Secure Domain Name System (DNS) Deployment Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterizing Certain Dns Ddos Attacks

CHARACTERIZING CERTAIN DNS DDOSATTACKS APREPRINT Renée Burton Cyber Intelligence Infoblox [email protected] July 23, 2019 ABSTRACT This paper details data science research in the area of Cyber Threat Intelligence applied to a specific type of Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack. We study a DDoS technique prevalent in the Domain Name System (DNS) for which little malware have been recovered. Using data from a globally distributed set of a passive collectors (pDNS), we create a statistical classifier to identify these attacks and then use unsupervised learning to investigate the attack events and the malware that generates them. The first known major study of this technique, we discovered that current attacks have little resemblance to published descriptions and identify several previously unpublished features of the attacks. Through a combination of text and time series features, we are able to characterize the dominant malware and demonstrate that the number of global-scale attack systems is relatively small. 1 Introduction In the field of Cyber Security, there is a rich history of characterizing malicious actors, their mechanisms and victims, through the analysis of recovered malware1 and related event data. Reverse engineers and threat analysts take advantage of the fact that malware developers often unwittingly leave fingerprints in their code through the choice of libraries, variables, infection mechanisms, and other observables. In some cases, the Cyber Security Industry is able to correlate seemingly disparate pieces of information together and attribute malware to specific malicious actors. Identifying a specific technique or actor involved in an attack, allows the Industry to better understand the magnitude of the threat and protect against it. -

DNS Zones Overview

DNS Zones Overview A DNS zone is the contiguous portion of the DNS domain name space over which a DNS server has authority. A zone is a portion of a namespace. It is not a domain. A domain is a branch of the DNS namespace. A DNS zone can contain one or more contiguous domains. A DNS server can be authoritative for multiple DNS zones. A non-contiguous namespace cannot be a DNS zone. A zone contains the resource records for all of the names within the particular zone. Zone files are used if DNS data is not integrated with Active Directory. The zone files contain the DNS database resource records that define the zone. If DNS and Active Directory are integrated, then DNS data is stored in Active Directory. The different types of zones used in Windows Server 2003 DNS are listed below: Primary zone Secondary zone Active Directory-integrated zone Reverse lookup zone Stub zone A primary zone is the only zone type that can be edited or updated because the data in the zone is the original source of the data for all domains in the zone. Updates made to the primary zone are made by the DNS server that is authoritative for the specific primary zone. Users can also back up data from a primary zone to a secondary zone. A secondary zone is a read-only copy of the zone that was copied from the master server during zone transfer. In fact, a secondary zone can only be updated through zone transfer. An Active Directory-integrated zone is a zone that stores its data in Active Directory. -

Configuring DNS

Configuring DNS The Domain Name System (DNS) is a distributed database in which you can map hostnames to IP addresses through the DNS protocol from a DNS server. Each unique IP address can have an associated hostname. The Cisco IOS software maintains a cache of hostname-to-address mappings for use by the connect, telnet, and ping EXEC commands, and related Telnet support operations. This cache speeds the process of converting names to addresses. Note You can specify IPv4 and IPv6 addresses while performing various tasks in this feature. The resource record type AAAA is used to map a domain name to an IPv6 address. The IP6.ARPA domain is defined to look up a record given an IPv6 address. • Finding Feature Information, page 1 • Prerequisites for Configuring DNS, page 2 • Information About DNS, page 2 • How to Configure DNS, page 4 • Configuration Examples for DNS, page 13 • Additional References, page 14 • Feature Information for DNS, page 15 Finding Feature Information Your software release may not support all the features documented in this module. For the latest caveats and feature information, see Bug Search Tool and the release notes for your platform and software release. To find information about the features documented in this module, and to see a list of the releases in which each feature is supported, see the feature information table at the end of this module. Use Cisco Feature Navigator to find information about platform support and Cisco software image support. To access Cisco Feature Navigator, go to www.cisco.com/go/cfn. An account on Cisco.com is not required. -

Adopting Encrypted DNS in Enterprise Environments

National Security Agency | Cybersecurity Information Adopting Encrypted DNS in Enterprise Environments Executive summary Use of the Internet relies on translating domain names (like “nsa.gov”) to Internet Protocol addresses. This is the job of the Domain Name System (DNS). In the past, DNS lookups were generally unencrypted, since they have to be handled by the network to direct traffic to the right locations. DNS over Hypertext Transfer Protocol over Transport Layer Security (HTTPS), often referred to as DNS over HTTPS (DoH), encrypts DNS requests by using HTTPS to provide privacy, integrity, and “last mile” source authentication with a client’s DNS resolver. It is useful to prevent eavesdropping and manipulation of DNS traffic. While DoH can help protect the privacy of DNS requests and the integrity of responses, enterprises that use DoH will lose some of the control needed to govern DNS usage within their networks unless they allow only their chosen DoH resolver to be used. Enterprise DNS controls can prevent numerous threat techniques used by cyber threat actors for initial access, command and control, and exfiltration. Using DoH with external resolvers can be good for home or mobile users and networks that do not use DNS security controls. For enterprise networks, however, NSA recommends using only designated enterprise DNS resolvers in order to properly leverage essential enterprise cybersecurity defenses, facilitate access to local network resources, and protect internal network information. The enterprise DNS resolver may be either an enterprise-operated DNS server or an externally hosted service. Either way, the enterprise resolver should support encrypted DNS requests, such as DoH, for local privacy and integrity protections, but all other encrypted DNS resolvers should be disabled and blocked. -

Practical Domain Name System Security: a Survey of Common Hazards and Preventative Measures Nicholas A

Practical Domain Name System Security: A Survey of Common Hazards and Preventative Measures Nicholas A. Plante | [email protected] College of Computer and Information Science Northeastern University, Boston MA I. Introduction The Domain Name System (DNS) is a hierarchical database distributed around the world whose primary function is to translate human-readable domain names to numerical IP addresses for network lookup and communication. The current system was designed in 1984 by Paul Mockapetris to eliminate scalability problems that had become apparent with the previous name-to-IP mapping scheme, which involved maintenance of a single hosts file distributed to end hosts periodically. A vast improvement to its predecessor, DNS is well suited to its task of maintaining a relatively efficient, distributed set of name- to-IP mappings, but unfortunately leaves something to be desired in terms of security. DNS is a critical part of everyday Internet usage required by anyone who has ever checked email through their provider, surfed to a website, or used a chat application to discuss the latest happenings with friends or family. Despite its relative invisibility to the common user, DNS is a service that most every networked application depends on dearly. This being the case, it is an obvious target for manipulation by malicious users. It is also particularly susceptible to compromise due to the following reasons: - DNS uses the connectionless User Datagram Protocol (UDP) to convey information from authoritative servers to clients instead of its connection-oriented counterpart, TCP. This decision was made for a number of legitimate reasons, but in terms of security, it makes requests particularly susceptible to hijacking, and responses easy to spoof, as it is not subjected to the three-way handshake that is required to set up a TCP connection. -

Internet Governance Project

International internet Policy Priorities United States Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) [Docket No. 180124068–8068–01] RIN 0660–XC041 The Internet Governance Project (IGP) is a group of professors, postdoctoral researchers and students hosted at the Georgia Institute of Technology’s School of Public Policy. We conduct scholarly research, produce policy analyses and commentary on events in Internet governance, and bring our ideas and proposals directly into Internet governance processes. We also educate professionals and young people about Internet governance in various world regions. IGP welcomes NTIA’s broadly focused NOI on “International Internet Policy Priorities.” We believe that agency is asking many of the right questions and appreciate its desire to look for guidance from the public. Our response will follow the template of the NOI. I. THE FREE FLOW OF INFORMATION AND JURISDICTION A. What are the challenges to the free flow of information online? There are two distinct challenges to the free flow of information. The biggest and most fundamental is alignment,1 which is related to the issue of jurisdiction. Alignment refers to the attempt by national governments to assert sovereignty over cyberspace, by imposing exclusive territorial jurisdiction and national controls in a globally interoperable cyberspace. Data localization is one obvious example of a policy that seeks to achieve alignment, but the process is evident in multiple domains of Internet governance: in cybersecurity policy, trade policy, intellectual property protection and content regulation. In each case states erect barriers that 1 The concept of alignment was described in the book Will the Internet Fragment? (Polity Press, 2017). -

Reverse DNS What Is 'Reverse DNS'?

Reverse DNS Overview • Principles • Creating reverse zones • Setting up nameservers • Reverse delegation procedures What is ‘Reverse DNS’? • ‘Forward DNS’ maps names to numbers – svc00.apnic.net -> 202.12.28.131 • ‘Reverse DNS’ maps numbers to names – 202.12.28.131 -> svc00.apnic.net 1 Reverse DNS - why bother? • Service denial • That only allow access when fully reverse delegated eg. anonymous ftp • Diagnostics • Assisting in trace routes etc • SPAM identifications • Registration • Responsibility as a member and Local IR In-addr.arpa • Hierarchy of IP addresses – Uses ‘in-addr.arpa’ domain • INverse ADDRess • IP addresses: – Less specific to More specific • 210.56.14.1 • Domain names: – More specific to Less specific • delhi.vsnl.net.in – Reversed in in-addr.arpa hierarchy • 14.56.210.in-addr.arpa Principles • Delegate maintenance of the reverse DNS to the custodian of the address block • Address allocation is hierarchical – LIRs/ISPs -> Customers -> End users 2 Principles – DNS tree - Mapping numbers to names - ‘reverse DNS’ Root DNS net edu com arpa au apnic in-addr whoiswhois RIR 202202 203 210 211.. ISP 6464 22 .64.202 .in-addr.arpa Customer 2222 Creating reverse zones • Same as creating a forward zone file – SOA and initial NS records are the same as normal zone – Main difference • need to create additional PTR records • Can use BIND or other DNS software to create and manage reverse zones – Details can be different Creating reverse zones - contd • Files involved – Zone files • Forward zone file – e.g. db.domain.net • Reverse zone file – e.g. db.192.168.254 – Config files • <named.conf> – Other • Hints files etc. -

Ipv6-Ipsec And

IPSec and SSL Virtual Private Networks ITU/APNIC/MICT IPv6 Security Workshop 23rd – 27th May 2016 Bangkok Last updated 29 June 2014 1 Acknowledgment p Content sourced from n Merike Kaeo of Double Shot Security n Contact: [email protected] Virtual Private Networks p Creates a secure tunnel over a public network p Any VPN is not automagically secure n You need to add security functionality to create secure VPNs n That means using firewalls for access control n And probably IPsec or SSL/TLS for confidentiality and data origin authentication 3 VPN Protocols p IPsec (Internet Protocol Security) n Open standard for VPN implementation n Operates on the network layer Other VPN Implementations p MPLS VPN n Used for large and small enterprises n Pseudowire, VPLS, VPRN p GRE Tunnel n Packet encapsulation protocol developed by Cisco n Not encrypted n Implemented with IPsec p L2TP IPsec n Uses L2TP protocol n Usually implemented along with IPsec n IPsec provides the secure channel, while L2TP provides the tunnel What is IPSec? Internet IPSec p IETF standard that enables encrypted communication between peers: n Consists of open standards for securing private communications n Network layer encryption ensuring data confidentiality, integrity, and authentication n Scales from small to very large networks What Does IPsec Provide ? p Confidentiality….many algorithms to choose from p Data integrity and source authentication n Data “signed” by sender and “signature” verified by the recipient n Modification of data can be detected by signature “verification” -

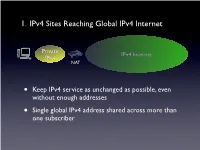

1. Ipv4 Sites Reaching Global Ipv4 Internet

1. IPv4 Sites Reaching Global IPv4 Internet Private IPv4 Internet IPv4 NAT • Keep IPv4 service as unchanged as possible, even without enough addresses • Single global IPv4 address shared across more than one subscriber SP IPv6 Network Private Tunnel for IPv4 (public, private, port-limited, etc....) IPv4 Internet IPv4 • Scenario #2 - Service Providers Running out of Private IPv4 space • IPv4 / IPv6 encapsulations/tunnels • Tunnels setup by DHCP, Routing, etc. between a GW and Router • Wherever the NAT lands, it is important that the user keeps control of it • Provides a path to delivering IPv6 SP IPv6 Network Tunnel for IPv4 (public, private, port-limited, etc....) IPv4 Internet • Scenario #3a “Wireless Greenfield” • IPv4 / IPv6 encapsulations/tunnels • Tunnels setup between a host and a Router • IPv4 binding for host applications, transport over IPv6 • Wherever the NAT lands, it is important that the user keeps control of it 3 - 5 Translation Options IPv6 Internet IPv4 Internet IPv6 IPv4 My IPv6 Network IPv6 Internet IPv4 Internet • “Scenario #3” • NAT64/DNS64.... - Stateful, DNSSEC Challenges, DNS64 location, etc. My IPv6 Network IPv6 Internet IPv4 Internet • “Scenario #5” • IVI - NAT-PT..... Expose only certain IPv6 servers, etc. MY IPv4 Network IPv6 Internet IPv4 Internet • “Scenario #4” • NAT64 - 1:1, Stateless, DNSSEC OK, no DNS64 MY IPv4 Network IPv6 Internet IPv4 Internet • Already solved by existing transition mechanisms?? (teredo, etc). Scenarios 1 - 5 1. IPv4 Sites Reaching Global IPv4 Internet Private IPv4 Internet IPv4 NAT • Keep IPv4 service as unchanged as possible, even without enough addresses • Single global IPv4 address shared across more than one subscriber 2. Service Providers Running out of Private IPv4 space ISP Private IPv4 Private Network IPv4 IPv4 Internet • Service Providers with large, privately addressed, IPv4 networks • Organic growth plus pressure to free global addresses for customer use contribute to the problem • The SP Private networks in question generally do not need to reach the Internet at large 3. -

Proactive Cyberfraud Detection Through Infrastructure Analysis

PROACTIVE CYBERFRAUD DETECTION THROUGH INFRASTRUCTURE ANALYSIS Andrew J. Kalafut Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science Indiana University July 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Minaxi Gupta, Ph.D. Committee (Principal Advisor) Steven Myers, Ph.D. Randall Bramley, Ph.D. July 19, 2010 Raquel Hill, Ph.D. ii Copyright c 2010 Andrew J. Kalafut ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii To my family iv Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my advisor, Minaxi Gupta. Minaxi’s feedback on my research and writing have invariably resulted in improvements. Minaxi has always been supportive, encouraged me to do the best I possibly could, and has provided me many valuable opportunities to gain experience in areas of academic life beyond simply doing research. I would also like to thank the rest of my committee members, Raquel Hill, Steve Myers, and Randall Bramley, for their comments and advice on my research and writing, especially during my dissertation proposal. Much of the work in this dissertation could not have been done without the help of Rob Henderson and the rest of the systems staff. Rob has provided valuable data, and assisted in several other ways which have ensured my experiments have run as smoothly as possible. Several members of the departmental staff have been very helpful in many ways. Specifically, I would like to thank Debbie Canada, Sherry Kay, Ann Oxby, and Lucy Battersby. -

Aerohive Configuration Guide: RADIUS Authentication | 2

Aerohive Configuration Guide RADIUS Authentication Aerohive Configuration Guide: RADIUS Authentication | 2 Copyright © 2012 Aerohive Networks, Inc. All rights reserved Aerohive Networks, Inc. 330 Gibraltar Drive Sunnyvale, CA 94089 P/N 330068-03, Rev. A To learn more about Aerohive products visit www.aerohive.com/techdocs Aerohive Networks, Inc. Aerohive Configuration Guide: RADIUS Authentication | 3 Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 IEEE 802.1X Primer................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Example 1: Single Site Authentication .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Step 1: Configuring the Network Policy ..............................................................................................................................................................7 Step 2: Configuring the Interface and User Access .........................................................................................................................................7 Step 3: Uploading the Configuration and Certificates .................................................................................................................................... -

Oracle Berkeley DB Installation and Build Guide Release 18.1

Oracle Berkeley DB Installation and Build Guide Release 18.1 Library Version 18.1.32 Legal Notice Copyright © 2002 - 2019 Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. Berkeley DB, and Sleepycat are trademarks or registered trademarks of Oracle. All rights to these marks are reserved. No third- party use is permitted without the express prior written consent of Oracle. Other names may be trademarks of their respective owners. If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, delivered to U.S. Government end users are "commercial computer software" pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency-specific supplemental regulations. As such, use, duplication, disclosure, modification, and adaptation of the programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, shall be subject to license terms and license restrictions applicable to the programs.