Passive Ventilation for Indoor Comfort: a Comparison of Results from Monitoring and Simulation for a Historical Building in a Temperate Climate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modulating Natural Ventilation to Enhance Resilience187 Through Modifying Nozzle Profiles

MODULATING NATURAL VENTILATION TO ENHANCE RESILIENCE THROUGH MODIFYING NOZZLE PROFILES Exploring Rapid Prototyping Through 3D-Printing NIKITA BHAGAT1, ZOFIA RYBKOWSKI2, NEGAR KALANTAR3, MANISH DIXIT4, JOHN BRYANT5 and MARYAM MANSOORI6 1,2,5Department of Construction Science, College of Architecture, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3,6Department of Architecture, College of Architecture, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843 3,6{kalantar|maryammansoori}@tamu.edu 4Department of Construction Science; College of Architecture, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843 [email protected] Abstract. The study aimed to develop and test an environmentally friendly, easily deployable, and affordable solution for socio-economically challenged populations of the world. 3D-printing (additive manufacturing) was used as a rapid prototyping tool to develop and test a façade system that would modulate air velocity through modifying nozzle profiles to utilize natural cross ventilation techniques in order to improve human comfort in buildings. Constrained by seasonal weather and interior partitions which block the ability to cross ventilate, buildings can be equipped to perform at reduced energy loads and improved internal human comfort by using a façade system composed of retractable nozzles developed through this empirical research. This paper outlines the various stages of development and results obtained from physically testing different profiles of nozzle-forms that would populate the façade system. In addition to optimizing nozzle profiles, the team investigated the potential of collapsible tube systems to permit precise placement of natural ventilation directed at occupants of the built space. Keywords. Natural ventilation; Wind velocity; Rapid prototyping; 3D-printing; Nozzle profiles. -

Small-Scale Solar Heating and Cooling Systems

Small-Scale Solar Heating and Cooling Systems Package Systems for Combined Air Conditioning, Domestic Hot Water Preparation and Space Heating Standardized System Solutions Package Solutions on the Market Solar thermal domestic hot water heating (DHW) DHW & space heating Solar Combi & space cooling Solar Combi+ February 2010 Table of Contents What is a Solar Combi Plus System? ....................................3 Most Promising Climatic Regions .........................................4 Suitable Collector Technology .............................................6 Standard System Configurations .........................................9 Recommendations on System Design................................. 11 Package System - Climatewell........................................... 14 Package System - SOLution.............................................. 16 Package System - SorTech ............................................... 18 Contact .......................................................................... 20 http://www.solarcombiplus.eu Page 2 of 20 What is a Solar Combi Plus System? Solar combi plus systems use heat from solar thermal collectors to provide heating in winter, cooling in summer and domestic hot water (DHW) all year round. The figure below sketches the main components, which make up a typical system: (i) the solar thermal collector to provide the heat usually backed up by an auxiliary heat source, (ii) a storage tank can either be installed on the hot side, as shown in the figure, on the cold side or on both, (iii) a domestic -

Passive Downdraft Systems: a Vision for Ultra-Low Energy Heating, Cooling and Ventilation

Passive Downdraft Systems: A Vision for Ultra-Low Energy Heating, Cooling and Ventilation Andrew Corney, WSP Flack + Kurtz – Built Ecology ABSTRACT In modern buildings, fans used to move air around for ventilation, heating and cooling represent a significant component of energy consumption. As a means of reducing this energy consumption, buildings with conventional overhead air conditioning systems have pushed the limits on air quality and thermal comfort by limiting the quantity of air supplied. Similarly, natural ventilation systems, with their limited capacity to provide temperature control to meet expectations, especially in cooling are very rarely adopted as design solutions outside of the residential sector, even though they can be extremely energy efficient. Some designers have sought to overcome this by providing hybrid systems with both natural ventilation and air conditioning backup. Often the cost of two systems results in both systems being or poorer quality with the result still being a building of average performance. This paper reviews new techniques in a fourth way – enhanced natural ventilation through the use of the passive downdraft, also known as buoyancy HVAC system. The approach has the potential to significantly reduce building energy and enhance air quality (through significantly increased outside air rates (P. Wargocki et al, 2000)) in many building types and especially in relatively mild climates. Introduction Just as the use of natural ventilation is as old as buildings themselves, the concept of using buoyancy forces is also thousands of years old. In ancient Persia, bagdir towers combined with water for evaporation were used to capture wind and use it to push and pull ventilation through buildings in the hot summers, cooling the air as it entered the space. -

High-Rise Social Housing in Hot-Humid Climates: Towards an ‘Airhouse’ Standard for Comfort

applied sciences Article High-Rise Social Housing in Hot-Humid Climates: Towards an ‘Airhouse’ Standard for Comfort Cristina Gonzalez-Longo * and Mohd Firrdhaus Mohd Sahabuddin Department of Architecture, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow G1 1XJ, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-7973418279 Received: 20 October 2019; Accepted: 16 November 2019; Published: 20 November 2019 Featured Application: The results of this research can be applied to the ongoing social housing construction program in Malaysia. Abstract: The pressure to provide social housing in a fast and economic way, as well as outdated regulations, constrain the design of these buildings, having serious implications for the comfort of occupants and the environment. This becomes more critical in hot-humid climates, such as Malaysia, with uniformly high temperature and humidity and low wind speeds. In its capital, Kuala Lumpur, an extensive program of construction for high-rise social housing is being carried out, however, shortly after the flats are occupied, or as soon as they can afford it, the residents fit wall mounted air conditioning units. This research started by looking at Malay vernacular architecture and the traditional strategies for ventilation and cooling. After a review of current building regulations and green tools employed in the country, two campaigns of fieldwork were carried out to assess the actual indoor and outdoor thermal and air quality conditions in the buildings, which were found to be inadequate for both the local regulations and international recommendations. The fieldwork also allowed the identification of the critical design issues to address. -

Development of Passive Cooling at the Gobabeb Research & Training

Development of Passive Cooling at the Gobabeb Research & Training Centre and Surrounding Communities By: Jackson Brandin Neel Dhanaraj Zachary Powers Douglas Theberge Project Number: 41-NW1-ABMC Development of Passive Cooling at the Gobabeb Research & Training Centre and Surrounding Communities An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By: Jackson Brandin Neel Dhanaraj Zachary Powers Douglas Theberge Date: 12 October 2018 Report Submitted to: Eugene Marais Gobabeb Research and Training Centre Professors Nicholas Williams, Creighton Peet, and Seeta Sistla Worcester Polytechnic Institute Abstract The Gobabeb Research and Training Centre of the Namib Desert, Namibia has technology rooms that overheat. We were tasked to passively cool these rooms. We acquired contextual information and collected temperature data to determine major heat sources to develop a solution. We concluded that the sun and internal technology were the major sources of heat gain. Based on prototyping, we recommend the GRTC implement evaporative cooling, shading, reflective paints, insulation, and ventilation methods to best cool their buildings. Additionally, we generalized this process for use in surrounding communities. iii Acknowledgements Mr. Eugene Marais (Sponsor) - We would like to thank you for proposing this project, and providing excellent guidance in our research. Dr. Gillian Maggs-Kӧlling - We would like to thank you for making our experience at the GRTC meaningful. Mrs. Elna Irish - We would like to thank you for arranging transportation, housing, and general guidance of the inner workings of the GRTC. Gobabeb Research and Training Centre Facilities Staff - We would like to thank you for working closely with us in accomplishing all of our solution testing. -

Passive Cooling and Human Comfort

Passive Cooling and Human Comfort Author Fairey, P.W. Publication Number FSEC-DN-5-81 Copyright Copyright © Florida Solar Energy Center/University of Central Florida 1679 Clearlake Road, Cocoa, Florida 32922, USA (321) 638-1000 All rights reserved. Disclaimer The Florida Solar Energy Center/University of Central Florida nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the Florida Solar Energy Center/University of Central Florida or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the Florida Solar Energy Center/University of Central Florida or any agency thereof. DesignNote Passive cooling and human comfort P.W. Fairey Florida Solar Energy Center Comfort within buildings is primarily controlled by dew point. When air is cooled to its dew point it is at four major factors: air temperature, mean radiant 100 percent relative humidity. This saturation point is temperature, humidity and airflow. Each can have a represented by the outer, curved boundary of the dominating effect. Their effects are not necessarily psychrometric chart. additive and practically never linear. There are, addi- The air temperature represented by the horizontal tionally, other factors which affect comfort including axis of the psychrometric chart is known as the dry clothing, activity level and climatization. -

City of Vancouver — Passive Design Toolkit

Passive Design Toolkit Passive Design Toolkit City of Vancouver — Passive Design Toolkit Message from the Mayor Vancouver City Council has taken an The Passive Design Toolkits will serve as a resource important first step toward our goal to the development industry, and as a framework for of becoming the greenest city in the the City’s Planning department to review and update world, as the first jurisdiction in North its design guidelines. Passive design elements, when America to go beyond green building evaluated in terms of relative cost and effectiveness, codes and use architecture itself to have been shown to reduce a building’s energy reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs). demand by as much as 50 percent. More than half of all GHG emissions in Vancouver The new Toolkits will help us create a more sustainable come from building operations, so the City has set a architectural form across the city, while improving target that all new construction will be GHG neutral by the comfort of the people who live and work in new 2030, through carbon-neutral measures in areas such buildings. as lighting and heating technologies. Gregor Robertson Message from BC Hydro BC Hydro is a proud supporter of the Passive Design We thank you for using this Toolkit in your project, Toolkits for the City of Vancouver. and congratulate the City of Vancouver for providing leadership in helping designers create the buildings of We recognize that part of providing clean energy for tomorrow in BC today. generations is helping British Columbians build Power Smart high performance buildings. Lisa Coltart, Executive Director Power Smart and Customer Care Prepared by: July 2009 Cobalt Engineering Vladimir Mikler, MSc, P.Eng., LEED® AP Albert Bicol, P.Eng., LEED® AP Cover Photo: IBI Group/Henriquez Partners Architects Beth Breisnes Photographer: Nic Lehoux Hugh es Condon Marler : Architects Hand Illustrations: Matthew Roddis Urban Design Michel Labrie, MAIBC, MOAQ, MRAIC, LEED® AP Passive Design Toolkit Contents 1. -

Passive Solar Heating & Cooling Manual, Part 1 of 4

http://www.azsolarcenter.org/tech-science/solar-architecture/passive-solar-design-manual/passive- solar-design-manual-intro.html Passive Solar Heating & Cooling Manual, Part 1 of 4 NOTE: Booklet available in Microsoft Word format, RTF format and PDF. Published by Rodale Press, Inc., 1980. A project of Western SUN Arizona and Western Solar Utilization Network. Introduction to Solar Energy The sun's energy arrives on earth in the primary form of heat and light. Other aspects of solar radiation are less easily perceived and their detection often requires sophisticated equipment. All solar radiation travels through space in waves, and it is the length of these waves (the shortest is less than a millionth of an inch, the longest more than a thousand yards) by which all solar radiation is classified. The aggregate of all radiation aspects of the sun is called the solar spectrum. There are two important facets about the solar spectrum. 1. While the sun emits radiation in all wavelengths, it is the short wavelength radiation that accounts for the majority of energy in the solar spectrum. For example, the portion of the spectrum perceived as the visible light is a relatively small segment compared to the variety of spectrum wavelengths, yet accounts for 46 percent of the energy radiating from the sun. Another 49 percent, that which is perceived as heat, is derived from the infrared band of the spectrum. 2. The proportion of different wavelengths in the solar spectrum does not change and therefore the energy output of the sun remains constant. A measurement of this phenomenon is known as the Solar Constant, defined as the amount of heat energy delivered by solar radiation to a square foot of material set perpendicular to the sun’s rays for one hour at the outer edge of the earth’s atmosphere. -

Physical Model and Design Rules for the Optimization of Solar Chimney Systems

U. Dietrich, Int. J. of Energy Prod. & Mgmt., Vol. 3, No. 4 (2018) 307–324 PHYSICAL MODEL AND DESIGN RULES FOR THE OPTIMIZATION OF SOLAR CHIMNEY SYSTEMS UDO DIETRICH REAP research group (Resource Efficiency in Architecture and Planning), HafenCity University Hamburg, Germany. ABSTRACT Natural ventilation is a basic quantity to reach comfort in passively acting buildings. It delivers not only fresh air to breath but can also be used to temper the room if the indoor temperature is above the outdoor one. Driving forces are temperature differences (buoyancy) and wind. However, both may be weak in hot and especially humid locations. A solar chimney uses solar radiation to heat up the exhausted air and to increase buoyancy, thus could help to improve that situation at least during the daytime. Nevertheless, the implementation of solar chimneys is quite rare. It may be that the idea to use heat to cool and ventilate a building seems strange. The literature reports about the potential of solar chimneys, characteristics like vol- ume flow and temperatures are measured or simulated. Though, the findings of these publications are based on a special geometry and provide not enough detailed information about the optimized shape (width, height, length, etc.) of solar chimneys. To overcome that situation, this paper presents general design rules for the geometry of solar chimney systems that could be adapted to existing or newly erected buildings. A solar chimney system is assumed as composed by three components: An absorber as the main part to reach a higher temperature, a stack extension on top for further accel- eration of the exhausted air, and a stack at the bottom connected to the (lower) storeys that should be ventilated. -

Engineering Technical Information System

ENGINEERING TECHNICAL FIELD NOTESTECHNICAL REPORTS DATA RETRIEVALMANAGEMENT INFORMATION PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT SYSTEM -Poll VOLUME 12 NUMBER 4 ield Notes NEW DEVELOPMENT IN CLEARING ROADS PRACTICAL SOLAR APPLICATIONS IMPROVE ENERGY EFFICIENCY IN FOREST SERVICE BUILDINGS FACILITIES WASHINGTON OFFICE NEWS FOREST SERVICE APRIL 1980 s sw4 US U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE 11ýS ENGINEERING FIELD NOTES Volume 12 Number 4 Information this contained in publication has been developed for guidance of employees of the States United Department of Agriculture-Forest Service its contractors and its cooperating Federal and State agencies. The Department of Agriculture assumes no respon-sibilityfor the interpretation or use of this -information by other than its own employees. The use of trade firm or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval of any product or service by the United States Department of Agriculture to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. text in the The publication represents the personal opinions of the respective author and must not be construed as recommended or approved procedures mandatory instructions or references. Because the policy except by FSM of type of material in the publication all technicians should read each engineers and engineering issue however this publication is not intended exclusively for engineers. FOREST SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Washington D.C. 20013 III A NEW DEVELOPMENT IN CLEARING ROADS Tom L. Condos Civil Engineer Tahoe National Forest An innovative product is now on the market that can cut clearing costs and timber sale road construction time. -

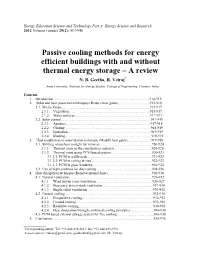

Passive Cooling Methods for Energy Efficient Buildings with and Without Thermal Energy Storage – a Review

Energy Education Science and Technology Part A: Energy Science and Research 2012 Volume (issues) 29(2): 913-946 Passive cooling methods for energy efficient buildings with and without thermal energy storage – A review N. B. Geetha, R. Velraj* Anna University, Institute for Energy Studies, College of Engineering, Chennai, India. Contents 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………..914-915 2. Solar and heat protection techniques (Reduce heat gains)……………………...915-919 2.1. Microclimate………………………………………………………………..915-917 2.1.1. Vegetation…………………………………………………………..915-917 2.1.2. Water surfaces………………………………………………………917-917 2.2. Solar control…………………………………………………………………917-919 2.2.1. Aperture……………………………………………………………..917-918 2.2.2. Glazing………………………………………………………………918-919 2.2.3. Insulation…………………………………………………………….919-919 2.2.4. Shading………………………………………………………………919-919 3. Heat modulation or amortization technique (Modify heat gains)………………..919-926 3.1. Shifting of dayheat to night for removal……………………………………..920-924 3.1.1. Thermal mass in the construction material…………………………..920-920 3.1.2. Thermal mass using PCM based system……………………………..920-921 3.1.2.1. PCM in wallboards……………………………………………....921-922 3.1.2.2. PCM in ceiling & roof…………………………………………...922-923 3.1.2.3. PCM in glass windows…………………………………………..924-924 3.2. Use of night coolness for day cooling ……………………………………….924-926 4. Heat dissipation technique (Remove internal heat)……………………………….926-938 4.1. Natural ventilation……………………………………………………………926-932 4.1.1. Wind driven cross ventilation………………………………………...926-927 4.1.2. Buoyancy driven stack ventilation…………………………………....927-930 4.1.3. Single sided ventilation……………………………………………….930-932 4.2. Natural cooling………………………………………………………………..932-938 4.2.1. Evaporative cooling…………………………………………………...932-932 4.2.2. Ground cooling………………………………………………………..933-936 4.2.3. -

Impact of Passive Cooling on Thermal Comfort in a Single-Family Building for Current and Future Climate Conditions

energies Article Impact of Passive Cooling on Thermal Comfort in a Single-Family Building for Current and Future Climate Conditions Krzysztof Grygierek 1,* and Izabela Sarna 2 1 Faculty of Civil Engineering, Silesian University of Technology, Akademicka 5, 44-100 Gliwice, Poland 2 Faculty of Energy and Environmental Engineering, Silesian University of Technology, Konarskiego 20, 44-100 Gliwice, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-32-237-24-97 Received: 25 September 2020; Accepted: 10 October 2020; Published: 13 October 2020 Abstract: Today, there is a great deal of emphasis on reducing energy use in buildings for both economic and environmental reasons. Investors strongly encourage the insulating of buildings. Buildings without cooling systems can lead to a deterioration in thermal comfort, even in transitional climate areas. In this article, the effectiveness of natural ventilation in a passive cooling building is analyzed. Two options are considered: cooling with external air supplied to the building by fans, or by opening windows (automatically or by residents). In both cases, fuzzy controllers for the cooling time and supply airflow control are proposed and optimized. The analysis refers to a typical Polish single-family building. Simulations are made with the use of the EnergyPlus program, and the model is validated based on indoor temperature measurement. The calculations were carried out for different climate data: standard and future (warmed) weather data. Research has shown that cooling with external air can effectively improve thermal comfort with a slight increase in heating demand. However, to be able to reach the potential of such a solution, fans should be used.