Interview with Stephen Schnorf # ISG-A-L-2010-018 Interview # 1: February 23, 2010 Interviewer: Mike Czaplicki – ALPL Oral History Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Record Producer As Nexus: Creative Inspiration, Technology and the Recording Industry

The Record Producer as Nexus: Creative Inspiration, Technology and the Recording Industry A submission presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glamorgan/Prifysgol Morgannwg for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael John Gilmour Howlett April 2009 ii I certify that the work presented in this dissertation is my own, and has not been presented, or is currently submitted, in candidature for any degree at any other University: _____________________________________________________________ Michael Howlett iii The Record Producer as Nexus: Creative Inspiration, Technology and the Recording Industry Abstract What is a record producer? There is a degree of mystery and uncertainty about just what goes on behind the studio door. Some producers are seen as Svengali- like figures manipulating artists into mass consumer product. Producers are sometimes seen as mere technicians whose job is simply to set up a few microphones and press the record button. Close examination of the recording process will show how far this is from a complete picture. Artists are special—they come with an inspiration, and a talent, but also with a variety of complications, and in many ways a recording studio can seem the least likely place for creative expression and for an affective performance to happen. The task of the record producer is to engage with these artists and their songs and turn these potentials into form through the technology of the recording studio. The purpose of the exercise is to disseminate this fixed form to an imagined audience—generally in the hope that this audience will prove to be real. -

Steve Hillage Green Mp3, Flac, Wma

Steve Hillage Green mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: Green Country: France Released: 1978 Style: Psychedelic Rock, Prog Rock, Ambient MP3 version RAR size: 1261 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1241 mb WMA version RAR size: 1618 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 516 Other Formats: MPC WMA DTS AC3 MIDI MP3 AAC Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Sea Nature Ether Ships 2 Drums – Andy Anderson 3 Musik Of The Trees 4 Palm Trees (Love Guitar) Unidentified (Flying Being) 5 Written-By – Curtis Robertson, Miquette Giraudy, Steve Hillage U.F.O. Over Paris 6 Written-By – Charles Bynum, Curtis Robertson, Joe Blocker, Miquette Giraudy, Steve Hillage 7 Leylines To Glassdom 8 Crystal City 9 Activation Meditation The Glorious Om Riff 10 Written-By – C.O.I.T.*, Hillage* Bonus Tracks Unidentified (Flying Being) (Live At Glastonbury 1979) Bass – Paul FrancisDrums – Andy AndersonGuitar, Synthesizer, Voice – Steve 11 HillageRhythm Guitar, Guitar [Glissando] – Dave Stewart Synthesizer, Voice – Miquette GiraudyWritten-By – Curtis Robertson, Miquette Giraudy, Steve Hillage Not Fade Away (Glid Forever) (Live At The Rainbow Theatre 1977) Bass – Colin BassDrums – Clive BunkerGuitar, Voice – Steve HillageKeyboards – Phil 12 HodgeRhythm Guitar, Guitar [Glissando] – Christian Boule*Synthesizer – Basil BrooksSynthesizer, Voice – Miquette GiraudyWritten-By – Charles Hardin, Norman Petty Octave Doctors (Live At Glastonbury 1979) Bass – Paul FrancisDrums – Andy AndersonGuitar, Synthesizer, Voice – Steve 13 HillageRhythm Guitar, Guitar [Glissando] – Dave Stewart -

2 to Be Somebody: Ambition and the Desire to Be Different

2 To Be Somebody: Ambition and the Desire to Be Different The context for difference This chapter aims to identify some of the bands that enjoyed chart success during the late 1970s and ’80s and identify their artistic traits by means of conversations with band members and those close to the bands. This chapter does not claim to be a definitive account or an inclusive list of innovative bands but merely a viewpoint from some of the individuals who were present at the time and involved in music, creativity and youth culture. Some of these individuals were in the eye of the storm while others were more on the periphery. However, common themes emerge and testify to the Scouse resilience identified in the previous chapter. Also, identifying objective truth is a difficult task, as one band member will often have a view of his band’s history that conflicts with that of other members of the same band. As such, it is acknowledged that this chapter presents only selective viewpoints. Trying something new: In what ways were the Liverpool bands creative and different? ‘Liverpool has always made me brave, choice-wise. It was never a city that criticized anyone for taking a chance.’ David Morrissey1 In terms of creativity, the theory underpinning this book which was stated in Chapter 1 is that successful Liverpool bands in the 1980s were different from each other and did not attempt to follow the latest local or national pop music trends. None of the bands interviewed falls into the categories of punk, disco or New Romantic, which were popular trends at the time. -

Tim Blake Interview EXCLUSIVE: Joey Molland Remembers the Glory Days

EXCLUSIVE: Tim Blake Interview EXCLUSIVE: Joey Molland remembers the glory days of Apple EXCLUSIVE: Cyrille Verdeaux and the Amazonian chieftain EXCLUSIVE: Behind the scenes of the Psychedelic Warlords EXCLUSIVE: The naked performance artist takes on Paypal. Will she win? We certainly hope so. 2 magazine, which would cover the music and culture (and the attendant lifestyle and politics) that interested me, and I realised then that now I was being given the chance. As I have always admitted, I am growing up in public and that I have no real long term plan with any of the things that I do, except to seize the opportunities that I can, and basically make it up as I go along, going in whatever direction the Fates send me. Which is basically how I live my life. So this new advancement is allowing me to produce something that is far more like a magazine than it was before. I am very much an old fashioned sort of fellow, and don’t really like many new fangled things. E-books are a particular gripe of mine—I have an e-book reader (mainly because they were incredibly cheap at Asda) and I use it mostly for reading pdfs of technical journals in bed, or reading So welcome to the first issue of the new look Gonzo P.G. Wodehouse novels whilst I am travelling Weekly. somewhere, but for me at least the e-book has only a very limited appeal. I am always amazed at how fast technology advances and how we can all do things now that E-magazines, however, are an entirely different would have been unthinkable even five years ago. -

Section III - Acknowledgements

Section III - Acknowledgements Mike Berger TPWD Wildlife Division Director Larry McKinney TPWD Coastal Fisheries Director Phil Durocher TPWD Inland Fisheries Director Lydia Saldana TPWD Communications Division Director TPWD Program Director, Science Research and Diversity Program - Ron George Wildlife Division (Retired) Technical Assistance Andy Price Texas Parks and Wildlife - Wildlife Division Bob Gottfried Texas Parks and Wildlife - Wildlife Division Cliff Shackelford Texas Parks and Wildlife - Wildlife Division Duane Schlitter Texas Parks and Wildlife - Wildlife Division Gary Garrett Texas Parks and Wildlife - Inland Fisheries Division John Young Texas Parks and Wildlife - Wildlife Division Mike Quinn Texas Parks and Wildlife - Wildlife Division Paul Hammerschmidt Texas Parks and Wildlife - Coastal Fisheries Division (Retired) Wildlife Diversity Policy Advisory Committee Terry Austin (chair) Audubon Texas (retired) Damon Waitt Brown Center for Environmental Education - Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center David Wolfe Environmental Defense Don Petty Texas Farm Bureau Doug Slack Texas A & M University, Department of Wildlife & Fisheries Sciences Evelyn Merz Lone Star Chapter of the Sierra Club Jack King Sportsmen’s Conservationists of Texas Jennifer Walker Lone Star Chapter of the Sierra Club Jim Bergan The Nature Conservancy of Texas Jim Foster Trans-Texas, Davis Mountain and Hill Country Heritage Association Kirby Brown Texas Wildlife Association Matt Brockman Texas and Southwestern Cattleraisers Association Mike McMurry Texas Department of Agriculture Phil Sudman Texas Society of Mammalogists Richard Egg Texas Soil and Water Conservation Board Susan Kaderka National Wildlife Federation, Gulf States Field Office Ted Eubanks Fermata, Inc. Troy Hibbitts Texas Herpetological Society Wallace Rogers TPWD Private Lands Advisory Board Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Working Groups Aquatic Working Group Gary Garrett (chair) Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Paul Hammerschmidt (chair) Texas Parks and Wildlife Department 578 Carrie Thompson U.S. -

Connector Guide for Webex

Oracle® Identity Manager Connector Guide for WebEx Release 11.1.1 E79077-02 May 2020 Oracle Identity Manager Connector Guide for WebEx, Release 11.1.1 E79077-02 Copyright © 2016, 2020, Oracle and/or its affiliates. Primary Author: Gowri GR Contributors: Mike Howlett This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, then the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs (including any operating system, integrated software, any programs embedded, installed or activated on delivered hardware, and modifications of such programs) and Oracle computer documentation or other Oracle data delivered to or accessed by U.S. Government end users are "commercial computer software" or “commercial computer software documentation” -

Gong Shamal Mp3, Flac, Wma

Gong Shamal mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Shamal Country: Netherlands Released: 1975 Style: Fusion, Jazz-Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1746 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1100 mb WMA version RAR size: 1677 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 778 Other Formats: MP4 MP2 AAC MPC TTA AU AUD Tracklist Hide Credits Wingful Of Eyes A1 8:19 Electric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar – Steve HillageWritten-By – Howlett* Chandra A2 7:16 Lyrics By – Howlett*Music By – Lemoine*Violin – Jorge Pinchevsky Bambooji A3 Electric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar – Steve HillageViolin – Jorge PinchevskyVocals – Miquette 5:21 GiraudyWritten-By – Malherbe* Cat In Clark's Shoes B1 7:45 Violin – Jorge PinchevskyWritten-By – Malherbe*, Howlett*, Lemoine* Mandrake B2 5:07 Written-By – Moerlen* Shamal B3 Violin – Jorge PinchevskyVocals – Sandy ColleyWritten-By – Malherbe*, Howlett*, Bauer*, 8:58 Lemoine*, Moerlen* Credits Artwork – Mustard Bass Guitar, Vocals – Mike Howlett Design [Cover], Photography By – Clive Arrowsmith Drums, Vibraphone, Bells [Tubular] – Pierre Moerlen Engineer – Ben King Engineer [Mix] – Rick Curtain Lighting [Lights] – Wiz De Courbe Marimba, Percussion [Assorted], Glockenspiel, Xylophone, Gong – Mireille Bauer Piano, Organ, Synthesizer [Mini-moog] – Patrice Lemoine Producer – Nick Mason Technician [Live Sounds] – Cedric Beatty Technician [Stage Sound] – George McQuade Tenor Saxophone, Soprano Saxophone, Flute [Bamboo, C&g Flutes], Gong – Didier "Bloom" Malherbe* Notes Recorded at Basing Street Studios, London and at Olympic Studios, London Mixed at -

First International Conference of the ACADPROG Network Dedicated to Progressive Rock

CALL FOR PAPER For the First International Conference of the ACADPROG Network dedicated to progressive rock Introduction to ACADPROG Network Thanks to the initiative of Allan Moore, many researchers from various horizons have decided to create ACADPROG in 2011. From the beginning, this international network has decided to use their various fields of competences to study all the aspects of progressive rock, a style of music born at the end of the 1960s. In order for their work to acquire a certain visibility and for this new field of research to find a place within the field of popular music studies, ACADPROG is organising its first international conference on the 10th, 11th and 12th december 2014 in Dijon (France), thanks to the support of the University of Burgundy, the GC and CIMEOS laboratories and some institutional partners. Have you said prog rock ? From a musical point of view, this trend is characterised by references to classical music (from the baroque to contemporary music) as well as jazz music, through its taste for long instrumental developments and its marked interest for sound innovation. Beyond the sound aspect, this music is also inspired by literature (especially heroic fantasy and science fiction) for its lyrics and illustrations, while it also included some theatricality in its performances. While most of the groups who new international fame in the middle of the 1970s originated from Great Britain (Pink Floyd, Soft Machine, Genesis, King Crimson, Yes, ELP, Van Der Graff Generator, Jethro Tull, Roxy Music, Hatfied and the North, Supertramp, UK, Marillon etc.), a few French, Italian, North American and Japanese bands also had an international career. -

The Record Producer As Nexus

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Howlett, Mike (2012) The record producer as nexus. Journal on the Art of Record Production, 2012(6), pp. 1-6. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/56743/ c Copyright 2012 Art of Record Production Creative Commons: Attribution 2.5 License: Creative Commons: Attribution 2.5 Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// arpjournal.com/ theme/ conference-paper/ The record producer as a nexus Mike Howlett Queensland University of Technology In this paper I propose the concept of the record producer as a “nexus” between the creative inspiration of the artist, the technology of the recording studio, and the commercial aspirations of the record company. In much of the published discussion of the producer’s role the term “mediator” is preferred, however, I argue that this term describes a technical process of transfer between media, such as from a performance to a recording as mediated by the microphones, the mixer and the recording medium. Tom Porcello says, “because microphones do not ‘hear’ in the same way as ears, the sound engineer must … mediate between the interpretive and performance habits of the conductor and the musicians on one hand, and the acoustic properties of the microphones and the (psycho)acoustics of the ear on the other” (2005). -

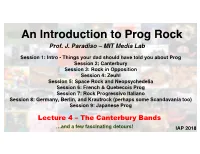

An Introduction to Prog Rock Prof

An Introduction to Prog Rock Prof. J. Paradiso – MIT Media Lab Session 1: Intro - Things your dad should have told you about Prog Session 2; Canterbury Session 3: Rock in Opposition Session 4: Zeuhl Session 5: Space Rock and Neopsychedelia Session 6: French & Quebecois Prog Session 7: Rock Progressivo Italiano Session 8: Germany, Berlin, and Krautrock (perhaps some Scandavania too) Session 9: Japanese Prog Lecture 4 – The Canterbury Bands …and a few fascinating detours! IAP 2018 The City of Canterbury London Up Here An amazingly creative bunch of emerging musicians hung out at Robert Wyatt’s House & environs in the mid 60s Memories Brian & Hugh Hopper, Richard Sinclair, Kevin Ayers formed The Wilde Flowers in the early 1960s – Daevid Allen, David Sinclair, Richard Coughlin, etc. in the mix too Leading to Soft Machine, Caravan, Gong, and Kevin Ayers solo career Enter Soft Machine! Robert Wyatt, Hugh Hopper, Mike Ratledge (Daevid Allen, Kevin Ayers) Jimi was their colleague, friend, and fan He gave them their sound… We Did It Again Early Soft Machine 1968 1969 Why Are We Sleeping? As Long as he Lies Perfectly Still Hung out and toured with Jimi Hendrix Fuzzbox and pedals on organ are iconic in Canterbury Music Very intense live band Hope for Happiness (Live @ Middle Earth Club) - 1967 Live in France - 1968 Kevin Ayers splits for his solo career 1969 1970 1972 1974 Rheinhardt And Geraldine / Colores Para Dolores (1970) The Confessions Of Doctor Dream: Irreversible Neural Damage (1974) Becoming a (psychedelic) Jazz Band 1970 1971 1972 Last -

Smash Hits Volume 48

PAULWELLER ROBERT PALMER GARY NUNAN in colour BAD MANNERS ROCKPILE -*' October 2-15 1980 Vol. 2 No. 20 irchestral Manoeuvres in The I GOT YOU Split Enz 10 THE QUARTER MOON The VIPs 10 I TOLD YOU SO The Tourists 11 MY OLD PIANO Diana Ross 17 IF YOU'RE LOOKING FOR A WAY OUT Odyssey 17 D.I.S.C.O. Ottawan 23 THREE LITTLE BIRDS Bob Marley & The Wailers ..26 AMIGO Black Slate 26 Enola Gay YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC/DC 31 By Orchestral Manoeuvres In the Dark on Dindisc Recor" ANOTHER ONE BITES THE DUST Queen 33 WHITE RIOT The Clash 35 Enola Gay You should have stayed at home yesterday SPECIAL BREW Bad Manners 38 Aha, words can't describe TEMPORARY SECRETARY Paul McCartney 41 The feeling and the way you lied KILLER ON THE LOOSE Thin Lizzy 47 These games you play They're gonna end in tears someday Aha, Enola Gay GARYNUMAN: Photo Feature 4/5/6 It shouldn't ever have to end this way ROCKPILE: Feature 18/19 It's 8.15 PAUL WELLER: Colour Poster 24/25 And that's the time that it's always been BAD MANNERS: Feature 36/37/38 We got your message on the radio Conditions normal and you're coming home ROBERT PALMER: Colour Photo 48 Enola Gay Is mother proud of little boy today? CARTOON 9 Aha, this kiss you give It's never ever gonna fade away NEWSDESK 9 BITZ 12/13/14 Enola Gay INDEPENDENT BITZ 20 It shouldn't ever have to end this way Aha, Enola Gay KORG SYNTHESIZER COMPETITION 21 It shouldn't fade in our dreams away DISCO 23 It's 8.15 CROSSWORD 27 And that's the time that it's always been REVIEWS 28/29 We got your message on the radio Conditions normal and you're coming home FACT IS 30 PENPALS 30 Enola Gay STAR TEASER 32 Is mother proud of little boy today? Aha, this kiss you give COMPETITION 40 It's never ever gonna fade away LETTERS 43/44 Words and music by Andy McCluskey GIGZ 46 Reproduced py permission Dinsong Ltd. -

Gong Zero to Infinity Mp3, Flac, Wma

Gong Zero To Infinity mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Rock Album: Zero To Infinity Country: UK Released: 2000 Style: Fusion, Psychedelic Rock, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1864 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1120 mb WMA version RAR size: 1541 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 172 Other Formats: MP2 APE AU MOD VOX AC3 AUD Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Foolfare 0:42 2 Magdalene 3:57 The Invisible Temple 3 11:35 Organ, Drone – Theo Travis 4 Zeroid 6:08 Wise Man In Your Heart 5 8:03 Vocals, Keyboards – Mark Robson 6 The Mad Monk 3:24 7 Yoni On Mars 6:07 8 Damaged Man 5:13 Bodilingus 9 Electric Guitar – Mike HowlettElectronics – Daevid Allen, Theo TravisVoice [Telephone 4:02 Reception] – Toby Robinson* 10 Tali's Song 6:25 11 Infinitea 7:48 Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Universal M & L, UK Phonographic Copyright (p) – Snapper Music Copyright (c) – Snapper Music Recorded At – Moat Studio Mastered At – Country Masters Credits Artwork – Daevid Allen Bass – Mike Howlett Design – Catarina Tost, Peter Hartl Drums, Percussion – Chris Taylor Duduk, Alto Saxophone, Flute [Bamboo] – Didier Malherbe Engineer – Toby Robinson* Guitar [Glissando, Lead], Vocals, Piano – Daevid Allen Lyrics By – Daevid Allen (tracks: 2, 4 to 6, 8 to 10), Gilli Smyth (tracks: 3, 4, 7) Mastered By – Denis Blackham Music By – Taylor* (tracks: 2, 3, 6, 8, 9, 11), Allen* (tracks: 2 to 6, 8 to11), Malherbe* (tracks: 2, 3), Smyth* (tracks: 3, 4, 7, 11), Howlett* (tracks: 2 to 6, 8, 9, 11), Moerlen* (tracks: 5), Travis* (tracks: 3, 6 to 9, 11) Producer – Gong, Mike Howlett Tenor Saxophone, Soprano Saxophone, Flute, Keyboards, Sampler – Theo Travis Vocals [Voicewhisper, Horsewhisper, Birdsong] – Gilli Smyth Notes Recorded at Moat Studios London between the Full Moons of Sept/Oct 1999.