Chapter 5 DRAMA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Trevor Morris

TREVOR MORRIS COMPOSER Trevor Morris is one of the most prolific and versatile composers in Hollywood. He has scored music for numerous feature films and won two EMMY awards for outstanding composition for his work in Television. Internationally renowned for his music on The Tudors, The Borgias, Vikings and the hit NBC television series Taken, Trevor is a stylistically and musically inventive soundtrack creator. Trevor’s unique musical voice can be heard on his recent film scores which include The Delicacy, Hunter Killer, Asura, Olympus Has Fallen, London Has Fallen, and Immortals. And further Television compositions including Another Life, Condor, Castlevania, The Pillars oF the Earth for Tony and Ridley Scott, Emerald City and Iron Fist for Marvel Television. Trevor has also worked as a co-producer/ conductor/ orchestrator on films including Black Hawk Down, The Last Samurai, The Ring Two, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Batman Begins and collaborated with Tony and Ridley Scott, Neil Jordan, Luc Besson, Jerry Bruckheimer, Antoine Fuqua, Tarsem Singh Dandwar, as well as composers James Newton Howard and Hans Zimmer. Trevor is also a Concert Conductor, conducting his music in live concert performances around the globe, including Film Music Festivals in Cordoba Spain, Tenerife Spain, Los Angeles, and Krakow Poland where he conducted a 100-piece orchestra and choir for over 12,000 fans. Trevor has been nominated 5 times for the prestigious EMMY awards, and won twice. As well as being nominated at the World Soundtrack Awards in Ghent for the ‘Discovery of the Year ‘composer award for the film Immortals. Trevor is a British/Canadian dual citizen, based in Los Angeles. -

Music Editor

DEL SPIVA MUSIC EDITOR FILM: The Old Guard Studio: Netflix Director: Gena Prince-Bythewood Editor: Terylin A. Shropshire Composer: Volker Bertelmann & Dustin O’Halloran Top Gun Meverick Studio: Paramount Pictures Director: Joseph Kosinsky Editor: Chris Lebenzon Composer: Harold Faltermeyer & Hans Zimmer Just Mercy Studio: Warner Bros Director: Destin Daniel Cretton Editor : Nat Sanders Composer: Joel P West DeadPool 2 Studio: Twentieth Century Fox Director: David Leach Editor : Craig Alpert, Elisabet Ronaldsdóttir Composer: Tyler Bates The Defiant Ones Studio: HBO Director: Allen Hughes Editor : Doug Pray Composer: Atticus Ross Blade Runner 2049 Studio: Alcon entertainment Director: Denis Villenueve Editor : Joe Walker Composer: Johann Johannson Roman J. Israel, Esq. Studio: Sony Director: Dan Gilroy Editor : John Gilroy Composer: James Newton-Howard The Glass Castle Studio: Lionsgate Entertainment Director: Destin Daniel Cretton Editor : Nat Sanders Composer: Joel P West Gold Studio: The Weinstein Company, Black Bear Pictures Director: Stephen Gaghan Editor : Rick Grayson Composer: Daniel Pemberton Shots Fired (TV Series) Studio: Twentieth Century Fox Directors: Gina Prince—Bythewood, Jonathon Demme, Malcom D. Lee, Millicent Shelton, Reggie Bythewood Editors Teri Shropshire, Micky Blythe, Jacques Gravett, Nancy Richardso Composer: Terence Blanchard DEL SPIVA MUSIC EDITOR C oco Studio: Lions Gate Director: RZA Editor : Yon Van Kline Keanu Studio: New Line Director: Peter Atencio Editor : Nicholas Mansour Composer: Steve Jablonsky Saints & Strangers (TV Mini-Series) Studio: Sony/NatGeo Director: Gina Mathews Editor : Colby Parker, Jr. Composer: Lorne Balfe Won, Golden Reel: Best Music Editing, TV Long Form Pete’s Dragon Studio: Disney Director: david Lowery Editor : Lisa Zeno Churgin Deepwater Horizon Studio: Lionsgate Director: Peter Berg Editor : Colby Parker, Jr. -

Nomination Press Release

Outstanding Comedy Series 30 Rock • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Television The Big Bang Theory • CBS • Chuck Lorre Productions, Inc. in association with Warner Tina Fey as Liz Lemon Bros. Television Veep • HBO • Dundee Productions in Curb Your Enthusiasm • HBO • HBO association with HBO Entertainment Entertainment Julia Louis-Dreyfus as Selina Meyer Girls • HBO • Apatow Productions and I am Jenni Konner Productions in association with HBO Entertainment Outstanding Lead Actor In A Modern Family • ABC • Levitan-Lloyd Comedy Series Productions in association with Twentieth The Big Bang Theory • CBS • Chuck Lorre Century Fox Television Productions, Inc. in association with Warner 30 Rock • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Bros. Television Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Jim Parsons as Sheldon Cooper Television Curb Your Enthusiasm • HBO • HBO Veep • HBO • Dundee Productions in Entertainment association with HBO Entertainment Larry David as Himself House Of Lies • Showtime • Showtime Presents, Crescendo Productions, Totally Outstanding Lead Actress In A Commercial Films, Refugee Productions, Comedy Series Matthew Carnahan Circus Products Don Cheadle as Marty Kaan Girls • HBO • Apatow Productions and I am Jenni Konner Productions in association with Louie • FX Networks • Pig Newton, Inc. in HBO Entertainment association with FX Productions Lena Dunham as Hannah Horvath Louis C.K. as Louie Mike & Molly • CBS • Bonanza Productions, 30 Rock • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Inc. in association with Chuck Lorre Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Productions, Inc. and Warner Bros. Television Television Alec Baldwin as Jack Donaghy Melissa McCarthy as Molly Flynn Two And A Half Men • CBS • Chuck Lorre New Girl • FOX • Chernin Entertainment in Productions Inc., The Tannenbaum Company association with Twentieth Century Fox in association with Warner Bros. -

Hrvatski Filmski Ljetopis God

hrvatski filmski ljetopis god. 17 (2011) broj 68, zima 2011. Hrvatski filmski ljetopis utemeljili su 1995. Hrvatsko društvo filmskih kritičara, Hrvatska kinoteka i Filmoteka 16 Utemeljiteljsko uredništvo: Vjekoslav Majcen, Ivo Škrabalo i Hrvoje Turković Časopis je evidentiran u FIAF International Index to Film Periodicals, Web of Science (WoS) i u Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI) Uredništvo / Editorial Board: Nikica Gilić (glavni urednik / editor-in-chief) Krešimir Košutić (novi filmovi i festivali / new films and festivals) Bruno Kragić Jurica Starešinčić Tomislav Šakić (izvršni urednik / managing editor) Hrvoje Turković (odgovorni urednik / supervising editor) Suradnici/Contributors: Ivana Jović (lektorski savjeti / proof-reading) Juraj Kukoč (kronika/chronicles) Sandra Palihnić (prijevod sažetaka / translation of summaries) Duško Popović (bibliografije/bibliographies) Anka Ranić (UDK) Dizajn i priprema za tisak / Design and pre-press: Barbara Blasin Ovitak / Cover: Dubravko Mataković (Kill Bill - Krv do koljena, 2003 i Spiderman, 2004) Nakladnik/Publisher: Hrvatski filmski savez / Croatian Film Association Za nakladnika / Publishing Manager: Vera Robić-Škarica ([email protected]) Tisak / Printed By: Tiskara C.B. Print, Samobor Adresa/Contact: Hrvatski filmski savez (za Hrvatski filmski ljetopis), HR-10000 Zagreb, Tuškanac 1 Tajnica redakcije: Vanja Hraste ([email protected]) telefon/phone: (385) 01 / 4848771 telefaks/fax: (385) 01 / 4848764 e-mail uredništva: [email protected] / [email protected], [email protected] www.hfs.hr/ljetopis Izlazi tromjesečno u nakladi od 1000 primjeraka Cijena: 50 kn / Godišnja pretplata: 150 kn Žiroračun: Zagrebačka banka, 2360000-1101556872, Hrvatski filmski savez (s naznakom “za Hrvatski filmski ljetopis”) Hrvatski filmski ljetopis is published quarterly by Croatian Film Association Subscription abroad: 60 € / Account: 2100058638/070 S.W.I.F.T. -

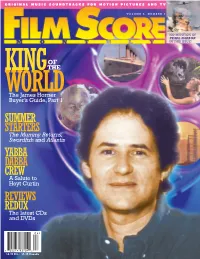

Summer Starters Yabba Dabba Crew Reviews Redux

v6n4cov 5/24/01 5:12 PM Page c1 ORIGINAL MUSIC SOUNDTRACKS FOR MOTION PICTURES AND TV VOLUME 6, NUMBER 4 NO MENTION OF PEARL HARBOR IN THIS ISSUE! OF KING THE WORLDThe James Horner Buyer’s Guide, Part 1 SUMMER STARTERS The Mummy Returns, Swordfish and Atlantis YABBA DABBA CREW A Salute to Hoyt Curtin REVIEWS REDUX The latest CDs and DVDs 04> 7225274 93704 $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada v6n4cov 5/24/01 5:15 PM Page c2 FILM & TV MUSIC SERIES 2001 If you contribute in any way to the film music process, CONTACT: our four Film & TV Music Special Issues provide a unique marketing opportunity for your talent, product or service Los Angeles throughout the year. Judi Pulver [email protected] (323) 525-2026 Film & TV Music Special Issue August 21, 2001 New York Features Calling Emmy,® a complete round-up of music nominations, John Troyan Who Scores PrimeTime and upcoming fall films by distributor, [email protected] director and music credits. (646) 654-5624 Space Deadline: August 1 Materials Deadline: August 8 United Kingdom John Kania Film & TV Music Update: [email protected] November 6, 2001 (44-207) 822-8353 Our year-end wrap on the state of the industry featuring upcoming holiday blockbusters by distributor, director and music credits. director and music credits. Space Deadline: October 19 Materials Deadline: October 25 Dates subject to change. www.hollywoodreporter.com CONTENTS APRIL/MAY 2001 cover story departments 24 King of the World 2 Editorial They said it would never happen—but here it is! Backstage With Six FSM begins another massive Buyers Guide series, Groovy Guys. -

Academy Invites 928 to Membership

MEDIA CONTACT [email protected] June 25, 2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ACADEMY INVITES 928 TO MEMBERSHIP LOS ANGELES, CA – The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is extending invitations to join the organization to 928 artists and executives who have distinguished themselves by their contributions to theatrical motion pictures. Those who accept the invitations will be the only additions to the Academy’s membership in 2018. Ten individuals (noted by an asterisk) have been invited to join the Academy by multiple branches. These individuals must select one branch upon accepting membership. New members will be welcomed into the Academy at invitation-only receptions in the fall. The 2018 invitees are: Actors Hiam Abbass – “Blade Runner 2049,” “The Visitor” Damián Alcázar – “The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian,” “El Crimen del Padre Amaro” Naveen Andrews – “Mighty Joe Young,” “The English Patient” Gemma Arterton – “Their Finest,” “Quantum of Solace” Zawe Ashton – “Nocturnal Animals,” “Blitz” Eileen Atkins – “Gosford Park,” “Cold Mountain” Hank Azaria – “Anastasia,” “The Birdcage” Doona Bae – “Cloud Atlas,” “The Host” Christine Baranski – “Miss Sloane,” “Mamma Mia!” Carlos Bardem – “Assassin’s Creed,” “Che” Irene Bedard – “Smoke Signals,” “Pocahontas” Bill Bellamy – “Any Given Sunday,” “love jones” Haley Bennett – “Thank You for Your Service,” “The Girl on the Train” Tammy Blanchard – “Into the Woods,” “Moneyball” Sofia Boutella – “The Mummy,” “Atomic Blonde” Diana Bracho – “A Ti Te Queria Encontrar,” “Y Tu Mamá También” Alice -

Kingsbane Playlist PART ONE 1. Hawthorne Abendsen – the Man In

Kingsbane Playlist PART ONE 1. Hawthorne Abendsen – The Man in the High Castle – Dominic Lewis 2. Rise Up – Winter’s Tale – Hans Zimmer, Rupert Gregson-Williams 3. Ham Wants Jane – Jane Got a Gun – Lisa Gerrard, Marcello De Francisci 4. Descending – The Handmaid’s Tale – Adam Taylor 5. Eptesicus – Batman Begins – James Newton Howard, Hans Zimmer 6. You’re Carrying His Child – The Huntsman: Winter’s War – James Newton Howard 7. Death Beneath the Horns – Da Vinci’s Demons – Bear McCreary 8. I’m Scared – The Mountain Between Us – Ramin Djawadi 9. A Bright Red Flash – 10 Cloverfield Lane – Bear McCreary 10. The Seer Gives Lagertha a Prophecy – The Vikings – Trevor Morris 11. Touch Nothing Else – Murder on the Orient Express – Patrick Doyle 12. Beneath the Ice – The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim – Jeremy Soule 13. The Downfall – The Crown – Lorne Balfe, Rupert Gregson-Williams 14. The King of the Golden Hall – Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers – Howard Shore 15. Bounden Duty – The Crown – Lorne Balfe, Rupert Gregson-Williams 16. The Necklace – The Man in the High Castle – Dominic Lewis, Henry Jackman 17. Beyond the Hills – Logan – Marco Beltrami PART TWO 1. The Tide – Dunkirk – Hans Zimmer 2. See You for What You Are – Game of Thrones – Ramin Djawadi 3. Drifting in the Dark – The Cloverfield Paradox – Bear McCreary 4. Ofglen and Offred – The Handmaid’s Tale – Adam Taylor 5. The Letter – The Crown – Rupert Gregson-Williams 6. NJ Mart – World War Z – Marco Beltrami 7. The Mole – Dunkirk – Hans Zimmer 8. Little Deceptions – Penny Dreadful – Abel Korzeniowski 9. -

Furyborn Playlist PART ONE 1. the Children – Game of Thrones

Furyborn Playlist PART ONE 1. The Children – Game of Thrones – Ramin Djawadi 2. Resurrection – The Passion of the Christ – John Debney & Lisbeth Scott 3. Immolation – Angels & Demons – Hans Zimmer & Nick Glennie-Smith 4. Ragnar Says Goodbye to Gyda – Vikings – Trevor Morris 5. L’Esprit des Gabriel – The Da Vinci Code – Hans Zimmer 6. Needle – Game of Thrones – Ramin Djawadi 7. Planting the Fields – Robin Hood – Marc Streitenfeld 8. More Prays – The Tudors – Trevor Morris 9. Jarl Borg Attacks Kattegat – Vikings – Trevor Morris 10. Henry in Solitude – The Tudors – Trevor Morris 11. Flight to the Ford – Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring – Howard Shore 12. Traitors – Spooks – Paul Leonard-Morgan 13. Oil Rig – Man of Steel – Hans Zimmer 14. Votan Romance – Defiance – Bear McCreary 15. Almost Midnight – Gears of War 4 – Ramin Djawadi 16. Await the King’s Justice – Game of Thrones – Ramin Djawadi 17. Masha’s Song – Anna Karenina – Dario Marianelli 18. Mirena – Dracula Untold – Ramin Djawadi 19. Sulphur Bath Assassination – The Borgias – Trevor Morris 20. You Shouldn’t Walk In Shadows – The Huntsman: Winter’s War – James Newton Howard 21. A Fight In Court – The Tudors – Trevor Morris 22. The Shape of Things To Come – The Tudors – Trevor Morris PART TWO 1. Ignition – Man of Steel – Hans Zimmer 2. Jane’s Story – Jane Got a Gun – Lisa Gerrard & Marcello De Francisci 3. Katniss – The Hunger Games – James Newton Howard 4. Henry Talks To His Fool – The Tudors – Trevor Morris 5. Speechless – Beyond the Gates – Dario Marianelli 6. The Lullaby – Da Vinci’s Demons – Bear McCreary 7. Monkey Drone Projector – Emerald City – Trevor Morris 8. -

Note Di Produzione “Io E Mia Sorella? Noi Abbiamo Un Passato!” -- Hansel

Note di produzione “Io e mia sorella? Noi abbiamo un passato!” -- Hansel Azione frenetica, divertimento, brividi sinistri, modernità e scaltrezza trasformano una favola leggendaria nella vivace avventura action-horror Hansel & Gretel: Cacciatori di streghe. La storia comincia 15 anni dopo che i fratelli Hansel (Jeremy Renner) e Gretel (Gemma Arterton) sono riusciti a escogitare un piano per fuggire da una strega cattura-bambini che ha cambiato le loro vite per sempre…. lasciando loro il gusto del sangue. Ora sono dei cacciatori di taglie cresciuti, fieri, formidabilmente capaci e dediti al 100% a cacciare e fare fuori le streghe di ogni scura foresta – decisi a punirle. Ma quando si avvicina la famigerata ‘Luna di Sangue’ e i bambini innocenti di una cittadina nel bosco si trovano a vivere un incubo, Hansel & Gretel incontrano un male che va oltre ogni strega che loro abbiano mai inseguito – un male che potrebbe conoscere il segreto del loro spaventoso passato. Paramount Pictures e Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures presentano una produzione Gary Sanchez con Jeremy Renner, Gemma Arterton, Famke Janssen e Peter Stormare, Hansel & Gretel: Cacciatori di streghe. Il film è scritto e diretto da Tommy Wirkola. I produttori sono Will Ferrell, Adam McKay, Kevin Messick e Beau Flynn e i produttori esecutivi sono Denis L. Stewart, Chris Henchy e Tripp Vinson. Da vita all’ipnotizzante mondo visivo di Hansel & Gretel una squadra che comprende: il direttore della fotografia Michael Bonvillain (Cloverfield), lo scenografo Stephen Scott (Hellboy, Hellboy 2), il montatore Jim Page (Disturbia), la costumista Marlene Stewart (Real Steel, Tropic Thunder); la musica è di Atli Örvasson, l’executive music producer è Hans Zimmer e il supervisore agli effetti speciali Jon Farhat (Codice Genesi, Wanted – Scegli il tuo destino). -

Bake-Off” TV Contenders

****FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE**** Press Contact: Costa Communications Ray Costa | Kelsey Kempe (323) 650-3588 [email protected] | [email protected] The Hollywood Music in Media Awards Announces first round “bake-off” TV contenders Ceremony to be held Thursday, November 16, 2017 at The Avalon in Hollywood. (Hollywood, CA) – June 21, 2017 – The Hollywood Music in Media Awards (HMMA) announced today a “bake-off” list in the TV categories of song and score. The HMMA nominations have historically been representative of the nominees of key awards shows that are announced months later. Music nominees are chosen in specific genres for films including dramatic feature, Sci-Fi Fantasy, documentary and animation. Two years ago, the Golden Globe nominees for score matched the HMMA’s selections. This past year, and months before the Oscar nominations, song and score nominees virtually matched Oscars including HMMA song winner “City of Stars” from LA LA LAND by Justin Hurwitz, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul. For the HMMA bakeoff Oscar winners Pasek & Paul are competing for TV song from CW’s “The Flash” against contenders including documentary songwriters’ Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross for NatGeo’s “Before The Flood” as well as Alan Zachary and Michael Weiner for ABC’s “Once Upon A Time.” Score contenders include Discovery Channel’s “Sonic Sea,” NatGeo’s “Genius,” “The Crown,” “Feud” and more. Many legendary film composers are contenders for TV projects including Hans Zimmer, Gustavo Santaolala, Trent Reznor, Atticus Ross, Thomas Newman This marks the first year that the HMMAs have recognized TV contenders prior to the Emmys. According to HMMA Executive Producer Brent Harvey, “the judging panel is made up of journalists, composers, songwriters, music supervisors, along with music executives from film, TV and videogames; they continue to be a barometer for contenders in other award shows. -

AT the M 0 VIES with Music Supervisors, Drove Home the Point That Music Needs to Be Cleared Easily, Preferably Around the World

Billboard / /O1 /í7111)O(/ FILM &TV CONFERENCEMUSIC "Glee" star serenades composer (far left) by playfully altering lyrics from his songs from 'Beauty and the Beast" and "The Lion King," amusing Billboard editorial director . A fan of Menken's work since he was a youngster, Criss spoke of his days at the University of Michigan where he'd perform Menken's material. Once Criss finished his parodies, singer/actress joined him to sing "A Whole New World" from "Aladdin." Below, Menken, Salonga and Criss share a moment after the panel. ness to independent music and undiscovered artists. They, along AT THE M 0 VIES with music supervisors, drove home the point that music needs to be cleared easily, preferably around the world. Hiccups in the process, Disney Channel's Steve Vincent said, mean "the song From award- winning composers to is dead to me." Two panels in particular drew rave reviews from attendees. Darren Criss to esteemed music sup err»sors On day one, musicians known for their pop, rock, folk and gos- pel work shared their experiences when crossing over into film. the conference was a really big show Linkin Park's Mike Shinoda, who's finishing his first score for the Sony film "The Raid," said, "I was kind of afraid to stretch myself too thin, but we made it work and it has gone more quickly The creative process in film, TV and, especially, ani- Disney animation songstress Lea Salonga surprised Maestro that I ever thought, which bodes well for the next project, what- mation was thoroughly examined at the two -day Award winner Alan Menken with a performance that included ever that might be." Billboard /Hollywood Reporter Film & TV Music "A Whole New World" and humorous reworking of Menken's Twentieth Century Fox president of music Robert Kraft, who Conference, while prominent music supervisors got tunes from his Academy Award -winning films like "The Lion moderated the panel that included Take 6 co- founder Mervyn into the nitty gritty about budgets.