On Heroes, Hero Worship, and the Heroic in History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William H. Hall High School

WILLIAM H. HALL HIGH SCHOOL WARRIORS Program of Studies 2016-2017 WILLIAM HALL HIGH SCHOOL 975 North Main Street West Hartford, Connecticut 06117 Phone: 860-232-4561 Fax: 860-236-0366 CENTRAL OFFICE ADMINISTRATION Mr. Thomas Moore – Superintendent Mr. Paul Vicinus - Assistant Superintendent Dr. Andrew Morrow – Assistant Superintendent BOARD OF EDUCATION Dr. Mark Overmyer-Velazquez – Chairperson Ms. Tammy Exum – Vice-Chair Ms Carol A Blanks – Secretary Dr. Cheryl Greenberg Mr. Dave Pauluk Mr. Jay Sarzen Mr. Mark Zydanowicz HALL HIGH SCHOOL ADMINISTRATION Mr. Dan Zittoun – Principal Mr. John Guidry - Assistant Principal Dr. Gretchen Nelson - Assistant Principal Ms. Shelley A. Solomon - Assistant Principal DEPARTMENT SUPERVISORS Mrs. Lucy Cartland – World Languages Mr. Brian Cohen – Career & Technical Education Lisa Daly – Physical Education and Health Mr. Chad Ellis – Social Studies Mr. Tor Fiske – School Counseling Mr. Andrew Mayo – Performing Arts Ms. Pamela Murphy – Visual Arts Dr. Kris Nystrom – English and Reading Mr. Michael Rollins – Science Mrs. Patricia Susla – Math SCHOOL COUNSELORS Mrs. Heather Alix Mr. Ryan Carlson Mrs. Jessica Evans Mrs. Amy Landers Mrs. Christine Mahler Mrs. Samantha Nebiolo Mr. John Suchocki Ms. Amanda Williams 1 Table of Contents Administration ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................................... -

Father Heinrich As Kindred Spirit

father heinrich as kindred spirit or, how the log-house composer of kentucky became the beethoven of america betty e. chmaj Thine eyes shall see the light of distant skies: Yet, COLE! thy heart shall bear to Europe's strand A living image of their own bright land Such as on thy glorious canvas lies. Lone lakes—savannahs where the bison roves— Rocks rich with summer garlands—solemn streams— Skies where the desert eagle wheels and screams— Spring bloom and autumn blaze of boundless groves. Fair scenes shall greet thee where thou goest—fair But different—everywhere the trace of men. Paths, homes, graves, ruins, from the lowest glen To where life shrinks from the fierce Alpine air, Gaze on them, till the tears shall dim thy sight, But keep that earlier, wilder image bright. —William Cullen Bryant, "To Cole, the Painter, Departing for Europe" (1829) More than any other single painting, Asher B. Durand's Kindred Spirits of 1849 has come to speak for mid-nineteenth-century America (Figure 1). FIGURE ONE (above): Asher B. Durand, Kindred Spirits (1849). The painter Thomas Cole and the poet William Cullen Bryant are shown worshipping wild American Nature together from a precipice high in the CatskiJI Mountains. Reprinted by permission of the New York Public Library. 0026-3079/83/2402-0035$0l .50/0 35 The work portrays three kinds of kinship: the American's kinship with Nature, the kinship of painting and poetry, and the kinship of both with "the wilder images" of specifically American landscapes. Commissioned by a patron at the time of Thomas Cole's death as a token of gratitude to William Cullen Bryant for his eulogy at Cole's funeral, the work shows Cole and Bryant admiring together the kind of images both had commem orated in their art. -

Gender, Ritual and Social Formation in West Papua

Gender, ritual Pouwer Jan and social formation Gender, ritual in West Papua and social formation A configurational analysis comparing Kamoro and Asmat Gender,in West Papua ritual and social Gender, ritual and social formation in West Papua in West ritual and social formation Gender, This study, based on a lifelong involvement with New Guinea, compares the formation in West Papua culture of the Kamoro (18,000 people) with that of their eastern neighbours, the Asmat (40,000), both living on the south coast of West Papua, Indonesia. The comparison, showing substantial differences as well as striking similarities, contributes to a deeper understanding of both cultures. Part I looks at Kamoro society and culture through the window of its ritual cycle, framed by gender. Part II widens the view, offering in a comparative fashion a more detailed analysis of the socio-political and cosmo-mythological setting of the Kamoro and the Asmat rituals. These are closely linked with their social formations: matrilineally oriented for the Kamoro, patrilineally for the Asmat. Next is a systematic comparison of the rituals. Kamoro culture revolves around cosmological connections, ritual and play, whereas the Asmat central focus is on warfare and headhunting. Because of this difference in cultural orientation, similar, even identical, ritual acts and myths differ in meaning. The comparison includes a cross-cultural, structural analysis of relevant myths. This publication is of interest to scholars and students in Oceanic studies and those drawn to the comparative study of cultures. Jan Pouwer (1924) started his career as a government anthropologist in West New Guinea in the 1950s and 1960s, with periods of intensive fieldwork, in particular among the Kamoro. -

Heroes (TV Series) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Pagina 1 Di 20

Heroes (TV series) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pagina 1 di 20 Heroes (TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Heroes was an American science fiction Heroes television drama series created by Tim Kring that appeared on NBC for four seasons from September 25, 2006 through February 8, 2010. The series tells the stories of ordinary people who discover superhuman abilities, and how these abilities take effect in the characters' lives. The The logo for the series featuring a solar eclipse series emulates the aesthetic style and storytelling Genre Serial drama of American comic books, using short, multi- Science fiction episode story arcs that build upon a larger, more encompassing arc. [1] The series is produced by Created by Tim Kring Tailwind Productions in association with Starring David Anders Universal Media Studios,[2] and was filmed Kristen Bell primarily in Los Angeles, California. [3] Santiago Cabrera Four complete seasons aired, ending on February Jack Coleman 8, 2010. The critically acclaimed first season had Tawny Cypress a run of 23 episodes and garnered an average of Dana Davis 14.3 million viewers in the United States, Noah Gray-Cabey receiving the highest rating for an NBC drama Greg Grunberg premiere in five years. [4] The second season of Robert Knepper Heroes attracted an average of 13.1 million Ali Larter viewers in the U.S., [5] and marked NBC's sole series among the top 20 ranked programs in total James Kyson Lee viewership for the 2007–2008 season. [6] Heroes Masi Oka has garnered a number of awards and Hayden Panettiere nominations, including Primetime Emmy awards, Adrian Pasdar Golden Globes, People's Choice Awards and Zachary Quinto [2] British Academy Television Awards. -

Oliver Cromwell and the Regicides

OLIVER CROMWELL AND THE REGICIDES By Dr Patrick Little The revengers’ tragedy known as the Restoration can be seen as a drama in four acts. The first, third and fourth acts were in the form of executions of those held responsible for the ‘regicide’ – the killing of King Charles I on 30 January 1649. Through October 1660 ten regicides were hanged, drawn and quartered, including Charles I’s prosecutor, John Cooke, republicans such as Thomas Scot, and religious radicals such as Thomas Harrison. In April 1662 three more regicides, recently kidnapped in the Low Countries, were also dragged to Tower Hill: John Okey, Miles Corbett and John Barkstead. And in June 1662 parliament finally got its way when the arch-republican (but not strictly a regicide, as he refused to be involved in the trial of the king) Sir Henry Vane the younger was also executed. In this paper I shall consider the careers of three of these regicides, one each from these three sets of executions: Thomas Harrison, John Okey and Sir Henry Vane. What united these men was not their political views – as we shall see, they differed greatly in that respect – but their close association with the concept of the ‘Good Old Cause’ and their close friendship with the most controversial regicide of them all: Oliver Cromwell. The Good Old Cause was a rallying cry rather than a political theory, embodying the idea that the civil wars and the revolution were in pursuit of religious and civil liberty, and that they had been sanctioned – and victory obtained – by God. -

England 1625-1660: Charles I, the Civil War and Cromwell Ebook, Epub

ENGLAND 1625-1660: CHARLES I, THE CIVIL WAR AND CROMWELL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dale Scarboro | 304 pages | 30 May 2005 | HODDER EDUCATION | 9780719577475 | English | London, United Kingdom England 1625-1660: Charles I, the Civil War and Cromwell PDF Book He declared that "healing and settling" were the "great end of your meeting". Far to the North, Bermuda's regiment of Militia and its coastal batteries prepared to resist an invasion that never came. Cromwell controversy continued into the 20th century. Negotiations were entered into with Charles but rather than treat with Parliament in good faith, he urged on the Scots to attack again for a Second Civil War in Cromwell led a Parliamentary invasion of Ireland from — Before he joined Parliament's forces, Cromwell's only military experience was in the trained bands, the local county militia. His tolerance of Protestant sects did not extend to Catholics; his measures against them in Ireland have been characterised by some as genocidal or near-genocidal, [7] and his record is strongly criticised in Ireland. In , one of the first ships commissioned to serve in the American Continental Navy during the American Revolutionary War was named Oliver Cromwell. See also: Oliver Cromwell's head. Ordinary people took advantage of the dislocation of civil society in the s to gain personal advantages. In June, however, a junior officer with a force of some men seized the king and carried him away to the army headquarters at Newmarket. A second Parliament was called later the same year, and became known as the Long Parliament. The English conflict left some 34, Parliamentarians and 50, Royalists dead, while at least , men and women died from war-related diseases, bringing the total death toll caused by the three civil wars in England to almost , Of all the English dominions, Virginia was the most resentful of Cromwell's rule, and Cavalier emigration there mushroomed during the Protectorate. -

Johnston of Warriston

F a m o u s Sc o t s S e r i e s Th e following Volum es are now ready M S ARLYLE H ECT O R . M C HERSO . T HO A C . By C A P N LL N R M Y O L H T SM E T O . A A A SA . By IP AN A N H U GH MI R E T H LE SK . LLE . By W. K I A H K ! T LOR INN Es. JO N NO . By A . AY R ERT U RNS G BR EL SET OUN. OB B . By A I L D O H GE E. T H E BA L A I ST S. By J N DDI RD MER N Pro fe sso H ER KLESS. RICH A CA O . By r SIR MES Y SI MPSON . EV E L T R E S M SO . JA . By B AN Y I P N M R P o fesso . G R E BLA I KIE. T HOMAS CH AL E S. By r r W A D N MES S ELL . E T H LE SK. JA BO W . By W K I A I M L E OL H T SME T O . T OB AS S O L T T . By IP AN A N U G . T O MON D . FLET CHER O F SA LT O N . By . W . R U P Sir GEOR E DO L S. T HE BLACKWOOD G O . By G UG A RM M LEOD OH ELL OO . -

Villains, Victims, and Heroes in Character Theory and Affect Control

Social Psychology Quarterly 00(0) 1–20 Villains, Victims, and Heroes Ó American Sociological Association 2018 DOI: 10.1177/0190272518781050 in Character Theory and journals.sagepub.com/home/spq Affect Control Theory Kelly Bergstrand1 and James M. Jasper2 Abstract We examine three basic tropes—villain, victim, and hero—that emerge in images, claims, and narratives. We compare recent research on characters with the predictions of an established tradition, affect control theory (ACT). Combined, the theories describe core traits of the vil- lain-victim-hero triad and predict audiences’ reactions. Character theory (CT) can help us understand the cultural roots of evaluation, potency, and activity profiles and the robustness of profile ratings. It also provides nuanced information regarding multiplicity in, and sub- types of, characters and how characters work together to define roles. Character types can be strategically deployed in political realms, potentially guiding strategies, goals, and group dynamics. ACT predictions hold up well, but CT suggests several paths for extension and elaboration. In many cases, cultural research and social psychology work on parallel tracks, with little cross-talk. They have much to learn from each other. Keywords affect control theory, character theory, heroes, victims, villains On October 9, 2012, 15-year-old Malala including one attack in December 2014 Yousafzai went to school, despite the Tali- that killed 132 schoolchildren and another ban’s intense campaign to stop female in January 2016 where 22 people were education in her region of Pakistan and gunned down at a university. Why did despite its death threats against her and Malala’s story touch Western audiences, her father. -

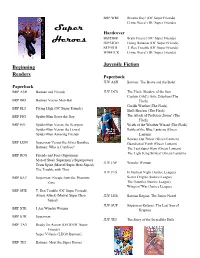

Super Heroes

BRP WRE Bizarro Day! (DC Super Friends) Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Super Hardcover B8555BR Brain Freeze! (DC Super Friends) Heroes H2934GO Going Bananas (DC Super Friends) S5395TR T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) W9441CR Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Juvenile Fiction Beginning Readers Paperback JUV ASH Batman: The Brave and the Bold Paperback BRP ASH Batman and Friends JUV DCS The Flash: Shadow of the Sun Captain Cold’s Artic Eruption (The BRP BRI Batman Versus Man-Bat Flash) Gorilla Warfare (The Flash) BRP ELI Flying High (DC Super Friends) Shell Shocker (The Flash) BRP FIG Spider-Man Saves the Day The Attack of Professor Zoom! (The Flash) BRP HIL Spider-Man Versus the Scorpion Wrath of the Weather Wizard (The Flash) Spider-Man Versus the Lizard Battle of the Blue Lanterns (Green Spider-Man Amazing Friends Lantern) Beware Our Power (Green Lantern) BRP LEM Superman Versus the Silver Banshee Guardian of Earth (Green Lantern) Batman: Who is Clayface? The Last Super Hero (Green Lantern) The Light King Strikes! (Green Lantern) BRP ROS Friends and Foes (Superman) Man of Steel: Superman’s Superpowers JUV JAF Wonder Woman Team Spirit (Marvel Super Hero Squad) The Trouble with Thor JUV JUS In Darkest Night (Justice League) BRP SAZ Superman: Escape from the Phantom Secret Origins (Justice League) Zone The Gauntlet (Justice League) Wings of War (Justice League) BRP SHE T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) Aliens Attack (Marvel Super Hero JUV LER Batman Begins: The Junior Novel Squad) JUV SUP Superman Returns: The Last Son of BRP STE I Am Wonder -

Cromwellian Anger Was the Passage in 1650 of Repressive Friends'

Cromwelliana The Journal of 2003 'l'ho Crom\\'.Oll Alloooluthm CROMWELLIANA 2003 l'rcoklcnt: Dl' llAlUW CO\l(IA1© l"hD, t'Rl-llmS 1 Editor Jane A. Mills Vice l'l'csidcnts: Right HM Mlchncl l1'oe>t1 l'C Profcssot·JONN MOlUUU.., Dl,llll, F.13A, FlU-IistS Consultant Peter Gaunt Professor lVAN ROOTS, MA, l~S.A, FlU~listS Professor AUSTIN WOOLll'YCH. MA, Dlitt, FBA CONTENTS Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA PAT BARNES AGM Lecture 2003. TREWIN COPPLESTON, FRGS By Dr Barry Coward 2 Right Hon FRANK DOBSON, MF Chairman: Dr PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS 350 Years On: Cromwell and the Long Parliament. Honorary Secretary: MICHAEL BYRD By Professor Blair Worden 16 5 Town Farm Close, Pinchbeck, near Spalding, Lincolnshire, PEl 1 3SG Learning the Ropes in 'His Own Fields': Cromwell's Early Sieges in the East Honorary Treasurer: DAVID SMITH Midlands. 3 Bowgrave Copse, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 2NL By Dr Peter Gaunt 27 THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt Hon Writings and Sources VI. Durham University: 'A Pious and laudable work'. By Jane A Mills · Isaac Foot and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan 40 statesman, and to encourage the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is neither political nor sectarian, its aims being The Revolutionary Navy, 1648-1654. essentially historical. The Association seeks to advance its aims in a variety of By Professor Bernard Capp 47 ways, which have included: 'Ancient and Familiar Neighbours': England and Holland on the eve of the a. -

9/11 Heroes Run GORUCK Division Rules and Requirements

9/11 Heroes Run GORUCK Division Rules and Requirements The GORUCK division of the Travis Manion Foundation 9/11 Heroes Run requires participants to carry a weighted rucksack or other type weighted backpack. We welcome ruckers of all levels to join us and earn a patch, but to compete for a top finisher medal in the GORUCK division, the rucksack must contain the prescribed additional weight based on body weight: ● For participants weighing 149 lbs or less, a 10-pound weight is required to qualify for the competitive GORUCK division. ● For those weighing 150 lbs or more, a 20-pound weight is required to qualify for the competitive GORUCK division. ● Weighted vests are NOT considered rucks and will NOT qualify for the competitive GORUCK division. ● LEOs and Firefighters in full turnout gear DO qualify for the competitive GORUCK division. ● We will weigh your ruck, but not your body! Your body weight is on the honor system. Packs will be weighed at each event prior to the start. Ruckers will receive a bracelet and a special mark on their running bib showing their ruck has met the standard for medal consideration. Packs must be compliant with the prescribed weight for the duration of the event. Ruck for fun! We enthusiastically welcome ruckers who do not carry the minimum weight requirement to participate in the 9/11 Heroes Run and earn their patch! These participants will skip the weigh-in before the event and will not qualify for medal consideration. Come on out and ruck your yoga block! All participants are required to supply their own packs and weights. -

San Fransokyo's Finest

San Fransokyo’s Finest Deluxe Flying Baymax Licensee: Bandai MSRP: $39.99 Retailers: Mass Available: Now Large and in-charge, this massive Baymax is ready to fly into battle using all his great weapons and features. Towering at 11” inches with a soaring 18-inch wingspan, the Deluxe Flying Baymax features 20 points of articulation, multiple lights, sounds and other fun features such as a launching rocket fist. Baymax comes with a 4.5” Hiro Hamada figure, which when attached to Baymax’s back unlocks additional flying sounds that vary depending on whether Baymax is flying up, or down. Armor-Up Baymax Licensee: Bandai MSRP: $19.99 Retailers: Mass Available: Now Transform Baymax from his 6” white nursebot form to an 8” crime-fighting hero with the Armor-Up Baymax. 20 body armor pieces construct a powered-up Baymax, growing two inches in height while preparing for battle in his red armored suit. GoGo Tamago and Honey Lemon 11” Dolls $16.95 each Retailers: Disney Store and DisneyStore.com Available: Now These fully poseable character dolls feature their accessories from the film, including GoGo Tomago’s spinning ''mag-lev discs'' and high-speed armor and Honey Lemon’s messenger bag. 10” Projection/SFX Baymax Licensee: Bandai MSRP: $29.99 Retailers: Mass Available: Now Smooth and fun to touch, the 10” vinyl Baymax has an incredible projector feature in his belly, allowing fans to view images and hear sounds from the film. Baymax Plush-Medium-15” $19.95 Retailers: Disney Store and DisneyStore.com Available: Now Cuddle up to soft stuffed Baymax for compassionate care and comfort throughout the daily adventure of life.