Thammasat Review H 84

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Head Office Nr. Bhumkar Chowk, Wakad, Pune. Contact-09096790230 Branch Nr, Karve Statue, Kothrud, Pune

Current Affairs January -2016 Head Office Nr. Bhumkar Chowk, Wakad, Pune. Contact-09096790230 Branch Nr, Karve Statue, Kothrud, Pune. Contact-09604001144 Mindchangers Academy,Pune. Page 1 Current Affairs January -2016 INDIAN AFFAIRS Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs increase in the budget amount for grid-connected solar rooftop systems to Rs. 5,000 crore from Rs.600 crore for 2019-2020. Amaravati will get India’s first ever underwater tunnel under the river Krishna -3km long. Pakistan’s Singer Adnan Sami gets Indian Citizenship Goa set up Investment Promotion Board (IPB) for fast approvals to industrial proposals - cleared 62 proposals with investment of Rs 5,200 crore. Government decided to merge the ministry of overseas Indian affairs (MOIA) with the external affairs ministry. Telangana becomes the first state in the country to legally accept Electronic motor insurance policies e-Vahan Bima -under Motor Vehicle Act 1988 Alstom the French transportation equipment maker rolled out the first set of railway coaches for the Kochi Metro project - Chennai metro the first. PM Narendra Modi inaugurated the 103rd Indian Science Congress in Mysore,Karnataka Theme – Science & Technology for Indigenous Development in India 5 key bills assented by Prez Pranab Mukherjee - Article 111 1. Atomic Energy (Amendment) Act Payment of Bonus (Amendment) Act, 2015 2. Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2015 3. Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Act, 2015 4. Commercial Courts, Commercial Division and Commercial Appellate Division of High Courts Act State election commissioner (SEC) Ashok Kumar Chauhan announced that toilets will be mandatory requirement for eligibility to contest panchayat elections in Bihar. -

Annual Report 2014

VweJssm&Mcla 9nie^m U cm al ^h u yixia tlfm Annual Report 2014 G w d m ti Preface About VIF Our Relationship Worldwide Activities Seminars & Interactions . International Relations & Diplomacy . National Security & Strategic Studies . Neighbourhood Studies . Economic Studies . Historical & Civilisational Studies Reaching Out . Vimarsha . Scholars' Outreach Resource Research Centre and Library Publications VIF Website & E-Journal Team VIF Advisory Board & Executive Council Finances P ^ e la c e Winds of Change in India 2014 was a momentous year for India that marked the end of coalition governments and brought in a Government with single party majority after 40 years with hopes of good governance and development. Resultantly, perceptions and sentiments about India also improved rapidly on the international front. Prime Minister Modi’s invite to SAARC heads of states for his swearing in signified his earnestness and commitment to enhancing relationships with the neighbours. Thereafter, his visits to Bhutan, Japan, meeting President Xi Jinping and later addressing the UN and summit with President Obama underlined the thrust of India’s reinvigoration of its foreign and security policies. BRICS, ASEAN and G-20 summits were the multilateral forums where India was seen in a new light because of its massive political mandate and strength of the new leadership which was likely to hasten India’s progress. Bilateral meets with Myanmar and Australian leadership on the sidelines of ASEAN and G-20 and visit of the Vietnamese Prime Minister to India underscored PM Modi’s emphasis on converting India’s Look East Policy to Act East Policy’. International Dynamics While Indian economy was being viewed with dismay in the first half of the year, now India is fast becoming an important and much sought after destination for investment as the change of government has engendered positive resonance both at home and abroad. -

India's Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 22 India’s Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S.-India Security Cooperation on Domestic Counterinsurgency by Thomas F. Lynch III Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for Technology and National Security Policy. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Hard-line communists, belonging to the political group Naxalite, pose with bows and arrows during protest rally in eastern Indian city of Calcutta December 15, 2004. More than 5,000 Naxalites from across the country, including the Maoist Communist Centre and the Peoples War, took part in a rally to protest against the government’s economic policies (REUTERS/Jayanta Shaw) India’s Naxalite Insurgency India’s Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S.-India Security Cooperation on Domestic Counterinsurgency By Thomas F. Lynch III Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. -

Contemporary Naxal Movement in India: New Trends, State

Innovative Research | Independent Analysis | Informed Opinion Contemporary Naxal Movement in India New Trends, State Responses and Recommendations Rajat Kujur IPCS Research Paper 27 May 2013 Programme on Armed Conflicts in South Asia (ACSA) CONTEMPORARY NAXAL MOVEMENT IN INDIA Abstract This paper makes an attempt to map the Maoist conflict in its present state of affairs and while describing its present manifestations, the past links have always been revisited. The paper also attempts to systematically decode the Maoist strategies of continuity and discontinuity. Broadly speaking, this paper has four segments. The report draws a broad outline of the contemporary Maoist conflict, identifies contemporary trends in the Naxal Movement, critiques the responses of the state strategies and finally provides policy recommendations. About the Institute The Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies (IPCS), established in August 1996, is an About the Author independent think tank devoted to research on Dr. Rajat Kumar Kujur teaches peace and security from a Political Science in the P.G. South Asian perspective. Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Its aim is to develop a Sambalpur University, Odisha. He comprehensive and has written extensively for IPCS alternative framework for on Maoist Conflict and currently Contents peace and security in the is also a Visiting Fellow of the Institute. Dr. Kujur specializes on region catering to the the area of Political Violence and Militarization and Expansion changing demands of has done his Ph.D from JNU, New 03 national, regional and Delhi on “Politics of Maoism”. He has coauthored a book titled Contemporary Trends 05 global security. “Maoism in India: Reincarnation of Ultra Left Extremism in Twenty 15 First Century” which was Responding to the Maoist @ IPCS, 2013 published by Routledge, London Challenge in 2010 Policy Recommendations 21 B 7/3 Lower Ground Floor, Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi 110029, INDIA. -

RESEARCH PAPER – No

RESEARCH PAPER April 20th, 2020 CENTRAL ARMED POLICE FORCES IN INDIA: BETWEEN GROWTH AND VERSATILITY Dr Damien CARRIÈRE Post-doctoral researcher at IRSEM ABSTRACT Composed of six specialised corps under the responsibility of the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Central Armed Police Forces in India (CAPF) count in their ranks close to 980,000 men and women. Primarily responsible for border guarding, counter-terror- ism, law enforcement, and counterinsurgency, the CAPF have seen their workforce and budget grow over the past twenty years. Particularly active in Kashmir, in the North-East, and in many central states afflicted by a Maoist rebellion, they are de- ployed wherever the Central State deems it necessary and where state police forces, more often than not understaffed, are overwhelmed. As the armed wing of the State and pillar of India’s domestic security, the CAPF also intervene during natural disasters – No. 94 in order to rescue populations. CONTENT Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 2 The structure of the CAPF ........................................................................................................... 3 Forces deployed on all fronts .................................................................................................... 9 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 14 Annex .......................................................................................................................................... -

Left-Wing Extremism in India- Revisiting

Policy Brief #29 23 July 2019 Left-wing Extremism in India: Revisiting the ‘new’ Strategy Bibhu Prasad Routray Abstract The National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government in New Delhi, in its second term, is making renewed attempts to end left-wing extremism (LWE). The broad parameters of the new strategy consist of plans to target the extremists by deploying more forces in the affected states and also to pursue the over-ground sympathizers of the movement in urban areas. The strategy does not vary qualitatively much from the one pursued by the previous Home Ministry under Rajnath Singh and even his predecessor P Chidambaram. Unless the governance deficit is addressed and a comprehensive national strategy on LWE is initiated, mere force-centric methods cannot bring a permanent solution to the problem. Ground Situation According to assessments of India’s Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), the LWE (also interchangeably referred to as Naxals or Maoists) outfit, Communist Party of India (CPI-Maoist) has weakened significantly. Its ability to orchestrate violence has reduced and its influence has been restricted to 15 percent of the country1 comprising few pockets of states like Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Bihar, and Jharkhand. On 10 July 2019, the Union Minister of State for Home Affairs, G. Kishan Reddy said in the Rajya Sabha (Upper House of India’s Parliament)2 that violent incidents perpetrated by the LWE cadres declined from 2258 in 2009 to 833 in 2018. The resultant fatalities declined from 1005 in 2010 to 240 in 2018. He also stated that the geographical spread of LWE has declined from 223 Maoist affected districts in 2008 to a mere 60 in 2018. -

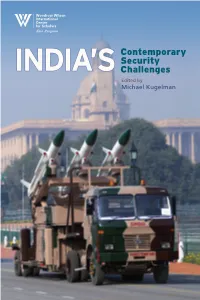

INDIA'scontemporary Security Challenges

Contemporary Security INDIA’S Challenges Edited by Michael Kugelman INDIa’s Contemporary SECURITY CHALLENGES Essays by: Bethany Danyluk Michael Kugelman Dinshaw Mistry Arun Prakash P.V. Ramana Siddharth Srivastava Nandini Sundar Andrew C. Winner Edited by: Michael Kugelman ©2011 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. www.wilsoncenter.org Available from : Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org ISBN 1-933549-79-3 The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, es- tablished by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mis- sion is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and international affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan institution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publi- cations and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advi- sory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television, and the monthly news-letter “Centerpoint.” For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. -

Mission Saranda

MISSION SARANDA MISSION SARANDA A War for Natural Resources in India GLADSON DUNGDUNG with a foreword by FELIX PADEL Published by Deshaj Prakashan Bihar-Jharkhand Bir Buru Ompay Media & Entertainment LLP Bariatu, Ranchi – 834009 © Gladson Dungdung 2015 First published in 2015 All rights reserved Cover Design : Shekhar Type setting : Khalid Jamil Akhter Cover Photo : Author ISBN 978-81-908959-8-9 Price ` 300 Printed at Kailash Paper Conversion (P) Ltd. Ranchi - 834001 Dedicated to the martyrs of Saranda Forest, who have sacrificed their lives to protect their ancestral land, territory and resources. CONTENTS Glossary ix Acknowledgements xi Foreword xvii Introduction 01 1. A Mission to Saranda Forest 23 2. Saranda Forest and Adivasi People 35 3. Mining in Saranda Forest 45 4. Is Mining a Curse for Adivasis? 59 5. Forest Movement and State Suppression 65 6. The Infamous Gua Incident 85 7. Naxal Movement in Saranda 91 8. Is Naxalism Taking Its Last Breath 101 in Saranda Forest? 9. Caught Among Three Sets of Guns 109 10. Corporate and Maoist Nexus in Saranda Forest 117 11. Crossfire in Saranda Forest 125 12. A War and Human Rights Violation 135 13. Where is the Right to Education? 143 14. Where to Heal? 149 15. Toothless Tiger Roars in Saranda Forest 153 16. Saranda Action Plan 163 Development Model or Roadmap for Mining? 17. What Do You Mean by Development? 185 18. Manufacturing the Consent 191 19. Don’t They Rule Anymore? 197 20. It’s Called a Public Hearing 203 21. Saranda Politics 213 22. Are We Indian Too? 219 23. -

Operation Green Hunt

Operation Green Hunt -a perspective of political economy Anand Teltumbde Convention on Operation Green Hunt and Democratic Rights Mumbai 16 January 2010 is the single biggest internal “Naxalism security challenge” Singh,ever Primefaced Minister by our in 2006 country Manmohan - Dr. “Naxalism is the greatest internal security threat to India” … and to development” - Dr. Manmohan Singh, Prime Minister in 2009 - are nothing” but cold “Naxalites blooded murders -Advt. issued by the Home Ministry Threat to Internal Security of Rural India of Poor Peasants, INDIA Farmers, Landless labourers, Dalits, Adivasis…? ? Urban India of Slum and pavementWhich IndiaDwellers, Casual Workers, Contract Laboureres, … ? Middle India of swelling Middle Classes? Corporate India of Corporate Honchos? Globalizing India of Dollar Millionaires and Billionaires? Surely, it is a Threat to the India of handful Globalist Elites! Nothing but cold-blooded murderers… Human life is sacred No one can and should defend destruction of human life True, huge loss of life has taken place in Naxal conflict … both by Maoists and Security Personnel Statistics show comparable figures of Killings by both.. According to Chhattisgarh Police, In 2008, 212 people were killed.. 63 Sec. and 52 Naxals.. In 2007, 369 people were killed.. 124 Sec. and 64 Naxals… In 2006, 385 people were killed… 39 Sec. and 69 Naxals… Civilian casualty is far more and who did it is not known! Nothing but cold-blooded murderers…. What about Fake encounters? Custodial deaths? Extra-judicial killings? and Structural -

08 Eric Scanlon DOI.Indd

Asian Journal of Peacebuilding Vol. 6 No. 2 (2018): 335-351 doi: 10.18588/201811.00a038 Research Note Fifty-One Years of Naxalite-Maoist Insurgency in India: Examining the Factors that Have Influenced the Longevity of the Conflict Eric Scanlon The Naxalite-Maoist uprising in India has for fifty-one years continued almost unabated. Today Maoist rebels have a substantial presence in at least ten of India’s twenty-nine states and the Indian government has repeatedly stated that it remains the most potent threat to stability that the Indian state faces. This research note examines the existing literature and local primary sources to explore the economic, social, and military factors that have influenced the longevity of this conflict. It details how a fifty-one year conflict has continued almost unmitigated in a country that has the military might that India commands. Keywords India, Naxalites, Maoism, conflict, longevity Introduction May 2018 marked the fifty-first anniversary of the peasant revolt in a little village called Naxalbari, in the Indian state of West Bengal. What seemed like a local uprising soon spread rapidly throughout India and took on a Marxist and Maoist character. As the uprising began in Naxalbari, the insurgents were nicknamed Naxalites, a name which has stuck to this day. The Maoist rebellion has continued almost unabated and today Maoist rebels have a significant presence in ten of India’s twenty-nine states (Ministry of Home Affairs 2016). At the height of the Naxalite rebellion in the 2000s it is estimated that they controlled nearly 10 million hectares of mainly forested land. -

Sacm-Nov 2019

SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF PEACE AND CONFLICT THURSDAY, 7 NOVEMBER 2019 South Asia Conflict Monitor monthly newsletter on terrorism, violence and armed conflict… CONTENT SRI LANKA: Presidential elections: Will the minorities become King maker? NAXAL Movement in India: A Historical Anthology SRI LANKA: “Presidential elections: Will the minorities become King maker?” NEWS ROUNDUP (October 2019) As Sri Lanka is gearing towards the eighth against Sajith. Since both AFGHANISTAN: P. 9-11 presidential elections on November 16, national Sajith and GR are from BANGLADESH: P. 11-12 security, foreign policy and foreign investments Sinhala community and INDIA: P. 13-15 in infrastructure projects and minority issues are have almost flagged similar MALDIVES: P. 15 once again dominating the political discourse in issues in their election NEPAL : P. 16-17 the country. Although a record 35 candidates manifestos, Sinhala vote PAKISTAN: P. 17-18 have registered for this election, the electoral could be equally divided SRI LANKA: P. 18-19 debate has been mostly dominated by the UNP between them. In that case, candidate, Sajith Premadasa, and SLPP minority groups’ support to candidate, Gotabaya Rajapaksa (GR). The JVP anyone of them in the and the NPM could be closer to these two elections would be crucial. Most importantly, the parties. Other candidates are allegedly minority groups like Tamils and Muslims feel participating as proxy or dummy candidates comfortable with the UNP than the SLPP due fielded by the SLPP to share the vote percentage to GR’s association with radical Buddhist groups of UNP candidates. like Bodu Bala Sena (BBS). But GR could get slightly more votes given the global trend in The table reflects that there will be a strong favor of nationalists, and minority consolidation contest between the UNP and the SLPP in this in favor of Sajith could put him as a net vote election. -

A Modern Insurgency: India's Evolving Naxalite Problem

Number 140 April 8, 2010 A Modern Insurgency: India’s Evolving Naxalite Problem William Magioncalda The April 6, 2010, ambush in Chhattisgarh state, killing 76 members of the Central Reserve Police Force, marks the deadliest attack upon Indian security forces since the foundation of the “Naxalite” movement. Formed from a 1967 split within the Communist Party of India (Marxist), the insurgency has been responsible for decades of violence throughout eastern and central India’s “Red Corridor.” These loosely affiliated Maoist rebels claim to fight on behalf of the landless poor, virulently opposing the injustice and oppression of the Indian state. In response to attacks on police officers, government officials, and landlords, India has employed an assortment of counterinsurgency strategies that, over the years, have met varied levels of success. As the modern Naxalite movement continues to develop, the Indian government faces new complications related to one of its most destabilizing internal security challenges. Adequately addressing this threat will prove essential in solidifying India’s status as a rising world power, as well as demonstrating its capacity to effectively combat militancy. Persistent Threat: The first 25 years of the Naxalite insurgency were characterized by the communist principles on which the movement was founded. Fighting for land reform, the rebels gained support from the impoverished rural populations of eastern and central India. The Maoist rebellion quickly adopted violence and terror as the core instruments of its struggle against the Indian authority. Primary targets included railway tracks, post offices, and other state infrastructure, demonstrating the Maoists’ commitment to undermining a central government that they believed exploited low castes and rural populations.