Place and Position in Theatre Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amol and Chitra Palekar

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Interview of Amol and ChitraPalekar FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYASHODHSANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY Recorded on 1st. July, 1982 NatyaBhavan EE 8, Sector 2, Salt Lake, Kolkata 700091/ Call 033 23217667 visit us at http://www.natyashodh.org https://sites.google.com/view/nssheritagelibrary/home (Amol Palekar&ChitraPalekar came a little late and joined the discussionregarding the scope of theatre and the different forms a playwright tries to explore.) ChitraPalekar It is not that you cannot do a thing. You can do anything, you can do anything. It is not the point. The point is that the basic advantage that cinema has over theatre, the whole mass of audience, you know, all those eight hundred or nine hundred people he can put them to a close-up. This tableau we still see in theatre sitting as a design in a particular frame but here you can break that frame, you can go closer and he can focus your attention on just a little point here and a gesture here, and a gesture there and you know, on stage you will have to show with a torch yet it won’t be visible. Amol Palekar The point is …..Obviously two points come to my mind. First and foremost, suppose you are able to do it, and you are able to hold the audience then why not. The question is – yes, you do it for two hours, just keep one tableau and somebody the off sound is there. If that can hold then I think it will be a perfect valid theatre, why not? Bimal Lath Could it be that we can make 10 plays the same way? Amol Palekar Yes, why not? In fact I think on this issue I will say something which will immediately start a big fight so I will purposely started not for the sake of fight but because I believe in it also. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Badal Sircar

Badal Sircar Scripting a Movement Shayoni Mitra The ultimate answer [...] is not for a city group to prepare plays for and about the working people. The working people—the factory workers, the peasants, the landless laborers—will have to make and perform their own plays. [...] This process of course, can become widespread only when the socio-economic movement for emancipation of the working class has also spread widely. When that happens the Third Theatre (in the context I have used it) will no longer have a separate function, but will merge with a transformed First Theatre. —Badal Sircar, 23 November 1981 (1982:58) It is impossible to discuss the history of modern Indian theatre and not en- counter the name of Badal Sircar. Yet one seldom hears his current work talked of in the present. How is it that one of the greatest names, associated with an exemplary body of dramatic work, gets so easily lost in a haze of present-day ignorance? While much of his previous work is reverentially can- onized, his present contributions are less well known and seldom acknowl- edged. It was this slippage I set out to examine. I expected to find an ailing man reminiscing of past glories. I was warned that I might find a cynical per- son, an incorrigible skeptic weary of the world. Instead, I encountered an in- domitable spirit walking along his life path looking resolutely ahead. A kind old man who drew me a map to his house and saved tea for me in a thermos. A theatre person extraordinaire recounting his latest workshop in Laos, devis- ing how to return as soon as possible. -

MA BENGALI SYLLABUS 2015-2020 Department Of

M.A. BENGALI SYLLABUS 2015-2020 Department of Bengali, Bhasa Bhavana Visva Bharati, Santiniketan Total No- 800 Total Course No- 16 Marks of Per Course- 50 SEMESTER- 1 Objective : To impart knowledge and to enable the understanding of the nuances of the Bengali literature in the social, cultural and political context Outcome: i) Mastery over Bengali Literature in the social, cultural and political context ii) Generate employability Course- I History of Bengali Literature (‘Charyapad’ to Pre-Fort William period) An analysis of the literature in the social, cultural and political context The Background of Bengali Literature: Unit-1 Anthologies of 10-12th century poetry and Joydev: Gathasaptashati, Prakitpoingal, Suvasito Ratnakosh Bengali Literature of 10-15thcentury: Charyapad, Shrikrishnakirtan Literature by Translation: Krittibas, Maladhar Basu Mangalkavya: Biprodas Pipilai Baishnava Literature: Bidyapati, Chandidas Unit-2 Bengali Literature of 16-17th century Literature on Biography: Brindabandas, Lochandas, Jayananda, Krishnadas Kabiraj Baishnava Literature: Gayanadas, Balaramdas, Gobindadas Mangalkabya: Ketakadas, Mukunda Chakraborty, Rupram Chakraborty Ballad: Maymansinghagitika Literature by Translation: Literature of Arakan Court, Kashiram Das [This Unit corresponds with the Syllabus of WBCS Paper I Section B a)b)c) ] Unit-3 Bengali Literature of 18th century Mangalkavya: Ghanaram Chakraborty, Bharatchandra Nath Literature Shakta Poetry: Ramprasad, Kamalakanta Collection of Poetry: Khanadagitchintamani, Padakalpataru, Padamritasamudra -

A Complete Profile of Rangroop

MMMAJOR PRODUCTIONS OF RANGRANG----ROOPROOP SINCE THE INCEPTION: Total Name Of The Year No. Of Drama By Directed By Production Shows 1969-70 Michhil 12 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee 1972-73 Akay Akay Sunya 9 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee 1979-80 Kanthaswar 151 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee Sanskrit play: Banabhatta; Adaptation : 1982-83 Kadambari 50 Goutam Mukherjee Dr. K.K. Chakraborty Story: Subodh Ghosh 1984-85 Andhkarer Rang 62 Script: Sima Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee Story: O’Henry Do. Prahasan 62 Script: K.K. Chakraborty Goutam Mukherjee Story: O’Henry 1987-88 Clown 110 Script: K.K. Chakraborty Goutam Mukherjee 1988-89 Bikalpa 74 Sima Mukhopadhyay Goutam Mukherjee Dwijen Banerjee & 1991-92 Bhanga Boned 130 Sima Mukhopadhyay Saonli Mitra 1992-93 Tringsha Shatabdi 5 Badal Sarkar Kaliprosad Ghosh 1993-94 Boli 11 Tripti Mitra Sima Mukhopadhyay 1994-95 Je Jan Achhey 187 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay Majhkhane Sima Mukhopadhyay 1996-97 24 Abanindranath Tagore Aalor Phulki & K K Mukhopadhyay Panu Santi Sima Mukhopadhyay Krishna Kishore 1998-99 53 Cheyechhilo (Story: Ramanath Roy) Mukhopadhyay 1999- Aaborto 27 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay 2000 2000-01 Sunyapat 34 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay Drama: Olwen Wymark 2002-03 Khnuje Nao 37 Adaptation: Swatilekha Sengupta Rudraprasad Sengupta Je Jan Achhey 2003-04 Majhkhane 32 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay (Revive) 2004-05 Sesh Raksha 38 Rabindranath Tagore Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay 2005-06 He Mor Debota 10 (Story: Deborshee Sima Mukhopadhyay Saroghee) -

EVAM INDRAJIT by Badal Sircar

EVAM INDRAJIT By Badal Sircar (PART – 1) ABOUT THE AUTHOR Indroduction Badal Sircar (15 July 1925–13 May 2011), also known as Badal Sarkar, was an influential Indian dramatist and theatre director. He is mostly known for his anti-establishment plays during the Naxalite movement in the 1970s. He took theatre out of the proscenium and into public arena, when he founded his own theatre company, Shatabdi in 1976. He wrote more than fifty plays of which Ebong Indrajit, Basi Khabar, and Saari Raat are well known literary pieces. As a theorist and philosopher of Indian theatre, Sircar opened up the discourse to include concerns with democratic human interaction and a search for a more just and equitable society. As a mentor and teacher, he travelled widely across the country holding workshops which had a deep impact on hundreds of theatre workers, including some major directors. Education Sircar was initially schooled at the Scottish Church Collegiate School, Kolkata. After transferring from the Scottish Church College, he studied civil engineering at the Bengal Engineering College (now IIEST), Shibpur, Howrah then affiliated with the University of Calcutta. In 1992, he finished his Master of Arts degree in comparative literature from the Jadavpur University in Kolkata. Career While Sircar was working as a town planner in India, England and Nigeria, he entered theatre as an actor, moved to direction, but soon started writing plays, starting with comedies. He experimented with theatrical environments such as stage, costumes and presentation and established a new genre of theatre called "Third Theatre". In Third Theatre approach, he created a direct communication with audience and emphasised on expressionist acting along with realism. -

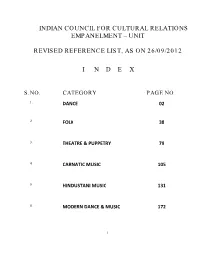

Unit Revised Reference List

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT – UNIT REVISED REFERENCE LIST, AS ON 26/09/2012 I N D E X S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. DANCE 02 2. FOLK 38 3. THEATRE & PUPPETRY 79 4. CARNATIC MUSIC 105 5. HINDUSTANI MUSIC 131 6. MODERN DANCE & MUSIC 172 1 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMEMT SECTION REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE - AS ON 26/09/2012 S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. BHARATANATYAM 3 – 11 2. CHHAU 12 – 13 3. KATHAK 14 – 19 4. KATHAKALI 20 – 21 5. KRISHNANATTAM 22 6. KUCHIPUDI 23 – 25 7. KUDIYATTAM 26 8. MANIPURI 27 – 28 9. MOHINIATTAM 29 – 30 10. ODISSI 31 – 35 11. SATTRIYA 36 12. YAKSHAGANA 37 2 REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE AS ON 26/09/2012 BHARATANATYAM OUTSTANDING 1. Ananda Shankar Jayant (Also Kuchipudi) (Up) 2007 2. Bali Vyjayantimala 3. Bhide Sucheta 4. Chandershekar C.V. 03.05.1998 5. Chandran Geeta (NCR) 28.10.1994 (Up) August 2005 6. Devi Rita 7. Dhananjayan V.P. & Shanta 8. Eshwar Jayalakshmi (Up) 28.10.1994 9. Govind (Gopalan) Priyadarshini 03.05.1998 10. Kamala (Migrated) 11. Krishnamurthy Yamini 12. Malini Hema 13. Mansingh Sonal (Also Odissi) 14. Narasimhachari & Vasanthalakshmi 03.05.1998 15. Narayanan Kalanidhi 16. Pratibha Prahlad (Approved by D.G March 2004) Bangaluru 17. Raghupathy Sudharani 18. Samson Leela 19. Sarabhai Mallika (Up) 28.10.1994 20. Sarabhai Mrinalini 21. Saroja M K 22. Sarukkai Malavika 23. Sathyanarayanan Urmila (Chennai) 28.10.94 (Up)3.05.1998 24. Sehgal Kiran (Also Odissi) 25. Srinivasan Kanaka 26. Subramanyam Padma 27. -

M.P.A (Theatre Arts)

'. Code No: N-35 ENTRANCE EXAMINATION, 2017 M.P.A (Theatre Arts) MAX.MARKS:50 DATE: 04 -06-2017 TIME: 10:00 AM Duration 2 hours HALL TICKET NO: __________ Instructions: i) Write your Hall Ticket Number in OMR Answer Sheet given to you. Also write the Hall Ticket Number in the space provided above. ii) There is negative marking. Each wrong answer carries-O.33mark. iii) Answers are to be marked on OMR answer sheet following the instructions provided there upon. iv) Hand over the OMR answer sheet at the end of the examination to the Invigilator. v) No additional sheets will be provided. Rough work can be done in the question paper itself/ space provided at the end of the booklet. 1. The author of the play "Nagamandala" is ______ A) Chandrashekhara Kambar C) Bhartendu Harishchandra B) B.Y Karant D) Girish Karnad 2. Guru Birju Maharaj is an exponent of the form _____ A) Kathakali C) Kathak B) Kuchipudi D) Odissi 3. Founder of the theatre group 'Kalakshetra Manipur' is. _______ A) Ratan Thiyam C) Lokendra Arambam, B) Heisnam Kanhailal, D) S. Thanilleirna 1 '. 4. World theatre day is celebrated on ________ A) December 25 C) March 27 B) November 14 D) January 26 5. Rabindranath Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize in the field of______ _ A) Architecture C) Sports B) Sculpture D) Literature 6. The director of the play "Charan Das Chor" of Nay a Theatre group is ______ A) Utpal Dutt C) Ram Gopal Bajaj B) Habib Tanvir, D) Badal Sarkar 7. 'Sopanam,' the theatre wing of Bhasabharati, the Centre for Performing Arts founded by ______ A) Deepan Shivaraman C) Ratan Thiyam B) C RJambe D) Kavalam Narayana Panikkar 8. -

Report of the Joint Committee on the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016

LOK SABHA REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE CITIZENSHIP (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2016 (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI January, 2019/PAUSHA 1940(Saka) 1 LOK SABHA REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE CITIZENSHIP (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2016 (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) PRESENTED TO LOK SABHA ON 7 JANUARY, 2019 LAID IN RAJYA SABHA ON 7 JANUARY, 2019 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT 2 NEW DELHI January, 2019/PAUSHA 1940(Saka) CONTENTS Page Nos. COMPOSITION OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE (I) INTRODUCTION (iii) REPORT 1-77 BILL AS REPORTED BY JOINT COMMITTEE 78-79 APPENDICES I. Motion in Lok Sabha for Reference of the Bill 80 to the Joint Committee II. Motion in Rajya Sabha for Reference of the Bill 81 to the Joint Committee III. Motion regarding Extension of Time 82 - 82A IV. Notes of Dissent 83 - 127 V. Minutes of the Sittings of the Joint Committee 128 - 190 VI. List of Stakeholders/Organisations/Associations/ 191 - 433 Individuals from whom Memoranda were received in response to the Press Communique issued on 17.09.2016. VII. List of Stakeholders/Public representatives from 434 - 435 whom Memoranda were received through various other sources viz. Ministry of Home Affairs, Prime Minister's Office, President's Secretariat etc. VIII. List of Non-official witnesses who tendered oral 436 - 440 evidence before the Committee 3 COMPOSITION OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE CITIZENSHIP (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2016 *Shri Rajendra Agrawal - CHAIRPERSON MEMBERS Lok Sabha 2. Shri Ramen Deka 3. Shri Pralhad Venkatesh Joshi 4. Shri Kamakhya Prasad Tasa 5. Shri Gopal Chinayya Shetty 6. Shri Om Birla 7. -

Indian Council for Cultural Relations Empanelment of Artistes

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT OF ARTISTES REVISED REFERENCE LIST AS ON 26/09/2012 I N D E X S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. DANCE 02 2. FOLK 38 3. THEATRE & PUPPETRY 79 4. CARNATIC MUSIC 105 5. HINDUSTANI MUSIC 131 6. MODERN DANCE & MUSIC 172 1 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMEMT SECTION REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE - AS ON 26/09/2012 S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. BHARATANATYAM 3 – 11 2. CHHAU 12 – 13 3. KATHAK 14 – 19 4. KATHAKALI 20 – 21 5. KRISHNANATTAM 22 6. KUCHIPUDI 23 – 25 7. KUDIYATTAM 26 8. MANIPURI 27 – 28 9. MOHINIATTAM 29 – 30 10. ODISSI 31 – 35 11. SATTRIYA 36 12. YAKSHAGANA 37 2 REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE AS ON 26/09/2012 BHARATANATYAM OUTSTANDING 1. Ananda Shankar Jayant (Also Kuchipudi) 2. Bali Vyjayantimala 3. Bhide Sucheta 4. Chandershekar C.V. 5. Chandran Geeta (NCR) 6. Devi Rita 7. Dhananjayan V.P. & Shanta 8. Eshwar Jayalakshmi 9. Govind (Gopalan) Priyadarshini 10. Kamala (Migrated) 11. Krishnamurthy Yamini 12. Malini Hema 13. Mansingh Sonal (Also Odissi) 14. Narasimhachari & Vasanthalakshmi 15. Narayanan Kalanidhi 16. Pratibha Prahlad (Approved by D.G March 2004) Bangaluru 17. Raghupathy Sudharani 18. Samson Leela 19. Sarabhai Mallika 20. Sarabhai Mrinalini 21. Saroja M K 22. Sarukkai Malavika 23. Sathyanarayanan Urmila (Chennai) 24. Sehgal Kiran (Also Odissi) 25. Srinivasan Kanaka 26. Subramanyam Padma 27. Vaidyanathan Rama (NCR) 28. Valli Alarmel (Spe.) 29. Viswanathan Lakshmi 30. Visweswaran Chitra 3 BHARATANATYAM ESTABLISHED 1. Anjana Anand (Chennai) 2. Ashok Purnima (Bangaluru) 3. Arekar Vaibhav S. (Mumbai) 4. Balasubramaniam Ramesh Uma (Chennai) 5. -

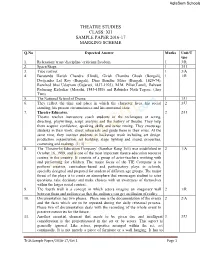

Theatre Studies Class: Xii Sample Paper 2016-17 Marking Scheme

AglaSem Schools THEATRE STUDIES CLASS: XII SAMPLE PAPER 2016-17 MARKING SCHEME Q.No Expected Answer Marks Unit/T ypo 1. Relaxation/ trust/ discipline/ criticism/freedom 1 3/R 2. Space/Stage 1 3/H 3. Type casting 1 3/A 4. Baratendu Harish Chandra (Hindi), Girish Chandra Ghosh (Bengali), 1 1/R Dwijendra Lal Roy (Bengali), Dina Bandhu Mitra (Bengali, 1829-74), Ranchod bhai Udayram (Gujarati, 1837-1923), M.M. Pillai(Tamil), Balvant Padurang Kirloskar (Marathi, 1843-1885) and Rabindra Nath Tagore. (Any Two) 5. The National School of Drama 1 1/U 6. They reflect the time and place in which the character lives, his social 2 3/U standing, his present circumstances and his emotional state. 7. Theatre Educator. 2 2/H Theatre teacher instructors coach students in the techniques of acting, directing, playwriting, script analysis and the history of theatre. They help them acquire confidence, speaking skills and sense timing. They encourage students in their work, direct rehearsals and guide them in their roles. At the same time, they instruct students in backstage work including set design, production organization, set building, stage lighting and sound, properties, costuming and makeup. (1+1) 8. The ‘Theatre-In-Education Company’ (Sanskar Rang Toli) was established in 2 1/A October 16, 1989, and is one of the most important theatre education resource centres in the country. It consists of a group of actor-teachers working with and performing for children. The major focus of the TIE Company is to perform creative, curriculum-based and participatory plays in schools, specially designed and prepared for student of different age groups. -

List of Files Pending at Applicant 12440

LIST OF FILES PENDING AT APPLICANT 12440 CA2061700475512 TARAPADA DHALI HARAN 12441 CA2061495569012 KANU DAS BINOD BIHARI 12442 CA1067473147114 GOBINDA DAS SHUDHANSHU 12443 CA2068117104714 PRASANTA MALAKAR LAXMIKANTA 12444 CA2068171385314 KAMALUDDIN MONDAL KAYKOBAD 12445 CA2071428232512 SUSAMA PAL SHYAMA PADA 12446 CA1067566859314 PRADIP MISTRY BHABATOSH 12447 CA2068147942314 ASMITA BOSE JAYDEV 12448 CA2071949372513 NANDA MONDAL SRIDAM 12449 CA2068041504314 LAXMI RANI BHOWMICK BASUDEB 12450 CA2068124707114 MD ALI AJGAR MD HANIF 12451 CA1067928717114 SMARAJIT BISWAS SUDHIR 12452 CA2061510320412 HARIPADA MONDAL KAMAL 12453 CA1067465217714 MRINAL KANTI GHOSH NRIPENDRA CHANDRA 12454 CA2061794426513 MILAN DEURI MAHANANDA 12455 CA1061855481113 AJAY BAG KENA 12456 CA2061672265712 ANARUL MONDAL AZIHAR 12457 CA1061959278113 KARIBUL ISLAM KABIRUL 12458 CA1067749788314 ATIN PAL DHIREN 12459 CA2068083413314 SUBIR MONDAL SUDHIR 12460 CA1068142445114 SUSHANTA BAIRAGYA JIBAN 12461 CA1067161754513 ISLAM SAMAUL KABIR ENAMUL 12462 CA1061638940512 ABDUL ALIM ABDUL 12463 CA1067576939914 AKTAR ALI JULLAUR RAHAMAN 12464 CA2067712325514 BIDHAN SIKDAR BHUBAN 12465 CA2067404636713 BISWAJIT MONDAL ASIT KUMAR 12466 CA2067808438314 RAKESH BHAKTA GOPAL 12467 CA2067362554313 BAPPA MONDAL MALOY 12468 CA2061114246913 BHAKTA MALLICK JIBAN Page 431 LIST OF FILES PENDING AT APPLICANT 12469 CA2067639826714 RITA RANI DAS GOUR MOHAN 12470 CA1067798589114 PRANAB RAY HARAN 12471 CA2067221162513 ANUPAM BISWAS DILIP 12472 CA2068112645714 MUNSUR HABIBULLA SK SAMAD 12473 CA2068102845914