Petticoat Sailor to She Crossing: Adaptation in Process, a Writer's Reflection on Adapting a Feature Length Screenplay Into

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salafists Scuttle Bid to Appoint Elbaradei As PM

SUBSCRIPTION SUNDAY, JULY 7, 2013 SHAABAN 28, 1434 AH www.kuwaittimes.net US leaker Gunmen Runaway Bartoli routs Snowden’s kill 42 in train explodes, Lisicki to hopes rise on Nigeria levels center of win first asylum8 offers school attack8 Canada15 town Wimbledon20 title Salafists scuttle bid to Max 48º Min 35º appoint ElBaradei as PM High Tide 00:20 & 10:20 Low Tide Islamists mass again • Qaradawi: Egyptians should back Morsi 05:01& 18:37 40 PAGES NO: 15862 150 FILS CAIRO: Egyptian state television said the interim prime 418 hopefuls in minister had not yet been chosen, after named officials Jet crash-lands in US and state media earlier said Mohamed ElBaradei would race as oppn be appointed yesterday. The late-night report followed Egypt’s second biggest Islamist group, which had initially backed a military-led political roadmap to guide the boycotts polls country to new elections, opposing the nomination of liberal politician ElBaradei. The military ousted Islamist By B Izzak President Mohamed Morsi on Wednesday, and his Muslim Brotherhood movement has led protests in KUWAIT: Registration for the July 27 election closed which dozens of people have yesterday after 418 candidates filed nomination been killed. papers including only eight women as the opposi- The Tamarod movement, tion remained steadfast by almost completely boy- which engineered mass cotting the second polls in a row in protest against protests culminating in the the amendment of the electoral law. Withdrawal of overthrow of Morsi, had earlier candidacy will remain open until seven days before announced the appointment of the election day, or on July 19. -

Fotogramas.9.1 Maquetación 3

RMC Medicina en fotogramas/ Medicine in Film Stills JMM Enfermedades infecciosas: fiebre tifoidea Ficha técnica Título: Albert Nobbs. Título original: Albert Nobbs. Otros títulos: El secreto de Albert Nobbs (Argentina, Chile, Perú). La increíble historia de Albert Nobbs (Méjico). País: Reino Unido, Irlanda, Francia, Estados Unidos. Año: 2011. Director: Rodrigo García. Música: Brian Byrne. Fotografía: Michael McDonough. Montaje: Steven Weisberg. Guión: Glenn Close, John Banville, Gabriella Prekop sobre el argumento de István Szabó basado en el relato corto The Singular Life of Albert Nobbs de George Moore. Intérpretes: Glenn Close, Antonia Campbell-Hughes, Mia Wasikowska, Pauline Collins, Maria Doyle Kennedy, Mark Williams, James Greene, Serena Brabazon, Michael McElhatton, Dolores Mullally, Bonnie McCormack, Phyllida Law, Brendan Gleeson, Kenneth Collard, Judy Donovan, Janet McTeer,… Color: color. Duración: 113 minutos. Género: drama. Idioma original: inglés. Productoras: Chrysalis Films, Canal+, Irish Film Board, Mockingbird Pictures, Morrison Films, Parallel Film Productions, Trillian Productions, WestEnd Films. Sinopsis: Albert Nobbs (Glenn Close) es una mujer, hija bastarda de madre desconocida, que desde los 14 años asumió la condición de varón para poder trabajar de camarero, empleo en el que alcanzó un prestigio tanto en el Reino Unido como en Irlanda. Durante la trama lo hace en un hotel de Dublín en el que vive y en el que hay Acción: finales del siglo XIX (Dublín). un brote de fiebre tifoidea. Cartel español. Premios: tres nominaciones al Óscar, a la Mejor Actriz Principal (Glenn Close), Mejor Actriz Secundaria (Janet McTeer) y maquillaje (2012). Enlaces: Albert Nobbs (2011). Disponible en: http://www.imdb.com/title/ tt1602098 Brusch JL. Typhoid Fever. -

The Manor CONTINUED on PAGE 1

SEPTEMBER / OCTOBER 2013 PROGRAM THE MANOR CONTINUED ON PAGE 1 NEW WORLD Documentaries SPECIAL ED CANADIAN & INTERNATIONAL FEATURES TO THE WONDER SPECIAL EVENTS 40 YEARS ON: THE NARRATION OF CHILEAN RESISTANCE AND EXILE IN CINEMA WWW.WINNIPEGCINEMATHEQUE.COM NEW WORLD Documentaries THE MANOR CHARLES BRADLEY: SOUL OF AMERICA THE MANOR DIR. POULL BRIEN DIR. SHAWNEY COHEN 2012 | USA | 74 MIN 2013 | CANADA | 78 MIN SUN SEPT 1 - 7:00 PM WED SEPT 18 & THU SEPT 19 - 7:00 PM WED SEPT 4 & THU SEPT 5 - 7:00 PM SAT SEPT 21 - 7:00 PM Co-presented with the Winnipeg Folk Festival SUN SEPT 22 - 2:00 PM Charles Bradley: Soul of America follows the extraordinary journey of singer THU SEPT 26 - 7:00 PM Charles Bradley during the electrifying and transformative months leading up to the release of his debut album "No Time for Dreaming." Following his sold Opening night selection at Hot Docs, The Manor is a riveting portrait of a family out album release show, Charles' life changed completely. Championed by who run a strip club. The Cohens were a tight-knit, Jewish suburban family critics and fans alike, the album became one of the most incredible success – the very picture of a happy family. Roger, an Israeli immigrant and Brenda, stories of the year, landing on Rolling Stone’s Top 50 albums of 2011 and a homemaker, were in love and devoted to their two sons, Shawney and catapulting Charles to over 110 performances in 17 countries on 3 continents Sammy. When Shawney was six years old his father bought “The Manor,” over the next year alone, including last year's amazing performance at the a small-town strip club. -

February Issue.Indd

Joe Paterno’s living legacyy rememberedremembered 116A Legalization of Writing across the marijuana debated curriculum 1B-4B 6A The Students’ Newspaper of Neshaminy High School Volume 80 Issue 5 February 14, 2012 www.playwickian.com 2001 Old Lincoln Highway Langhorne, Pa. 19047 Neshaminy presents ‘Phantom’ By Shealyn Miles News Editor NEWS FLASH On Feb. 8 students stole the spotlight, taking the legendary “Phantom of the Opera” to the Neshaminy stage. From the performances right down to the incredible atmosphere, students proved they were FCS Receives Nutrition Grant worthy of such a diffi cult production. “A lot of work was put into this The Family and Consumer Science production, it was the most difficult Department’s Nutrition Program role I’ve ever had to play,” senior Grace received the Consumer Wellness Sweeney, who plays Carlotta said. Center’s Nutrition Grant of $2000 for Indeed, this particular play had been the third consecutive year. The grant is a step up in the level of emotion and currently being funded for the 2011-2012 outstanding vocals from the cast. Students school year from applicants all over the kept their professionalism throughout country. Neshaminy was selected once the entire performance, wowing even the again due to the thorough reporting in many original “Phantom” fans. previous years that contributed to the Perhaps it was the prestigious props on-line CWC Natural Newsletter. that were utilized. Some of which included the boat that actually moved Annual Food Drive Begins Christine and the Phantom across the stage, the mirror in which the Phantom Interact and Gym Night have teamed stole Christine away in, and who could up again this year with a food drive. -

Albert Nobbs Notes FINAL 10.8.11 ITA

3 NOMINATION GOLDEN GLOBE ® DISTRIBUZIONE VIDEA 5 CDE Via Livigno, 50-00188 Roma - Tel 06.331851 - Fax 06.33185255 - [email protected] UFFICIO STAMPA ORNATO COMUNICAZIONE Via Flaminia 954 - 00191 Roma - Tel. 06.3341017 - 06.33213374 - [email protected] www.albertnobbs.it www.facebook.com/videa www.youtube.com/videa Sinossi La pluripremiata attrice Glenn Close (Albert Nobbs) indossa i panni di una donna coinvolta in un insolito triangolo amoroso. Travestita da uomo per poter lavorare e sopravvivere nell’Irlanda del XIX secolo, più di trent’anni dopo si ritrova prigioniera della sua stessa finzione. Nel prestigioso cast internazionale, Mia Wasikowska (Helen), Aaron Johnson (Joe) e Brendan Gleeson (Dr. Holloran), oltre a Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Janet McTeer, Brenda Fricker e Pauline Collins. Rodrigo Garcia dirige il film basato su un racconto dell’autore irlandese George Moore, adattato da Glenn Close insieme a John Banville, vincitore del premio Man Booker, e a Gabriella Prekop. NOTE DI PRODUZIONE IL LEGAME DI GLENN CLOSE con il personaggio di Albert Nobbs risale a Quasi 30 anni fa, ai tempi in cui recitò – nel 1982 – nella rappresentazione teatrale di Simone Benmussa, ispirata al racconto breve Albert Nobbs, scritto dall’autore irlandese del XIX secolo, George Moore. “Credo che Albert sia un grande personaggio e la storia, in tutta la sua disarmante semplicità, è molto potente dal punto di vista emotivo”, dichiara Close, la cui apparizione in Quella produzione Off-Broadway le valse critiche eccellenti e un Obie Award. Nonostante i grandi successi che Close ha collezionato nel corso della sua brillante carriera, quel personaggio le è rimasto dentro. -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs Albert Nobbs, ALBERT NOBBS, RODRIGO GARCIA, Golden Globe Award, role, characters, film credits, John Banville, John Boorman, Julie Lynn, starring role, television, Simone Benmussa, Brendan Gleeson, Radha Mitchell, Harry Potter, Aaron Johnson, Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award, George Roy Hill, Kerry Washington, Margarethe Cammermeyer, Mia Wasikowska, Joe Layton, Directors' Fortnight, Neil Jordan, BBC comedy series, Florida Film Festival, European Film Academy, award nomination, Arlene Kelly, Sweet Emma Dear Bobe, Dublin Theatre Festival, television drama, Michael Cristofer, Franco Zeffirelli, Harvey Goldsmith, Winner Locarno Film Festival, Harold Prince, Irish actor, Fountain House, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Richard Pearce, Norma Desmond, Merchant Ivory, Stephen Frears, Jack Hofsiss, Stephen Herek, Royal National Theatre, Tony Awards, Richard Marquand, Fatal Attraction, Feature Film Commission, Christopher Walken, Barbet Schroeder, Joe, MAIN characters, National Association of Theatre Owners, Andrei Konchalovsky, International Mental Health Research Organization, Monica Rawling, Glenn Jordan, Rose Troche, Panthera Conservation Advisory Committee, Julian Morris, Danny Boyle, JOE Aaron Johnson, British independent film, Kristen Scott Thomas, Golden Globe nomination, Simon Wincer, Colin Farrell, RODRIGO GARCIA GABRIELLA PREKOP JOHN BANVILLE GLENN CLOSE, GLENN CLOSE, Bonnie Curtis, John Travolta, Golden Globe, Michael Vartan, John Lennon, Rhys Meyers, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, London Film Critics, -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs Chrysalis Films présente Albert Nobbs Un film de RODRIGO GARCIA Avec GLENN CLOSE MIA WASIKOWSKA AARON JOHNSON LE RÊVE EXTRAORDINAIRE JANET McTEER d’une vie ordinaire PAULINE COLLINS BRENDA FRICKER JONATHAN RHYS MEYERS et BRENDAN GLEESON Durée: 1 h 57 SORTIE LE 22 FÉVRIER 2012 Distribution Presse Chrysalis Films Moonfleet 18 rue Saint Marc Jérôme Jouneaux, Isabelle Duvoisin 75002 Paris & Mounia Wissinger Tél : 01 43 33 77 62 10 rue d’ Aumale -75009 Paris Fax : 01 47 88 91 24 www.chrysalis-films.com Tél : 01 53 20 01 20 L’HISTOIRE u XIXème siècle, dans l’Irlande en proie à de terribles difficultés économiques, une femme se fait passer pour un homme afin de pouvoir travailler. Pendant trente ans, elle trompe son entourage, employée dans un hôtel sous le nom d’Albert aNobbs, en tant que majordome. NOTES DE PRODUCTION lA reNCoNtre D’UNe ACtrICe et D’UN rÔle rX : « C’était le deuxième jour de tournage de Glenn ; elle est venue me voir et m’a tendu un scénario en disant : « Je dois absolument jouer ce personnage sur le grand écran avant Glenn Close entretient un lien particulier avec le personnage d’Albert Nobbs depuis de mourir. » presque trente ans : en 1982, elle l’a interprété au théâtre, dans la pièce écrite et mise en scène par Simone Benmussa, LA vIe sINGULIère d’ALbert Nobbs, d’après UN rÉAlIsAteUr PoUr UNe PASSIoN la nouvelle de l’auteur irlandais du XIXe siècle George Moore. sa prestation lui a valu un obie Award. depuis son premier voyage de repérages en 2001 jusqu’au début de la production du Au cours de sa carrière, Glenn Close a toujours gardé un attachement certain pour ce film en 2011, Glenn Close n’a cessé de retravailler et de peaufiner le scénario. -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs This could be called a “chamber film,” adapting the word from chamber music, which implies intimate music played in a salon setting and often melding several solo instruments into a seamless harmony. The modest but very touching “Albert Nobbs” definitely qualifies as a chamber film, with its intimacy of setting, its gentle tone, and its bevy of actors serving as the concordant instruments in a Victorian dance of stilled passions. Albert Nobbs (Glenn Close) is a middle-aged woman living a life-long lie: she works as a male waiter in the restaurant of the turn-of-the-century Morrison Hotel in Dublin, a life she has chosen because it suits her and constitutes civilized behavior. Her/his (thatʼs the last time Iʼll use that locution in the review) motivation is suggested only once and obliquely. It appears she was the victim of sexual abuse as a young woman and retreated thereafter into a protected, sexless condition. She has always lived alone, done her job without fault, strived not to stand out, and to cover up her true identity. Albert does have a dream, however. She desires to be her own boss and has hoarded her salary over 30 years to put money down on a “nice” tobacco shop. Hers has been, of necessity, a life of routines carefully crafted—until she encounters two very different women. One is the lovely hotel maid, Helen Dawes (Mia Wasikowska), who Albert feels needs rescuing after being treated badly by her lover, a handsome bounder named Joe Mackin (Aaron Johnson). Another is the burly Mr. -

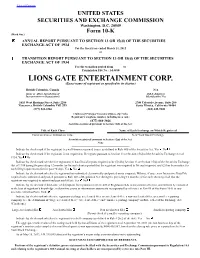

LIONS GATE ENTERTAINMENT CORP. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K (Mark One) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2012 or TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No.: 1-14880 LIONS GATE ENTERTAINMENT CORP. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) British Columbia, Canada N/A (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) 1055 West Hastings Street, Suite 2200 2700 Colorado Avenue, Suite 200 Vancouver, British Columbia V6E 2E9 Santa Monica, California 90404 (877) 848-3866 (310) 449-9200 (Address of Principal Executive Offices, Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (877) 848-3866 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Shares, without par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None ___________________________________________________________ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Yes No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Albert Nobbs April 15 & 16, 2012

ciné SARNIA presents Albert Nobbs April 15 & 16, 2012 A film fifteen years in the making, Albert and lost individual struggling to find hap- ALBERT Nobbs is the highly anticipated feature by piness amidst a bleak existence. With a acclaimed director Rodrigo Garc ía ( Mother supporting cast of characters that includes NOBBS and Child ). A Gala Presentation at the 2011 Mia Wasikowska ( Restless , Jane Eyre ), Janet Toronto International Film Festival ®, and McTeer ( Tideland ), Aaron Johnson Rodrigo García based on the stage play of the same name, (Nowhere Boy ), and Brendan Gleeson ( The Albert Nobbs is a moving and effectual por- Guard, In Bruges ), Albert Nobbs is certain to Cast : Glenn Close, Mia Wasikowska, trait of one woman’s struggle with personal be a hit among critics and audiences alike. Janet McTeer, Aaron Johnson, identity and self assurance in 19 th century Brendan Gleeson Ireland. “Critical acclaim and possible awards Run Time : 108 minutes Glenn Close ( “Damages ”, Evening) stars cosideration for Close’s touching, Country : United Kingdom/Ireland as the titular character, in what will arguably credible performance should generate Year : 2011 become one of the most celebrated perfor- an audience for this plaintive, old - Language : English mances of her career. Working as a butler in fashioned period drama.” a high-end hotel in Dublin, Nobbs lives an – Allan Hunter, Screen Daily intensely private and solitary life, closely guarding a secret. When a stranger is hired DISTRIBUTOR DETAILS on to paint the interior of the hotel, Nobbs Distributor : eOne Films finds herself forced to share a room with the Estimated Availability As Of : February overbearing gentleman, and the surprising 2012 truth quickly emerges. -

Fotogramas.9.1.Ing Maquetación 3

RMC Medicina en fotogramas/ Medicine in Film Stills JMM Infectious Diseases: Typhoid Fever Technical Details Original title: Albert Nobbs. Other titles: El secreto de Albert Nobbs (Argentina, Chile, Peru). La increíble historia de Albert Nobbs (Méjico). Country: UK, Ireland, France, USA. Year: 2011. Director: Rodrigo García. Music: Brian Byrne. Photography: Michael McDonough. Film editor: Steven Weisberg. Screenwriter: Glenn Close, John Banville, Gabriella Prekop about the István Szabó plot based on the short story The Singular Life of Albert Nobbs written by George Moore. Cast: Glenn Close, Antonia Campbell-Hughes, Mia Wasikowska, Pauline Collins, Maria Doyle Kennedy, Mark Williams, James Greene, Serena Brabazon, Michael McElhatton, Dolores Mullally, Bonnie McCormack, Phyllida Law, Brendan Gleeson, Kenneth Collard, Judy Donovan, Janet McTeer,… Color: Color. Rumtime: 113 minutes. Genre: Drama. Language: English. Productions Companies: Chrysalis Films, Canal+, Irish Film Board, Mockingbird Pictures, Morrison Films, Parallel Film Productions, Trillian Productions, WestEnd Films. Synopsis: Albert Nobbs (Glenn Close) is a woman, bas- tard daughter of unknown mother. Since she was fourteen she assumed the male condition in order to work as a waiter, an employment whith wich she achived a great reputation, both in the United Kingdom and Ireland. During the movie she is work- ing in a Dublin hotel, in wich she lives and where Action: Late nineteenth century (Dublin). there is a typhoid fever outbreak. American movie poster. Awards: Nominated for an Academy Award in the category of Best Actress, Best Supporting Actress and Best Makeup. Links: Albert Nobbs (2011). Avalaible from: http://www.imdb.com/title/ tt1602098 Brusch JL. Typhoid Fever. Avalaible from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/231135-overview García Sánchez JE, García Sánchez E. -

GENRE and CODE in the WORK of JOHN BANVILLE Kevin Boyle

GENRE AND CODE IN THE WORK OF JOHN BANVILLE Kevin Boyle St. Patrick’s College, Drumcondra Dublin City University School of Humanities Department of English Supervisor: Dr Derek Hand A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD April 2016 I hereby certify that this material, which T now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed:_____________________________ ID No.: 59267054_______ Date: Table of contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction: Genre and the Intertcxlual aspects of Banville's writing 5 The Problem of Genre 7 Genre Theory 12 Transgenerie Approach 15 Genre and Post-modernity' 17 Chapter One: The Benjamin Black Project: Writing a Writer 25 Embracing Genre Fiction 26 Deflecting Criticism from Oneself to One Self 29 Banville on Black 35 The Crossover Between Pseudonymous Authorial Sell'and Characters 38 The Opposition of Art and Craft 43 Change of Direction 45 Corpus and Continuity 47 Personae Therapy 51 Screen and Page 59 Benjamin Black and Ireland 62 Guilt and Satisfaction 71 Real Individuals in the Black Novels 75 Allusions and Genre Awareness 78 Knowledge and Detecting 82 Chapter Two: Doctor Copernicus, Historical Fiction and Post-modernity: