Well Managed Highway Liability Risk FOREWORD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Law and Civil Liberties ISBN 978-1-137-54503-9.Indd

Copyrighted material – 9781137545039 Contents Preface . v Magna Carta (1215) . 1 The Bill of Rights (1688) . 2 The Act of Settlement (1700) . 5 Union with Scotland Act 1706 . 6 Official Secrets Act 1911 . 7 Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949 . 8 Official Secrets Act 1920 . 10 The Statute of Westminster 1931 . 11 Public Order Act 1936 . 12 Statutory Instruments Act 1946 . 13 Crown Proceedings Act 1947 . 14 Life Peerages Act 1958 . 16 Obscene Publications Act 1959 . 17 Parliamentary Commissioner Act 1967 . 19 European Communities Act 1972 . 24 Local Government Act 1972 . 26 Local Government Act 1974 . 30 House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975 . 36 Ministerial and Other Salaries Act 1975 . 38 Highways Act 1980 . 39 Senior Courts Act 1981 . 39 Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 . 45 Public Order Act 1986 . 82 Official Secrets Act 1989 . 90 Security Service Act 1989 . 96 Intelligence Services Act 1994 . 97 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 . 100 Police Act 1996 . 104 Police Act 1997 . 106 Human Rights Act 1998 . 110 Scotland Act 1998 . 116 Northern Ireland Act 1998 . 121 House of Lords Act 1999 . 126 Freedom of Information Act 2000 . 126 Terrorism Act 2000 . 141 Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 . 152 Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 . 158 Police Reform Act 2002 . 159 Constitutional Reform Act 2005 . 179 Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 . 187 Equality Act 2006 . 193 Terrorism Act 2006 . 196 Government of Wales Act 2006 . 204 Serious Crime Act 2007 . 209 UK Borders Act 2007 . 212 Parliamentary Standards Act 2009 . 213 Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 . 218 European Union Act 2011 . -

Sweet & Maxwell

SWEET & MAXWELL PROFESSIONAL CATALOGUE 2014 SWEET & MAXWELL REUTERS/Neil Hall REUTERS/Neil LEGAL SOLUTIONS FROM THOMSON REUTERS We deliver best-of-class legal solutions to help you practise LEGAL RESEARCH, NEWS AND BUSINESS INFORMATION the law, manage your organisation and help you and your Westlaw UK | Westlaw International business grow. LEGAL UPDATES & CURRENCY Lawtel Our solutions include Sweet & Maxwell commentary, Practical Law, Westlaw UK, Lawtel, and a series of software solutions LEGAL KNOW-HOW Practical Law including Serengeti, Solcara and Thomson Reuters Elite. FEDERATED SEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT Intelligently connect your work and your world with our Solcara content, expertise and technologies. TRAINING AND EDUCATION Legal Conferences and Webinars See a better way forward at thomsonreuters.com/ukirelandlegal IN-HOUSE LEGAL DEPARTMENT MANAGEMENT Serengeti LAW FIRM MANAGEMENT Thomson Reuters Elite LAW BOOKS Sweet & Maxwell BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT & MARKETING FindLaw WELCOME TO THE SWEET & MAXWELL 2014 PROFESSIONAL CATALOGUE Great content, delivered flexibly. It’s at the heart of what we do at Thomson Reuters. Our Sweet & Maxwell commentary titles, used by thousands of legal professionals every day, bring clarity to complex matters and give you the confidence to make the big decisions. This year’s catalogue is packed with the most authoritative legal voices, tackling the issues of today. Among the hundreds of specialist titles, you can look forward to new editions of: The White Book Archbold: Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice Sealy & Milman: Annotated Guide to the Insolvency Legislation The Mental Health Act Manual Clerk & Lindsell on Torts McGregor on Damages Benjamin’s Sale of Goods Hudson’s Building and Engineering Contracts View our complete catalogue at sweetandmaxwell.co.uk With our professional-grade eBook app, Thomson Reuters Proview™, you can experience these trusted practitioner texts in entirely new ways on the iPad, Mac, PC and in beta on Android tablets. -

Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007

Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 CHAPTER 15 Explanatory Notes have been produced to assist in the understanding of this Act and are available separately £32·00 Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 CHAPTER 15 CONTENTS PART 1 TRIBUNALS AND INQUIRIES CHAPTER 1 TRIBUNAL JUDICIARY: INDEPENDENCE AND SENIOR PRESIDENT 1 Independence of tribunal judiciary 2 Senior President of Tribunals CHAPTER 2 FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL AND UPPER TRIBUNAL Establishment 3 The First-tier Tribunal and the Upper Tribunal Members and composition of tribunals 4 Judges and other members of the First-tier Tribunal 5 Judges and other members of the Upper Tribunal 6 Certain judges who are also judges of First-tier Tribunal and Upper Tribunal 7 Chambers: jurisdiction and Presidents 8 Senior President of Tribunals: power to delegate Review of decisions and appeals 9 Review of decision of First-tier Tribunal ii Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (c. 15) 10 Review of decision of Upper Tribunal 11 Right to appeal to Upper Tribunal 12 Proceedings on appeal to Upper Tribunal 13 Right to appeal to Court of Appeal etc. 14 Proceedings on appeal to Court of Appeal etc. "Judicial review" 15 Upper Tribunal’s “judicial review” jurisdiction 16 Application for relief under section 15(1) 17 Quashing orders under section 15(1): supplementary provision 18 Limits of jurisdiction under section 15(1) 19 Transfer of judicial review applications from High Court 20 Transfer of judicial review applications from the Court of Session 21 Upper Tribunal’s “judicial review” jurisdiction: -

General Scheme of Delegation to Officers

PART 3 3.2 SCHEME OF DELEGATION TO OFFICERS 1 Revised as at Council 22/10/2020 INDEX Page No. INTRODUCTION AND POWERS TO THE CHIEF 3 EXECUTIVE AND ALL DIRECTORS CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S 11 RESOURCES 17 SOCIAL CARE, HEALTH AND HOUSING 27 REGENERATION 61 TECHNICAL SERVICES 67 EDUCATION AND CHILDREN’S SERVICES 73 2 Revised as at Council 22/10/2020 1. INTRODUCTION This Scheme of Delegation is maintained under Section 100G of the Local Government Act 1972 and lists the functions that have been delegated to particular officers by either the Council or the Executive Board. These functions are delegated to officers by the Council under Sections 101 and 151 of the Local Government Act 1972 and by the Executive Board under Section 15 of the Local Government Act 2000. All Directors are authorised to make arrangements for the proper administration of the functions falling within their responsibility. 1.1 The officers described in this Scheme may authorise officers in their department/service area to exercise on their behalf, functions delegated to them. Any decisions taken under this authority shall remain the responsibility of the officer described in this Scheme and must be taken in the name of that officer, who shall remain accountable and responsible for such decisions. Each department shall maintain a record of these further delegations. 1.2 The Scheme delegates powers and duties within broad functional descriptions and includes powers and duties under all legislation present and future within those descriptions. Any reference to a specific statute includes any statutory extension or modification or re-enactment of such statute and any regulations, orders or bylaws made there under. -

Guide on Firearms Licensing Law

Guide on Firearms Licensing Law April 2016 Contents 1. An overview – frequently asked questions on firearms licensing .......................................... 3 2. Definition and classification of firearms and ammunition ...................................................... 6 3. Prohibited weapons and ammunition .................................................................................. 17 4. Expanding ammunition ........................................................................................................ 27 5. Restrictions on the possession, handling and distribution of firearms and ammunition .... 29 6. Exemptions from the requirement to hold a certificate ....................................................... 36 7. Young persons ..................................................................................................................... 47 8. Antique firearms ................................................................................................................... 53 9. Historic handguns ................................................................................................................ 56 10. Firearm certificate procedure ............................................................................................... 69 11. Shotgun certificate procedure ............................................................................................. 84 12. Assessing suitability ............................................................................................................ -

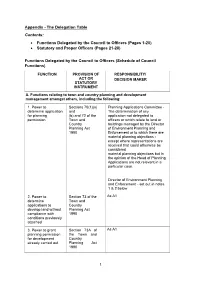

Functions Delegated by the Council to Officers (Pages 1-20) • Statutory and Proper Officers (Pages 21-28)

Appendix - The Delegation Table Contents: • Functions Delegated by the Council to Officers (Pages 1-20) • Statutory and Proper Officers (Pages 21-28) Functions Delegated by the Council to Officers (Schedule of Council Functions) FUNCTION PROVISION OF RESPONSIBILITY/ ACT OR DECISION MAKER STATUTORY INSTRUMENT A. Functions relating to town and country planning and development management amongst others, including the following: 1. Power to Sections 70(1)(a) Planning Applications Committee - determine application and The determination of any for planning (b) and 72 of the application not delegated to permission Town and officers or which relate to land or Country buildings managed by the Director Planning Act of Environment Planning and 1990 Enforcement or to which there are material planning objections - except where representations are received that could otherwise be considered material planning objections but in the opinion of the Head of Planning Applications are not relevant in a particular case. Director of Environment Planning and Enforcement - set out in notes 1 & 2 below 2. Power to Section 73 of the As A1 determine Town and applications to Country develop land without Planning Act compliance with 1990 conditions previously attached 3. Power to grant Section 73A of As A1 planning permission the Town and for development Country already carried out Planning Act 1990 1 4. Power to Section 316 of the As A1. determine application Town and Country for planning Planning Act 1990 permission made by and the Town and a local authority, Country Planning alone or jointly with General another person Regulations 1992 (S.I. 1992/1492) (and subsequent amendments and regulations). -

Modernising English Criminal Legislation 1267-1970

Public Administration Research; Vol. 6, No. 1; 2017 ISSN 1927-517x E-ISSN 1927-5188 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Modernising English Criminal Legislation 1267-1970 Graham McBain1,2 1 Peterhouse, Cambridge, UK 2 Harvard Law School, USA Correspondence: Graham McBain, 21 Millmead Terrace, Guildford, Surrey GU2 4AT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 2, 2017 Accepted: April 19, 2017 Online Published: April 27, 2017 doi:10.5539/par.v6n1p53 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/par.v6n1p53 1. INTRODUCTION English criminal - and criminal procedure - legislation is in a parlous state. Presently, there are some 286 Acts covering criminal law and criminal procedure with the former comprising c.155 Acts. Therefore, it is unsurprising that Judge CJ, in his book, The Safest Shield (2015), described the current volume of criminal legislation as 'suffocating'. 1 If one considers all legislation extant from 1267 - 1925 (see Appendix A) a considerable quantity comprises criminal law and criminal procedure - most of which is (likely) obsolete.2 Given this, the purpose of this article is to look at criminal legislation in the period 1267-1970 as well as criminal procedure legislation in the period 1267-1925. Its conclusions are simple: (a) the Law Commission should review all criminal legislation pre-1890 as well as a few pieces thereafter (see Appendix B). It should also review (likely) obsolete common law crimes (see Appendix C); (b) at the same time, the Ministry of Justice (or Home Office) should consolidate all criminal legislation post-1890 into 4 Crime Acts.3 These should deal with: (a) Sex crimes; (b) Public order crimes; (c) Crimes against the person; (d) Property and financial crimes (see 7). -

Scheme of Delegated Powers

Part 3 Responsibility of Functions – Scheme of Delegated Powers RESPONSIBILITY FOR FUNCTIONS DELEGATED POWERS GENERAL The Local Authorities (Functions and Responsibilities) (England) Regulations 2000 (as amended) give effect to section 13 of the Local Government Act 2000 by specifying: - (a) which functions are not to be the responsibility of the Executive (Cabinet); as specified in Schedule 1 to the Local Authorities (Functions and Responsibilities) (England) Regulations 2000 and as detailed in the Appendix to this part of the Constitution. (b) functions which may (but need not) be the responsibility of the Executive (Cabinet) (local choice functions); (c) which are to some extent the responsibility of the Executive. All other functions not so specified are to be the responsibility of the Executive. Every decision of the Cabinet, a Portfolio Holder, Committee, Sub-Committee, Working Party or Officer under delegated powers shall comply with the Council’s Constitution and in particular with its Budget and Policy Framework, Council Procedure Rules, Financial Procedure Rules and Procurement Procedure Rules and any expenditure involved is subject to such compliance. 1. RESPONSIBILITY FOR LOCAL CHOICE FUNCTIONS Local Choice functions are those, which may (but need not) be the responsibility of the Cabinet. Schedule 1 of Part 3 of the Constitution details the responsibility for those local choice functions as set out in Schedule 2 to the Local Authorities (Functions and Responsibilities) (England) Regulations 2000, as determined by the Council. 2. RESPONSIBILITY FOR COUNCIL (NON-EXECUTIVE) FUNCTIONS The roles and responsibilities of full Council are set out in Article 4 of the Constitution. The specific functions set out in Schedule 1 to the Local Authorities (Functions and Responsibilities) (England) Regulations 2000 which are retained for determination by full Council are set out in Schedule 2. -

Act 1986 CHAPTER 12 ARRANGEMENT of SECTIONS

Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1986 CHAPTER 12 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section Repeals and associated amendments. 2. Extent. 3. Short title. SCHEDULE 1—Repeals. Part I — Administration of Justice. Part II — Agriculture. Part III — Finance. Part IV — Imports and Exports. Part V — Industrial Relations. Part VI — Intellectual Property. Part VII — Local Government. Part VIII — Medicine and Health Services. Part IX — Overseas Jurisdiction. Part X — Parliamentary and Constitutional Pro- visions. Part XI — Shipping, Harbours and Fisheries. Part XII — Subordinate Legislation Procedure. Part XIII — Miscellaneous. SCHEDULE 2 —Consequential Provisions. A c.12 ELIZABETH II Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1986 1986 CHAPTER 12 An Act to promote the reform of the statute law by the repeal, in accordance with recommendations of the Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission, of certain enactments which (except in so far as their effect is preserved) are no longer of practical utility, and to make other provision in connection with the repeal of those enactments. [2nd May 1986] E IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and B Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— L—(1) The enactments mentioned in Schedule 1 to this Act Repeals and are hereby repealed to the extent specified in the third column of associated that Schedule. amendments. (2) Schedule 2 to this Act shall have effect. 2.—(l) This Act extends to Northern Ireland. Extent. (2) Any amendment or repeal by this Act of an enactment which extends to the Channel Islands or the Isle of Man shall also extend there. -

Highways Act 1980

Highways Act 1980 CHAPTER 66 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I HIGHWAY AUTHORITIES AND AGREEMENTS BETWEEN AUTHORITIES Highway authorities Section 1. Highway authorities : general provision. 2. Highway authority for road which ceases to be a trunk road. 3. Highway authority for approaches to and parts of certain bridges. Agreements between authorities 4. Agreement for exercise by Minister of certain functions of local highway authority as respects highway affected by construction, etc. of trunk road. 5. Agreement for local highway authority to maintain and improve certain highways constructed or to be con- structed by Minister. 6. Delegation etc. of functions with respect to trunk roads. 7. Delegation etc. of functions with respect to metropolitan roads. 8. Agreements between local highway authorities for doing of certain works. 9. Seconding of staff etc. PART II TRUNK RoADS, CLASsIFIED RoADS, METROPOLITAN ROADS, SPECIAL ROADS Trunk roads 10. General provision as to trunk roads. 11. Local and private Act functions with respect to trunk roads. Classified roads 12. General provision as to principal and classified roads. 13. Power to change designation of principal roads. A ii c. 66 Highways Act 1980 Powers as respects roads that cross or join trunk roads or classified roads Section 14. Powers as respects roads that cross or join trunk or classified roads. Metropolitan roads 15. General provision as to metropolitan roads. Special roads 16. General provision as to special roads. 17. Classification of traffic for purposes of special roads. 18. Supplementary orders relating to special roads. 19. Certain special roads and other highways to become trunk roads. 20. Restriction on laying of apparatus etc. -

Legislation and Regulations

STATUTES HISTORICALY SIGNIFICANT ENGLISH STATUTES SIGNIFICANT U.S. FEDERAL LEGISLATION AND REGULATIONS STATUTORY REFERENCES IN THE ENCYCLOPEDIA ENGLISH STATUTES A B C D E F G H I-K L M N O P R S T U-Z US STATUTES Public Acts and Codes Uniform Commercial Code Annotated (USCA) State Codes AUSTRALIAN STATUTES CANADIAN STATUTES & CODES NEW ZEALAND STATUTES FRENCH CODES & LEGISLATION French Civil Code Other French Codes French Laws & Decrees OTHER CODES 1 back to the top STATUTES HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT ENGLISH STATUTES De Donis Conditionalibus 1285 ................................................................................................................................. 5 Statute of Quia Emptores 1290 ................................................................................................................................ 5 Statute of Uses 1536.................................................................................................................................................. 5 Statute of Frauds 1676 ............................................................................................................................................. 6 SIGNIFICANT SIGNIFICANT ENGLISH STATUTES Housing Acts ................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Land Compensation Acts ........................................................................................................................................ -

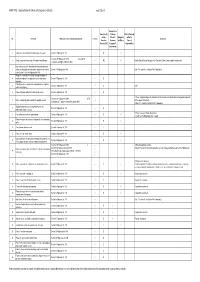

Highway Network Scheme of Delegation and Duties April 2021 V2

HNMP TA02 ‐ Highway Network Scheme of Delegation and Duties April 2021 V2 Delegation to Executive (E) Strategic District, Borough or Non- Director - Delegation or Parish No. Function Provision of Act or Statutory Instrument In Force Comments Executive Economy, to Officer Council Function (NE) Transport & Responsibility Environment 1 Powers to create footpaths and bridleways by agreement Section 25 Highways Act 1980 NE 1) Section 26 Highways Act 1980 2) Section 58 2 Compulsory powers for creation of footpaths and bridleways NE Enables Natural England to apply to the Secretary of State to make a public footpath order Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 Duty to keep register of information with respect to maps and 3 statements deposited and declarations lodged with the Council Section 31A Highways Act 1980 Duty - The Council's Constitution Part 3 Appendix 2 under Section 31(6) of the Highways Act 1980 Response to a dedication either by certifying acceptance or 4 making a complaint to a magistrates' court to resist such a Section 37 Highways Act 1980 E dedication Authority to make a complaint by resisting dedication of publicly 5 Section 37 Highways Act 1980 E Cabco maintainable Highway 6 Power of Highway Authorities to adopt by agreement Section 38 Highways Act 1980 E 1) Power to impose charges, in connection with the clearance of accident debris, on the person responsible 1) Section 41 Highways Act 1980 2) The 7 Duty to maintain highways maintainable at public expense for the deposit of the debris Local Authority (Transport Charges)