1 Zie-P(Z Center for Economic Policy Research 1 [Stanford University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B. Douglas Bernheim

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES BEQUESTS AS A MEANS OP PAYMENT B. Douglas Bernheim AnclreiShlejfer Lawrence H. Summers Working Paper No. 1303 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 19811 We would like to thank V. Fuchs, M.A. King, J.M.Poterba, R. Vishny, as well as seminar participants at Brown, Harvard, North Carolina State and Stanford for helpful comments. Financial sup-.. portfrom the NSF is gratefully acknowledged. The research reported here is part of the NBER 's researchprogram in Taxation andproject in Pensions. Any opinions expressed are those of the authors and not those of the National Bureau of EconomicResearch. NBER Working Paper #1303 March 1984 Bequests as a Means of Payment ABSTRACT Although recent research suggests that intergenerational transfers play an important role in aggregate capital accumulation, our understanding of bequest motives remains incomplete. We develop a simple model of "exchange—motivated" bequests, in which a testator influences the decisions of his beneficiaries by holding wealth in bequeathable forms and by conditioning the division of bequests on the beneficiaries' actions. The model generates falsifiable empirical predictions which are inconsistent with other theories of intergenerational transfers. We present econometric and other evidence which strongly suggests that bequests are often used as a means of payment for services rendered by beneficiaries. B. Douglas Bernheim Andrei Shleifer Lawrence H. Summers Department of Economics National Bureau of Department of Economics Stanford University Economic Research Littauer Center 229 452 Encina Hall 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Harvard University Stanford, CA 914305 Cambridge, MA 02138 Cambridge, MA 02138 "Tell Ire, try daughters (Since now we will divest us 'both of rule, Interest of territory, cares of state). -

CEPA Center for Economic Policy Research" 1§Panford University

CEPA Cak Atbl /07 Center for Economic Policy Research" 1 1§panford University 1 Discussion Paper Series CEPR This work is distributed as a Policy Paper by the CENTER FOR ECONOMIC POLICY RESEARCH CEPR Publication No. 101 SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND ECONOMIC GROWTH by .:,!Awarzt a;--3131;c7;t77,01*-1 CCULTURAL49NOMICS Nathan Rosenberg r./ORARY Department of Economics Stanford University JUL 01989 February 1987 Center for Economic Policy Research 100 Encina Commons Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305 (415) 725-1874 This paper has been prepared for presentation at the 1987 Annual meeting of the AAAS, Chicago, 14 February 1987. The Center for Economic Policy Research at Stanford University supports research bearing on economic and public policy issues. The CEPR Discussion Paper Series reports on research and policy analysis conducted by researchers affiliated with the Center. Working papers in this series reflect the views of the authors and not necessarily those of the Center for Economic Policy Research or Stanford University. SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY AID ECONOMIC GROUTS Nathan Rosenberg Professor of Economics Stanford University This paper has been prepared for presentation at the 1987 Annual meeting of the AAAS, Chicago, 14 February 1987. My primary concern in this paper will be with certain aspects of the so- called high technology industries that are, I believe, highly relevant to America's economic growth prospects. The most direct way in which these aspects are relevant to economic growth is that they directly affect the country's ability to maintain or to improve its competitiveness in world markets. The term "science" appears in the title of this paper because the high technology industries with which I will be primarily concerned are, by common definition, those in which scientific inputs loom large - whether these inputs are measured in terms of the number of scientifically trained personnel or expenditures upon research and development (R&D). -

Education, and Retirement Saving B

Living with Defined Contribution Pensions Remaking Responsibility for Retirement Edited by Olivia S. Mitchell and Sylvester J. Schieber Published by The Pension Research Council The Wharton School ofthe University of Pennsylvania and University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia Copyright © 1998 The Pension Research Council ofthe Wharton School of the University ofPennsylvania All rights reserved Printed in the United States ofAmerica on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 Published by University ofPennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4011 Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Living with defined contribution pensions: remaking responsibility for retirement / edited by Olivia S. Mitchell and SylvesterJ. Schieber. p. em. "Pension Research Council publications." Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8122-3439-1 (cloth: alk. paper) I. Defined contribution plans - United States. 2. Old age pensions- United States-Finance. 3. Pension trusts- United States Finance. I. Mitchell, Olivia S. II. Schieber, SylvesterJ. HD7105.45.U6L58 1998 331.25'2'0973-dc21 98-13584 CIP Chapter 3 Financial Illiteracy, Education, and Retirement Saving B. Douglas Bernheim Most Americans save too little to maintain their standards of living after retirement. In the past, the typical worker has reached retirement with total savings insufficient to sustain his or her preretirement living stan dards (Diamond 1977; Hammermesh 1984).1 Since social security bene fits provide rather modest earnings replacement, and since defined -

MPA-849 Behavioral Public Finance

Queen’s School of Policy Studies, winter 2019 MPA-849 Behavioral Public Finance Faculty Contact Info: Weili DING, Sutherland Hall 321, Email: [email protected]. Course Description: Traditional public finance provides a simple but powerful framework to analyze the questions discussed on the front page of the newspaper every day. This framework, however, is often criticized for relying on an overly simple model of human behavior. Behavior economics advocates a psychologically richer perspective on human behavior for economic analysis. The course introduces this new development in public finance that not only attempts to apply psychology to public finance problems but also tries to reshape core public finance concepts such as moral hazard, deadweight loss and tax incidence. Who Should Take This Course: Students who are interested in public finance issues but not entirely satisfied with traditional analysis on government intervention, market failure and social welfare; Students who are interested in behavior economics and its applications; Students who want to learn new development in public finance. Course Prerequisites: Introductory Economics is required (MPA804 equivalent) and basic statistics is preferred (MPA805 equivalent). A previous course in public economics is also preferred (or MPA815 simultaneously). Required Readings: Assigned readings are integral parts of this course. They are essential to both your understanding of and success in the course. It is absolutely necessary that you complete the corresponding required readings before the class for which they are intended. Most of the readings are listed with links at the course website that will be available onQ. Reference Textbooks provide a structured background to the topics and terminologies the papers on the reading list relate to: I. -

Put Your Money Where Your Butt Is: a Commitment Contract for Smoking Cessation

Dartmouth College Dartmouth Digital Commons Dartmouth Scholarship Faculty Work 10-2010 Put Your Money Where Your Butt Is: A Commitment Contract for Smoking Cessation Xavier Giné The World Bank Dean Karlan Yale University Jonathan Zinman Dartmouth College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/facoa Part of the Behavioral Economics Commons, Health Economics Commons, and the Public Health Commons Dartmouth Digital Commons Citation Giné, Xavier; Karlan, Dean; and Zinman, Jonathan, "Put Your Money Where Your Butt Is: A Commitment Contract for Smoking Cessation" (2010). Dartmouth Scholarship. 2379. https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/facoa/2379 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Work at Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dartmouth Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2 October 2010 : 213–235 http://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi 10.1257/app.2.4.213( ) = Contents Put Your Money Where Your Butt Is: A Commitment Contract for Smoking Cessation† 213 Put Your Money Where Your Butt Is: I. CARES Product Design 217 II. Cue Cards Treatment Design 219 A Commitment Contract for Smoking Cessation† III. Experimental Design and Summary Statistics 219 IV. Results 223 A. CARES Take up 223 By Xavier Giné, Dean Karlan, and Jonathan Zinman* B. CARES Usage 223 C. Treatment Effects on Smoking Cessation 225 V. Conclusion 227 Appendix We designed and tested a voluntary commitment product to help Summaries of Three Open-Ended Follow-up Interviews 230 smokers quit smoking. -

Economics 102B Is Now Required for All Majors

rics, Economics 102B is now required for all majors. Students are encour- ECONOMICS aged to take Economics 102A and 102B before their senior year. The required number of field courses has increased from two to four. There Emeriti: (Professors) Theodore W. Anderson, Kenneth J. Arrow, Victor R. is now greater flexibility in the choice of electives, including upper-di- Fuchs, John G. Gurley, Donald Harris, Bert G. Hickman, James N. vision math and statistics. Rosse, Tibor Scitovsky, David A. Starrett Of the 75 units required for the major, at least 50 must be taken at Chair: Gavin Wright Stanford. Students cannot declare Economics as their major until they Professors: Takeshi Amemiya, Masahiko Aoki, B. Douglas Bernheim, have completed Economics 1 with a grade of ‘C+’ or better. Michael J. Boskin, Timothy F. Bresnahan, Paul A. David, Walter P. Students who declared Economics as their major prior to September Falcon, Lawrence Goulder, Avner Greif, Robert E. Hall, Peter J. 1, 1998, may opt to complete their Economics major under the old require- Hammond, Anne O. Krueger, Mordecai Kurz, Lawrence J. Lau, ments (see the 1997-98 Stanford Bulletin) or under the new requirements Thomas E. MaCurdy, Ronald I. McKinnon, Paul R. Milgrom, Roger listed below. G. Noll, John H. Pencavel, Nathan Rosenberg, Thomas J. Sargent, John B. Shoven, John B. Taylor, Frank Wolak, Gavin Wright REQUIREMENTS FOR THE ECONOMICS MAJOR (75 UNITS) Associate Professors: Susan Athey, Mark McClellan, Ilya Segal 1. Economics 1 (5 units): principles of economics. Assistant Professors: Patrick L. Bajari, Anjini Kochar, Dirk Krueger, 2. Economics 102A (5 units): introduction to statistical methods. -

Hayek's Divorce and Move to Chicago · Econ Journal Watch

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: https://journaltalk.net/articles/5973 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 15(3) September 2018: 301–321 Hayek’s Divorce and Move to Chicago Lanny Ebenstein1 LINK TO ABSTRACT The personal life of a great intellectual is not always highly pertinent. Al- though Friedrich Hayek may have been, in his son’s words, “the great philosopher with feet of clay” (L. Hayek 1994–1997), his clay feet would not necessarily detract from his scholarly contributions. But since Hayek was a moral philosopher—his title at the University of Chicago was Professor of Social and Moral Science—his personal life may be more relevant than would be the case for intellectuals in other fields. The history of Hayek’s personal life has not always, to this point, been accurately told. The story of his divorce and move to Chicago has often been presented as one in which he discovered after World War II on a visit to Vienna to see his mother and other family members that a distant cousin of his, Helene Bitterlich, with whom he had a relationship as a young man, felt free to marry him. After Helene’s husband died, she and Hayek decided to marry, requiring Hayek to divorce his first wife, the former Hella Fritsch. At the same time, it has been suggested, he began to feel out of place in England in the immediate postwar era as a result of the policies of the first Labour Party government. He relocated to America, having first sought a post in the Economics Department at the University of Chicago and then, after being turned down by it as a result of The Road to Serfdom (1944), having been offered a position in the Committee on Social Thought. -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Salamon, Peter; Komlos, John Working Paper The Poverty of Growth with Interdependent Utility Functions Munich Discussion Paper, No. 2005-9 Provided in Cooperation with: University of Munich, Department of Economics Suggested Citation: Salamon, Peter; Komlos, John (2005) : The Poverty of Growth with Interdependent Utility Functions, Munich Discussion Paper, No. 2005-9, Ludwig-Maximilians- Universität München, Volkswirtschaftliche Fakultät, München, http://dx.doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.619 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/104164 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Peter Salamon und John Komlos: The Poverty of Growth with Interdependent Utility Functions Munich Discussion Paper No. -

Policy and Choice: Public Finance Through the Lens of Behavioral

advance Praise For POLICY and CHOICE Mullai Congdon • Kling “Policy and Choice is a must-read for students of public finance. If you want to learn N William J. Congdon is a research director in Traditional public ἀnance provides a powerful how the emerging field of behavioral economics can help lead to better policy, there is atha the Brookings Institution’s Economic Studies framework for policy analysis, but it relies on a nothing better.” program, where he studies how best to apply model of human behavior that the new science , Harvard University, former chairman of the President’s Council of N. GreGory MaNkiw N behavioral economics to public policy. Economic Advisers, and author of Principles of Economics of behavioral economics increasingly calls into question. In Policy and Choice economists Jeἀrey R. Kling is the associate director for William Congdon, Jeffrey Kling, and Sendhil economic analysis at the Congressional Budget “This fantastic volume will become the standard reference for those interested in understanding the impact of behavioral economics on government tax and spending Mullainathan argue that public ἀnance not only Office, where he contributes to all aspects of the POLICY policies. The authors take a stream of research which had highlighted particular can incorporate many lessons of behavioral eco- agency’s analytic work. He is a former deputy ‘nudges’ and turn it into a comprehensive framework for thinking about policy in a nomics but also can serve as a solid foundation director of Economic Studies at Brookings. more realistic world where psychology is incorporated into economic decisionmaking. from which to apply insights from psychology Sendhil Mullainathan is a professor of This excellent book will be widely used and cited.” to questions of economic policy. -

WEAI Program 2010-FINAL.Pub

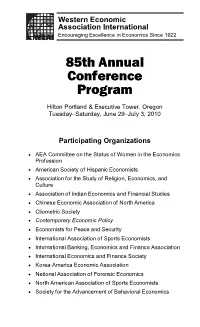

Western Economic Association International Encouraging Excellence in Economics Since 1922 85th Annual Conference Program Hilton Portland & Executive Tower, Oregon Tuesday–Saturday, June 29–July 3, 2010 Participating Organizations • AEA Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession • American Society of Hispanic Economists • Association for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Culture • Association of Indian Economics and Financial Studies • Chinese Economic Association of North America • Cliometric Society • Contemporary Economic Policy • Economists for Peace and Security • International Association of Sports Economists • International Banking, Economics and Finance Association • International Economics and Finance Society • Korea-America Economic Association • National Association of Forensic Economics • North American Association of Sports Economists • Society for the Advancement of Behavioral Economics START OR RENEW YOUR MEMBERSHIP TODAY! Western Economic Association International membership offers all of these great benefits... • Individual subscriptions to both • Reduced submission fee for your quarterly journals, Economic Inquiry individual paper submitted for and Contemporary Economic Policy presentation at either conference if (includes full collection online). you choose not to organize a • Reduced registration fees for the session. Annual Conference and for the • Manuscript submission fee is Biennial Pacific Rim Conference. waived for submitting your • Opportunity to organize your own conference paper to EI or CEP if sessions for both conferences with you do so within six months after the submission fees waived for all conference. included papers. • Reduced EI and CEP manuscript • Complimentary conference regis- submission fees for non- tration for either or both conference manuscripts. conferences if you are an • Discount on International Atlantic Institutional Member affiliate and Economic Society membership. organize a session. -

John Karl Scholz Address

John Karl Scholz Address: Office: Department of Economics University of Wisconsin–Madison Madison, Wisconsin 53711 1180 Observatory Drive Madison, Wisconsin 53706-1397 Phone: (608)262-5380 e-mail: [email protected] Education 1988, Ph.D., Economics, Stanford University. 1981, B.A., Economics and Mathematics, Carleton College Employment Nellie June Gray Professor of Economic Policy, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Department of Economics, since 2010 (Assistant Professor, Economics Department and La Follette Institute of Public Affairs, 1988-95; Associate Professor of Economics, 1995-98; and Professor of Economics since 1998) Deputy Assistant Secretary, Office of Tax Analysis, U.S. Treasury Department, January 1997- August 1998 Senior Staff Economist, Council of Economic Advisers, Executive Office of the President, Washington, D.C., September 1990-July 1991 Professional Appointments 2011 - today Coeditor, American Economic Journal – Economic Policy 2009 - 2011 Coeditor, Journal of Public Economics 2008 - today TIAA-CREF Institute Fellow 2008 - today Research Fellow, Netspar (Netherlands), Member of Netspar Scientific Counsel 2007 - 2009 Member, Internal Revenue Service Advisory Council (Tax Gap Committee) 2007 - 2009 Chair, NRC Panel on the Dynamics of Economic Well-Being System 2005 - 2008 Associate Editor, The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics 2005 International Monetary Fund Technical Assistance, South Korea 2004 Chair, National Research Council Panel on Enhancing the Data Infrastructure in Support of Food and Nutrition Programs, Research, and Decision Making 2003 - today Michigan Retirement Research Center Board of Outside Scholars 2003 - today Senior Research Affiliate at the Michigan National Poverty Center 2001 - 2003 Member, National Research Council Panel to Evaluate the USDA’s Methodology for Estimating Eligibility and Participation for the WIC Program 2001 - today Editorial Board, The B.E. -

The Role of Law in the New Institutional Economics

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 26 Law & The New Institutional Economics 2008 The Role of Law in the New Institutional Economics Rudolf Richter Stanford Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Law and Economics Commons Recommended Citation Rudolf Richter, The Role of Law in the New Institutional Economics, 26 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 13 (2008), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol26/iss1/3 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Role of Law in the New Institutional Economics Rudolf Richter∗ ABSTRACT To explain the role of law in the new institutional economics (NIE), we compare this approach with the economic analysis of law (EAL) of the 1970s when the NIE evolved. At that time the EAL was dominated by the “Chicago” or “market-based” approach that builds on the theory of perfect competition. Contracts are complete and Pareto efficient (allocative efficient). Ten years on, this approach was extended by informational economic models that are briefly touched upon here. After a few methodological considerations, the Article concentrates on the Williamsonian branch of NIE, i.e., the transaction cost approach (TCA). This theory argues that, in the real world of positive transaction costs, incomplete contracts can, at most, be efficient in a boundedly rational sense (“NIE-efficient”).