DORMAN-THESIS-2018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mini Hd Mały Hd Duży Hd Mega Hd Mega + Hd

MINI HD MAŁY HD DUŻY HD MEGA HD MEGA + HD TVP1 HD TVP1 HD TVP1 HD TVP1 HD TVP1 HD TVP2 HD TVP2 HD TVP2 HD TVP2 HD TVP2 HD TVN HD TVN HD TVN HD TVN HD TVN HD Polsat HD Polsat HD Polsat HD Polsat HD Polsat HD TV4 TV4 TV4 TV4 TV4 TV6 TV6 TV6 TV6 TV6 TVN7 HD TVN7 HD TVN7 HD TVN7 HD TVN7 HD TTV TTV TTV TTV TTV Polsat 2 Polsat 2 BBC HD BBC HD BBC HD TVP Polonia TVP Polonia TVP HD TVP HD TVP HD TV Puls TV Puls Polsat 2 Polsat 2 Polsat 2 Puls 2 Puls 2 TVP Polonia TVP Polonia TVP Polonia Tele 5 Tele 5 TV Puls TV Puls TV Puls Polonia 1 Polonia 1 Puls 2 Puls 2 Puls 2 Mango 24 Mango 24 Tele 5 Tele 5 Tele 5 ATM Rozrywka TV ATM Rozrywka Polonia 1 Polonia 1 Polonia 1 Religia TV Edusat HD Mango 24 Mango 24 Mango 24 TV Trwam TVR HD ATM Rozrywka ATM Rozrywka ATM Rozrywka Kościół HD na żywo TVS HD Edusat HD Edusat HD Edusat HD Polsat Sport News Religia TV TVR HD TVR HD TVR HD TVP Info Szczecin TV Trwam TVS HD TVS HD TVS HD TVP Info Gorzów Kościół HD na żywo Religia TV Religia TV Religia TV TVP Info Polsat Sport News TV Trwam TV Trwam TV Trwam TVP Łódź TVN 24 HD Kościół HD na żywo Kościół HD na żywo Kościół HD na żywo TVP Wrocław Polsat News Polsat Sport News Polsat Sport News Polsat Sport News TVP Warszawa Polsat Biznes TVN 24 HD TVN 24 HD TVN 24 HD TVP Rzeszów TVN Biznes i Świat Polsat News Polsat News Polsat News TVP Olsztyn TVP Info Szczecin Polsat Biznes Polsat Biznes Polsat Biznes TVP Katowice TVP Info Gorzów TVN Biznes i Świat TVN Biznes i Świat TVN Biznes i Świat TVP Gdańsk TVP Info TVP Info Szczecin TVP Info Szczecin TVP Info Szczecin Stopklatka -

Lista Kanałów

SUPER HD 158 kanały w tym 76 HD KOMFORT HD 143 kanały w tym 65 HD START EXTRA HD 111 kanałów w tym 43 HD 1 TVP1 HD HD 110 France 24 FR HD HD 600 TVP Rozrywka 900 TVP1 2 TVP2 HD HD 111 France 24 EN HD HD 601 ATM Rozrywka 901 TVP2 3 TVP3 Wrocław 113 TwojaTV HD HD 602 RedCarpet TV HD HD 902 TVN 4 TV4 HD HD 200 TVN Fabuła HD HD 607 TVR HD HD 903 TVN7 5 TV6 HD HD 204 Stopklatka.tv HD HD 609 Super Polsat HD HD 904 Puls 6 TVN HD HD 300 TVP Kultura 610 NowaTV HD HD 905 Puls 2 7 TVN7 HD HD 301 TVP Historia 611 ToTV 906 TTV 10 Polsat HD HD 303 FokusTV HD HD 612 WP 907 Tele5 11 Polsat 2 HD HD 310 Polsat Doku HD HD 613 SBN Network 908 Zoom TV 12 Puls HD HD 311 Russia Today DOC HD HD 615 Polsat Games HD HD 909 MetroTV 13 Puls 2 HD HD 400 TVP Sport HD HD 616 Polsat Rodzina HD HD 910 FokusTV 14 TTV HD HD 403 Polsat Sport News HD HD 620 GameToon HD HD 911 NowaTV 15 TVP Polonia 404 Polsat Sport Fight HD HD 800 TVP3 Warszawa 912 TVS 16 Polonia 1 500 4FUN TV 801 TVP3 Gdańsk 913 TVP INFO 17 TVP ABC 501 4FUN GOLDS HITS 802 TVP3 Szczecin 914 Russia Today 18 Tele5 HD HD 502 4FUN DANCE 803 TVP3 Poznań 915 Russia Today DOC 22 Zoom TV HD HD 504 VOX Music TV 804 TVP3 Białystok 916 TVR 23 WP HD HD 505 Polsat Music HD HD 805 TVP3 Olsztyn 917 RedCarpet TV SD 24 MetroTV HD HD 506 Eska TV HD HD 806 TVP3 Bydgoszcz 922 Stopklatka.tv 25 NTL Radomsko 507 Eska TV Extra HD HD 807 TVP3 Gorzów 923 Eska TV 26 Nobox TV 508 Eska Rock TV 808 TVP3 Lublin 924 Eska TV Extra 102 TVP INFO HD HD 509 PowerTV HD HD 809 TVP3 Rzeszów 925 PowerTV 104 Polsat News 2 510 Nuta.TV HD HD 810 TVP3 -

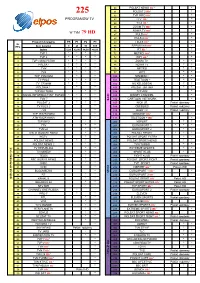

Programów Tv

60 POLSAT NEWS HD 1 * 225 61 POLSAT 2 HD 1 * 62 TVP INFO HD 1 * PROGRAMÓW TV 63 TTV HD 1 * 64 TV 4 HD 1 * 65 ZOOM TV HD 1 * 66 NOWA TV HD 1 * W TYM 79 HD 1 67 PULS HD * 68 PULS 2 HD 1 * Program telewizyjny PR P1 P2 P3 69 TELE5 HD 1 * Nr 1 EPG Ilość kanałów 9 21 91 169 70 REPUBLIKA HD * Opłata 5,00 12,00 34,00 46,00 71 RT HD 1 * 1 TVP 1 * * * * 72 METRO HD 1 * 2 TVP 2 * * * * 73 WP1 HD 1 * 3 TVP 3 BIAŁYSTOK * * * * 74 ZOOM TV * * 4 POLSAT * * * * 75 NOWA TV * * 5 TVN * * * * 76 METRO * * 6 TV4 * * * * 77 WP1 * * 7 TVP POLONIA * * 100 MINIMINI + * * 8 TV PULS * * * * 101 TELETOON + * * 9 TV TRWAM * * * * 102 NICKELODEON * * 10 POLONIA 1 * * 103 POLSAT JIM JAM * * 11 TVP KULTURA * * 104 TVP ABC * I 12 KANAŁ INFORMACYJNY ELPOS * * * * K 105 DISNEY CHANNEL * J 13 TVN 7 * * * A 106 CARTOON NETWORK * B 14 POLSAT 2 * * * 107 NICK JR Pakiet domowy 15 TV PULS 2 * 108 CBEEBIES Pakiet rodzinny 16 TV6 * * 109 BABY TV Pakiet rodzinny 17 TVP ROZRYWKA * 110 MINIMINI+ HD 1 * 18 ATM ROZRYWKA * 111 TELETOON + HD 1 * 19 TVP INFO * * 200 NSPORT * * 20 TTV * * 201 EUROSPORT 1 * * * 21 TVN 24 * * 202 EUROSPORT 2 * * 22 TVN 24 BIZNES I ŚWIAT * * 203 POLSAT SPORT * * * 23 HGTV * * 204 POLSAT SPORT EXTRA * * 24 POLSAT NEWS * * * 205 POLSAT SPORT NEWS * * 25 POLSAT NEWS 2 * * 206 TVN TURBO * * E 26 TV REPUBLIKA * * 207 EXTREME SPORTS * * N J 27 TV NAREW * * 208 SPORT KLUB * * Y C 28 TELE5 * * 209 FIGHT KLUB Pakiet sportowy A M 29 BBC WORLD NEWS * * 210 POLSAT SPORT FIGHT Pakiet sportowy R O F 30 CNBC * * 211 TVP SPORT Pakiet sportowy N T I 1 I 31 * R 212 HD CNN -

UNIVERSITY of BELGRADE FACULTY of POLITICAL SCIENCE Regional Master's Program in Peace Studies MASTER's THESIS Revisiting T

UNIVERSITY OF BELGRADE FACULTY OF POLITICAL SCIENCE Regional Master’s Program in Peace Studies MASTER’S THESIS Revisiting the Orange Revolution and Euromaidan: Pro-Democracy Civil Disobedience in Ukraine Academic supervisor: Student: Associate Professor Marko Simendić Olga Vasilevich 9/18 Belgrade, 2020 1 Content Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………3 1. Theoretical section……………………………………………………………………………..9 1.1 Civil disobedience…………………………………………………………………………9 1.2 Civil society……………………………………………………………………………... 19 1.3 Nonviolence……………………………………………………………………………... 24 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………… 31 2. Analytical section……………………………………………………………………………..33 2.1 The framework for disobedience………………………………………………….…….. 33 2.2 Orange Revolution………………………………………………………………………. 40 2.3 Euromaidan……………………………………………………………………………… 47 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………… 59 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………… 62 References……………………………………………………………………………………….67 2 INTRODUCTION The Orange Revolution and the Revolution of Dignity have precipitated the ongoing Ukraine crisis. According to the United Nations Rights Office, the latter has claimed the lives of 13,000 people, including those of unarmed civilian population, and entailed 30,000 wounded (Miller 2019). The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees adds to that 1.5 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), 100,000 refugees and asylum-seekers (UNHCR 2014). The armed conflict is of continued relevance to Russia, Europe, as well as the United States. During the first 10 months, -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

Lista Kanałów Finetv

SUPER HD 182 kanały w tym 85 HD i 1 w 4K KOMFORT HD 156 kanały w tym 70 HD i 1 w 4K START EXTRA HD 117 kanałów w tym 44 HD i 1 w 4K 1 TVP1 HD HD 300 TVP Kultura HD HD 616 Polsat Rodzina HD HD 916 TVS 2 TVP2 HD HD 301 TVP Historia 620 GameToon HD HD 917 TVP INFO 3 TVP3 Wrocław 303 FokusTV HD HD 800 TVP3 Warszawa 918 Russia Today 4 TV4 HD HD 310 Polsat Doku HD HD 801 TVP3 Gdańsk 919 Russia Today DOC 5 TV6 HD HD 311 Russia Today DOC HD HD 802 TVP3 Szczecin 920 TVR 6 TVN HD HD 317 Jazz HD HD 803 TVP3 Poznań 921 RedCarpet TV SD 7 TVN7 HD HD 400 TVP Sport HD HD 804 TVP3 Białystok 929 Stopklatka.tv 10 Polsat HD HD 403 Polsat Sport News HD HD 805 TVP3 Olsztyn 930 Eska TV 11 Polsat 2 HD HD 404 Polsat Sport Fight HD HD 806 TVP3 Bydgoszcz 931 Eska TV Extra 12 Puls HD HD 500 4FUN TV 807 TVP3 Gorzów 932 PowerTV 13 Puls 2 HD HD 501 4FUN GOLDS HITS 808 TVP3 Lublin 933 Nuta.TV 14 TTV HD HD 502 4FUN DANCE 809 TVP3 Rzeszów 934 StarsTV 15 TVP Polonia 504 VOX Music TV 810 TVP3 Kraków 935 TVP Kultura 16 Polonia 1 505 Polsat Music HD HD 811 TVP3 Opole 936 TVP Sport 17 TVP ABC 506 Eska TV HD HD 812 TVP3 Kielce 937 TBN Poland 18 Tele5 HD HD 507 Eska TV Extra HD HD 813 TVP3 Łódź 938 Mango 24 22 Zoom TV HD HD 508 Eska Rock TV 814 TVP3 Katowice 939 TV Trwam 23 WP HD HD 509 PowerTV HD HD 900 TVP1 999 Radio Przy Kominku HD 24 MetroTV HD HD 510 Nuta.TV HD HD 901 TVP2 25 NTL Radomsko 511 StarsTV HD HD 902 TVN 26 Nobox TV 512 PoloTV 903 TVN7 102 TVP INFO HD HD 513 MusicBox UA 904 Puls 104 Polsat News 2 514 Kino Polska Muzyka 905 Puls 2 105 wPolsce.PL 600 TVP Rozrywka -

Mass Media in Belarus E-Newsletter

MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS ThE Belarusian E-NEWSLETTER ASSociatioN of JoURNALISTS www.baj.By January – March 2014 svaboda.org MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS E-NEWSLETTER January – March 2014 The economic, legal, political, and technological resources of non-state and state media differ significantly. Talking about social and political media, one non-state media outlet falls on nine state media outlets in Belarus. Despite the incompa- rable activity scale of state and non-state media as well as their unequal working conditions, the level of confidence in these completely different media is quite comparable. It ap- pears that the state media in our country exert a larger influ- ence on the society due to their quantity and unequal favora- ble conditions. It is not an indicator of their quality though. Aleh Manayeu, the founder of Independent Institute of Social, Economic, and Political Studies - “Your Country’s Tomorrow” 02 MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS E-NEWSLETTER January – March 2014 CONTENTS: Main Events in Mass Media Field in January-March 2014 . 4 Rating Lists, Indexes, Statistics . 12 03 MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS E-NEWSLETTER MAIN EVENTS January – March 2014 IN MASS MEDIA FIELD IN JANUARY-MARCH 2014 The major trends of the second half-year of 2013 remained in the Belarusian media field in the first quarter of 2014. Among other, they included: • the obstruction of professional journalistic activity by means of detaining journalists, issuing official warnings etc .; • the use of anti-extremism legislation to restrict the freedom of expression; • the restriction of Internet freedom . on the eve of Local Elections on March 23, 2014, there became more frequent the attempts to mis- inform the population and mass media by means of disseminating fake messages on behalf of media per- sonalities or by means of establishing fake accounts in the social media. -

Ukraine Local Elections, 25 October 2015

ELECTION OBSERVATION DELEGATION TO THE LOCAL ELECTIONS IN UKRAINE (25 October 2015) Report by Andrej PLENKOVIĆ, ChaIr of the Delegation Annexes: A - List of Participants B - EP Delegation press statement C - IEOM Preliminary Findings and Conclusions on 1st round and on 2nd round 1 IntroductIon On 10 September 2015, the Conference of Presidents authorised the sending of an Election Observation Delegation, composed of 7 members, to observe the local elections in Ukraine scheduled for 25 October 2015. The Election Observation Delegation was composed of Andrej Plenkovič (EPP, Croatia), Anna Maria Corazza Bildt (EPP, Sweden), Tonino Picula (S&D, Croatia), Clare Moody (S&D, United Kingdom), Jussi Halla-aho (ECR, Finland), Kaja Kallas (ALDE, Estonia) and Miloslav Ransdorf (GUE, Czech Republic). It conducted its activities in Ukraine between 23 and 26 October, and was integrated in the International Election Observation Mission (IEOM) organised by ODIHR, together with the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities. On election-day, members were deployed in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa and Dnipropetrovsk. Programme of the DelegatIon In the framework of the International Election Observation Mission, the EP Delegation cooperated with the Delegation of the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities, headed by Ms Gudrun Mosler-Törnström (Austria), while the OSCE/ODIHR long-term Election Observation Mission headed by Tana de Zulueta (Italy). The cooperation with the OSCE/ODIHR and the Congress went as usual and a compromise on the joint statement was reached (see annex B). Due to the fact that only two parliamentary delegations were present to observe the local elections, and had rather different expectations as regards meetings to be organised, it was agreed between all parties to limit the joint programme to a briefing by the core team of the OSCE/ODIHR. -

1400 Mb/S +156 Kanałów

Kosmiczna prędkość Pakiet 1400 Mb/s +156 Kanałów Internet Abonament miesięcznie oszczędzasz 149 PLN 149 PLN Predkość wysyłania danych do 1 400 Mb/s Predkość pobierania danych do 1 400 Mb/s Opłata aktywacyjna* 1PLN* / 199 PLN** Okres obowiązywania umowy 24 msc Limit pobierania danych brak Sieć niezależna od łącza telefonicznego w ramach pakietu Dzierżawa routera bezpłatnie Telewizja 2X2 TV HD Disney HD Food Network Novela HD 4Fun Dance Disney-Junior France 24 EN Nowa TV HD 4Fun Gold Hits Disney-XD France 24 FR nSport+ HD 4Fun TV Domo+ HD Gametoon HD Nuta.TV Adventure TV DuckTV-HD HGTV HD Nuta TV HD Adventure TV HD Eleven-Extra Investigation Discovery HD Paramount Channel AleKino+ HD Eleven-HD iTVRegion Planete+ HD Animal Planet HD Eleven-Sport-HD Kino Polska HD Polonia 1 ATM Rozrywka Eska Rock TV (Hip Hop TV) Kino Polska Muzyka Polo TV AXN HD Eska TV Extra HD Kino-TV Polsat 2 HD Belsat TV Eska TV HD Kuchnia+ HD Polsat Cafe HD Comedy-Central-HD ETV Mango 24 Polsat Doku HD Disco Polo Music Eurosport 1 HD Metro TV Polsat Film HD Discovery Channel HD Eurosport 2 HD Metro TV HD Polsat HD Discovery Historia Filmbox Extra HD MiniMini+ HD Polsat Jim Jam Discovery Life Filmbox Family MTV HD Polsat Music HD Discovery Science HD Filmbox Premium HD Nickelodeon Polsat News 2 Discovery Turbo Xtra HD Fokus TV HD Novela Polsat News HD DG-NET S.A. ul. Graniczna 34 41-300 Dąbrowa Górnicza NIP: 629 247 88 45 [email protected] Kosmiczna prędkość Pakiet Polsat Play HD TeleToon+ HD TVP 2 HD TVR HD Polsat Romans TLC HD TVP3 Białystok TVS HD Polsat Sport Extra -

Druk Nr 294 1. „Sprawozdanie Krajowej Rady Radiofonii I

Druk nr 294 Warszawa, 30 marca 2012 r. SEJM RZECZYPOSPOLITEJ POLSKIEJ VII kadencja Przewodniczący Krajowej Rady Radiofonii i Telewizji KRRiT-070-14/020/12 Pani Ewa Kopacz Marszałek Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej Szanowna Pani Marszałek W związku z art. 12 ust. 1 i 2 ustawy z 29 grudnia 1992 roku a radiofonii i telewizji, w załączeniu uprzejmie przekazuję następujące dokumenty, przyjęte przez Krajową Radę Radiofonii i Telewizji, uchwałami Nr 66/2012 z 20 marca oraz 67/2012 z 23 marca bieżącego roku: 1. „Sprawozdanie Krajowej Rady Radiofonii i Telewizji z działalności w 2011 roku”; 2. „Informacja o podstawowych problemach radiofonii i telewizji w 2011 roku”. Uprzejmie proszę Panią Marszałek o przyjęcie i udostępnienie Paniom i Panom Posłom powyższych dokumentów. Wraz z powyższą, kieruję również prośbę, aby zechciała Pani Marszałek rozważyć możliwość przekazania dokumentacji sprawozdawczej KRRiT w wydruku kolorowym z uwagi na liczne wykresy oraz mapy. Będę za taką decyzję szczerze zobowiązany. Z poważaniem (-) Jan Dworak SPRAWOZDANIE KRAJOWEJ RADY RADIOFONII I TELEWIZJI Z DZIAŁALNOŚCI W 2011 ROKU KRAJOWA RADA RADIOFONII I TELEWIZJI, WARSZAWA MARZEC 2012 R. Krajowa Rada Radiofonii i Telewizji UCHWAŁA Nr 66/2012 z dnia 20 marca 2012 roku Na podstawie art. 9 ust. 1 w związku z art. 12 ust. 1 i 2 ustawy z dnia 29 grudnia 1992 roku o radiofonii i telewizji (Dz.U. z 2011 r. Nr 43 poz. 226 z późn. zm.) Krajowa Rada Radiofonii i Telewizji postanawia 1. Przyjąć Sprawozdanie KRRiT z działalności w 2011 roku, stanowiące załącznik do uchwały. 2. Przedstawić Sprawozdanie KRRiT z działalności w 2011 roku: - Sejmowi RP, - Senatowi RP, - Prezydentowi RP. -

1A Okladka Wschod Europy DRUKARNIA Nowa.Cdr

Vol 3, No 2, 2017 Vol 100 Vol 3, No 2, 2017 100 95 ISSN 2450-4866 95 75 75 25 25 5 5 0 0 100 100 95 95 75 75 ISSN 2450-4866 25 25 5 5 0 0 Igor Barygin (Sankt Petersburg), Igor Cependa (Iwano-Frankowsk) Grzbiet Prof. dr hab. Nodar Belkanija (Tbilisi, Gruzja) Vol 3, No 2, 2017 Prof. dr hab. Igor Cependa (Iwano-Frankowsk, Ukraina) Henryk Gmiterek (Lublin), Jan Holzer (Brno) Wschód Europy Восток Европы Prof. dr hab. Henryk Gmiterek (Lublin, Polska) Larysa Leszczenko (Wrocław), Wałerij Kopijka (Kijów) East of Europe Prof. dr hab. Aleksandra Głuchowa (Woroneż, Rosja) Wiktor Szadurski (Mińsk), Zachar Szybieka (Tel Awiw) Okładka Vol 3, No 2, 2017 Prof. dr hab. Jan Holzer (Brno, Czechy) Konrad Zieliński (Lublin) Wschód Europy. Studia humanistyczno-społeczne Восток Европы. Гуманитарно-общественные исследования Dr hab., prof. nadzw. Agnieszka Legucka (Warszawa, Polska) East of Europe. Humanities and social studies ISNN: 2450-4866 Prof. dr hab. Wałerij Kopijka (Kijów, Ukraina) Prof. dr hab. Wiktor Szadurski (Mińsk, Białoruś) Walenty Baluk (redaktor naczelny), Eleonora Kirwiel (sekretarz) Strona przedtytułowa Wschód Europy. Studia humanistyczno-społeczne Prof. dr hab. Zachar Szybieka (Tel Awiw, Izrael) Grzegorz Janusz, Jerzy Garbiński, Wojciech Sokół, Ireneusz Topolski Strona kontrtytułowa Prof. dr hab. Konrad Zieliński (Lublin, Polska) Prof. dr hab. Walenty Baluk (redaktor naczelny) Rada Naukowa Dr Eleonora Kirwiel (sekretarz) Prof. dr hab. Nodar Belkanija (Tbilisi, Gruzja) Prof. dr hab. Grzegorz Janusz Prof. dr hab. Igor Cependa (Iwano-Frankowsk, Ukraina) Dr hab. prof. Jerzy Garbiński Prof. dr hab. Henryk Gmiterek (Lublin, Polska) Dr hab. prof. Wojciech Sokół Prof. dr hab. -

Stacje Ogólne I Tematyczne Polskiej Telewizji Z Perspektywy Genologii Lingwistycznej

Stacje ogólne i tematyczne polskiej telewizji z perspektywy genologii lingwistycznej Aleksandra Kalisz Stacje ogólne i tematyczne polskiej telewizji z perspektywy genologii lingwistycznej Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego • Katowice 2019 Redaktor serii: Językoznawstwo Polonistyczne Mirosława Siuciak Recenzentka Katarzyna Jachimowska Spis treści Wstęp 7 Polska telewizja w badaniach językoznawczych Dotychczasowy stan badań nad telewizją 14 Narzędzia i metody pracy 30 Genologia lingwistyczna 31 Tekstologia 37 Komunikologia 40 Językowy obraz świata 44 Mediolingwistyka 47 Od telektroskopu do telewizji cyfrowej. Przemiany w polskiej telewizji Historia polskiej telewizji 54 Ramówka – klucz do analizy stacji telewizyjnych 67 Programy rodzime a programy licencjonowane 74 Telewizja tematyczna – próba zdefiniowania zjawiska 77 Analiza ramówki wybranych stacji telewizyjnych pod względem genologicznym Ramówka poszczególnych stacji telewizyjnych 83 TVP i jej stacje tematyczne 84 Polsat i jego stacje tematyczne 92 TVN i jego stacje tematyczne 99 Analiza tekstologiczna wybranych programów telewizyjnych Charakterystyka wybranych gatunków i analizy tekstologiczne ich realizacji 109 Różne odsłony poradnika telewizyjnego 112 Teleturniej 124 Telewizja tematyczna – miejsce powstawania plotki 129 Telewizja – przestrzeń występowania osobliwości genologicznych 137 6 Spis treści Znaczenie stacji tematycznych dla polskiej telewizji Odmasowienie środków masowego przekazu 141 Telewizja w nowych mediach 146 Zakończenie 149 Bibliografia 153 Netografia 159 Summary 161