Various Methods for Measuring the Geometrical Properties of the Long

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shapebuilder 3 Properties Defined

ShapeBuilder 3.0 Geometric and Structural Properties Coordinate systems: Global (X,Y), Centroidal (x,y), Principal (1,2) Basic Symbols Units Notes: Definitions Geometric Analysis or Properties Shape Types, Area A, L2 Non-composite Gross (or full) Cross-sectional area of the shape. Also Ag shapes. A = dA ∫ A Depth d L All Total or maximum depth in the y direction from the extreme fiber at the top to the extreme fiber at the bottom. Width b, L All Total or maximum width in the x direction from the extreme fiber at the left to the extreme fiber at Also w the right. 2 Net Area An L Non-composite Net cross-sectional area, after subtracting interior holes. shapes with A = dA − A interior holes ∫ ∑ hole A Holes Perimeter p L All The sum of the external edges of the shape. Useful for calculating the surface area of a member for painting. Center of c.g., (Point) (L,L) All, unless That point where the moment of the area is zero about any axis. This point is measured from the Gravity Also located at the global XY axes. Centroid of (Xc,Yc) global origin. xdA ydA Area ∫ ∫ x = A , y = A c A c A 4 Moments of Ix, Iy, Ixy L All Second moment of the area with respect to the subscripted axis, a measure of the stiffness of the Inertia cross section and its ability to resist bending moments. I = y 2 dA, I = x 2 dA, I = xydA x ∫ y ∫ xy ∫ A A A Principal Axes 1, 2, Θ, Coordinate Any shape The axes orientation at which the maximum and minimum moments of inertia are obtained. -

Polar Moment of Inertia 2 J0 I Z R Da

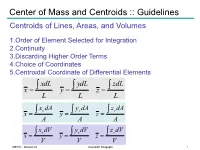

Center of Mass and Centroids :: Guidelines Centroids of Lines, Areas, and Volumes 1.Order of Element Selected for Integration 2.Continuity 3.Discarding Higher Order Terms 4.Choice of Coordinates 5.Centroidal Coordinate of Differential Elements xdL ydL zdL x y z L L L x dA y dA z dA x c y c z c A A A x dV y dV z dV x c y c z c V V V ME101 - Division III Kaustubh Dasgupta 1 Center of Mass and Centroids Theorem of Pappus: Area of Revolution - method for calculating surface area generated by revolving a plane curve about a non-intersecting axis in the plane of the curve Surface Area Area of the ring element: circumference times dL dA = 2πy dL If area is revolved Total area, A 2 ydL through an angle θ<2π θ in radians yL ydL A 2 yL or A y L y is the y-coordinate of the centroid C for the line of length L Generated area is the same as the lateral area of a right circular cylinder of length L and radius y Theorem of Pappus can also be used to determine centroid of plane curves if area created by revolving these figures @ a non-intersecting axis is known ME101 - Division III Kaustubh Dasgupta 2 Center of Mass and Centroids Theorem of Pappus: Volume of Revolution - method for calculating volume generated by revolving an area about a non-intersecting axis in the plane of the area Volume Volume of the ring element: circumference times dA dV = 2πy dA If area is revolved Total Volume, V 2 ydA through an angle θ<2π θ in radians yA ydA V 2 yA or V yA is the y-coordinate of the centroid C of the y revolved area A Generated volume is obtained by multiplying the generating area by the circumference of the circular path described by its centroid. -

Pure Torsion of Shafts: a Special Case

THEORY OF SIMPLE TORSION- When torque is applied to a uniform circular shaft ,then every section of the shaft is subjected to a state of pure shear (Fig. ), the moment of resistance developed by the shear stresses being everywhere equal to the magnitude, and opposite in sense, to the applied torque. For derivation purpose a simple theory is used to describe the behaviour of shafts subjected to torque . fig. shows hear System Set Up on an Element in the Surface of a Shaft ubjected to Torsion Resisting torque, T Applied torque T $ssumptions (%) The material is homogeneous, i.e. of uniform elastic properties throughout. (&) The material is elastic, following Hooke's law with shear stress proportional to shear strain. (*) The stress does not e+ceed the elastic limit or limit of proportionality. (,) Circular sections remain circular. (.) Cross-sections remain plane. (#his is certainly not the case with the torsion of non-circular sections.) (0) Cross-sections rotate as if rigid, i.e. every diameter rotates through the same angle. BASIC CONCEPTS 1. Torsion = Twisting 2. Rotation about longitudinal axis. 3. The e+ternal moment which causes twisting are known as Torque / twisting moment. 4. When twisting is done by a force (not a moment), then force required for torsion is normal to longitudinal axis having certain eccentricity from centroid. 5. Torque applied in non-circular section will cause 'warping'. Qualitative analysis is not in our syllabus 6. Torsion causes shear stress between circular planes. 7. Plane section remains plane during torsion. It means that if you consider the shaft to be composed to infinite circular discs. -

Shafts: Torsion Loading and Deformation

Third Edition LECTURE SHAFTS: TORSION LOADING AND DEFORMATION • A. J. Clark School of Engineering •Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering 6 by Dr. Ibrahim A. Assakkaf SPRING 2003 Chapter ENES 220 – Mechanics of Materials 3.1 - 3.5 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering University of Maryland, College Park LECTURE 6. SHAFTS: TORSION LOADING AND DEFORMATION (3.1 – 3.5) Slide No. 1 Torsion Loading ENES 220 ©Assakkaf Introduction – Members subjected to axial loads were discussed previously. – The procedure for deriving load- deformation relationship for axially loaded members was also illustrated. – This chapter will present a similar treatment of members subjected to torsion by loads that to twist the members about their longitudinal centroidal axes. 1 LECTURE 6. SHAFTS: TORSION LOADING AND DEFORMATION (3.1 – 3.5) Slide No. 2 Torsion Loading ENES 220 ©Assakkaf Torsional Loads on Circular Shafts • Interested in stresses and strains of circular shafts subjected to twisting couples or torques • Turbine exerts torque T on the shaft • Shaft transmits the torque to the generator • Generator creates an equal and opposite torque T’ LECTURE 6. SHAFTS: TORSION LOADING AND DEFORMATION (3.1 – 3.5) Slide No. 3 Torsion Loading ENES 220 ©Assakkaf Net Torque Due to Internal Stresses • Net of the internal shearing stresses is an internal torque, equal and opposite to the applied torque, T = ∫∫ρ dF = ρ(τ dA) • Although the net torque due to the shearing stresses is known, the distribution of the stresses is not • Distribution of shearing stresses is statically indeterminate – must consider shaft deformations • Unlike the normal stress due to axial loads, the distribution of shearing stresses due to torsional loads can not be assumed uniform. -

Problem Set #8 Solution 1.050 Solid Mechanics Fall 2004

Problem Set #8 Solution 1.050 Solid Mechanics Fall 2004 Problem 8.1 A solid aluminum, circular shaft has length 0.35 m and diameter 6 mm. How much does one end rotate relative to the other if a torque about the shaft axis of 10 N-m is applied? GJ We turn to the stiffness relationship, M = ------- φ⋅ in order to determine the relative angle of twist, t L φ, over the length of the shaft, L. For a solid circular shaft, the moment of inertia, J= πR4/2. The shear mod- E ulus G is related to the material’s elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio by G = -------------------- and the elastic mod 21( + ν) ulus for Aluminum, found in the table on page 212 is 70 E 09 N/m2. Taking Poisson’s ratio as 1/3, G then evaluates to 26 E 09 N/m2. Putting all of this together gives φ L ⋅ an angle of rotation = ------- Mt = 1.06 radians . The maximum shear stress is obtained from τ ⁄ GJ max = MtRJ. τ × 08 2 This evaluates to max = 2.36 10 N/m (This is the change 12 Nov. 04). *** What follows is an excursion which considers the possibility of plastic flow in the shaft. We see that the maximum shear stress is near or greater than τ one-half the yield stress (in tension) of the three types of Aluminum τ given in the table in chapter 7. So what will ensue? y To proceed, we need a model for the constitutive behavior that G includes the relationship between shear stress and shear strain beyond the elastic range. -

DESIGN and SIMULATION of TORSION BAR(ARB) for FSAE USING MATLAB Parimala Pavan Jonnada Dr

International Journal of Engineering Applied Sciences and Technology, 2020 Vol. 5, Issue 8, ISSN No. 2455-2143, Pages 278-281 Published Online December 2020 in IJEAST (http://www.ijeast.com) DESIGN AND SIMULATION OF TORSION BAR(ARB) FOR FSAE USING MATLAB Parimala Pavan Jonnada Dr. Sreekanth Dondapati B.Tech Mechanical Engineering, School of Head of Department, School of Mechanical Mechanical Engineering, Vellore Institute of Engineering, Vellore Institute of Technology, Technology, Chennai, India – 600127 Chennai, India – 600127 Abstract - Formula SAE is a student design wheels can return to their normal height against the competition organized by SAE vehicle, kept at similar levels by the connecting International (previously known as the Society of sway bar. Automotive Engineers, SAE). The concept Because each pair of wheels is cross-connected by a behind Formula SAE is that a fictional bar, the combined operation causes all wheels to manufacturing company has contracted a generally offset the separate tilting of the others and student design team to develop a small Formula- the vehicle tends to remain level against the general style race car. The prototype race car is to be slope of the terrain. evaluated for its potential as a production item. Each student team designs, builds and tests a Anti-roll bars provide two main functions. The first prototype based on a series of rules, whose function is the reduction of body lean. The reduction purpose is both ensuring on-track safety and of body lean is dependent on the total roll stiffness promoting clever problem solving. An anti-roll of the vehicle. Increasing the total roll stiffness of a bar is a part of automobile suspensions that helps vehicle does not change the steady state total load reduce the body roll of a vehicle during fast transfer from the inside wheels to the outside cornering or over road irregularities. -

Numerical Analysis and Demonstration: Transmission Shaft Influence on Meshing Vibration in Driving and Driven Gears

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Shock and Vibration Volume 2015, Article ID 365084, 10 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/365084 Research Article Numerical Analysis and Demonstration: Transmission Shaft Influence on Meshing Vibration in Driving and Driven Gears Xu Jinli, Su Xingyi, and Peng Bo Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan 430070, China Correspondence should be addressed to Su Xingyi; [email protected] Received 23 November 2014; Accepted 3 April 2015 Academic Editor: Wen Long Li Copyright © 2015 Xu Jinli et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The variable axial transmission system composed of universal joint transmission shafts and a gear pair has been applied inmany engineering fields. In the design of a drive system, the dynamics of the gear pair have been studied in detail. However fewhave paid attention to the effect on the system modal characteristics of the gear pair, arising from the universal joint transmission shafts. This work establishes a torsional vibration mathematical model of the transmission shaft, driving gear, and driven gear based on lumped masses and the main reducer system assembly of a CDV (car-based delivery vehicle) car. The model is solved by the state space method. The influence of the angle between transmission shafts and intermediate support stiffness on the vibration and noise of the main reducer is obtained and verified experimentally. A reference for the main reducer and transmission shaft design and the allied parameter matching are provided. -

Statics - TAM 211

Statics - TAM 211 Lecture 32 April 9, 2018 Chap 10.1, 10.2, 10.4, 10.8 Announcements No class Wednesday April 11 No office hours for Prof. H-W on Wednesday April 11 Upcoming deadlines: Tuesday (4/10) PL HW 12 Thursday (4/12) WA 5 due Monday (4/16) Mastering Engineering Tutorial 14 Chapter 10: Moments of Inertia Goals and Objectives • Understand the term “moment” as used in this chapter • Determine and know the differences between • First/second moment of area • Moment of inertia for an area • Polar moment of inertia • Mass moment of inertia • Introduce the parallel-axis theorem. • Be able to compute the moments of inertia of composite areas. Applications Many structural members like beams and columns have cross sectional shapes like an I, H, C, etc.. Why do they usually not have solid rectangular, square, or circular cross sectional areas? What primary property of these members influences design decisions? Applications Many structural members are made of tubes rather than solid squares or rounds. Why? This section of the book covers some parameters of the cross sectional area that influence the designer’s selection. Recap: First moment of an area (centroid of an area) The first moment of the area A with respect to the x-axis is given by The first moment of the area A with respect to the y-axis is given by The centroid of the area A is defined as the point C of coordinates and , which satisfies the relation In the case of a composite area, we divide the area A into parts , , Terminology: the term moment in this module refers to the mathematical sense of different “measures” of an area or volume. -

153 Chapter 8

Chapter 8 - Area Moments of Inertia Reading: Chapter 8 - Pages 297 – 313 8-1 Introduction Area Moment of Inertia The second moment of area is also known as the moment of inertia of a shape. The second moment of area is a measure of the "efficiency" of a cross-sectional shape to resist bending caused by loading. The Symbol for Moment of Inertia is I The units of moment of inertia are length raised to the fourth power, such as, in4 or mm4 Moments of inertia of areas are used in calculating the stresses and deflections of beams, the torsion of shafts, and the buckling of columns. The location of the centroid of an area involves the quantity ΣxΔA, which represents the first moment of the area. The area moment of inertia involves the quantity Σx2ΔA, which represent the second moment of an area (because x is squared). The moment of inertia is always computed with respect to an axis; its value is greatly affected by the distribution of the area relative to the axis. Both beams have the same area and even the same shape. Beam 1 is stronger than Beam 2 because it has a larger second moment of inertia (I). Orientation can change the second moment of area (I). For a rectangle, where b is the breadth (horizontal) and h is the height (vertical) if the load is vertical i.e. gravity load If Beam 1 and Beam 2 are 2 in x 12 in, Beam 1 h=12 in Ix = 1/12 (2 in)(12in)3 = 288 in4 X X b =2 in Beam 2 X X h=2 in Ix = 1/12 (12 in)(2in)3 = 8 in4 b =12 in Under the same loading conditions, Beam 2 will bend before Beam 1. -

Torsiontorsion

MechanicsMechanics && MaterialsMaterials 11 ChapterChapter 1111 TorsionTorsion FAMU-FSU College of Engineering Department of Mechanical Engineering TorsionTorsion • Torsion refers to the twisting of a structural member when it is loaded by couples that produce rotation about the longitudinal axis • The couples that cause the tension are called Torques, Twisting Couples or Twisting Moments TorsionTorsion ofof CircularCircular BarBar • From consideration of symmetry: – Cross sections of the circular bar rotates as rigid bodies about the longitudinal axis – Cross sections remain straight and circular TorsionTorsion ofof CircularCircular BarsBars • If the right hand of the bar rotates through a small angle φ – φ: angle of twist • Line will rotate to a new position • The element ABCD after applying torque b → b′ → Element in state of “pure d → d′ shear” ShearShear StrainStrain • During torsion, the right-hand cross section of the original configuration of the element (abdc) rotates with respect to the opposite face and points b and c move to b' and c'. • The lengths of the sides of the element do not change during this rotation, but the angles at the corners are no longer 90°. Thus, the element is undergoing pure shear and the magnitude of the shear strain is equal to the decrease in the angle bab'. This angle is bb′ tan γ = ab ShearShear StrainStrain γγ tan γ ≈ γ because under pure torsion the angle γ is small. So ′ φ γ = bb = rd ab dx Under pure torsion, the rate of change dφ/dx of the angle of twist is constant along the length of the bar. This constant is equal to the angle of twist per unit length θ. -

Bending Strength of Materials

274.pdf A SunCam online continuing education course What Every Engineer Should Know About Structures Part D - Bending Strength Of Materials by Professor Patrick L. Glon, P.E. 274.pdf What Every Engineer Should Know About Structures - Part D - Bending Strength of Materials A SunCam online continuing education course This is a continuation of a series of courses in the area of study of physics called engineering mechanics. This is a series of courses in Statics and Strength of Materials. This is the fourth course of the series and is called What Every Engineer Should Know About Structures - Part D - Bending Strength of Materials. The study of Strength of Materials takes the step after Statics and focuses on solving problems dealing with the stresses within those members of a stationary body (beams, columns, cables, etc.). This series will provide the tools for solving some of the most common structural design and analysis problems. The focus will be on presenting simplified methods of solving problems. This course includes: • cross sectional properties of structural members including defining and determining the Moment of Inertia and Section Modulus of a cross section. • torsional stresses and deformations of rods and shafts • shear and bending moment diagrams of beams • bending stresses in loaded beams • shear stresses in loaded beams This course is a continuation of the previous course What Every Engineer Should Know About Structures - Part C - Axial Strength of Materials. You should be familiar with the information presented in that course before proceeding with this course. www.SunCam.com Copyright 2017 Professor Patrick L. Glon, P.E. -

UNIT III TORSION Torsion Formulation Stresses and Deformation in Circular

UNIT III TORSION Torsion formulation stresses and deformation in circular and hollows shafts – Stepped shafts– Deflection in shafts fixed at the both ends – Stresses in helical springs – Deflection of helical springs, carriage springs. Torsion of circular shafts Definition of Torsion: Consider a shaft rigidly clamped at one end and twisted at the other end by a torque T = F.d applied in a plane perpendicular to the axis of the bar such a shaft is said to be in torsion. Effects of Torsion: The effects of a torsional load applied to a bar are (i) To impart an angular displacement of one end cross � section with respect to the other end. (ii) To setup shear stresses on any cross section of the bar perpendicular to its axis. GENERATION OF SHEAR STRESSES The physical understanding of the phenomena of setting up of shear stresses in a shaft subjected to a torsion may be understood from the figure 1-3. Fig 1: Here the cylindrical member or a shaft is in static equilibrium where T is the resultant external torque acting on the member. Let the member be imagined to be cut by some imaginary plane �mn'. Fig 2: When the plane �mn' cuts remove the portion on R.H.S. and we get a fig 2. Now since the entire member is in equilibrium, therefore, each portion must be in equilibrium. Thus, the member is in equilibrium under the action of resultant external torque T and developed resisting Torque Tr . Fig 3: The Figure shows that how the resisting torque Tr is developed.