Community Well-Being and the Anishinabeg of the Lake Nipigon Region of Northern Ontario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimating Community Labour Market Indicators Between Censuses

Estimating Community Labour Market Indicators Between Censuses Report prepared by Dr. Bakhtiar Moazzami for The Local Employment Planning Council (LEPC) MARCH 9, 2017 Limitations: The North Superior Workforce Planning Board, your Local Employment Planning Council, recognizes the potential limitation of this document and will continue to seek out information in areas that require further analysis and action. The North Superior Workforce Planning assumes no responsibility to the user for the consequences of any errors or omissions. For further information, please contact: Madge Richardson Executive Director North Superior Workforce Planning Board Local Employment Planning Council 107B Johnson Ave. Thunder Bay, ON, P7B 2V9 [email protected] 807.346.2940 This project is funded in part by the Government of Canada and the Government of Ontario. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: INTRODUCTION AND THE OBJECTIVES OF THE PROJECT ................................................ 1 1.1 Objectives of the Present Project................................................................................................. 2 PART II: LABOUR MARKET INDICATORS ........................................................................................... 3 2.1. Defining Various Labour Market Indicators ............................................................................. 3 2.1.1. Labour Force Participation Rate ............................................................................................. 3 2.1.2. Employment-to-Population Ratio .......................................................................................... -

April 13, 2018 Ms. Kirsten Walli Board Secretary Ontario Energy Board

Lisa (Elisabeth) DeMarco Senior Partner 5 Hazelton Avenue, Suite 200 Toronto, ON M5R 2E1 TEL +1.647.991.1190 FAX +1.888.734.9459 [email protected] April 13, 2018 Ms. Kirsten Walli Board Secretary Ontario Energy Board P.O. Box 2319, 27th Floor 2300 Yonge Street Toronto, ON M4P 1E4 Dear Ms. Walli: Re: EB-2017-0049 Hydro One Networks Inc. application for electricity distriBution rates Beginning January 1, 2018 until DecemBer 31, 2022 We are counsel to Anwaatin Inc. (Anwaatin) in the above-mentioned proceeding. Please find enclosed the written evidence of Dr. Don Richardson, submitted on behalf of Anwaatin pursuant to Procedural Orders Nos. 3, 4, and 5. Yours very truly, Lisa (Elisabeth) DeMarco Jonathan McGillivray - 1 - ONTARIO ENERGY BOARD IN THE MATTER OF the Ontario Energy Board Act, 1998, S.O. 1998, c.15 (Schedule B) s. 78; AND IN THE MATTER OF an application by Hydro One Networks Inc. for electricity distribution rates beginning January 1, 2018, until December 31, 2022 (the Application). EB-2017-0049 EVIDENCE ANWAATIN INC. April 13, 2018 EB-2017-0049 Evidence of Anwaatin Inc. April 13, 2018 Page 2 of 16 EVIDENCE OF ANWAATIN INC. INTRODUCTION 1. My name is Dr. Don Richardson. I am the principal of Shared Value Solutions Ltd., a consultant to Anwaatin Inc. (Anwaatin). My curriculum vitae is attached at Appendix A. 2. I present this evidence to support Anwaatin and the Ontario Energy Board (the Board) in their consideration of the unique rights and concerns of Indigenous customers relating to distribution reliability, the Distribution System Plan (DSP), revenue requirement, and customer engagement being considered in the EB-2017-0049 proceeding (the Proceeding). -

The Opportunity - Grade 6-8 and Grade 2-5 Teaching Positions Available

Ojibway Nation of Saugeen General Delivery Savant Lake, Ontario P0V 2S0 Canada (807) 928 2824 Bus (807) 928 2710 Fax Ojibway Nation of Saugeen Job Posting The Opportunity - Grade 6-8 and grade 2-5 Teaching Positions available. Special Education experience would be an asset. The Ojibway Nation of Saugeen School is seeking reliable, self-motivated, hardworking individuals to fulfill the need of either a Regular Full Time and/or Term Contract Agreements* for Grade 6-8 and Grade 2-5 Teachers. Successful candidates will work under the supervision of the Principal and will perform teaching duties for a mixed age, low ratio classrooms. There is also opportunity for teachers with Special Education Teachers to apply. Preference will be given to applicants with this experience. The successful candidate would work with the Grade 6-8 students while also allocating time with special needs students in a supportive learning environment. The school’s student population is approximately 14. *Applicants who are interested are also encouraged to apply for short term contracts to finish the school year. The school year ends of June 2021. There would be opportunities to renew and negotiate contracts on a full-time basis at term end. Who We Are The School is located on the Ojibway Nation of Saugeen Community. The Nation operates a self-government and is responsible for the day to day operations of the Ojibway Nation of Saugeen. The school administers an elementary school for community students and offers a curriculum for students from JK to Grade 8. Where We Are Located The Ojibway Nation of Saugeen is an Ojibwa First Nation in the Canadian province of Ontario. -

Community Profiles for the Oneca Education And

FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 Political/Territorial Facts About This Community Phone Number First Nation and Address Nation and Region Organization or and Fax Number Affiliation (if any) • Census data from 2006 states Aamjiwnaang First that there are 706 residents. Nation • This is a Chippewa (Ojibwe) community located on the (Sarnia) (519) 336‐8410 Anishinabek Nation shores of the St. Clair River near SFNS Sarnia, Ontario. 978 Tashmoo Avenue (Fax) 336‐0382 • There are 253 private dwellings in this community. SARNIA, Ontario (Southwest Region) • The land base is 12.57 square kilometres. N7T 7H5 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 506 residents. Alderville First Nation • This community is located in South‐Central Ontario. It is 11696 Second Line (905) 352‐2011 Anishinabek Nation intersected by County Road 45, and is located on the south side P.O. Box 46 (Fax) 352‐3242 Ogemawahj of Rice Lake and is 30km north of Cobourg. ROSENEATH, Ontario (Southeast Region) • There are 237 private dwellings in this community. K0K 2X0 • The land base is 12.52 square kilometres. COPYRIGHT OF THE ONECA EDUCATION PARTNERSHIPS PROGRAM 1 FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 406 residents. • This Algonquin community Algonquins of called Pikwàkanagàn is situated Pikwakanagan First on the beautiful shores of the Nation (613) 625‐2800 Bonnechere River and Golden Anishinabek Nation Lake. It is located off of Highway P.O. Box 100 (Fax) 625‐1149 N/A 60 and is 1 1/2 hours west of Ottawa and 1 1/2 hours south of GOLDEN LAKE, Ontario Algonquin Park. -

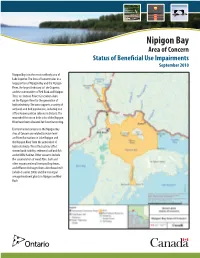

Nipigon Bay Area of Concern Status of Beneficial Use Impairments September 2010

Nipigon Bay Area of Concern Status of Beneficial Use Impairments September 2010 Nipigon Bay is in the most northerly area of Lake Superior. The Area of Concern takes in a large portion of Nipigon Bay and the Nipigon River, the largest tributary to Lake Superior, and the communities of Red Rock and Nipigon. There are Ontario Power Generation dams on the Nipigon River for the generation of hydroelectricity. The area supports a variety of wetlands and bird populations, including one of four known pelican colonies in Ontario. The watershed forests on both sides of the Nipigon River have been allocated for forest harvesting. Environmental concerns in the Nipigon Bay Area of Concern are related to water level and flow fluctuations in Lake Nipigon and the Nipigon River from the generation of hydroelectricity. These fluctuations affect stream bank stability, sediment load and fish and wildlife habitat. Other concerns include the accumulation of wood fibre, bark and other organic material from past log drives, and effluent discharges from a linerboard mill (which closed in 2006) and the municipal sewage treatment plants in Nipigon and Red Rock. PARTNERSHIPS IN ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Nipigon Bay was designated an Area of Concern in 1987 under the Canada–United States Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. Areas of Concern are sites on the Great Lakes system where environmental quality is significantly degraded and beneficial uses are impaired. Currently, there are 9 such designated areas on the Canadian side of the Great Lakes, 25 in the United States, and 5 that are shared by both countries. In each Area of Concern, government, community and industry partners are undertaking a coordinated effort to restore environmental quality and beneficial uses through a remedial action plan. -

Danahub 2021 – Reference Library E & O E Overview the Great Lakes Region Is the Living Hub of North America, Where It

Overview The Great Lakes region is the living hub of North America, where it supplies drinking water to tens of millions of people living on both sides of the Canada-US border. The five main lakes are: Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. Combined, the Great Lakes contain approximately 22% of the world’s fresh surface water supply. Geography and Stats The Great Lakes do not only comprise the five major lakes. Indeed, the region contains numerous rivers and an estimated 35,000 islands. The total surface area of the Great Lakes is 244,100 km2 – nearly the same size as the United Kingdom, and larger than the US states of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont and New Hampshire combined! The total volume of the Great Lakes is 6x1015 Gallons. This amount is enough to cover the 48 neighboring American States to a uniform depth of 9.5 feet (2.9 meters)! The largest and deepest of the Great Lakes is Lake Superior. Its volume is 12,100 Km3 and its maximum depth is 1,332 ft (406 m). Its elevation is 183 m above sea level. The smallest of the Great Lakes is Lake Erie, with a maximum depth of 64 m and a volume of 484 Km3. Lake Ontario has the lowest elevation of all the Great Lakes, standing at 74 m above sea level. The majestic Niagara Falls lie between Lakes Erie and Ontario, where there is almost 100 m difference in elevation. Other Rivers and Water Bodies The Great Lakes contain many smaller lakes such as Lake St. -

Community Strategic Plan 2011 - 2016

LAC DES MILLE LACS FIRST NATION THE COMMUNITY OF NEZAADIIKAANG The Place of Poplars COMMUNITY STRATEGIC PLAN 2011 - 2016 Prepared by Meyers Norris Penny LLP LAC DES MILLE LACS FIRST NATION THE COMMUNITY OF NEZAADIIKAANG COMMUNITY STRATEGIC PLAN Lac Des Mille Lacs First Nation Contact: Chief and Council c/o Quentin Snider, Band Manager Lac Des Mille Lacs First Nation Thunder Bay, ON P7B 4A3 MNP Contacts: Joseph Fregeau, Partner Kathryn Graham, Partner Meyers Norris Penny LLP MNP Consulting Services 315 Main Street South 2500 – 201 Portage Avenue Kenora, ON P9N 1T4 Winnipeg, MB R3B 3K6 807.468.1202 204.336.6243 [email protected] [email protected] LAC DES MILLE LACS FIRST NATION THE COMMUNITY OF NEZAADIIKAANG COMMUNITY STRATEGIC PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 2 Context for Community Strategic Planning ................................................................................................... 3 Past Plan ................................................................................................................................................... 3 The Process .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Membership -

Lake Ontario Lakewide Management Plan Status

LAKE ONTARIO LAKEWIDE MANAGEMENT PLAN STATUS APRIL 22, 2004 TAB L E O F CO NTEN TS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... ES-1 CHAPTER 1 STATE OF LAKE ONTARIO 1.1 Summary........................................................................................................................... 1-1 CHAPTER 2 BACKGROUND 2.1 Summary........................................................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Introduction to Lake Ontario............................................................................................... 2-1 2.2.1 Climate.................................................................................................................. 2-2 2.2.2 Physical Characteristics and Lake Processes ............................................................ 2-2 2.2.3 Aquatic Communities............................................................................................. 2-4 2.2.4 Demographics and Economy of the Basin................................................................ 2-6 2.3 LaMP Background.............................................................................................................. 2-8 2.4 LaMP Structure and Processes............................................................................................. 2-9 2.5 Actions and Progress..........................................................................................................2-10 2.6 -

Sander Vitreus) ⁎ Ursula Strandberga, , Satyendra P

Environment International 112 (2018) 251–260 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Environment International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envint Spatial and length-dependent variation of the risks and benefits of T consuming Walleye (Sander vitreus) ⁎ Ursula Strandberga, , Satyendra P. Bhavsarb, Tarn Preet Parmara, Michael T. Artsa a Ryerson University, Department of Chemistry and Biology, 350 Victoria St., Toronto, ON M5B 2K3, Canada b Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change, Sport Fish Contaminant Monitoring Program, Environmental Monitoring and Reporting Branch, 125 Resources Road, Toronto, ON M9P 3V6, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Handling Editor: Yong Guan Zhu Restricted fish consumption due to elevated contaminant levels may limit the intake of essential omega-3 fatty − − Keywords: acids, such as eicosapentaenoic (EPA; 20:5n 3) and docosahexaenoic (DHA; 22:6n 3) acids. We analyzed Risk-benefit lake- and length-specific mercury and EPA + DHA contents in Walleye (Sander vitreus; Mitchell 1818) from 20 Mercury waterbodies in Ontario, Canada, and used this information to calculate the theoretical intake of EPA + DHA Eicosapentaenoic acid when the consumption advisories are followed. The stringent consumption advisory resulted in decreased Docosahexaenoic acid EPA + DHA intake regardless of the EPA + DHA content in Walleye. Walleye length had a strong impact on the Sander vitreus EPA + DHA intake mainly because it was positively correlated with the mercury content and thereby con- Walleye sumption advisories. The highest EPA + DHA intake was achieved when smaller Walleye (30–40 cm) were consumed. The strong relationship between the consumption advisory and EPA + DHA intake enabled us to develop a more generic regression equation to estimate EPA + DHA intake from the consumption advisories, which we then applied to an additional 1322 waterbodies across Ontario, and 28 lakes from northern USA for which Walleye contaminant data are available but fatty acid data are missing. -

Rivers at Risk: the Status of Environmental Flows in Canada

Rivers at Risk: The Status of Environmental Flows in Canada Prepared by: Becky Swainson, MA Research Consultant Prepared for: WWF-Canada Freshwater Program Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of the river advocates and professionals from across Canada who lent their time and insights to this assessment. Also, special thanks to Brian Richter, Oliver Brandes, Tim Morris, David Schindler, Tom Le Quesne and Allan Locke for their thoughtful reviews. i Rivers at Risk Acronyms BC British Columbia CBM Coalbed methane CEMA Cumulative Effects Management Association COSEWIC Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada CRI Canadian Rivers Institute DFO Fisheries and Oceans Canada EBF Ecosystem base flow IBA Important Bird Area IFN Instream flow needs IJC International Joint Commission IPP Independent Power Producer GRCA Grand River Conservation Authority LWR Low Water Response MOE Ministry of Environment (Ontario) MNR Ministry of Natural Resources (Ontario) MRBB Mackenzie River Basin Board MW Megawatt NB New Brunswick NGO Non-governmental organization NWT Northwest Territories P2FC Phase 2 Framework Committee PTTW Permit to Take Water QC Quebec RAP Remedial Action Plan SSRB South Saskatchewan River Basin UNESCO United Nations Environmental, Scientific and Cultural Organization US United States WCO Water Conservation Objectives ii Rivers at Risk Contents Rivers at Risk: The Status of Environmental Flows in Canada CONTENTS Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... -

Final Report

Aboriginal Health Programs and Services Analysis & Strategies: Final Report SUBMITTED BY: DPRA CANADA 7501 KEELE ST. SUITE 300 CONCORD, ON L4K 1Y2 NW LHIN Aboriginal Health Programs and Services Analysis and Strategy Final Report April 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. IV ACRONYMS .............................................................................................................................................. VIII 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT .......................................................................................................... 1 2.0 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 LOCAL HEALTH INTEGRATION NETWORK ......................................................................................... 2 2.1.1 Brief Overview of the Local Health Integration Network.......................................................... 2 2.1.2 The North West Local Health Integration Network .................................................................. 3 2.2 NW LHIN POPULATION ................................................................................................................. -

November 2006

Volume 18 Issue 9 Published monthly by the Union of Ontario Indians - Anishinabek Nation Single Copy: $2.00 November 2006 Anishinabek policy to protect consumers GARDEN RIVER FN – Anishi- hope to develop our own economies nabek Nation citizens, regardless of ence to Anishinabek businesses nabek leaders have endorsed the as part of our long-range self-gov- place of residence. that provide good products and cus- development of a consumer policy ernment structures,” said Beaucage, “We don’t want any businesses tomer service, even if they have to designed to help keep more dollars who was empowered by Chiefs to take Anishinabek consumers for pay a modest premium.” in the pockets of citizens of their 42 at the Oct. 31-Nov. 1 Special Fall granted,” said Beaucage. “We are Beaucage will be appointing member First Nations. Assembly to oversee the develop- constantly hearing of situations a special working group which “About 70 cents of every dollar ment of an Anishinabek Consumer where our citizens are embarrassed will examine a broad range of is- coming into our communities are Policy and Bill of Rights. or harassed in retail establishments sues, including a possible certifi ca- being spent on off-reserve products The policy, to be completed in about their treaty rights to tax ex- tion process for businesses to earn and services,” said Grand Coun- time for the June, 2007 Anishinabek emption. If people want our busi- preferred supplier status, a bill of cil Chief John Beaucage. “What’s Grand Council Assembly, would ness, they will have to earn it