Katarina Bonnevier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Diss Reformatted II

“NEWS THAT STAYS NEWS”: TRANSFORMATIONS OF LITERATURE, GOSSIP, AND COMMUNITY IN MODERNITY Lindsay Rebecca Starck A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Gregory Flaxman Erin Carlston Eric Downing Andrew Perrin Pamela Cooper © 2016 Lindsay Rebecca Starck ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Lindsay Rebecca Starck: “News that stays news”: Transformations of Literature, Gossip, and Community in Modernity (Under the direction of Gregory Flaxman and Erin Carlston) Recent decades have demonstrated a renewed interest in gossip research from scholars in psychology, sociology, and anthropology who argue that gossip—despite its popular reputation as trivial, superficial “women’s talk”—actually serves crucial social and political functions such as establishing codes of conduct and managing reputations. My dissertation draws from and builds upon this contemporary interdisciplinary scholarship by demonstrating how the modernists incorporated and transformed the popular gossip of mass culture into literature, imbuing it with a new power and purpose. The foundational assumption of my dissertation is that as the nature of community changed at the turn of the twentieth century, so too did gossip. Although usually considered to be a socially conservative force that serves to keep social outliers in line, I argue that modernist writers transformed gossip into a potent, revolutionary tool with which modern individuals could advance and promote the progressive ideologies of social, political, and artistic movements. Ultimately, the gossip of key American expatriates (Henry James, Djuna Barnes, Janet Flanner, and Ezra Pound) became a mode of exchanging and redefining creative and critical values for the artists and critics who would follow them. -

Surviving Set Theory: a Pedagogical Game and Cooperative Learning Approach to Undergraduate Post-Tonal Music Theory

Surviving Set Theory: A Pedagogical Game and Cooperative Learning Approach to Undergraduate Post-Tonal Music Theory DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Angela N. Ripley, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: David Clampitt, Advisor Anna Gawboy Johanna Devaney Copyright by Angela N. Ripley 2015 Abstract Undergraduate music students often experience a high learning curve when they first encounter pitch-class set theory, an analytical system very different from those they have studied previously. Students sometimes find the abstractions of integer notation and the mathematical orientation of set theory foreign or even frightening (Kleppinger 2010), and the dissonance of the atonal repertoire studied often engenders their resistance (Root 2010). Pedagogical games can help mitigate student resistance and trepidation. Table games like Bingo (Gillespie 2000) and Poker (Gingerich 1991) have been adapted to suit college-level classes in music theory. Familiar television shows provide another source of pedagogical games; for example, Berry (2008; 2015) adapts the show Survivor to frame a unit on theory fundamentals. However, none of these pedagogical games engage pitch- class set theory during a multi-week unit of study. In my dissertation, I adapt the show Survivor to frame a four-week unit on pitch- class set theory (introducing topics ranging from pitch-class sets to twelve-tone rows) during a sophomore-level theory course. As on the show, students of different achievement levels work together in small groups, or “tribes,” to complete worksheets called “challenges”; however, in an important modification to the structure of the show, no students are voted out of their tribes. -

Resistance Through 'Robber Talk'

Emily Zobel Marshall Leeds Beckett University [email protected] Resistance through ‘Robber Talk’: Storytelling Strategies and the Carnival Trickster The Midnight Robber is a quintessential Trinidadian carnival ‘badman.’ Dressed in a black sombrero adorned with skulls and coffin-shaped shoes, his long, eloquent speeches descend from the West African ‘griot’ (storyteller) tradition and detail the vengeance he will wreak on his oppressors. He exemplifies many of the practices that are central to Caribbean carnival culture - resistance to officialdom, linguistic innovation and the disruptive nature of play, parody and humour. Elements of the Midnight Robber’s dress and speech are directly descended from West African dress and oral traditions (Warner-Lewis, 1991, p.83). Like other tricksters of West African origin in the Americas, Anansi and Brer Rabbit, the Midnight Robber relies on his verbal agility to thwart officialdom and triumph over his adversaries. He is, as Rodger Abrahams identified, a Caribbean ‘Man of Words’, and deeply imbedded in Caribbean speech-making traditions (Abrahams, 1983). This article will examine the cultural trajectory of the Midnight Robber and then go on to explore his journey from oral to literary form in the twenty-first century, demonstrating how Jamaican author Nalo Hopkinson and Trinidadian Keith Jardim have drawn from his revolutionary energy to challenge authoritarian power through linguistic and literary skill. The parallels between the Midnight Robber and trickster figures Anansi and Brer Rabbit are numerous. Anansi is symbolic of the malleability and ambiguity of language and the roots of the tales can be traced back to the Asante of Ghana (Marshall, 2012). -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY An Jingfu (1994) The Pain of a Half Taoist: Taoist Principles, Chinese Landscape Painting, and King of the Children . In Linda C. Ehrlich and David Desser (eds.). Cinematic Landscapes: Observations on the Visual Arts and Cinema of China and Japan . Austin: University of Texas Press, 117–25. Anderson, Marston (1990) The Limits of Realism: Chinese Fiction in the Revolutionary Period . Berkeley: University of California Press. Anon (1937) “Yueyu pian zhengming yundong” [“Jyutpin zingming wandung” or Cantonese fi lm rectifi cation movement]. Lingxing [ Ling Sing ] 7, no. 15 (June 27, 1937): no page. Appelo, Tim (2014) ‘Wong Kar Wai Says His 108-Minute “The Grandmaster” Is Not “A Watered-Down Version”’, The Hollywood Reporter (6 January), http:// www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/wong-kar-wai-says-his-668633 . Aristotle (1996) Poetics , trans. Malcolm Heath (London: Penguin Books). Arroyo, José (2000) Introduction by José Arroyo (ed.) Action/Spectacle: A Sight and Sound Reader (London: BFI Publishing), vii-xv. Astruc, Alexandre (2009) ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Caméra-Stylo ’ in Peter Graham with Ginette Vincendeau (eds.) The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks (London: BFI and Palgrave Macmillan), 31–7. Bao, Weihong (2015) Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915–1945 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press). Barthes, Roland (1968a) Elements of Semiology (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1968b) Writing Degree Zero (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1972) Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers), New York: Hill and Wang. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 203 G. -

Pierrot Lunaire Translation

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) Pierrot Lunaire, Op.21 (1912) Poems in French by Albert Giraud (1860–1929) German text by Otto Erich Hartleben (1864-1905) English translation of the French by Brian Cohen Mondestrunken Ivresse de Lune Moondrunk Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt, Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux The wine we drink with our eyes Gießt Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder, A flots verts de la Lune coule, Flows nightly from the Moon in torrents, Und eine Springflut überschwemmt Et submerge comme une houle And as the tide overflows Den stillen Horizont. Les horizons silencieux. The quiet distant land. Gelüste schauerlich und süß, De doux conseils pernicieux In sweet and terrible words Durchschwimmen ohne Zahl die Fluten! Dans le philtre yagent en foule: This potent liquor floods: Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt, Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux The wine we drink with our eyes Gießt Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder. A flots verts de la Lune coule. Flows from the moon in raw torrents. Der Dichter, den die Andacht treibt, Le Poète religieux The poet, ecstatic, Berauscht sich an dem heilgen Tranke, De l'étrange absinthe se soûle, Reeling from this strange drink, Gen Himmel wendet er verzückt Aspirant, - jusqu'à ce qu'il roule, Lifts up his entranced, Das Haupt und taumelnd saugt und schlürit er Le geste fou, la tête aux cieux,— Head to the sky, and drains,— Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt. Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux! The wine we drink with our eyes! Columbine A Colombine Colombine Des Mondlichts bleiche Bluten, Les fleurs -

Museums in Stockholm

Museums in Stockholm PHOTO: OLA ERICSON FOR THE LATEST UPDATES ON STOCKHOLM, VISIT THE OFFICIAL WEBSITE VISITSTOCKHOLM.COM Museums in Stockholm BERGIANSKA TRÄDGÅRDEN BERGIUS BOTANIC GARDEN Discover Stockholm´s museums with their world-class collections, pioneering exhibitions and extraordinary historical objects. Botanical garden beautifully situated at Lake Brunnsviken. A paradise for plant enthusiasts with thousands of trees, shrubs and herbs from around the world. Exotic, heat-loving plants thrive in the Victoria House and Edvard Anderson Conservatory. AQUARIA VATTENMUSEUM Café, shop and restaurant. AQUARIA WATER MUSEUM Opening hours: The Park daily. Edvard Anderson Conservatory: Oct-Mar Mon- Fri 11am- 4pm, Sat- Sun Falkenbergsgatan 2. Djurgården 11am-5pm Apr-Sep daily 11am- 5pm. www.aquaria.se The Victoria House: May-Sep Mon- Fri 11am- 4pm, Sat-Sun 11am-5pm. ARKITEKTURMUSEUM Metro station: Universitetet, Bus:40 MUSEUM OF ARCHITECTURE Bergianska trädgården All you need to know about Swedish architecture and construction from +46 (0) 8 545 91 700 the 19th century until today. Exhibitions featuring drawings, models, design www.bergianska.se and examples of sustainable urban development. Take a tour and participate in creative activities for children on Sundays. Library, BIOLOGISKA MUSEET collections, book store and café. BIOLOGICAL MUSEUM Opening hours: Tues 10am- 8pm, Wed-Sun Lejonslätten, Djurgården 10am-6pm. www.biologiskamuseet.com Metro station: Kungsträdgården Bus: 2, 55, 62, 65, 76 Skeppsholmen BONNIERS KONSTHALL +46 (0) 8 587 270 00 BONNIERS CONTEMPORARY ART www.arkitekturmuseet.se Torsgatan 19. Norrmalm ARMÉMUSEUM www.bonnierskonsthall.se ARMY MUSEUM CARL ELDHS ATELJÉMUSEUM Riddargatan 13. Östermalm CARL ELDH’S STUDIO MUSEUM www.armemuseum.se Lögebodavägen 10. -

A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Alfred University Clowning

A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Alfred University Clowning as an Act of Social Critique, Subversive and Cathartic Laughter, and Compassion in the Modern Age by Danny Gray In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Alfred University Honors Program May 9th, 2016 Under the Supervision of: Chair: Stephen Crosby Committee Members: M. Nazim Kourgli David Terry “Behind clowns, sources of empathy, masters of the absurd, of humor, they who draw me into an inexplicable space-time capsule, who make my tears flow for no reason. Behind clowns, I am surprised to sense over and over again humble people, insignificant we might even say, stubbornly incapable of explaining, outside the ring, the unique magic of their art.” - Leandre Ribera “The genius of clowning is transforming the little, everyday annoyances, not only overcoming, but actually transforming them into something strange and terrific. It is the power to extract mirth for millions out of nothing and less than nothing.” - Grock 1 Contents Introduction 3 I: Defining Clown 5 II: Clowning as a Social Institution 13 III: The Development of Clown in Western Culture 21 IV: Clowns in the New Millennium 30 Conclusion 39 References 41 2 The black and white fuzz billowed across the screen as my grandmother popped in a VHS tape: Saltimbanco, a long-running Cirque du Soleil show recorded in the mid-90’s. I think she wanted to distract me for an hour while she worked on a pot of gumbo, rather than stimulate an interest in circus life. Regardless, I was well and truly engrossed in the program. -

Narrative Structure and Purpose in Arnold Schoenberg's Pierrot

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Clown: Narrative Structure and Purpose in Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire Mike Fabio Introduction In September of 1912, a 37-year-old Arnold Schoenberg sat in a Berlin concert hall awaiting the premier of his 21st opus, Pierrot Lunaire. A frail man, as rash in his temperament as he was docile when listening to his music, Schoenberg watched as the lights dimmed and a fully costumed Pierrot took to the stage, a spotlight illuminating him against a semitransparent black screen through which a small instrumental ensemble could be seen. But as Pierrot began singing, the audience quickly grew uneasy, noting that Pierrot was in fact a woman singing in the most awkward of styles against a backdrop of pointillist atonal brilliance. Certainly this was not Beethoven. In a review of the concert, music critic James Huneker wrote: The very ecstasy of the hideous!…Schoenberg is…the cruelest of all composers, for he mingles with his music sharp daggers at white heat, with which he pares away tiny slices of his victim’s flesh. Anon he twists the knife in the fresh wound and you receive another thrill…. There is no melodic or harmonic line, only a series of points, dots, dashes or phrases that sob and scream, despair, explode, exalt and blaspheme.1 Schoenberg was no stranger to criticism of this nature. He had grown increasingly contemptuous of critics, many of whom dismissed his music outright, even in his early years. When Schoenberg entered his atonal period after 1908, the criticism became far more outrageous, and audiences were noted to have rioted and left the theater in the middle of pieces. -

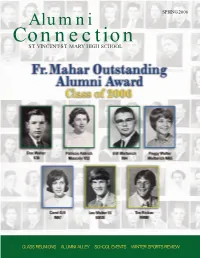

Alumni Connection Winter

Alumni SPRING 2006 Connection ST. VINCENT-ST. MARY HIGH SCHOOL CLASS REUNIONS ALUMNI ALLEY SCHOOL EVENTS WINTER SPORTS REVIEW IT’S HAPPENING HERE 5 IN THIS ISSUE MEMORIAL MASS: The Miller Family 3 WALL OF VISION The Wall of Vision is a tribute to the lead donors in the Share the Vision capital campaign. 18 MAHAR OUTSTANDING ALUMNI AWARD 2006 This award honors living graduates of St. Vincent, St. Mary and St. Vincent- St. Mary high schools. There are six recipients this year. 22 THROUGH THESE DOORS... Read about the wonderful work our faculty and staff is doing. 6 1FIRST WORD ALUMNI ALLEY: Jane McCormish Sparhawk V39 is a photogra- pher. Pictured above is an example of her work. Read more about Jane and other alumni in Alumni Alley. Russian Mural 8 IN CELEBRATION OF THEIR ADMIRATION OF THE RUSSIAN CULTURE and as a CLASS REUNIONS: V70 classmates (L-R) Sue Gerbasi lasting momento for years to come, student volunteers from Russian Bartlebaugh, Betty Delagrange Schnitzler, Mary Ellen Phillips Club painted a colorful mural. This mural is on a wall in the room shared MacDonald and Mike Metzler by Mr. Neary, Drama and Mr. O’Neil, Russian Language. The design is an impressionistic representation of St. Basil’s Cathedral. The idea, for- mulated by senior Mamie Williamson, came from a design on a T-shirt bought in Russia. The design was copied onto a transparency using a scanner and then projected onto the wall where it was outlined in chalk and painted. Also helping with the mural were two graduates and for- mer Russian students, Brett Wenneman and Betsy Mason. -

Programme for Sweden Live: National Day @ Home

Programme for Sweden live: National Day @ home 8:00 CET Coming up this hour: • The Cantores Sofiae choir sings ‘En vänlig grönska’ • A greeting from the Prime Minister of Sweden Stefan Löfven • At home with Issam Alghaeb and Brita Björs • Cooking with chef Camilla Hamid • At home with Oscar Höglund and Alexandra Pascalidou • Guided tour of the Royal Armory (Livrustkammaren) • A National Day Greeting from Her Royal Highness The Crown Princess and Her Family • Musical performance by Jens Lekman • A view of Holmön 9:00 CET Coming up this hour: • At home with Mouna Esmaeilzadeh and Fredrik Heintz • A monologue in Sami from Giron Sámi Téahter in Kiruna • At home with Jan Eliasson • Swedish Radio’s P2 choir sings ‘Uti vår hage’ • Let’s fika with Maral Moghadasi • Guided tour of the Royal Armory (Livrustkammaren) • Musical performance by Oscar Zia • At home with Johanna Sandahl and Abdulla Miri • Cooking with chef Jessica Frej • Musical greeting by Anne Sofie von Otter • At home with Jonathan Rollins, Basshunter and Amanda Lundeteg • A guided tour of the Vasa Museum • A National Day Greeting from Her Royal Highness The Crown Princess and Her Family • Sweden’s National Anthem performed by Nils Landgren • At home with Fred Taikon and HBTQUL • A view of Gävle 10:00 CET Coming up this hour: • Musical Performance by Jay-Jay Johanson • Let’s fika with Shaima Alraee • At home with Johan Wille Burnett and Bea Åkerlund • Musical performance by ionnalee • A greeting from the Prime Minister of Sweden Stefan Löfven • Cooking with chef Gustav Johansson • -

Behind the Scenes of the City: the Hidden, the Forbidden, the Forgotten November 18–19, 2020 Stockholm City Museum

Behind the Scenes of the City: The Hidden, the Forbidden, the Forgotten November 18–19, 2020 Stockholm City Museum Wednesday November 18 11.00–13.00 Conference registration and lunch Stockholm City Museum, auditorium, 2nd floor. Light lunch and coffee will be served during registration. 13.00–13.10 Welcome and introduction Fredrik Linder, Director, Stockholm City Museum, Rebecka Lennartsson, Associate Professor, Stockholm City museum, and Karin Carlsson, PhD, Department of History, Stockholm University. 13.10–13.50 Keynote speaker: Beatriz Colomina Howard Crosby Butler Professor of the History of Architecture, School of architecture, Princeton university, USA. 14.00–15.00 Parallel sessions I. Thresholds, Borders and Spaces in Between Chair: Heiko Droste, Professor, Head of Institute of Urban History, Stockholm University. How to Make Differences: Entrances and the Role of the Doorman in Residential Buildings During the Turn of the 20th Century Karin Carlsson, PhD, Department of History, Stockholm university. Dad on Display: Commercial Construction of Gender and the Modern Man in the 1930s Shop Windows Orsi Husz, Senior Lecturer, Associate Professor and Researcher at Department of History, Uppsala University and Klara Arnberg, Associate Professor and Researcher at the Department of Economic History and International Relations, Stockholm University. II. Spaces and Places in Transformation Chair: Thomas Wimark, Senior Lecturer and Associate Professor, Department of Social and Economic Geography, Uppsala University. Hidden Projections: Cinematic Resistance From the Urban Interiors of Australia Martin Abbott and Jennifer Minner, Associate Professor, City and Regional Planning, Cornell University, USA. Impact of the Botkyrka Project on Gender Equality and Youth Participation: A Capability Approach Perspective on #UrbanGirlsMovement Vittorio Esposito, Master student, Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm. -

Connecting Collecting 30 Years of Samdok LEADER

S A M D O K • S V E N S K A K U L T U R H I S T O R I S K A M U S E E R I S A M A R B E T E SAMTID &museer No 2 2007. Volume 31. Connecting Collecting 30 years of Samdok LEADER & No 2, November 2007. Volume 31. Contents Towards extended Towards extended collaboration 2 Christina Mattsson collaboration A network for developing collecting and research 3 Eva Fägerborg By Christina Mattsson Reflecting collecting 4 Thirty years ago, the Swedish It is we museum employees who pass Eva Silvén » museums of cultural history judgement on what is to be remem- Updating Sweden – contemporary created the cooperative organization bered and what is to be forgotten, what perspectives on cultural encounters 6 Samdok to steer attention away from future generations should see. No other Leif Magnusson the old peasant society towards the rap- institutions take the responsibility for What’s it like at home? 8 idly changing industrial society. With preserving material culture. The muse- Mikael Eivergård and Johan Knutsson the aid of Samdok, the museums would ums’ collecting work is also significant Leisure as a mirror of society 10 describe the entire transition from self- for today’s people, by observing and Marie Nyberg and Christine Fredriksen sufficiency to the information society, participating in contemporary proc- Between preservation and change – the perhaps the most dramatic period in esses. built environment as a mirror of the times 12 the life of individuals in Sweden – the Museums in different parts of the Barbro Mellander and Anna Ulfstrand time when people experienced more world have similar missions, and our Nature – an exploited heritage 14 changes in their living conditions than problems are in general the same.