Bird Observer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

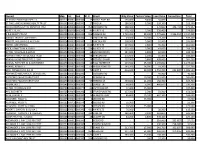

2018 Property Assessment Data

Owner1 Map Lot Sub St. # Street Bldg Value Feature Value Land Value Current Use Total 17 STONE POST ROAD SPE LLC 000210 000014 000000 17 STONE POST RD 196,800 9,400 54,800 - 261,000 27 PINE LANE NOMINEE REALTY TRUST 000240 000018 000000 27 PINE LN 180,500 8,900 339,100 - 528,500 359 COXBOROUGH RD NOMINEE TRST 000250 000008 000000 359 COXBORO RD 180,500 - 279,600 184,733 275,367 40 RT 113, LLC 000236 000108 000000 40 NH RT 113 176,200 3,200 350,400 - 529,800 A & B REALTY TRUST 000231 000013 000000 106 PAUGUS RD 1,733,300 88,100 4,479,600 2,986,192 3,314,808 ABBIATI TRUSTEE, ANTHONY J. 000235 000009 000000 71 FINISTERE RD 49,000 10,500 779,700 - 839,200 ABBOTT, WILLIAM G & ALICIA M 000224 000007 000000 21 LINCOLN RD 268,900 5,000 62,900 - 336,800 ABEAR, JONATHAN D. 000212 000011 000000 1118 NH RT 175 114,500 2,300 46,100 - 162,900 ABER, KENNETH M & EMILY 000227 000032 000001 738 NH RT 175 352,100 3,000 43,600 - 398,700 ACTON, NICHOLAS & BONNI 000245 000023 000000 33 WILDWOOD DR 284,000 3,800 50,900 - 338,700 ADAMS FAMILY REVOCABLE TRUST 000227 000046 000000 98 SARGENT RD 274,600 2,500 56,300 - 333,400 ADAMS LIVING TRUST DEC 5 1991 000235 000007 000000 28 POTATO ISLAND 137,900 5,800 438,000 - 581,700 ADAMS, FLETCHER W & ADRIENNE E 000241 000007 000000 10 TALL TIMBER DR 119,500 15,900 1,139,600 - 1,275,000 ADAMS, ROBERT S 000229 000022 000000 66 PERCH POND RD 149,200 14,300 59,200 - 222,700 ADIE, DONALD M & JILL M 000244 000013 000000 76 US RT 3 416,600 39,500 1,752,700 222,280 1,986,520 ADVANCED MECHANICAL DEVICES INC 000250 000033 000000 COXBORO RD - - 40,300 - 40,300 AGOSTINO PALMIERI IRR TRUST 000240 000035 000000 PERKINS LN - 19,500 321,500 - 341,000 AGOSTINO PALMIERI IRR TRUST 000240 000009 000000 59 PERKINS LN 459,800 21,200 158,400 - 639,400 AHERN, INA J. -

New Hampshire Fish Consumption Guidelines

ARD-EHP-25 2020 New Hampshire Fish Consumption Guidelines Fish and shellfish are an important part of a healthy diet. They are a good source of low fat protein and contain nutrients like omega-3 fatty acids, a key nutrient for brain development. NHDES offers these fish consumption guidelines to educate the public regarding certain contaminants that have been analyzed in fish tissues. There are other contaminants that may be present in the environment that have not been analyzed, nor are they included in this advisory. Mercury analysis has been completed for a variety of the most common freshwater fish species, however not all species or waterbodies have been analyzed for mercury and the other contaminants listed in the advisory (fish sampled to date include 26 species, >230 waterbodies, ~4,000 fish). Mercury does not break down in the environment. Nearly all fish and shellfish have traces of mercury, and fish from some freshwater sources may also contain polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) or dioxin. Small amounts of mercury can damage a brain starting to form or grow. That is why babies and young children are at most risk. PCBs and dioxins are man-made organic chemicals which do not readily break down in the environment. They are taken up and may accumulate in fish. PCBs and dioxins have been shown to cause a variety of harmful health effects such as cancer as well as non-cancer health effects involving immune, reproductive, nervous and endocrine systems. Risks from mercury, PCBs and dioxin in fish and shellfish depend on the amount of fish and shellfish eaten and the levels of these contaminants in the fish and shellfish. -

Hazard Mitigation Plan Update, 2015

Town of Holderness, New Hampshire Hazard Mitigation Plan Update, 2015 Prepared by the: Holderness Hazard Mitigation Update Committee Pemigewasset River flooding in Holderness along NH Rte. 175, April 2011 Credit: http://farm7.staticflickr.com/6079/6092948164_57ea16a060_z.jpg January 2015 Intentionally left blank. Town of Holderness, New Hampshire Hazard Mitigation Plan Update January 2015 With Assistance from: Lakes Region Planning Commission 103 Main Street, Suite #3 Meredith, NH 03253 Phone: (603) 279-8171 Fax: (603) 279-0200 www.lakesrpc.org Funding for this plan was provided by the NH Department of Safety, Homeland Security and Emergency Management, and with matching funds provided by the Lakes Region Planning Commission. THE LAKES REGION PLANNING COMMISSION Tamworth Sandwich Freedom Holderness Effingham A Moultonborough s h Ossipee la n d or r b Tuftonboro Hebron r e ar te t H a en w e C g d ri B n Meredith to Alexandria p Bristol m a H W olfeboro w e N Laconia Gilford Danbury Hill Sanbornton Alton F r a Tilton Belmont n k l Andover i n Gilmanton Northfield Barnstead LRPC COMMISSIONERS 2013-2014 Alexandria Belmont Effingham Hebron Moultonborough Sandwich Janet Towse Vacant Theresa Swanick Mitch Manseau Herbert Farnham Toby Eaton Barbara Perry Alton Bridgewater Franklin Hill New Hampton Tamworth Robert Daniels Vacant Tony Giunta Vacant Dr. George Luciano Patricia Farley Andover Bristol Freedom Holderness Northfield Tilton John Cotton Steve Favorite Jean Marshall Robert Snelling Wayne Crowley Joseph Jesseman Douglas Read Ashland Center Harbor Gilford Laconia Ossipee Tuftonboro Gordon McCormack, Jr. Maureen Criasia John Morgenstern Dean Anson, II Dr. Patricia Jones Dan Duffy Warren Hutchins Roger terKuile Stephen Wingate Barnstead Danbury Gilmanton Meredith Sanbornton Wolfeboro David Kerr Charlotte McIver Stanley O. -

Re: Request for Approval of Amendments to New Hampshire Surface Water Quality Standards

The State of New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Robert R. Scott Commissioner December 13, 2019 Dennis Deziel, Regional Administrator EPA New England, Region 1 5 Post Office Square - Suite 100 Boston, MA 02109-3912 Re: Request for approval of amendments to New Hampshire Surface Water Quality Standards Dear Mr. Deziel: On January 20, 2018, the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services (NHDES) made a 1 request to EPA to approve adopted amendments to the state's surface water quality standards • One of those amendments, regarding the dissolved oxygen (DO) saturation standard, was precipitated by a change in state law. Senate Bill (SB)127, effective September 8, 2017, amended State statutes (RSA 485-A:2, A:6 and A:8) regarding dissolved oxygen standards. NHDES submitted a request to EPA to add this amended statute to our approved state surface water quality standards per the requirements of 40 CFR § 131.6 and § 131.20(c ). This letter is to withdraw that request. Since submitting our request, NHDES and EPA Region 1 have been in detailed communication. A request for more information was sent by EPA to the state on July 3, 2019. NHDES responded to this letter on October 23, 2019, to which EPA replied on November 7, 2019. At the same time, NHDES has been in close communication with stakeholders and legislators regarding this issue. What is clear from all of these communications is that the issue of changing the DO saturation standard is much more complicated than originally thought. To this end, NHDES is working with the legislature to add more flexibility to the state's ability to set surface water quality standards for dissolved oxygen. -

Chapter 5: Recreation

CHAPTER 5: RECREATION Photo Compliments of: Leigh Sharps, Little Squam Lake, Ashland, NH Ashland Master Plan Chapter 5 5.1 INTRODUCTION The town of Ashland offers a range of recreational opportunities to year-round and seasonal residents. With Ashland’s excellent parks, its immediate access to Squam Lake and a number of wooded areas, the Town is a unique and highly desirable place in which to live. The Town has been generally supportive of funding proposals for recreational activities that have come up for Town Meeting votes. Land and Water Conservation Funds and donations have been used to set up a number of recreation facilities and programs in the past. 5.2 PARKS AND RECREATION 5.2.1 Staff The Town appoints a Park and Recreation Director who makes policy level decisions to manage the programming, the part-time and seasonal personnel, the town beach and campground, L.W. Packard Field, and the Booster building. Seasonal employees which may include lifeguards, swim instructors, camp counselors in the summer, and a Program Assistant to manage the After School Program during the academic year. An advisory board was established for the Parks and Recreation Department consisting of five community volunteers to assist the Director in developing programs and with fundraising efforts. Scheduled to meet monthly, the committee has not actively met since 2008. Community members are encouraged to participate and get this committee reactivated. Currently in its place, the Ashland Area Recreation Association formed in 2009 primarily to raise funds and install lights in the playing fields. It has been instrumental in continuing fundraising efforts for other projects and assisting with the upkeep and maintenance of the fields and beach. -

New Hampshire!

New Hampshire Fish and Game Department NEW HAMPSHIRE FRESHWATER FISHING 2021 DIGEST Jan. 1–Dec. 31, 2021 Go Fish New Hampshire! Nearly 1,000 fishable lakes and 12,000 miles of rivers and streams… The Official New Hampshire fishnh.com Digest of Regulations Why Smoker Craft? It takes a true fisherman to know what makes a better fishing experience. That’s why we’re constantly taking things to the next level with design, engineering and construction that deliver best-in-class aluminum fishing boats for every budget. \\Pro Angler: \\Voyager: Grab Your Friends and Head for the Water Years of Worry-Free Reliability More boat for your bucks. The Smoker Craft Pro Angler The Voyager is perfect for the no-nonsense angler. aluminum fishing boat series leads the way with This spacious and deep boat is perfect for the first feature-packed value. time boat buyer or a seasoned veteran who is looking for a solid utility boat. Laconia Alton Bay Hudson 958 Union Ave., PO Box 6145, 396 Main Street 261 Derry Road Route 102 Laconia, NH 03246 Alton Bay, NH 03810 Hudson, NH 03051 603-524-6661 603-875-8848 603-595-7995 www.irwinmarine.com Jan. 1–Dec. 31, 2021 NEW HAMPSHIRE Fish and Game Department FRESHWATER FISHING 2021 DIGEST Lakes and Rivers Galore I am new to Fish and Game, but I was born and raised in New Hampshire and have spent a lifetime working in the outdoors of our Granite State. I grew up with my friends ice fishing for lake trout and cusk on the hard waters of Lake Winnipesaukee and Lake Winnisquam with my father and his friends. -

New Hampshire Fish and Game Department

New Hampshire Fish and Game Department NEW HAMPSHIRE FRESHWATER FISHING 2016 DIGEST Jan. 1–Dec. 31, 2016 Go Fish New Hampshire! Nearly 1,000 fishable lakes and 12,000 miles of rivers and streams… The Official New Hampshire fishnh.com Digest of Regulations SAVE TODAY. SMOOTH WATER TOMORROW. See how much you could save on boat insurance. for your boat geico.com | 1-800-865-4846 | local offi ce Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by Seaworthy Insurance Company, a GEICO company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, D.C. 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. GEICO Gecko Image © 1999-2016. © 2016 GEICO Jan. 1–Dec. 31, 2016 NEW HAMPSHIRE Fish and Game Department FRESHWATER FISHING 2016 DIGEST Fish New Hampshire and Relax Greetings, anglers! With 12,000 miles of rivers and streams and 975 lakes and ponds in New Hampshire, you are never far from great fishing – and the relaxation and magnificent scenery that go with it. Angling adventures here are as diverse as the state itself. You can target native brookies in our mountain streams, bring in a big bass or laker in the Lakes Region, or head for the mighty Connecticut River, with a dozen or more different species of fish. For your fishing pleasure, we stock nearly a million rainbow, brook and brown trout, as well as landlocked ON THE COVER: salmon every year. Check out locations in the stocking reports on our mobile-friendly Rainbow Trout website at fishnh.com. -

Annual Report of the Officers of the Town of Ashland, for the Fiscal Year

NH 352o07 A82 1969 ANNUAL REPORT... Town of Ashland New Hampshire 1969 Hampshire tJtiversity of New Jlibrary —— Dates To Remember January 1 Fiscal year begins March 3 Hearing — Supervisors of Checklist 7-9 P. M. March 7 Hearing — Supervisors of Checklist 7-9 P. M. March 9 Hearing — Supervisors of Checklist 7-9 P. M. March 10 ANNUAL TOWN MEETING March 31 Motor vehicle registration expires April 1 All property both real and personal, assessed to owner this date April 15 Last day to file inventory to be eligible to make claim to abatement. RSA 77:14 Last day for veterans to file for tax exemp- tion Last day for veterans to pay in full real and personal taxes to be eligible for exemptions. May 1 Dog license tax due. (Available from Town Clerk.) Bicycle plates due. (Available from Chief of Police.) June 1 Hearing on Party Change Supervisors of Checklist 7-9 P. M. June 5 Hearing on Party Change Supervisors of Checklist 7-9 P. M. June 6 Hearing, on Party Change Supervisors of Checkhst 7-9 P. M. September 1 Hearing — Supervisors of Checklist 7-9 P. M. September 5 Hearing — Supervisors of Checkhst 7-9 P. M. September 7 Hearing — Supervisors of Checklist 7-9 P. M. September 8 PRIMARY ELECTION October 27 Hearing — Supervisors of Checklist 7-9 P. M. October 31 Hearing — Supervisors of Checklist 7-9 P. M. November 2 Hearing — Supervisors of Checklist 7-9 P. M. November 3 BIENNIAL ELECTION December 1 Unpaid real and personal taxes commence to draw interest at 6% December 31 Fiscal year closes SELECTMEN'S MEETING: Tuesday afternoons at 2 :00 P.M. -

Lakes Region

Aú Aè ?« Aà Kq ?¨ Aè Aª Ij Cã !"b$ V# ?¨ ?{ V# ?¬ V# Aà ?¬ V# # VV# V# V# Kq Aà A© V# V# Aê !"a$ V# V# V# V# V# V# V# ?¨ V# Kq V# V# V# Aà C° V# V# V# V#V# ?¬A B C D V# E F G 9.6 V#Mount Passaconaway Kq BAKERAê RIVER 10.0 Saco River WARRENWARREN 9.2 Mount Paugus Mount Chocorua 0.9 NH 25A 0.2 Peaked Hill Pond Ij Mad River Mount Whiteface V# ?Ã Noon0 Peak 2.5 5 10 V# Pequawket Pond CONWAY Mud Pond V# CONWAY ELLSWORTHELLSWORTH Aj JenningsV# Peak ?¨Iona Lake Cone Pond MilesALBANYALBANY Conway Lake LAKES REGIONNH 175 THORNTONTHORNTON WHITE MOUNTAIN NATIONAL FOREST Ellsworth Pond WATERVILLEWATERVILLEV# VALLEYVALLEY Upper Pequawket Pond Flat Mountain Ponds Snake Pond WENTWORTHWENTWORTH US 3 Sandwich MountainSandwich Dome Ledge Pond WW H H I I T T E E MM O O U U N N T T A A I I N N RR E E G G I I O O N N Whitton Pond BICYCLE ROUTES V# Haunted Pond Dollof Pond 1 I NH 49 Middle Pea Porridge Pond 1 27 Pea Porridge Pond Ae ")29 13.4 Labrador Pond 4.0 ?{ 34 Atwood Pond Aá 8.6 Campton Pond Black Mtn Pond Lonely Lake Davis Pond Tilton Pond Câ James Pond 14.1 Chinook Trail South Branch Moosilauke Rd 13.0 2.1 Chase Rd Chocorua Lake RUMNEYRUMNEY 2.8 ")28 Great Hill Pond fg Tyler Bog Roberts Pond 2.0 Guinea Pond Little Lake Blue PondMADISONMADISON R-5 4.2 HEMMENWAY STATE FOREST Mack Pond Loud Pond NH 118 Pemigewasset River 5.1 Mailly Pond Drew Pond 3.7 fg Buffalo Rd CAMPTON Hatch PondEATONEATON 5.3 CAMPTON Baker River Silver Pond Beebe River ?¬ Quincy Rd Chocorua Rd DORCHESTERDORCHESTER 27 0.8 Durgin Pond ") SANDWICHSANDWICH 4.5 Loon Lake BLAIR STATE -

Annual Report of the Officers of the Town of Holderness, New

ANNUAL REPORT HOLDERNESS NEW HAMPSHIRE 'Htm $~ Welcome to Holderness Signs Compliments ofHolderness 2000, Rockywold-Deephaven Camps and the Holderness Highway Department. Year ending December 31, 1995 COVER PHOTO Left to right: Kenneth Knowton - Dept. of Transportation, Bureau ofEnvironment, Special Services Philip Zimmer - Rockywold-Deephaven Camps Roy Bickford - Holderness Highway Dept. John Jurczynski - Rockywold-Deephaven Camps Wilson Earl - Holderness Highway Dept. William Zimmer - Rockywold-Deephaven Camps Stuart Sherburne - Holderness Highway Dept. ANNUAL REPORT of the OFFICERS of the TOWN OF HOLDERNESS New Hampshire Year Ending December 31, 1995 CONTENTS List of Town Officers 5 Selectmen's Report 7 Town Administrator's Report 10 Procedure of Town Meeting March 1995 11 Public Safety and Road Maintenance Building Committee 19 Police Department 21 Fire Department Report 23 Forest Fire Warden Report 25 Recreation Board Report 27 Holderness Free Library Report 28 Holderness Historical Society Report 30 Planning Board Report 31 Lakes Region Planning Commission Report 32 Zoning Board of Adjustment Report 34 Conservation Commission Report 35 Compliance Officer's Report 36 Town Clerk's Report 36 White Oak Solid Waste District Report 37 Vital Statistics 38 Tax Collector's Report 43 Overseer of Welfare Report 45 Inter Lakes Day Care Center & Nursery School Report 46 Pemi-Baker Home Health Agency Report 47 Pemi-Baker Youth and Family Services Council Report 48 Task-Force Against Domestic & Sexual Violence Report 49 Tri County Community Action -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT TOWN OF ASHLAND NEW HAMPSHIRE FISCAL YEAR ENDING DECEMBER 31, 2014 INFORMATIONAL TOWN OF ASHLAND – GRAFTON COUNTY POPULATION – 2075 DATE OF INCORPORATION – 1868 LAT 43.695ºN LON 71.631ºW ELEVATION 551' TELEPHONE COMPANY – FAIRPOINT CABLE – TIME WARNER TOWN OFFICE – 20 HIGHLAND STREET HOURS – MON, TUES, WED, FRI 8-4, THURS 8-5 WELFARE OFFICE HOURS – TUESDAYS 5:00 TO 7:00 pm BUILDING INSPECTOR HOURS – MON, WED, & FRI 10:00 – 12:00 pm ADMINISTRATION TOWN ADMINISTRATOR 968-4432 ASSESSING TOWN OFFICE 968-4432 BUILDING PERMITS BUILDING INSPECTOR 968-4432 BURN PERMITS FIRE DEPARTMENT 968-7772 DOGS-LICENSING TOWN CLERK 968-4432 DOGS – AT LARGE POLICE DEPARTMENT 968-4000 ELECTIONS TOWN CLERK 968-4432 VOTER REGISTRATION TOWN CLERK 968-4432 ELECTRIC SERVICE ASHLAND ELECTRIC 968-3083 HEALTH OFFICER TOWN OFFICE 968-4432 TOWN LIBRARY SCRIBNER LIBRARY 968-7928 VEHICLE REGISTRATION TOWN CLERK 968-4432 LAND USE – PLANNING/ZONING TOWN OFFICE 968-4432 POLICE POLICE DEPARTMENT 968-4000 PARKS AND RECREATION P/R DEPARTMENT 968-9209 RECYCLING TRANSFER STATION 968-9032 ROAD MAINTENANCE PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT 968-3166 SCHOOLS ASHLAND ELEMENTARY 968-7622 PLYMOUTH REGIONAL HS 536-1444 PROPERTY TAXES TAX COLLECTOR 968-4432 VITAL RECORDS TOWN CLERK 968-4432 WATER/SEWER DEPARTMENT BILLING OFFICE 968-4002 TREATMENT PLANT 968-7193 WELFARE TOWN OFFICE 968-4432 OUTSIDE AGENCIES FOOD PANTRY COMMUNITY CENTER 968-9698 PEMI BAKER HOME HEALTH 536-2232 ASHLAND POST OFFICE 968-7511 FUEL ASSISTANCE – TRI COUNTRY CAP 968-3560 TABLE OF CONTENTS We Remember .......................................................................................................................................................................................