musical theatre the way West Side did—the music bor- dered on the operatic meshed with a Latin fusion, the lyrics were simple but unforget- table, and the dance was the most exciting, lyrical, and powerful dance ever seen on Broadway. Four geniuses of Jewish descent created this masterpiece and each of them contrib- uted key ingredients to its success: Jerome Robbins who conceived the work, directed and choreographed; Leonard Bernstein, a Harvard-trained composer and world renowned conductor, composed the score; Arthur Laurents, playwright and Hollywood screenwriter, wrote the book, and a young Stephen Sondheim wrote the lyrics. Although Bernstein served as the famous conductor of the New York Philharmonic and was revered in the classi- ‘‘ cal musical world, he may be most remem- bered for the soaring and percussive, jazz- infused music he wrote for West Side Story. Years later Bernstein recalled, “This was one GENIUSES AT WORK of the most extraordinary collaborations of By Dennis Razze my life, perhaps the most, in that very sense of our nourishing one another. There was a generosity on everybody’s part that I’ve The radioactive fallout from West Side Story must rarely seen in the theatre… Without any still be descending on Broadway this morning. -

DOROTHY MARSHALL ENGLIS 831 South Gore

DOROTHY MARSHALL ENGLIS 831 South Gore Avenue St. Louis, MO 63119 314-968-5443 (home) 314-968-6966 (office) 314-753-6854 (cell) E-mail: [email protected] CURRICULUM VITAE PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Webster University, Conservatory of Theatre Arts St. Louis, MO, Faculty member, 1979 – 2003; 2005 to present Department Chair, 2005 to 2020 Full Professor since 1992 Head of Design and Technical Program, 1980 – 2003 Webster University, Director, London Campus (in association with Regent’s College), 2003-2005 Acted as Webster’s onsite representative in managing study , undergraduate, and students in all programs Part of team that negotiated new partner contract between Webster University and Regent’s College Initiated speaker series in International Studies and Business Webster University, President of the Faculty Senate / Chair of the Faculty Executive Committee 1992 – 1998 Presided over conversion of university faculty governance from direct committee election to a representative senate Presided over Webster University’s systemic change from one large body into five academic units Worked in collaboration with three presidents in transition Tulane University, Newcomb College, Department of Theatre and Speech Visiting Assistant Professor, 1977-1979 DEGREES Master of Fine Arts in Costume Design, with honors Carnegie-Mellon University, College of Fine Arts, 1977 MFA Thesis project: KING LEAR by William Shakespeare Bachelor of Arts, magna cum laude in Drama and English Tufts University, Jackson College, 1974 2 PROFESSIONAL MEMBERSHIPS Art Schools Network (non-profit organization formed for art school leaders), Member of the Board of Directors (2010-2016) College to Career Committee Society for Directors and Choreographers, Associate United Scenic Artists, Local 829, Costume Design United States Institute for Theatre Technology (USITT) Costume Commission Association for Theatre in Higher Education (ATHE) AWARDS AND HONORS St. -

2021 AMERICAN PLAYERS THEATRE STUDY GUIDE Cymbeline

Cymbeline 2021 AMERICAN PLAYERS THEATRE STUDY GUIDE Cymbeline By William Shakespeare Adapted by Marti Lyons & Sara Becker From an original adaptation by Henry Woronicz Welcome to APT's Study Guide, created to accompany Student Matinee performances of William Shakespeare's Cymbeline, adapted by Marti Lyons and Sara Becker from an original adaptation by Henry Woronicz. Use it however you see fit - before or after the performance, or any time in between. Multi Media A selection of videos and podcasts featuring Cymbeline artists and experts. Multi Media Thanks to our Major Education Funders With Additional Support From Linda Amacher * Nancy & Dale Amacher * Tom & Renee Boldt * Paul & Susan Brenner * Arch & Eugenia Bryant * Ronni Jones APT Children's Fund at the Madison Community Foundation * Rob & Mary Gooze * Herzfeld Foundation * Orange & Dean Schroeder * Lynda Sharpe Many Thanks! Director: Marti Lyons Voice & Text Coach: Sara Becker Costume Design: Raquel Adorno Scenic Design: Takeshi Kata Co-Lighting Design: Jason Lynch Co-Lighting Design: Keith Parham Co-Lighting Design: Michael A. Peterson Sound Design & Original Music: Mikhail Fiksel Fight Director: Jeb Burris Choreographer: Mollye Maxner Stage Manager: Evelyn Matten Who’s Who in Cymbeline Imogen (Melisa Pereyra) Pisanio (Elizabeth Ledo) King Cymbeline’s daughter. She Posthumus’ servant, he refuses to marries Posthumus, though her obey his master’s order to murder stepmother has promised her to Imogen, and instead leads her to a her own son, Cloten. When refuge in the woods. Posthumus is tricked into questioning her fidelity and plots her murder, she disguises herself as a boy called Fidele. The Queen (Gina Daniels) Cymbeline (Sarah Day) Cymbeline’s second wife, she A pre-Christian King of Britain, he wants her son Cloten to marry is manipulated by his second wife, Imogen with plans to make him and rebels against Rome, causing a king. -

SETTING the SCENE: DIRECTORIAL USE of ANALOGY in TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN SHAKESPEARE PRODUCTIONS by LAWRENCE RONALD TATOM B

SETTING THE SCENE: DIRECTORIAL USE OF ANALOGY IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN SHAKESPEARE PRODUCTIONS by LAWRENCE RONALD TATOM B.A., California State University Sacramento, 1993 M.F.A., University of North Carolina – Greensboro, 1996 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre 2011 This thesis entitled: Setting the Scene: Directorial Use of Analogy in Twentieth-Century American Shakespeare written by Lawrence Ronald Tatom has been approved for the Department of Theatre. _________________________________ Oliver Gerland, Associate Professor __________________________________ James Symons, Professor Date___________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of the scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRC protocol # 0902.28 Tatom, Lawrence Ronald (Ph.D., Theatre) Setting the Scene: Directorial Use of Analogy in Twentieth-Century American Shakespeare Productions. Thesis directed by Associate Professor Oliver Gerland This dissertation charts the historical development of the use of analogy by stage directors in twentieth-century American Shakespeare productions. Directorial analogy, the technique of resetting a play into a new time, place or culture that resembles or echoes the time, place or culture specified by the playwright, enables directors to emphasize particular themes in a play while pointing out its contemporary relevance. As the nineteenth century ended, William Poel and Harley Granville-Barker rejected the pictorial realism of the Victorian era, seeking ways to recreate the actors-audience relationship of the Elizabethan stage. -

To Download the PDF Resume

Joe Payne Composer, Sound and Projection Designer 1848 Stonebrook Dr, Knoxville, TN 37923 • 801-502-7256 • [email protected] • www.paynesound.com Education B.S. in Theatre; emphasis in Sound Technology & Scenic Design, Weber State University 1995 University Employment/Teaching University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN Associate Professor of Sound and Digital Media Design, Department of Theatre 2011-present Illinois State University, Normal, IL Assistant Professor of Sound and Media, School of Theatre 2010-2011 The University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT Clinical Adjunct Faculty, Department of Theatre 2000-2010 Memberships United Scenic Artists local 829, as a Sound Designer, 2003-Present. TSDCA - Theatrical Sound Designers and Composers Association. Central Region Representative 2016-19. USITT - United States Institute for Theatre Technology, Commissioner, Digital Media Commission 2017-Present. OISTAT - International Org. of Scenographers, Theatre Architects, and Technicians Sound Working Group. SETC – Southeastern Theatre Conference. Freelance Composition, Sound, and Projection Design Riverside Theatre, Vero Beach, FL ProJection Design Almost Heaven, John Denver Sherry Lutkin 2020 MarBle City Opera, Knoxville, TN ProJection Design Shadowlight J Marvel/K Frady 2020 Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park ProJection Design Lifespan of a Fact Wendy Goldberg 2019 Sound Design and Composition Sooner/Later Lisa Rothe 2018 Sound Design Native Gardens (world premiere) Blake Robison 2016 Sound and Projection Design Ring of Fire Jason Edwards 2015 Sound Design Pride and Prejudice Blake Robison 2015 Original Music Ten Little Indians John Going 2002 Imagination Stage, Bethesda, MD Sound Design Cinderella Kate Bryer 2018 Sound Design Charlotte’s Web Kate Bryer 2017 Pioneer Theatre Company, SLC, UT (as guest designer) Sound Design and Composition Curious Incident...Dog…Night-Time Karen Azenberg 2017 Syracuse Stage Sound Design and Composition Deathtrap Paul Barnes 2017 Berkeley Rep Sound Design Hand to God David Ivers 2016 Repertory Theatre of St. -

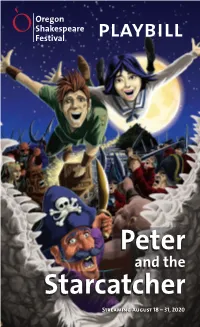

Peterpeter Andand Thethe Starcatcherstarcatcher Streamingstreaming Augustaugust 1818 –– 31,31, 20202020 PHOTO by KIM BUDD

playbill PeterPeter andand thethe StarcatcherStarcatcher StreamingStreaming AugustAugust 1818 –– 31,31, 20202020 PHOTO BY KIM BUDD PASSION. CREATIVITY. PERFORMANCE. A cast of faculty with the highest degrees in their fields, clear paths toward degree completion, and front row seats to AN 2020 our spectacular natural environment. Economical approaches (NOPE) to an excellent educational value. We set the stage for a superb d institution of higher education, located in the tain landscape of southern Oregon, that is an inclu- learning experience. Stop by and take in a performance! or the future that guides all learners to develop the acities, and audacity to innovate boldly and create e. aph (SURE WHY NOT) CHALLENGE ACCEPTED or the Arts at Southern Oregon University serves as ts school as well as a regional arts center, presenting nd contemporary art to the Rogue Valley commu- SOU.EDU | 855-470-3377 nd beyond. Southern Oregon University is home to the Oregon Center for the Arts, proudly bringing music, theatre, and other public events to the Rogue Valley community 2 Go to oca.sou.edu for more information SOU OSF Playbill Ad JAN 2020.indd 1 2/6/20 2:33 PM BELLE FIORE WINERY, ESTATE AND VINEYARD PHOTO BY KIM BUDD Ashland’s Premiere Destination Winery PASSION. CREATIVITY. Pavilion Tasting Room PERFORMANCE. Monday & Tuesday: 12pm-5pm, Wednesday-Sunday: 12pm-8pm *Seasonal hours subject to change. See www.bellefi orewine.com Chateau Tasting Room A cast of faculty with the highest degrees in their fields, Private Tastings at the Chateau. clear paths toward degree completion, and front row seats to AN 2020 our spectacular natural environment. -

Michael Elich Resume 11

MICHAEL ELICH michaelelich.com AEA SAG/AFTRA 541-482-8313 [email protected] THEATRE Oregon Shakespeare Festival (59 roles in 47 productions) Hamlet Claudius Lisa Peterson Great Expectations Jaggers Penny Metropulos The Heart of Robin Hood (American Premiere) Prince John Joel Sass Twelfth Night Feste Darko Tresnjak Troilus and Cressida Thersites Rob Melrose The Pirates of Penzance The Pirate King Bill Rauch The African Co. Presents Richard III Stephen Price Seret Scott She Loves Me Steven Kodaly Rebecca Taichman The Music Man Harold Hill Bill Rauch Coriolanus Aufidius Laird Williamson King John King John John Sipes The Taming of the Shrew Petruchio Kate Buckley Richard III Buckingham Libby Appel Idiot’s Delight Harry Van Peter Amster A Midsummer Night’s Dream Theseus Mark Rucker The Merchant of Venice Antonio Michael Donald Edwards Enter the Guardsman The Actor Peter Amster Trojan Women Poseidon Liz Diamond Cabaret Verboten The Conferencier Penny Metropulos Henry IV, part 1 Hotspur Michael Donald Edwards Nora Torvald Richard E.T. White Awake And Sing! Moe Axelrod Debra Wicks Fifth of July John Landis Clinton Turner Davis Utah Shakespeare Festival Treasure Island (Mary Zimmerman adaptation) Long John Silver Sean Graney Henry VI, part 1 Duke of York Henry Woronicz Shakespeare in Love Burbage Brian Vaughn The Merry Wives of Windsor Dr. Caius Paul Barnes As You Like It Jaques Robynn Rodriguez The Clarence Brown Theatre, TN King Charles III Prime Minister Evans John Sipes Red Mark Rothko John Sipes Hartford Stage Comedy of Errors The Duke/Dr. -

Wayne T. Carr

Wayne T. Carr AFTRA, AEA Eye Color: Black Hair Color: Black Height: 5' 9" [175.26 cm.] TELEVISION S.W.A.T. Co-Star CBS Billy Gierhart Stuck In The Middle Guest Star Disney Channel April Winney Pleading Guilty (Pilot) Co-Star Fox Jon Avnet Matadors (Pilot) Co-Star ABC Yves Simoneau FILM Macbeth Supporting Scott Rudin Productions Joel Coen Who's Afraid of the Big Black Wolf? (Short) Supporting Triglav Film Janez Lapajne THEATRE Macbeth Macbeth Utah Shakespeare Festival Melissa Rain Anderson Othello Othello Utah Shakespeare Festival Kate Buckley Seven Guitars Canewell Yale Repertory Theatre Timothy Douglas Pericles Pericles The Guthrie, Folger, OSF Joe Haj Antony and Cleopatra Pompei Oregon Shakespeare Festival Bill Rauch All the Way Stokley Carmichael Seattle Rep, OSF Bill Rauch Great Society Stokley Carmichael Seattle Rep, OSF Bill Rauch Tempest Caliban Oregon Shakespeare Festival Bill Rauch Taming of the Shrew Lucentio Oregon Shakespeare Festival David Ivers Midsummer's Demetrius Oregon Shakespeare Festival Christopher Liam Moore As You Like It Orlando Oregon Shakespeare Festival Jessica Thebus Funk It Up Cast Joe's Pub, NY Q Brothers Gentrifusion Cast Red Fern, NY Moritz Von Stuelphagel Richard II Duke Aumerle Pearl Theater Co., NYC J.R. Sullivan Bomb-itty of Errors Adriana Hudson Valley Shakespeare Chris Edward Romeo and Juliet Tybalt Indiana Repertory Tim Ocel A Christmas Carol Dick Wilkins The Goodman Kate Buckley Trouble in Mind John Nevins Milwaukee Repertory Timothy Douglas Eurydice Lord of the Underworld Milwaukee Repertory Jonathan Moscone Love's Labour's King of Navarre Milwaukee Shakespeare Jennifer Uphoff Gray Much Ado Don Pedro Nebraska Shakespeare Cindy Phaneuf Fat Pig Carter Renaissance Theaterworks Susan Fete TopDog UnderDog Booth Renaissance Theaterworks Susan Fete Tartuffe Damis American Players Theatre David Frank Julius Caesar Popillius American Players Theatre Sandy Robbins Seussical Wick Brother Fulton Opera House Robin McKercher Joseph.. -

Charles Pasternak AEA [email protected] Artistic Director Designate: Santa Cruz Shakespeare (310) 850-2053

Charles Pasternak AEA [email protected] Artistic Director Designate: Santa Cruz Shakespeare (310) 850-2053 Theatre Credits Murder on the Orient Express Ratchett / Arbuthnot Sierra Repertory Theatre dir. Jerry Lee Hamlet Hamlet Clarence Brown Theatre dir. John Sipes The Man of Destiny Napoleon American Players Theatre dir. James Bohnen The Book of Will Ed Knight American Players Theatre dir. Tim Ocel Macbeth Murderer 2 American Players Theatre dir. James DeVita How I Learned to Drive Greek Chorus Coachella Valley Repertory dir. Joanne Gordon Twelfth Night Orsino Alabama Shakespeare Festival dir. Greta Lambert Romeo and Juliet Mercutio Indiana Repertory Theatre dir. Henry Woronicz A Christmas Carol Fred / Young Scrooge Indiana Repertory Theatre dir. Janet Allen Peter and the Starcatcher Black Stache Clarence Brown Theatre dir. Casey Sams The Winter’s Tale Leontes Shakespeare Festival St. Louis dir. Bruce Longworth The Busy Body Marplot Clarence Brown Theatre dir. John Sipes The Three Musketeers Buckingham Indiana Repertory Theatre dir. Henry Woronicz The Mousetrap Trotter Indiana Repertory Theatre dir. Courtney Sale Titus Andronicus Saturninus Clarence Brown Theatre dir. John Sipes Macbeth Macbeth Sierra Repertory Theatre dir. Dennis Jones Antony and Cleopatra Octavius Shakespeare Festival St. Louis dir. Mike Donahue Much Ado About Nothing Claudio Shakespeare Theatre of NJ dir. Scott Wentworth Two Gentlemen of Verona Valentine Indiana Repertory Theatre dir. Tim Ocel Henry IV Hotspur Shakespeare Festival St. Louis dir. Tim Ocel Henry V the Dauphin Shakespeare Festival St. Louis dir. Bruce Longworth The Merchant of Venice Lorenzo Shakespeare Center of LA dir. Ben Donenberg Henry V Henry V Shakespeare Santa Cruz dir. Paul Mullins Taming of the Shrew the Tailor Shakespeare Santa Cruz dir.