Norwegian Cruise Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Cruise Ship Schedule

Bermuda 2016 CRUISE SHIP SCHEDULE Compiled by the Department of Marine and Ports Services Information subject to change without notice Dated: February 2, 2016 www.marineandports.bm KEY Anc GS At Anchor in Great Sound Ham 5/6 Hamilton, #5/6 Passenger Terminal KW King’s Wharf, Dockyard HW Heritage Wharf, Dockyard Pennos Pennos, St. Georges MA MEYER SHIPPING Phone: 296-9798 ALG All Leisure Group PLC CAR Carnival Cruise Line CC Crystal Cruises CEL Celebrity Cruises FOL Fred Olsen Line HAL Holland American Line MSC MSC Cruises NCL Norwegian Cruise Line PCH Prestige Cruise Holdings, Oceania Cruises & Regent Seven Seas Cruises PCL Princess Cruise Lines RCI Royal Caribbean International VC Viking Cruises BSA BERMUDA SHIP AGENCIES LTD. Phone: 294 - 1401 AID AIDA Cruises CR Cambiaso & Risso TUI TUI UK Limited/Columbia Cruise Services VSL V - Ships Leisure SAM CRUISE DESTINATIONS BAL Baltimore HAV Havana, Cuba NY New York BOS Boston HOR Horta, Azores PC Port Canaveral, Florida CAP Cape Liberty GT Grand Turks PE Port Everglades CHA Charleston LIS Lisbon PAN Panama CRT Cartagena, MIA Miami PDG Punta Delgada, Azores Columbia COB Cobh, Ireland NAS Nassau, SB St. Barts Bahamas FNM Funchal, NOR Norfolk, SJ St. Johns, Antigua Madeira Virginia HAL Halifax TOR Tortola, BVI TAM Tampa, Fl Regular Callers/Contract Ships - Usual Weekly Schedule Arrival and Departure times of ships in the schedule are at/from the berth. Times are subject to change without notice - due to weather/operational reasons. Times may vary significantly, particularly at beginning and end of season – check schedule carefully. Occasional callers are highlighted throughout the schedule in blue. -

Unscheduled Foreign & Maiden Norwegian

Unscheduled PORT OF PORTLAND, MAINE Foreign Arrival Maiden Voyage 2018 BERTHING SCHEDULE Foreign & Maiden revised 11/7/2018 BILLED VESSEL NAME ARRIVAL TIME DEPART TIME ARR-DAYDEP-DAY BERTH AGENT LINE BOOKED SHIP DETAILS PAX Crew Artania 4/25/18 7:00 4/25/18 14:00 Wed Wed POT CLCO Artania Shipping 12/15/2016 LOA 757-B 107-D 43 1200 520 FRAM 4/28/18 7:45 4/28/18 20:00 Sat Sat POT Inchcape HCL 5/23/2017 LOA 374 B 66 D 16.7 318 Marina 4/29/18 800 4/29/18 22:00 Sun Sun POT Intercruise OC 5/23/2013 LOA 785 1171 800 MAY Pearl Mist 5/6/18 13:00 5/19/18 15:00 Sun Sat OG CLCO PS 1/4/2017 LOA 335-B 56 D 12 197 65 Maasdam 5/13/18 8:00 5/13/18 16:00 Sun Sun POT CLCO HAL 6/24/2014 LOA 720-B 102-D 25 1258 618 Grandeur of the Seas 5/13/18 8:00 5/13/18 17:00 Sun Sun P2B2 MLS RCI 7/29/2016 LOA 918-B 106-D 26 2000 790 Victory 1 5/13/18 8:00 5/15/18 tbd Sun Tue OG CLCO VCL 1/16/2018 LOA 286 B 49 D 13.5 200 90 American Constitution 5/20/18 23:30 5/21/18 19:00 Sun Mon POT ACL ACL 2/2/2017 LOA 267 165 Hebridean Sky 5/25/18 7:00 5/25/18 18:00 Fri Fri POT Inchcape PC 7/8/2016 LOA 297-B 50-D 14 118 70 American Constitution 5/30/18 22:30 5/31/18 19:00 Sun Mon POT ACL ACL 2/2/2017 LOA 267 165 JUNE Independence 6/1/18 17:00 6/2/18 13:30 Fri Sat POT ACL ACL 2/2/2017 LOA 215 98 26 Adventure of the seas 6/3/18 7:00 6/3/18 18:00 Sun Sun P2B2 MLS RCI 7/29/2016 LOA 1020-B 158-D 29 3114 1120 Norwegian Gem 6/7/18 8:00 6/7/18 20:00 Thu Thu POT Intercruise NCL 1/31/2017 LOA 964-B 106-D 58 2690 1101 Independence 6/8/18 17:00 6/9/18 13:30 Fri Sat POT ACL ACL 2/2/2017 LOA 215 -

Cruise Vessels & Ferries

FROM OUR DESIGN PORTFOLIO CRUISE VESSELS & FERRIES Expedition Cruise Vessels (Endeavor Class) 2017 -19 Client / Shipyard: MV WERFTEN, Stralsund, Germany Owner / Operator: Genting International Plc., Malaysia / Crystal Yacht Expedition Cruises, USA ICE Scope of work: Basic Design Assistance & Detail Crystal Endeavor. Class: DNV GL Design. All-Electric Ferry Concept Design 2018 -19 Type: Battery Electric Ferry Duty: Passenger and Car Ferry Capacity: 200 passengers and 45 cars. Speed: 15 knots in open water and operating with 10 knots in harbour. AIDAprima cruise ship. Client / Shipyard: Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI). ICE Scope of work: Coordination drawings. Class: DNV GL International Contract Engineering Ltd. © 2019 International Contract Engineering Ro-Ro Passenger Ferry 2003 -04 Client / Shipyard: Chantiers de l' Atlantique, France Owner: Euro-Transmanche 3 BE (2012-Present); Seafrance (2005-2012) Operator: DFDS Seaways France ICE Scope of Work: Detail design: Côte Des Flandres (ex SeaFrance Berlioz (2005-2012)). Yard number O32. Class: BV - hull structure for the entire vessel - machinery & tanks area. Fast Displacement Ro-Ro Passenger Ferry 1999 -02 Client / Shipyard: Hellenic Shipyard, Greece Owner / Operator: Hellenic Seaways ICE Scope of work: 3-D Model (Tribon); Detail design (hulls 1701 and 1702): Coordination drawings, workshop drawings and production information for all disciplines; Full ship FE model. Armand Imbeau II. Class: Lloyd’s Register LNG-powered Ro-Pax Ferry 2013 Client / Shipyard: Chantier Davie Canada Inc. Operator: Société des Traversiers du Québec (STQ) ICE Scope of work: Concept design review; Design planning and scheduling; Design risk analysis; Nissos Mykonos. Class: BV Initial 3-D modeling (Tribon). Oasis of the Seas, the first of the Oasis Class (formerly the Genesis Class). -

2016 Cruise Guide

CRUISE CAPITAL OF THE WORLD GLOBAL GATEWAY 2016 Cruise Guide GLOBAL GATEWAY 2016 Cruise Guide 2 Cruising from PortMiami is Only Getting Better More Cruise Brands and New Build Ships It is an exciting time at PortMiami! There is no doubt that PortMiami’s cruise facilities are the most modern in the the Cruise Capital of the World continues to expand as world, providing easy passenger boarding and departure. the world’s leading cruise port. Last year PortMiami By continuously investing in cruise facility improvements, set another word record in cruise passengers, nearly PortMiami maintains its position as market leader and 4.9 million sailed through PortMiami - more than any is prepared for the newest generation of cruise vessels. other port in the world. Currently on the drawing board are plans to expand the cruise footprint, including options for new cruise berths PortMiami is poised for yet another exceptionally strong and terminals as well as associated intermodal and cruise season as it welcomes a host of new cruise brands parking facilities. and new build ships that rank among the most innovative vessels on the seas today. With 19 cruise brands berthing 42 ships PortMiami is clearly the departure destination of choice for cruises to New for the 2015-16 cruise season is the arrival of the Bahamas, the Caribbean, Mexico and beyond, offering Norwegian Cruise Line’s new build ship, the Norwegian cruise vacations for every taste and budget - from family Escape. Many of PortMiami’s current cruise partners fun to luxury cruising. PortMiami’s ships have amenities are also expanding their Miami fleets. -

Ations Corporation Publication May/June 2015 Vol

A COASTAL COMMUNICATIONS CORPORATION PUBLICATION MAY/JUNE 2015 VOL. 22 NO.3 $10.00 Incentives at Sea New & Different and Bigger & Better Than Ever Before Page 10 The flagship of the Oceania Cruises fleet — the luxurious Regatta — in the port of Quebec City. Credit: Oceania Cruises Credit: Special Social Media Page 18 Info Security Page 60 pullout section R SAY BON VOYAGE TO ORDINARY AND WELCOME ABOARD TO EXTRAORDINARY MEMORABLE EVENTS, MEETINGS AND INCENTIVES BEGIN WITH A STUNNING SETTING. Amazed. Engaged. Rejuvenated. When was the last time you felt that way about an event or conference? You will on a Royal Caribbean® cruise. Our innovative turnkey solutions will dazzle you with everything from complimentary fine dining and state-of-the-art conference rooms to unforgettable venues and spectacular Broadway-style shows. And all for one very aordable price. Talk to one of our Corporate Sales Managers today to start planning a unique program that your clients are sure to enjoy — and remember. The only thing cookie-cutter about our special events … is the mold we use to create your logo-inspired desserts. Contact us today and learn more. (800) 345-7225 (select 2, then 1) or visit RoyalCaribbeanIncentives.com BEST CRUISE LINE OVERALL Travel Weekly Readers’ Choice Awards YEAR12S RUNNING 2003 – 2014 Features vary by ship. ©2015 Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd. Ships’ registry: The Bahamas. 15044342 • 5/12/2015 ISSN 1095-9726 .........................................USPS 012-991 A COASTAL COMMUNICATIONS CORPORATION PUBLICATION MAY/JUNE 2015 Vol. 22 No. 3 Credit: Benchmark Conference Centers Conference Benchmark Credit: Page 54 Stonewall Resort in Roanoake, West Virginia, is a certified Benchmark FEATURES Conference Center. -

Military Rates

Military Rates Updated Friday, October 12, 2012 CAT Cat CAT Ocean CAT CAT Mini- PROMO SHIP SAIL DATE ITINERARY NIGHTS Studio Inside Balcony Mini- Studio Inside view Outside Balcony Suite CODE Suite NORWEGIAN DAWN 12/9/2012 Western Caribbean - Tampa 7 $449 IX $467 OX $737 BX 781.6 MX MILITARY NORWEGIAN EPIC 12/8/2012 Eastern Caribbean - Miami 7 $768 T1 $467 IX $768 BX 988.6 MD MILITARY NORWEGIAN JADE 10/20/2012 Europe - Mediterranean & Holy Land - Rome 11 $466 IX $551 OX MILITARY NORWEGIAN JADE 10/31/2012 Eastern Mediterranean 10 $407 IF $424 OX $551 BX 891.15 MX MILITARY NORWEGIAN JADE 11/10/2012 Europe - Mediterranean & Holy Land - Rome 11 $679 IX $679 OX $891 BX 933.65 MX MILITARY NORWEGIAN JADE 11/21/2012 Eastern Mediterranean 10 $415 IF $441 OX $611 BX 806.15 MX MILITARY NORWEGIAN JADE 12/1/2012 Europe - Mediterranean & Holy Land - Rome 11 $492 IX $551 OX $636 BX 806.15 MX MILITARY NORWEGIAN JADE 12/12/2012 Eastern Mediterranean 10 $407 IX $449 OX $636 BX 806.15 MX MILITARY NORWEGIAN JADE 12/22/2012 Europe - Mediterranean & Holy Land - Rome 11 $1,146 OX $1,529 BX 1996.15 MX MILITARY NORWEGIAN JEWEL 10/28/2012 Bahamas - New York 7 $365 IX $467 OX $647 BX 853.6 MX MILITARY NORWEGIAN JEWEL 11/11/2012 Bahamas - New York 7 $449 IX $539 OX $692 BX 781.6 MX MILITARY NORWEGIAN JEWEL 12/2/2012 Bahamas - New York 7 $422 IX $494 OX $647 BX 736.6 MX MILITARY NORWEGIAN JEWEL 12/9/2012 Bahamas - New York 7 $422 IX $467 OX $647 BX 736.6 MX MILITARY NORWEGIAN JEWEL 12/16/2012 Bahamas - New York 7 $467 IX $467 OX $647 BX 736.6 MX MILITARY NORWEGIAN -

Ship Codes SHIPCODE SHIP MAX

Cruise Line Agencies of Alaska Ship Codes SHIPCODE SHIP MAX. PASSENGERS JOB CODE SERVICES CRUISELINE AMC AMERICAN CONSTELLA 230 0 BTGRP AMERICAN CRUISES AMD AMSTERDAM 1460 0 GTBPR HOLLAND AMERICA LINE ARC ARCADIA 1850 0 BTPGR CARNIVAL UK ASK ASUKA 960 BPGT NYK BAL BALMORAL 1070 0 BPTGR FRED OLSEN CRUISE LINE BMN BREMEN 166 0 BPTRG HAPAG-LLOYD BRL BRILLIANCE 2100 0 GTBRP RCCL CDY CROWN DYNASTY 800 0 BPRG CUNARD LINE CEN CENTURY 1750 0 BTGRP CELEBRITY CRUISE LINE CHM CRYSTAL HARMONY 960 0 BTGPR CRYSTAL CRUISE LINE CLD CALEDONIAN SKY 115 0 BTPRG SALEN SHIP CLG CARNIVAL LEGEND 2124 0 BTGRP CANRIVAL CRUISE LINE CLO CLIPPER ODYSSEY 120 0 BGR NEW WORLD SHIP MANAGEMENT CLP CLIPPER PACIFIC 1196 0 BPTR JAPAN GRACE CMR CARNIVAL MIRACLE 2124 0 BTGRP CARNIVAL CRUISE LINE CON CONTESSA 49 0 BG MAJESTIC AMERICA LINE COR CORAL PRINCESS 1992 0 BTGPR PRINCESS CRUISE LINES COS COSTA RIVIERA 1000 0 BPTG COSTA CRUISE LINE CPD CARNIVAL PRIDE 2024 0 BTPG CARNIVAL CRUISE LINE CRP CROWN PRINCESS 1590 0 BPRGT PRINCESS CRUISES CRS CRYSTAL SERENITY 1080 0 BPTGR CRYSTAL CRUISES CSD CARNIVAL SPLENDOR 3000 0 BTGRP CARNIVAL CRUISE LINE CSM CRYSTAL SYMPHONY 900 0 BPGRT CRYSTAL CRUISES CSP CARNIVAL SPIRIT 2124 0 BTGPR CARNIVAL CRUISE LINES CWN CROWN PRINCESS 3082 0 BTPRG PRINCESS CRUISE LINES DMD DIAMOND PRINCESS 2600 0 GTRPB PRINCESS CRUISESS DNP DAWN PRINCESS 1950 0 BPTGR PRINCESS CRUISES DRM DREAMWARD 1246 0 BRP NORWEGIAN CRUISE LN DSW DISNEY WONDER 2400 0 BTGRP DISNEY CRUISE LINE ECL ECLIPSE 2850 0 BTRGP CELEBRITY CRUISE LINE EMP EMERALD PRINCESS 3082 0 BTPGR PRINCESS -

Norwegian Cruise Line Corporate Overview

NORWEGIAN CRUISE LINE CORPORATE OVERVIEW Norwegian Cruise Line is the innovator in cruise travel with a 44-year history of breaking the boundaries of traditional cruising, most notably with the introduction of Freestyle Cruising which has revolutionized the industry by allowing guests more freedom and flexibility. Today, Norwegian has 11 purpose-built Freestyle Cruising ships providing guests the opportunity to enjoy a relaxed cruise vacation on some of the newest and most contemporary ships at sea. In 2010, the Company reached an agreement with MEYER WERFT GMBH of Germany to build two new next generation Freestyle Cruising ships for delivery in spring 2013 and spring 2014, respectively. Each of the 143,500 gross ton vessels, the largest passenger/cruise ships to be built in Germany, will have approximately 4,000 passenger berths and a rich cabin mix. In February 2000, Norwegian was acquired by Genting Hong Kong Limited formerly Star Cruises Ltd (SES: STRC), a Hong Kong stock exchange listed company, and part of Malaysia's Genting Group. Following the acquisition of Norwegian, Star Cruises became the third largest cruise line in the world. While under 100 percent ownership by Star, the company embarked on an expansion program that involved new ships, on-board product enhancements and innovative itineraries. In August 2007, private equity group, Apollo Management, LP, agreed to make a $1 billion cash equity investment in Norwegian. Under the terms of the investment which closed on January 7, 2008, Apollo became a 50 percent owner of Norwegian and has named a majority of the company’s board with certain consent rights retained by Genting. -

Nycruise 2017 Schedule*

NYCRUISE 2017 SCHEDULE* January 6/18 Norwegian Breakaway 1/2 Norwegian Breakaway 6/20 Carnival Sunshine 1/3 Queen Mary 2 6/24 Norwegian Gem 1/8 Norwegian Gem 6/25 Norwegian Breakaway 1/15 Norwegian Breakaway, 6/27 MS Insignia Queen Elizabeth 6/28 MS Insignia, 1/16 Queen Elizabeth Carnival Sunshine 1/18 Norwegian Gem 1/28 Norwegian Gem July 1/29 Norwegian Breakaway 7/1 Norwegian Gem, Queen Mary 2 February 7/2 Norwegian Breakaway 2/7 Norwegian Gem 7/6 Carnival Sunshine, 2/12 Norwegian Breakaway Queen Mary 2, Europa 2 2/17 Norwegian Gem 7/7 Europa 2 2/19 Norwegian Breakaway 7/8 Norwegian Gem 2/26 Norwegian Breakaway 7/9 Norwegian Breakaway 2/27 Norwegian Gem 7/10 MS Insignia, Carnival Sunshine March 7/15 Norwegian Gem 3/5 Norwegian Breakaway 7/16 Norwegian Breakaway 3/9 Norwegian Gem 7/18 Carnival Sunshine 3/12 Norwegian Breakaway 7/22 Norwegian Gem 3/19 Norwegian Breakaway, 7/23 Norwegian Breakaway Norwegian Gem 7/26 Carnival Sunshine 3/26 Norwegian Breakaway 7/27 Sea Princess 3/29 Norwegian Gem 7/28 Sea Princess, Queen Mary 2 April 7/29 Norwegian Gem 4/2 Norwegian Breakaway 7/30 Norwegian Breakaway 4/8 Norwegian Gem 4/9 Norwegian Breakaway August 4/16 Norwegian Breakaway 8/3 Carnival Sunshine 4/18 Norwegian Gem 8/5 Norwegian Gem 4/19 Amadea 8/6 Norwegian Breakaway 4/20 Amadea 8/7 Carnival Sunshine 4/23 Norwegian Breakaway 8/9 MS Insignia 4/29 Norwegian Gem 8/10 MS Insignia 4/30 Norwegian Breakaway 8/11 Seven Seas Navigator 8/12 Norwegian Gem, Carnival May Sunshine, Seven Seas 5/6 Norwegian Gem Navigator, Queen Mary 2 5/7 Norwegian Breakaway -

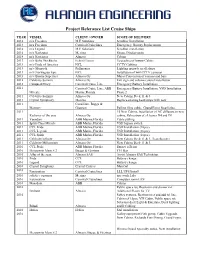

Project Referance List Cruise Ships

Project Referance List Cruise Ships YEAR VESSEL CLIENT / OWNER SCOPE OF DELIVERY 2014 m/s Freedom M.E Solutions Scrubber Installation 2014 m/s Freedom Carnival Cruiselines Emergency Battery Replacement 2014 m/s Legend M.E Solutions Scrubber installation 2014 m/s Navigator Merima Shops, Display units 2014 m/s Navigator Almaco Cabins 2013 m/s Birka Stockholm Eckerö Linjen Upgrading of luxury Cabins 2013 m/v Pride of America NCL CCTV Cabling 2013 m/v Monarch Pullmantur Lighting upgrade in all shops 2013 m/v Norwegian Epic NCL Installation of 660 CCTV cameras 2013 m/v Bimini Superfast Almaco Oy Major Conversion of casinos and bars 2012 Celebrity Summit Almaco Oy Exit sign and volume control installation 2012 Conquest/Glory Carnival Cruise Line Emergency Battery Installation 2011 Carnival Cruise Line, ABB Emergency Battery Installation, VSD Installation Mircale Marine,Florida Phase 2 2011 Celebrity Summit Almaco Oy New Cabins Deck 11 & 3 2011 Crystal Symphony. Merima Replace existing heat lamps with new 2011 Consilium, Bugge & Mercury Gjertsen Pulling fibre cable, Grand Foyer Step lights. 2011 15 New Cabins, Installation of AC diffusers in new Radiance of the seas. Almaco Oy cabins, Relocation of el. boxes D4 and D9 2011 Veendam ABB Marine,Florida Cable pulling 2011 Spirit Class Miracle ABB Marine,Florida VSD bypass switch 2011 CCL Pride ABB Marine,Florida VSD Installation (16pcs) 2011 CCL Legend ABB Marine,Florida VSD Installation (16pcs) 2011 CCL Spirit ABB Marine,Florida VSD Installation (16pcs) 2011 Celebrity Infinity Almaco Oy New Cabins Deck 11 & 3, Transformers 2011 Celebrity Millennium Almaco Oy New Cabins Deck 11 & 3 2010 CCL Pride ABB Marine Florida Energy efficent 2010 Mercury to Mein S 2 Bugge & Gjertsen TUI Bar 2010 Allur of the seas. -

BLÜCHER Marine References

BLÜCHER Marine References Country Project Shipyard Owner Vessel Type Hull no. Year Argentina Frigate Naval Shipyard Frigate Frigate Refitting 2005 Australia Australian Customs and Austal Ships Australian Customs and Border Cape Class Patrol Boat 361 2013 Border Protection Service Protection Service Australia Australian Customs and Austal Ships Australian Customs and Border Cape Class Patrol Boat 362 2013 Border Protection Service Protection Service Australia Australian Customs and Austal Ships Australian Customs and Border Cape Class Patrol Boat 363 2013 Border Protection Service Protection Service Australia Australian Customs and Austal Ships Australian Customs and Border Cape Class Patrol Boat 364 2013 Border Protection Service Protection Service Australia Australian Customs and Austal Ships Australian Customs and Border Cape Class Patrol Boat 365 2014 Border Protection Service Protection Service Australia Australian Customs and Austal Ships Australian Customs and Border Cape Class Patrol Boat 366 2014 Border Protection Service Protection Service Australia Australian Customs and Austal Ships Australian Customs and Border Cape Class Patrol Boat 367 2014 Border Protection Service Protection Service Australia Australian Customs and Austal Ships Australian Customs and Border Cape Class Patrol Boat 368 2014 Border Protection Service Protection Service Australia Australian Defence Civmec/ASC Australian Defence OPV OPV1 2019 Australia Australian Defence - ASC Shipyard Australian Defence Air Warfare Destroyer 2012 AWD Australia Australian Defence - LHD BAE Systems Australian Defence Landing Helicpoter 2012 Dock Australia Dick Smith Tenix Dick Smith Ocean Research Ulysses Blue 2005 Vessel Australia Esso West Tuna Esso Platform 1996 Australia HMAS Arunta BAE Systems Australian Defence ANZAC Frigate ANZAC 2019 Australia Jean de la Valette - Virtu Austal Ships Virtu Ferries High Speed Ferry 248 2010 Ferries Australia RNZN Tenix RNZN Ocean Research 42826 2006 Vessel Australia Taylor Bros. -

2020 Cruise Ship Schedule

Bermuda 2020 CRUISE SHIP SCHEDULE Compiled by the Department of Marine and Ports Services Information subject to change without notice Dated: 27th December, 2019 www.marineandports.bm KEY Anc GS At Anchor in Great Sound Ham 5/6 Hamilton, #5/6 Passenger Terminal KW King’s Wharf, Dockyard HW Heritage Wharf, Dockyard Pennos Pennos, St. Georges MA MEYER SHIPPING Phone: 296-9798 CAR Carnival Cruise Line CC Crystal Cruises CEL Celebrity Cruises CUN Cunard UK DIS Disney Cruise Line FOL Fred Olsen Line HAP Hapag Lloyd Cruises INC Inchcape Shipping MSC MSC Cruises NCL Norwegian Cruise Line PB Peace Boat PCH Prestige Cruise Holdings, Oceania Cruises & Regent Seven Seas Cruises RCI Royal Caribbean International SAG Saga Shipping TUI TUI Group VC Viking Cruises BSA BERMUDA SHIP AGENCIES LTD. Phone: 294 - 1401 AID AIDA Cruises CDP Compagnie Du Ponant VSL V - Ships Leisure SAM CRUISE DESTINATIONS BAL Baltimore HMC Half Moon Cay, QUE Quebec City, Canada Bahamas BOS Boston HOR Horta, Azores REY Reykjavik, Iceland BRT St. Barts LIS Lisbon,Portugal RI Newport, Rhode Island CAP Cape Liberty MIA Miami SJ St. Johns, Antigua CCY Coco Cay, Bah. CHA Charleston MTG Montego Bay SHP Southampton, England FNM Funchal, NOR Norfolk, Virginia SL St. Lucia Madeira FRE Freeport, Bah NAS Nas Bahamas SM St. Maarteen GSC Great Stirrup NY New York TAM Tampa, Florida Cay, Bahamas GT Grand Turk, PC Port Canaveral, TOR Tortola Island, BVI Turks & Caicos Florida HAL Halifax PDG Punta Delgada Capacities – 2020 Name of Ship Number of Length Projected Number of Visits overall number