The Geographical Structure of Capitalism at the Origin of Cultural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landesrekorde Marathon Welt

Landesrekorde Stand: 20.12.2020 Landesrekorde Marathon der Männer Landesrekorde Marathon der Frauen Pl. Land Zeit Diff. Name Jahr Ort Pl. Land Zeit Diff. Name Jahr Ort 1. Kenia 2:01:39 Eliud Kipchoge 2018 Berlin 1. Kenia 2:14:04 Brigid Kosgei 2019 Chicago 2. Äthiopien 2:01:41 (0:00:02) Kenenisa Bekele 2019 Berlin 2. Großbritanien 2:15:25 (0:01:21) Paula Radcliffe 2003 London 3. Türkei 2:04:16 (0:02:37) Kaan Kigen Özbilen 2019 Valencia 3. Äthiopien 2:17:41 (0:03:37) Degefa Workneh 2019 Dubai 4. Bahrain 2:04:43 (0:03:04) El Hassan el-Abbassi 2018 Valencia 4. Israel 2:17:45 (0:03:41) Lonah Chematai Salpeter 2020 Tokio 5. Belgien 2:04:49 (0:03:10) Bashir Abdi 2020 Tokio 5. Japan 2:19:12 (0:05:08) Mizuki Noguchi 2005 Berlin 6. England 2:05:11 (0:03:32) Mo Farah 2018 Chicago 6. Deutschland 2:19:19 (0:05:15) Irina Mikitenko 2008 Berlin 7. Großbritanien 2:05:11 (0:03:32) Mo Farah 2018 Chicago 7. USA 2:19:36 (0:05:32) Deena Kastor 2006 London 8. Uganda 2:05:12 (0:03:33) Felix Chemonges 2019 Toronto 8. China 2:19:39 (0:05:35) Yingjie Sun 2003 Beijing 9. Marokko 2:05:26 (0:03:47) El Mahjoub Dazza 2018 Valencia 9. Namibia 2:19:52 (0:05:48) Helalia Johannes 2020 Valencia 10. Japan 2:05:29 (0:03:50) Suguru Osako 2020 Tokio 10. Rußland 2:20:47 (0:06:43) Galina Bogomolova 2006 Chicago 11. -

IMPRESSIONEN IMPRESSIONS Bmw-Berlin-Marathon.Com

IMPRESSIONEN IMPRESSIONS bmw-berlin-marathon.com 2:01:39 DIE ZUKUNFT IST JETZT. DER BMW i3s. BMW i3s (94 Ah) mit reinem Elektroantrieb BMW eDrive: Stromverbrauch in kWh/100 km (kombiniert): 14,3; CO2-Emissionen in g/km (kombiniert): 0; Kraftstoffverbrauch in l/100 km (kombiniert): 0. Die offi ziellen Angaben zu Kraftstoffverbrauch, CO2-Emissionen und Stromverbrauch wurden nach dem vorgeschriebenen Messverfahren VO (EU) 715/2007 in der jeweils geltenden Fassung ermittelt. Bei Freude am Fahren diesem Fahrzeug können für die Bemessung von Steuern und anderen fahrzeugbezogenen Abgaben, die (auch) auf den CO2-Ausstoß abstellen, andere als die hier angegebenen Werte gelten. Abbildung zeigt Sonderausstattungen. 7617 BMW i3s Sportmarketing AZ 420x297 Ergebnisheft 20180916.indd Alle Seiten 18.07.18 15:37 DIE ZUKUNFT IST JETZT. DER BMW i3s. BMW i3s (94 Ah) mit reinem Elektroantrieb BMW eDrive: Stromverbrauch in kWh/100 km (kombiniert): 14,3; CO2-Emissionen in g/km (kombiniert): 0; Kraftstoffverbrauch in l/100 km (kombiniert): 0. Die offi ziellen Angaben zu Kraftstoffverbrauch, CO2-Emissionen und Stromverbrauch wurden nach dem vorgeschriebenen Messverfahren VO (EU) 715/2007 in der jeweils geltenden Fassung ermittelt. Bei Freude am Fahren diesem Fahrzeug können für die Bemessung von Steuern und anderen fahrzeugbezogenen Abgaben, die (auch) auf den CO2-Ausstoß abstellen, andere als die hier angegebenen Werte gelten. Abbildung zeigt Sonderausstattungen. 7617 BMW i3s Sportmarketing AZ 420x297 Ergebnisheft 20180916.indd Alle Seiten 18.07.18 15:37 AOK Nordost. Beim Sport dabei. Nutzen Sie Ihre individuellen Vorteile: Bis zu 385 Euro für Fitness, Sport und Vorsorge. Bis zu 150 Euro für eine sportmedizinische Untersuchung. -

Identity and Diversity: What Shaped Polish Narratives Under Communism and Capitalism Witold Morawski1

„Journal of Management and Business Administration. Central Europe” Vol. 25, No. 4/2017, p. 209–243, ISSN 2450-7814; e-ISSN 2450-8829 © 2017 Author. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/) Identity and Diversity: What Shaped Polish Narratives Under Communism and Capitalism Witold Morawski1 at first, the motherland is close at your fingertips later it bleeds hurts – Tadeusz Różewicz (1999, p. 273) Aims I shall refer to concepts of identity and difference on the border between culture and society not only to better understand and explain waves of social anger experienced by individuals or communities but also to reflect on ways in which to address the challenges that emerge within the social environment. One is angry when struggling with financial insecurity due to unemployment or low income; economists analyse this phenomenon. Another one is angry because of the mediocrity of those in power; political scientists explore this matter. The media, whose task is to bring the above to public attention, also become instruments that shape events and they aspire or even engage in exercising power. Thus, I shift the focus to society and its culture as sources of anger and, at the same time, areas where we may appease anger (Mishra, 2017; Sloterdijk, 2011). People often tap into the power of identity and difference as a resource. I do not assume that culture prevails, but society needs to take it into account if it is to understand itself and change any distressing aspects of reality. -

ÖBKT Deell .RAAD VAN BEHEER .RADIO .TELEVISE

ÖBKT JAAROVERZICHT 1987 DEELl .RAAD VAN BEHEER .RADIO .TELEVISE Jaaroverzicht 1987. TEN GELEIDE In 1987 heeft de BRT voor zichzelf duidelijk willen uitmaken wat de taak van de openbare omroep in Vlaanderen voor de ko mende jaren moet zijn, en wat er nodig is om in vergelijking met vergelijkbare omroepen uit het vergelijkbare buitenland een behoorlijk figuur te slaan. Daarvoor werden realistisch geachte vijfjarenplannen opgesteld. De BRT bereidde zich op de uitdaging van de toekomst voor. Uitgaande van de meest gangbare filosofie terzake en zich gesteund voelend door krachtdadige uitspraken van gezagheb bende instanties die een goed functionerende en adequaat ge financierde openbare omroep als een conditio sine qua non voor grondige wijzigingen in het mediabestel beschouwen, heeft de BRT gemeend te moeten stellen dat een fatsoenlijke invulling van zijn informerende, vormende en ontspannende opdracht een minimaal bedrag van 7,5 miljard Bfr. vereist, wat toevallig overeenkomt met 75 % van het momenteel in Vlaanderen geïnde kijk- en luistergeld. In 1987 kreeg de BRT daar 52 % van. (Ter illustratie : de Deense omroep DR, werkend voor een bevolking die ongeveer even groot is als de Vlaamse, maar met bijna 1000 tv-uren en 10.000 radio-uren minder dan de BRT, beschikte over bijna tweemaal het inkomen van de BRT). De Nederlandse omroep heeft een budget van ingeveer 20 miljard frank; de BRT beschikt over 5,4 miljard om ook twee tv- netten en vijf radionetten te vullen. Toch is de BRT er jaar na jaar in geslaagd zonder deficit te eindigen. Het budget werd met uiterste zorg beheerd. Van de Doorlichting, die gevraagd was om na te gaan of de BRT zijn mensen en middelen wel efficiënt genoeg gebruikt, werd het eindrapport in maart 1987 ingediend. -

Report of the Electoral Observation Mission

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN MEXICO JUNE 7TH 2015 REPORT OF THE ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION Parliamentary Confederation of the Americas TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. TERMS OF REFERENCE OF THE MISSION............................................................................................................................ 5 2. COMPOSITION OF THE DELEGATION .................................................................................................................................... 7 TABLE 2.1: PARLIAMENTARIANS WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE MISSION ........................................................... 7 3. MISSION ACTIVITIES BEFORE ELECTION DAY.................................................................................................................. 9 3.1 Arrival of delegation and accreditation of members .............................................................................................. 9 3.2 Working meetings with representatives of institutions and organizations involved in the electoral process ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 3.2.1 Openings session of the program for international visitors ................................................................... 10 3.2.2 Working meeting -

Cardiff 2016 F&F

IAAF/Cardiff University WORLD HALF MARATHON CHAMPIONSHIPS FACTS & FIGURES Incorporating the IAAF World Half Marathon Championships (1992-2005/2008-2010-2012-2014) IAAF World Road Running Championships 2006/2007 Past Championships...............................................................................................1 Past Medallists .......................................................................................................1 Overall Placing Table..............................................................................................5 Most Medals Won...................................................................................................6 Youngest & Oldest..................................................................................................7 Most Appearances by athlete.................................................................................7 Most Appearances by country................................................................................8 Country Index .......................................................................................................10 World Road Race Records & Best Performances at 15Km, 20Km & Half Mar .........39 Progression of World Record & Best Performance at 15Km, 20Km & Half Mar .......41 CARDIFF 2016 ★ FACTS & FIGURES/PAST CHAMPS & MEDALLISTS 1 PAST CHAMPIONSHIPS –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– These totals do not include athletes entered for the championships who never started, but teams are counted -

African Studies Abstracts Online: Number 25, 2009 Boin, M.; Polman, K.; Sommeling, C.M.; Doorn, M.C.A

African Studies Abstracts Online: number 25, 2009 Boin, M.; Polman, K.; Sommeling, C.M.; Doorn, M.C.A. van Citation Boin, M., Polman, K., Sommeling, C. M., & Doorn, M. C. A. van. (2009). African Studies Abstracts Online: number 25, 2009. Leiden: African Studies Centre. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13427 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13427 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Number 25, 2009 AFRICAN STUDIES ABSTRACTS ONLINE Number 25, 2009 Contents Editorial policy............................................................................................................... iii Geographical index ....................................................................................................... 1 Subject index................................................................................................................. 3 Author index.................................................................................................................. 7 Periodicals abstracted in this issue............................................................................... 14 Abstracts ....................................................................................................................... 18 Abstracts produced by Michèle Boin, Katrien Polman, Tineke Sommeling, Marlene C.A. Van Doorn ii EDITORIAL POLICY African Studies Abstracts Online provides an overview of articles -

Journal on Education in Emergencies

JOURNAL ON EDUCATION IN EMERGENCIES The Potential of Conflict-Sensitive Education Approaches in Fragile Countries: The Case of Curriculum Framework Reform and Youth Civic Participation in Somalia Author(s): Marleen Renders and Neven Knezevic Source: Journal on Education in Emergencies¸ Vol 3, No 1 (July 2017), pp 106 - 128 Published by: Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies Stable URL: http://hdl.handle.net/2451/39661 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17609/N8X087 REFERENCES: This is an open-source publication. Distribution is free of charge. All credit must be given to authors as follows: Renders, Marleen and Neven Knezevic. 2017. The Potential of Conflict-Sensitive Education Approaches in Fragile Countries: The Case of Curriculum Framework Reform and Youth Civic Participation in Somalia.” Journal on Education in Emergencies 3(1): 106 - 128. The Journal on Education in Emergencies (JEiE) publishes groundbreaking and outstanding scholarly and practitioner work on education in emergencies (EiE), defined broadly as quality learning opportunities for all ages in situations of crisis, including early childhood development, primary, secondary, non-formal, technical, vocation, higher and adult education. Copyright © 2017, Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies. The Journal on Education in Emergencies published by the Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. THE POTENTIAL OF CONFLICT-SENSITIVE EDUCATION APPROACHES IN FRAGILE COUNTRIES: THE CASE OF CURRICULUM FRAMEWORK REFORM AND YOUTH CIVIC PARTICIPATION IN SOMALIA Marleen Renders and Neven Knezevic Education is a basic human right, as well as a precondition for peace, prosperity and justice to return to Somali citizens on a lasting basis. -

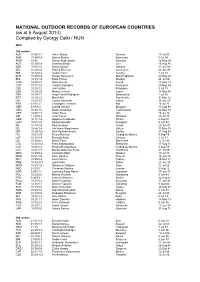

(As at 6 August 2014) Compiled by György Csiki / HUN

NATIONAL OUTDOOR RECORDS OF EUROPEAN COUNTRIES (as at 6 August 2014) Compiled by György Csiki / HUN MEN 100 metres: ALB 10.56/1.1 Arben Makaj Donnas 15 Jul 03 AND 10.94/0.9 Esteve Martin Barcelona 5 Jul 00 ARM 10.45 Arman Andreasyan Artashat 16 May 09 AUT 10.15/0.9 Andreas Berger Linz 15 Aug 88 AZE 10.08/1.3 Ramil Guliyev Istanbul 13 Jun 09 BEL 10.14/1.0 Patrick Stevens Oordegem 28 Jun 97 BIH 10.42/0.2 Nedim Covic Velenje 1 Jul 10 BLR 10.27/0.9 Sergey Kornelyuk Biala Podlaska 28 May 94 BUL 10.13/1.4 Petar Petrov Moskva 24 Jul 80 CRO 10.20/1.5 Dario Horvat Azusa 11 May 13 CYP 10.11/1.5 Yiannis Zisimides Rethymno 25 May 96 CZE 10.23/1.0 Jan Veleba Pardubice 3 Jul 10 DEN 10.29/2.0 Morten Jensen Greve 18 Sep 04 ESP 10.14/1.7 Angel David Rodriguez Salamanca 2 Jul 08 EST 10.19/1.5 Marek Niit Fayetteville 31 Mar 12 FIN 10.21/0.5 Tommi Hartonen Vaasa 23 Jun 01 FRA 9.92/2.0 Christophe Lemaitre Albi 29 Jul 11 GBR 9.87/0.3 Linford Christie Stuttgart 15 Aug 93 GEO 10.35/1.5 Besik Gotsiridze Tsakhkadzor 22 May 87 GER 10.05/1.8 Julian Reus Ulm 26 Jul 14 GIB 11.27/0.2 Jerai Torres Hamilton 15 Jul 13 GRE 10.11/1.4 Aggelos Pavlakakis Athína 2 Aug 97 HUN 10.08/1.0 Roland Németh Budapest 9 Jun 99 IRL 10.18/1.9 Paul Hession Vaasa 23 Jun 07 ISL 10.56/1.4 Jón Arnar Magnússon Götzis 31 May 97 ISR 10.20/-0.6 Alex Porkhomovskiy Sevilla 21 Aug 99 ITA 10.01/0.9 Pietro Mennea Ciudad de México 4 Sep 79 LAT 10.18/1.4 Ronalds Arajs Donnas 3 Jul 11 LIE 10.53/0.6 Martin Frick Bellinzona 12 Jul 96 LTU 10.14/-0.2 Rytis Sakalauskas Shenzhen 17 Aug 11 LUX 10.41/0.2 Roland -

Parties of Power and the Success of the President's Reform Agenda In

10.1177/003232902237826POLITICSREGINA SMYTH & SOCIETY Building State Capacity from the Inside Out: Parties of Power and the Success of the President’s Reform Agenda in Russia REGINA SMYTH In contrast to his predecessor Boris Yeltsin, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin con- tinues to successfully neutralize legislative opposition and push his reform agenda through the State Duma. His success is due in large part to the transformation of the party system during the 1999 electoral cycle. In the face of a less polarized and frag- mented party system, the Kremlin-backed party of power,Unity, became the founda- tion for a stable majority coalition in parliament and a weapon in the political battle to eliminate threatening opponents such as Yuri Luzhkov’s Fatherland–All Russia and the Communist Party of the Russian Federation. Political transitions under presidential regimes are prone to deadlock between the parliament and the executive that can stymie reform efforts and even lead to a breakdown in nascent democracies.1 I argue that a centrist state party (an organi- zation formed by state actors to mobilize budgetary resources to contest parlia- mentary elections) operating within a nonpolarized party system can serve as a mechanism to overcome parliamentary-presidential deadlock. I support this argu- ment using data on the electoral strategies and governing success of the first three post-Communist administrations in the Russian Federation. In doing so, this study underscores how a mixed electoral system (i.e., deputies simultaneously Funding for this work was provided by the National Science Foundation and the National Council for Eurasian Studies. This article greatly benefited from comments from Pauline Jones Luong, Anna Gryzmala-Busse, Timothy Colton, Thomas Remington, Philip Roeder, William Bianco, Julie Corwin, and Lee Carpenter. -

2014 European Championships Statistics – Women's 100M

2014 European Championships Statistics – Women’s 100m by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the European Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 10.73 2.0 Christine Arron FRA 1 Budapest 1998 2 10.81 1.3 Christine Arron 1sf1 Budapest 1998 3 2 10.83 2.0 Irina Privalova RUS 2 Budapest 1998 4 3 10.87 2.0 Ekaterini Thanou GRE 3 Budapest 1998 5 4 10.89 1.8 Katrin Krabbe GDR 1 Split 1990 6 5 10.91 0.8 Marlies Göhr GDR 1 Stuttgart 1986 7 10.92 0.9 Ekaterini Thanou 1sf2 Budapest 1998 7 6 10.92 2.0 Zhanna Pintusevich -Block UKR 4 Budapest 1998 9 10.98 1.2 Marlies Göhr 1sf2 Stuttgart 1986 10 11.00 1.3 Zhanna Pintusevich -Block 2sf1 Budapest 1998 11 11.01 -0.5 Marlies Göhr 1 Athinai 1982 11 11.01 0.9 Zhanna Pintusevich -Block 1h2 Helsinki 1994 13 11.02 0.6 Irina Privalova 1 Helsinki 1994 13 11.02 0.9 Irina Privalova 2sf2 Budapest 1998 15 7 11.04 0.8 Anelia Nuneva BUL 2 Stuttgart 1986 15 11.04 0.6 Ekaterini Thanou 1h4 Budapest 1998 17 8 11.05 1.2 Silke Gladisch -Möller GDR 2sf2 Stuttgart 1986 17 11.05 0.3 Ekaterini Thanou 1sf2 München 2002 19 11.06 -0.1 Marlies Göhr 1h2 Stuttgart 1986 19 11.06 -0.8 Zhanna Pintusevich -Block 1h1 Budapest 1998 19 9 11.06 1.8 Kim Gevaert BEL 1 Göteborg 2006 22 10 11.06 1.7 Ivet Lalova BUL 1h2 Helsinki 2012 22 11.07 0.0 Katrin Krabbe 1h1 Split 1990 22 11 11.07 2.0 Melanie Paschke GER 5 Budapest 1998 25 11.07 0.3 Ekaterini Thanou 1h4 München 2002 25 11.08 1.2 Anelia Nuneva 3sf2 Stuttga rt 1986 27 12 11.08 0.8 Nelli Cooman NED 3 Stuttgart 1986 28 11.09 0.8 Silke Gladisch -Möller -

The Time of Buen Vivir in Chile: Power Returns to Its Legitimate Owners

The time of Buen Vivir in Chile: power returns to its legitimate owners The results of Chile’s elections for the Constitutional Convention marked a breaking point in the country’s history. At the same time as the particracy is demolished and the political class defeated, the epicenter of decision-making finds its way back to the people. Right now, indigenous and Chilean men and women must unite to reach Kume Mongen, and thus allow for a diverse coexistence under conditions of greater equity and an unconditional respect for Mother Earth. By Diego Ancalao Gavilán - 1st of June, 2021 After the social outburst of 2019, many remained in a state of total shock. The traditional political system believed, under a sort of infantile ingenuity, that this would only amount to a bad dream, and that sooner rather than later, they would gain back control over a space that they felt belonged to them by right. However, events have unfolded under a stubborn consistency, and the codes that allowed for an anticipatory interpretation of events are no longer functioning. The facts have placed the political class, which was until now dominant, in the place that they have earned themselves with merit: that of complete irrelevance. As Pope Francis reminds us in his apostolic exhortation, Evangelio Gaudium, under the current times, one must assume that to have an impact on the adequate development of social coexistence, and on the building of a people in which differences are harmonized by a common project, one must understand that “reality is superior to the idea”.