Music As Sound, Music As Archive: Performing Creolization in Trinidad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sitaram Asur, B.E., M.Sc. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Prof. Srinivasan Parthasarathy, Adviser Prof. Gagan Agrawal Adviser Prof. P. Sadayappan Graduate Program in Computer Science and Engineering c Copyright by Sitaram Asur 2009 ABSTRACT Data originating from many different real-world domains can be represented mean- ingfully as interaction networks. Examples abound, ranging from gene expression networks to social networks, and from the World Wide Web to protein-protein inter- action networks. The study of these complex networks can result in the discovery of meaningful patterns and can potentially afford insight into the structure, properties and behavior of these networks. Hence, there is a need to design suitable algorithms to extract or infer meaningful information from these networks. However, the challenges involved are daunting. First, most of these real-world networks have specific topological constraints that make the task of extracting useful patterns using traditional data mining techniques difficult. Additionally, these networks can be noisy (containing unreliable interac- tions), which makes the process of knowledge discovery difficult. Second, these net- works are usually dynamic in nature. Identifying the portions of the network that are changing, characterizing and modeling the evolution, and inferring or predict- ing future trends are critical challenges that need to be addressed in the context of understanding the evolutionary behavior of such networks. To address these challenges, we propose a framework of algorithms designed to detect, analyze and reason about the structure, behavior and evolution of real-world interaction networks. -

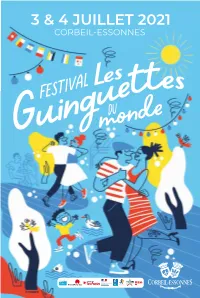

3 & 4 Juillet 2021

3 & 4 JUILLET 2021 CORBEIL-ESSONNES À L’ENTRÉE DU SITE, UNE FÊTE POPULAIRE POUR D’UNE RIVE À L’AUTRE… RE-ENCHANTER NOTRE TERRITOIRE Pourquoi des « guinguettes » ? à établir une relation de dignité Le 3 juillet Le 4 juillet Parce que Corbeil-Essonnes est une avec les personnes auxquelles nous 12h 11h30 ville de tradition populaire qui veut nous adressons. Rappelons ce que le rester. Parce que les guinguettes le mot culture signifie : « les codes, Parade le long Association des étaient des lieux de loisirs ouvriers les normes et les valeurs, les langues, des guinguettes originaires du Portugal situés en bord de rivière et que nous les arts et traditions par lesquels une avons cette chance incroyable d’être personne ou un groupe exprime SAMBATUC Bombos portugais son humanité et les significations Départ du marché, une ville traversée par la Seine et Batucada Bresilienne l’Essonne. qu’il donne à son existence et à son place du Comte Haymont développement ». Le travail culturel 15h Pourquoi « du Monde » ? vers l’entrée du site consiste d’abord à vouloir « faire Parce qu’à Corbeil-Essonnes, 93 Super Raï Band humanité ensemble ». le monde s’est donné rendez-vous, Maghreb brass band 12h & 13h30 108 nationalités s’y côtoient. Notre République se veut fraternelle. 16h15 Aquarela Nous pensons que cela est On ne peut concevoir une humanité une chance. fraternelle sans des personnes libres, Association des Batucada dignes et reconnues comme telles Alors pourquoi une fête des originaires du Portugal dans leur identité culturelle. 15h « guinguettes du monde » Bombos portugais Association Scène à Corbeil-Essonnes ? À travers cette manifestation, 18h Parce que c’est tellement bon de c’est le combat éthique de Et Sonne faire la fête. -

Streams of Civilization: Volume 2

Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press i Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 1 8/7/17 1:24 PM ii Streams of Civilization Volume Two Streams of Civilization, Volume Two Original Authors: Robert G. Clouse and Richard V. Pierard Original copyright © 1980 Mott Media Copyright to the first edition transferred to Christian Liberty Press in 1995 Streams of Civilization, Volume Two, Third Edition Copyright © 2017, 1995 Christian Liberty Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without written permission from the publisher. Brief quota- tions embodied in critical articles or reviews are permitted. Christian Liberty Press 502 West Euclid Avenue Arlington Heights, Illinois 60004-5402 www.christianlibertypress.com Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press Revised and Updated: Garry J. Moes Editors: Eric D. Bristley, Lars R. Johnson, and Michael J. McHugh Reviewers: Dr. Marcus McArthur and Paul Kostelny Layout: Edward J. Shewan Editing: Edward J. Shewan and Eric L. Pfeiffelman Copyediting: Diane C. Olson Cover and Text Design: Bob Fine Graphics: Bob Fine, Edward J. Shewan, and Lars Johnson ISBN 978-1-629820-53-8 (print) 978-1-629820-56-9 (e-Book PDF) Printed in the United States of America Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 2 8/7/17 1:24 PM iii Contents Foreword ................................................................................1 Introduction ...........................................................................9 Chapter 1 European Exploration and Its Motives -

Coopération Culturelle Caribéenne : Construire Une Coopération Autour Du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Anaïs Diné

Coopération culturelle caribéenne : construire une coopération autour du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Anaïs Diné To cite this version: Anaïs Diné. Coopération culturelle caribéenne : construire une coopération autour du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-01730691 HAL Id: dumas-01730691 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01730691 Submitted on 13 Mar 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Sous le sceau de l’Université Bretagne Loire Université Rennes 2 Equipe de recherche ERIMIT Master Langues, cultures étrangères et régionales Les Amériques – Parcours PESO Coopération culturelle caribéenne Construire une coopération autour du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Anaïs DINÉ Sous la direction de : Rodolphe ROBIN Septembre 2017 0 1 REMERCIEMENTS Je tiens à remercier toutes les personnes avec lesquelles j’ai pu échanger et qui m’ont aidé à la rédaction de ce mémoire. Je remercie tout d’abord mon directeur de recherches Rodolphe Robin pour m’avoir accompagné et soutenu depuis mes premières années à l’Université Rennes 2. Je remercie grandement l’Université Rennes 2 et l’Université de Puerto Rico (UPR) pour la formation et toutes les opportunités qu’elles m’ont offertes. -

The Dougla Poetics of Indianness: Negotiating Race and Gender in Trinidad

The dougla poetics of Indianness: Negotiating Race and Gender in Trinidad Keerti Kavyta Raghunandan Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy Centre of Ethnicity and Racism Studies June 2014 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © The University of Leeds, 2014, Keerti Kavyta Raghunandan Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Shirley Anne Tate. Her refreshing serenity and indefatigable spirit often helped combat my nerves. I attribute my on-going interest in learning about new approaches to race, sexuality and gender solely to her. All the ideas in this research came to fruition in my supervision meetings during my master’s degree. Not only has she expanded my intellectual horizons in a multitude of ways, her brilliance and graciousness is simply unsurpassed. There are no words to express my thanks to Dr Robert Vanderbeck for his guidance. He not only steered along the project to completion but his meticulous editing made this more readable and deserves a very special recognition for his patience, understanding, intelligence and sensitive way of commenting on my work. I would like to honour and thank all of my family. My father who was my refuge against many personal storms and who despite facing so many of his own battles, never gave up on mine. -

Celebrating Our Calypso Monarchs 1939- 1980

Celebrating our Calypso Monarchs 1939-1980 T&T History through the eyes of Calypso Early History Trinidad and Tobago as most other Caribbean islands, was colonized by the Europeans. What makes Trinidad’s colonial past unique is that it was colonized by the Spanish and later by the English, with Tobago being occupied by the Dutch, Britain and France several times. Eventually there was a large influx of French immigrants into Trinidad creating a heavy French influence. As a result, the earliest calypso songs were not sung in English but in French-Creole, sometimes called patois. African slaves were brought to Trinidad to work on the sugar plantations and were forbidden to communicate with one another. As a result, they began to sing songs that originated from West African Griot tradition, kaiso (West African kaito), as well as from drumming and stick-fighting songs. The song lyrics were used to make fun of the upper class and the slave owners, and the rhythms of calypso centered on the African drum, which rival groups used to beat out rhythms. Calypso tunes were sung during competitions each year at Carnival, led by chantwells. These characters led masquerade bands in call and response singing. The chantwells eventually became known as calypsonians, and the first calypso record was produced in 1914 by Lovey’s String Band. Calypso music began to move away from the call and response method to more of a ballad style and the lyrics were used to make sometimes humorous, sometimes stinging, social and political commentaries. During the mid and late 1930’s several standout figures in calypso emerged such as Atilla the Hun, Roaring Lion, and Lord Invader and calypso music moved onto the international scene. -

'Governing Sound: the Cultural Politics of Trinidad's Carnival Musics'

H-Caribbean Stuempfle on Guilbault, 'Governing Sound: The Cultural Politics of Trinidad's Carnival Musics' Review published on Monday, February 23, 2009 Jocelyne Guilbault. Governing Sound: The Cultural Politics of Trinidad's Carnival Musics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. Plates, illustrations. xii + 343 pp. $29.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-226-31060-2. Reviewed by Stephen Stuempfle (Indiana University) Published on H-Caribbean (February, 2009) Commissioned by Clare Newstead Contesting Calypso, Soca, and Nationhood in Trinidad Over the past two decades, numerous books have been published on calypso--Trinidad’s pre-Lenten Carnival music. Encompassing a range of literary, musicological, anthropological, and historical perspectives, this scholarship has been particularly strong on the emergence of the modern calypso form around 1900 and its development through Trinidad and Tobago’s independence from Britain in 1962. Jocelyne Guilbault’s new book is a most welcome addition to this literature, given her focus on Carnival music from the postindependence years to the present. An ethnomusicologist, Guilbault previously studied the music of St. Lucia and was the lead author (with Gage Averill, Édouard Benoit, and Gregory Rabess) of an important book on zouk in the Francophone Caribbean,Zouk: World Music in the West Indies (1993). Her ethnographic and musicological skills, along with her knowledge of local and global dimensions of Caribbean music industries, make her well qualified to tackle the complexities of postcolonial calypso and its musical offshoots, including soca (a dance music with a prominent bass line and dense electronic texture), chutney soca (a synthesis of soca and Indo-Trinidadian musical elements), ragga soca (soca influenced by Jamaican dancehall), and rapso (a blend of chanted poetry, calypso, and other musical styles). -

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin To cite this version: Denis-Constant Martin. Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. African Minds, Somerset West, pp.472, 2013, 9781920489823. halshs-00875502 HAL Id: halshs-00875502 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00875502 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin AFRICAN MINDS Published by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West, 7130, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.co.za 2013 African Minds ISBN: 978-1-920489-82-3 The text publication is available as a PDF on www.africanminds.co.za and other websites under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, as long as it is attributed to African Minds and used for noncommercial, educational or public policy purposes. The illustrations are subject to copyright as indicated below. Photograph page iv © Denis-Constant -

Chapter 6 Bacchanal Time

Chapter 6 Bacchanal Time (1) C/U Pages 87-92 Contrasting calypso and soca Based on text Chapter 6 and using Worksheet 6.1, draw a comparison chart for calypso and soca. What differences in values do each type of music emphasize? Below is a chart for the instructor's reference: Calypso Soca • important to preserve musical • tradition has to change to stay alive; conventions legitimate to mix styles • importance of wordplay and stroytelling; • dance and festivity are as important as "oral literature" literature • money is a corrupting influence • need for calypsonians to make a living • mainly music for tent • mainly music for the road (2) S, C/U Fusion of musical styles Chapter 6 lays out various musical styles related to calypso and their influences from other musical styles. Is there any music in the United States that is influenced from another musical style? Use Worksheet 6.2 to name these styles and their sources of influences. Allow students to bring in music of their own. The discussion should be wide open, because all music is influenced by others in some ways. Point out to students that fusion of musical styles is common to all musical traditions. For example, popular styles from the 1960s to the current time are influenced by the Beatles, and music of the Beatles was influenced by, or incorporated, many other styles such as Indian sitar, blues, string ensemble, and brass band music. Another example is that Gershwin's music was influenced by the symphonic literature as well as by jazz. Debussy's music was influenced by the gamelan music he heard, and by ragtime and jazz. -

Music, Politics, and Power in Grenada, West Indies Danielle Sirek University of Windsor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship at UWindsor University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Education Publications Faculty of Education 6-2016 Providing Contexts for Understanding Musical Narratives of Power in the Classroom: Music, Politics, and Power in Grenada, West Indies Danielle Sirek University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.uwindsor.ca/educationpub Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Music Education Commons Recommended Citation Sirek, Danielle. (2016). Providing Contexts for Understanding Musical Narratives of Power in the Classroom: Music, Politics, and Power in Grenada, West Indies. Action, Criticism, & Theory for Music Education, 15 (3), 151-179. http://scholar.uwindsor.ca/educationpub/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty of Education at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education ISSN 1545- 4517 A refereed journal of the Action for Change in Music Education Volume 15 Number 3 June 2016 Essays from the International Symposium on the Sociology of Music Education 2015 Edward McClellan, Guest Editor Vincent C. Bates, Editor Brent C. Talbot, Associate Editor Providing Contexts for Understanding Musical Narratives of Power in the Classroom: Music, Politics, and Power in Grenada, West Indies Danielle Sirek © Danielle Sirek 2016 The content of this article is the sole responsibility of the author. The ACT Journal and the Mayday Group are not liable for any legal actions that may arise involving the article's content, including, but not limited to, copyright infringement. -

University of Florida Thesis Or

FROM INDIAN TO INDO-CREOLE: TASSA DRUMMING, CREOLIZATION, AND INDO- CARIBBEAN NATIONALISM IN TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO By CHRISTOPHER L. BALLENGEE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Christopher L. Ballengee 2 In memory of Krishna Soogrim-Ram 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to numerous individuals for helping this project come to fruition. Thanks first to my committee for their unwavering support. Ken Broadway has been a faithful champion of the music of Trinidad and Tobago, and I am grateful for his encouragement. He is indeed one of the best teachers I have ever had. Silvio dos Santos’ scholarship and professionalism has likewise been an inspiration for my own musical investigations. In times of struggle during research and analysis, I consistently returned to his advice: “What does the music tell you?” Vasudha Narayanan’s insights into the Indian and Hindu experience in the Americas imparted in me an awareness of the subtleties of common practices and to see that despite claims of wholly recreated traditions, they are “always different.” In my time at the University of Florida, Larry Crook has given me the freedom—perhaps too much at times—to follow my own path, to discover knowledge and meaning on my own terms. Yet, he has also been a mentor, friend, and colleague who I hold in the highest esteem. Special thanks also to Peter Schmidt for inspiring my interest in ethnographic film and whose words of encouragement, support, and congratulations propelled me in no small degree through the early and protracted stages of research. -

Chapter 1 Social, Historical and Cultural Background

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/45260 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Charles, Clarence Title: Calypso music : identity and social influence : the Trinidadian experience Issue Date: 2016-11-22 25 Chapter 1 Social, Historical and Cultural Background Although Caribbean history has been well documented, a perusal of the historical and socio- cultural events peculiar to the island of Trinidad will be necessary in order to satisfy some of the goals of this study. It will serve as a backdrop against which the saga of the calypsonian that unfolded; the various strains of calypso music and related innovations that have emerged; the extravaganza of carnival that developed; and the conflict that accompanied these events will be pitted. This chapter facilitates such endeavor. From its discovery in 1498 up until 1796 Trinidad had been a part of the Spanish Empire. Errol Hill (1976) has reported that around 1783, however, French speaking planters from the northern Caribbean islands of Santo Domingo (present day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Martinique, Guadeloupe, Dominica, St. Lucia and Grenada accepted an invitation extended to Catholics by King Charles III via the Cedula of Population to settle there. They brought with them their retinue of African slaves, their Patois French dialect, and their principal form of entertainment, street masquerading (p. 54-86). Out of a total population of 17,700 in 1789, the Africans numbered 10,000. By Hill’s (1972, 1976) accounts and by the accounts of others, after 1797, during the period of British rule which ended in 1962, the flow of immigrants into Trinidad became more diversified and included people from other British colonies, England, and Venezuela.