Coosa River South River Floridan Aquifer Georgia's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stream-Temperature Characteristics in Georgia

STREAM-TEMPERATURE CHARACTERISTICS IN GEORGIA By T.R. Dyar and S.J. Alhadeff ______________________________________________________________________________ U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 96-4203 Prepared in cooperation with GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION Atlanta, Georgia 1997 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 3039 Amwiler Road, Suite 130 Denver Federal Center Peachtree Business Center Box 25286 Atlanta, GA 30360-2824 Denver, CO 80225-0286 CONTENTS Page Abstract . 1 Introduction . 1 Purpose and scope . 2 Previous investigations. 2 Station-identification system . 3 Stream-temperature data . 3 Long-term stream-temperature characteristics. 6 Natural stream-temperature characteristics . 7 Regression analysis . 7 Harmonic mean coefficient . 7 Amplitude coefficient. 10 Phase coefficient . 13 Statewide harmonic equation . 13 Examples of estimating natural stream-temperature characteristics . 15 Panther Creek . 15 West Armuchee Creek . 15 Alcovy River . 18 Altamaha River . 18 Summary of stream-temperature characteristics by river basin . 19 Savannah River basin . 19 Ogeechee River basin. 25 Altamaha River basin. 25 Satilla-St Marys River basins. 26 Suwannee-Ochlockonee River basins . 27 Chattahoochee River basin. 27 Flint River basin. 28 Coosa River basin. 29 Tennessee River basin . 31 Selected references. 31 Tabular data . 33 Graphs showing harmonic stream-temperature curves of observed data and statewide harmonic equation for selected stations, figures 14-211 . 51 iii ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1. Map showing locations of 198 periodic and 22 daily stream-temperature stations, major river basins, and physiographic provinces in Georgia. -

Chemical Character of Surface Waters of Georgia

SliEU' :\0..... / ........ RO O ~ l NO. ···- ··-<~ ......... U )'On no l~er need this publication write to the Geological Sur»ey in Washlndon for ali official maillne label to use In returning it UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CHEMICAL CHARACTER OF SURFACE WATERS OF GEORGIA Prepared In cooperation wilh the DIVISION OF MINES, MINING, AND GEOLOGY OF 'l'HE GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 889- E ' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director Water-Supply Paper 889-E CHEMICAL CHARACTER OF SURFACE WATERS OF GEORGIA BY WILLIAM L. LAMAR Prepared in cooperation with the DIVISION OF MINES, MINING, AND GEOLOGY OF THE GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Contributions to the Hydrology of the United States, 19~1-!3 (Pages 317- 380) UN ITED STATES GOVEHNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1944 For sct le Ly Ll w S upcrinkntlent of Doc uments, U. S. Gover nme nt Printing Office, " ' asbingtou 25, D . C. Price 15 ce nl~ CONTENTS Page- Abstract ___________________________________________ -----_--------- 31 T Introduction __________________ c ________________________________ -- _ 317 Physiography_____________________________________________________ 318 Climate__________________________________________________________ 820 Collection and examination of samples_______________________________ 323 Stream flow __________________________ --------- ___________ c ________ . 324 Rainfall and discharge during sampling years_____________________ -

11-1 335-6-11-.02 Use Classifications. (1) the ALABAMA RIVER BASIN Waterbody from to Classification ALABAMA RIVER MOBILE RIVER C

335-6-11-.02 Use Classifications. (1) THE ALABAMA RIVER BASIN Waterbody From To Classification ALABAMA RIVER MOBILE RIVER Claiborne Lock and F&W Dam ALABAMA RIVER Claiborne Lock and Alabama and Gulf S/F&W (Claiborne Lake) Dam Coast Railway ALABAMA RIVER Alabama and Gulf River Mile 131 F&W (Claiborne Lake) Coast Railway ALABAMA RIVER River Mile 131 Millers Ferry Lock PWS (Claiborne Lake) and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Millers Ferry Sixmile Creek S/F&W (Dannelly Lake) Lock and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Sixmile Creek Robert F Henry Lock F&W (Dannelly Lake) and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Robert F Henry Lock Pintlala Creek S/F&W (Woodruff Lake) and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Pintlala Creek Its source F&W (Woodruff Lake) Little River ALABAMA RIVER Its source S/F&W Chitterling Creek Within Little River State Forest S/F&W (Little River Lake) Randons Creek Lovetts Creek Its source F&W Bear Creek Randons Creek Its source F&W Limestone Creek ALABAMA RIVER Its source F&W Double Bridges Limestone Creek Its source F&W Creek Hudson Branch Limestone Creek Its source F&W Big Flat Creek ALABAMA RIVER Its source S/F&W 11-1 Waterbody From To Classification Pursley Creek Claiborne Lake Its source F&W Beaver Creek ALABAMA RIVER Extent of reservoir F&W (Claiborne Lake) Beaver Creek Claiborne Lake Its source F&W Cub Creek Beaver Creek Its source F&W Turkey Creek Beaver Creek Its source F&W Rockwest Creek Claiborne Lake Its source F&W Pine Barren Creek Dannelly Lake Its source S/F&W Chilatchee Creek Dannelly Lake Its source S/F&W Bogue Chitto Creek Dannelly Lake Its source F&W Sand Creek Bogue -

Guidelines for Eating Fish from Georgia Waters 2017

Guidelines For Eating Fish From Georgia Waters 2017 Georgia Department of Natural Resources 2 Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, S.E., Suite 1252 Atlanta, Georgia 30334-9000 i ii For more information on fish consumption in Georgia, contact the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Environmental Protection Division Watershed Protection Branch 2 Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, S.E., Suite 1152 Atlanta, GA 30334-9000 (404) 463-1511 Wildlife Resources Division 2070 U.S. Hwy. 278, S.E. Social Circle, GA 30025 (770) 918-6406 Coastal Resources Division One Conservation Way Brunswick, Ga. 31520 (912) 264-7218 Check the DNR Web Site at: http://www.gadnr.org For this booklet: Go to Environmental Protection Division at www.gaepd.org, choose publications, then fish consumption guidelines. For the current Georgia 2015 Freshwater Sport Fishing Regulations, Click on Wild- life Resources Division. Click on Fishing. Choose Fishing Regulations. Or, go to http://www.gofishgeorgia.com For more information on Coastal Fisheries and 2015 Regulations, Click on Coastal Resources Division, or go to http://CoastalGaDNR.org For information on Household Hazardous Waste (HHW) source reduction, reuse options, proper disposal or recycling, go to Georgia Department of Community Affairs at http://www.dca.state.ga.us. Call the DNR Toll Free Tip Line at 1-800-241-4113 to report fish kills, spills, sewer over- flows, dumping or poaching (24 hours a day, seven days a week). Also, report Poaching, via e-mail using [email protected] Check USEPA and USFDA for Federal Guidance on Fish Consumption USEPA: http://www.epa.gov/ost/fishadvice USFDA: http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/seafood.1html Image Credits:Covers: Duane Raver Art Collection, courtesy of the U.S. -

Closure Plan

CLOSURE PLAN PLANT SCHERER - ASH POND 1 (AP-1) MONROE COUNTY, GEORGIA FOR November 2018 AECOM, 1600 Perimeter Park Drive, Suite 400 Morrisville, NC 27560, (919) 461-1230, (919) 461-1415 PAGE INTENTIALLY LEFT BLANK November 2018 Plant Scherer – Ash Pond 1 (AP-1) Closure Closure Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBEVIATIONS .................................................................................................... 1-3 1 General ...................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Site Background .................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Notification .............................................................................................................................................. 1-2 1.3 Boundary Survey and Legal Description ....................................................................................... 1-2 2 Closure Plan ............................................................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Closure Configuration and Components ...................................................................................... 2-2 2.2 Conceptual Closure Sequence ........................................................................................................ 2-4 2.3 Directional Informational Signs ....................................................................................................... -

Ethnographic Overview and Assessment of Ocmulgee National Monument

FINAL REPORT September 2014 Ethnographic Overview and Assessment of Ocmulgee National Monument for the National Park Service Task Agreement No. P11AT51123 Deborah Andrews Peter Collings Department of Anthropology University of Florida Dayna Bowker Lee 1 I. Introduction, by Deborah Andrews 6 II. Background: The History of Ocmulgee National Monument 8 A. The Geography of Place 8 B. Preservation and Recognition of Ocmulgee National Monument 10 1. National Monument Designation 10 2. Depression Era Excavations 13 C. Research on and about Ocmulgee National Monument 18 III. Ethnohistory and Archaeology of Ocmulgee National Monument 23 A. The Occupants and Features of the Site 23 1. The Uchee Trading Path 24 2. PaleoIndian, Archaic and Woodland Eras 27 3. The Mississippian Mound Builders 37 4. The Lamar Focus and Migration 47 5. Proto-historic Creek and Spanish Contact 56 6. Carolina Trading Post and English Contact 59 7. The Yamassee War 64 8. Georgia Colony, Treaties and Removal 66 B. Historic Connections, Features and Uses of the Site 77 1. The City of Macon 77 2. Past Historic Uses of the Site 77 a. The Dunlap Plantation 78 b. Civil War Fortification 80 c. Railroads 81 2 d. Industry and Clay Mining 83 e. Interstate 16 84 f. Recreation and Education 85 C. Population 87 IV. Contemporary Views on the Ocmulgee National Monument Site, by Dayna Bowker Lee 93 A. Consultation 93 B. Etvlwu: The Tribal Town 94 C. The Upper and Lower Creek 98 D. Moving the Fires: The Etvlwv in Indian Territory, Oklahoma 99 E. Okmulgee in the West 104 F. -

September 28, 2020 VIA ELECTRONIC FILING Ms

Troutman Pepper Hamilton Sanders LLP 301 S. College Street, Suite 3400 Charlotte, NC 28202 troutman.com Kiran H. Mehta [email protected] September 28, 2020 VIA ELECTRONIC FILING Ms. Kimberley A. Campbell, Chief Clerk North Carolina Utilities Commission 4325 Mail Service Center Raleigh, North Carolina 27699-4300 RE: Duke Energy Progress, LLC’s Motion for Leave to Designate Late-Filed Potential Cross Exhibits Docket No. E-2, Sub 1219 Dear Ms. Campbell: On behalf of Duke Energy Progress, LLC (the “Company”), please find enclosed for electronic filing a motion for leave to designate late-filed potential cross-examination exhibits. Please do not hesitate to contact me should have you have any questions. Thank you for your assistance in this matter. Sincerely, /s/ Kiran H. Mehta Kiran H. Mehta Enclosures cc: Parties of Record BEFORE THE NORTH CAROLINA UTILITIES COMMISSION STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA UTILITIES COMMISSION RALEIGH DOCKET NO. E-2, SUB 1219 DOCKET NO. E-2, SUB 1219 ) ) DUKE ENERGY PROGRESS, LLC’S In the Matter of ) MOTION FOR LEAVE TO ) DESIGNATE LATE-FILED Application by Duke Energy Progress, ) POTENTIAL CROSS EXHIBITS LLC for Adjustment of Rates and ) Charges Applicable to Electric Utility ) Service in North Carolina ) ) NOW COMES Duke Energy Progress, LLC (“DE Progress” or the “Company”), by and through its legal counsel and pursuant to Rules R1-7 and R1-24 of the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina Utilities Commission (“Commission”), and hereby requests leave to designate as DEP Exhibit 75 Sierra Club witness Rachel Wilson’s direct testimony and exhibit RW-4 (Quarles Report) from Georgia Power Company’s 2019 Rate Case docket. -

(2019) EPA's Final

Attachment to Part B Comments of Earthjustice et al., EPA-HQ-OLEM-2019-0173 Assessment Monitoring Outcomes (2019) EPA’s Final Coal Ash Rule, 40 C.F.R. § 257.94(e)(3), requires the owners or operators of existing Coal Combustion Residuals (CCR) units to prepare a notification stating that an assessment monitoring program has been established if it is determined that a statistically significant increase over background levels for one or more of the constituents listed in appendix III of the CCR Rule has occurred, without an alleged alternate source demonstration. This table identifies the CCR surface impoundments known to be in assessment monitoring and required to identify any constituent(s) in appendix IV detected at statistically significant levels (SSL) above groundwater protection standards and post notice of the assessment monitoring outcome per 40 C.F.R. § 257.95. The table includes the surface impoundments that were required to post notice of appendix IV exceedance(s), as applicable, or elected to do so as of the time of this assessment monitoring outcomes review (summer 2019). To the best of our knowledge, neither EPA nor any other entity has attempted to assemble this information and make it public. Note that this document is not confirming that the industry notifications or assessments were compliant with the CCR Rule or that additional units may not belong on this list. Assessment Monitoring Outcome # of Surface Impoundments Appendix IV Exceedance(s) 214 Appendix IV Exceedance(s), alleged Alternate Source Demonstration 16 No Appendix IV Exceedance Reported 64 Total 294 Name of Plant Appendix IV Operator CCR Unit or Site Exceedance(s) Healy Power Plant GVEA AK Unit 1 Ash Pond Yes Healy Power Plant GVEA AK Unit 1 Emergency Overflow Pond Yes Healy Power Plant GVEA AK Unit 1 Recirculating Pond Yes Charles R. -

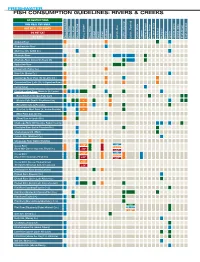

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk. -

Savannah River Basin Management Plan 2001

Savannah River Basin Management Plan 2001 Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Georgia River Basin Management Planning Vision, Mission, and Goals What is the VISION for the Georgia RBMP Approach? Clean water to drink, clean water for aquatic life, and clean water for recreation, in adequate amounts to support all these uses in all river basins in the state of Georgia. What is the RBMP MISSION? To develop and implement a river basin planning program to protect, enhance, and restore the waters of the State of Georgia, that will provide for effective monitoring, allocation, use, regulation, and management of water resources. [Established January 1994 by a joint basin advisory committee workgroup.] What are the GOALS to Guide RBMP? 1) To meet or exceed local, state, and federal laws, rules, and regulations. And be consistent with other applicable plans. 2) To identify existing and future water quality issues, emphasizing nonpoint sources of pollution. 3) To propose water quality improvement practices encouraging local involvement to reduce pollution, and monitor and protect water quality. 4) To involve all interested citizens and appropriate organizations in plan development and implementation. 5) To coordinate with other river plans and regional planning. 6) To facilitate local, state, and federal activities to monitor and protect water quality. 7) To identify existing and potential water availability problems and to coordinate development of alternatives. 8) To provide for education of the general public on matters involving the environment and ecological concerns specific to each river basin. 9) To provide for improving aquatic habitat and exploring the feasibility of re-establishing native species of fish. -

Chattahoochee River: 4 Unhealthy River Flows Threaten the Chattahoochee

2011’s worst offenses against Georgia’s Water # Chattahoochee River: 4 Unhealthy River Flows Threaten the Chattahoochee In the late summer, when residents turn up their air conditioners and the Coosa River is at its lowest, Georgia Power Co.’s Plant Hammond burns coal to keep residents cool—and withdraws up to 590 million gallons a day from the river. During times of drought when river flows dip as low as 460 million gallons a day, the river literally flows upstream at the plant’s intake pipes. Used to cool the coal-plant’s operating system, the water is discharged back to the river at higher temperatures that degrade water quality. The River: The Coosa River in Georgia feeds Weiss Lake in Alabama, a 30,200-acre Alabama Power reservoir that is the economic calling-card for Centre, Alabama and Cherokee County. Tourism associated with the lake is the county’s primary industry, with an economic impact of $250 million annually. More than 450,000 people visit the lake each year and some 4,132 lakerelated #4 jobs generate more than $36 million in wages. The Upper Coosa River Basin Chattahoochee River is considered North America’s most biologically-diverse river basin with 30 endemic aquatic species, and the Coosa River in particular is unique because it is one of only a handful of locations in the country where land-locked striped bass still spawn. The Dirt: Power generating facilities are the biggest users of water in Georgia, and Georgia Power’s Plant Hammond is one of a handful of coal-fired power plants in the state that still rely on out-dated “once-through cooling systems.” These systems require massive amounts of water from our rivers to cool the plant’s operating system. -

Coosa River Lake Lanier Georgia's Rural

GEORGIA’S HEADWATER STREAMS COOSA RIVER LAKE LANIER GEORGIA’S RURAL COMMUNITIES GEORGIA’S PUBLIC HEALTH CHATTAHOOCHEE RIVER OCMULGEE RIVER ALTAMAHA RIVER TERRY CREEK ST. SIMONS OKEFENOKEE SOUND SWAMP ST. MARYS RIVER 2019’s Worst Offenses Against GEORGIA’S WATER GEORGIA WATER COALITION’S DIRTY DOZEN A Call to Action The Georgia Water Coalition’s Dirty Dozen list highlights the politics, policies and issues that threaten the health of Georgia’s water and the well-being of 10 million Georgians. The purpose of the report is not to identify the state’s “most polluted places.” Instead the report is a call to action for Georgia’s leaders and its citizens to solve ongoing pollution problems, eliminate potential threats to Georgia’s water and correct state and federal policies and actions that lead to polluted water. Unfortunately, this year’s report includes seven issues that are making return visits to this inauspicious list. Topping that category is pollution of the Altamaha River from the Rayonier Advanced Materials (RAM) chemical pulp mill in Jesup. The facility is making a record seventh appearance in the Dirty Dozen report because pollution from the mill continues. Next year, Georgia’s Environmental Protection Division (EPD) will issue a new pollution control permit for the facility, but if EPD’s actions in recent years are any indication, it seems unlikely that this new permit will fix this ongoing pollution problem. The state agency has repeatedly defended the existing and weak The Georgia Water Coalition’s Dirty Dozen report is a pollution control permit and last year took the extraordinary step of call to action for Georgia’s leaders and citizens to solve changing state laws to make it easier for RAM to continue polluting ongoing pollution problems, eliminate potential threats Georgia’s largest river.