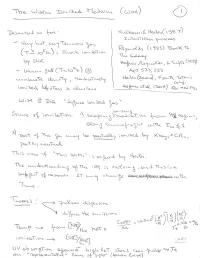

The Black Hole Mass Function Derived from Local Spiral Galaxies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fourier Dissection of Early-Type Galaxy Bars R

The Astronomical Journal, 132:1859Y1876, 2006 November # 2006. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. FOURIER DISSECTION OF EARLY-TYPE GALAXY BARS R. Buta,1 E. Laurikainen,2 H. Salo,2 D. L. Block,3 and J. H. Knapen4 Received 2006 May 4; accepted 2006 July 14 ABSTRACT This paper reports on a near-infrared survey of early-type galaxies designed to provide information on bar strengths, bulges, disks, and bar parameters in a statistically well-defined sample of S0YSa galaxies. Early-type galaxies have the advantage that their bars are relatively free of the effects of dust, star formation, and spiral structure that com- plicate bar studies in later type galaxies. We describe the survey and present results on a detailed analysis of the rela- tive Fourier intensity amplitudes of bars in 26 early-type galaxies. We also evaluate the ‘‘symmetry assumption’’ of these amplitudes with radius, used recently for bar-spiral separation in later type galaxies. The results show a wide variety of radial Fourier profiles of bars, ranging from simple symmetric profiles that can be represented in terms of a single Gaussian component to both symmetric and asymmetric profiles that can be represented by two overlapping Gaussian components. More complicated profiles than these are also found, often due to multiple barlike features including extended ovals or lenses. Based on the gravitational bar torque indicator Qb, double-Gaussian bars are stronger on average than single-Gaussian bars, at least for our small sample. We show that published numerical simulations in which the bar transfers a large amount of angular momentum to the halo can account for many of the observed profiles. -

The X-Ray Emission of Local Luminous Infrared Galaxies⋆

A&A 535, A93 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201117420 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics The X-ray emission of local luminous infrared galaxies M. Pereira-Santaella1, A. Alonso-Herrero1, M. Santos-Lleo2, L. Colina1, E. Jiménez-Bailón3, A. L. Longinotti4, G. H. Rieke5,M.Ward6, and P. Esquej1 1 Departamento de Astrofísica, Centro de Astrobiología, CSIC/INTA, Carretera de Torrejón a Ajalvir, km 4, 28850 Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 2 XMM-Newton Science Operation Centre, European Space Agency, 28691 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain 3 Instituto de Astronomía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Apartado Postal 70-264, 04510 Mexico DF, México 4 MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, NE80-6011, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 5 Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, 933 North Cherry Avenue, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA 6 Department of Physics, Durham University, South Road, Durham, DH1 3LE, UK Received 6 June 2011 / Accepted 5 September 2011 ABSTRACT We study the X-ray emission of a representative sample of 27 local luminous infrared galaxies (LIRGs). The median IR luminosity of our sample is log LIR/L = 11.2, therefore the low-luminosity end of the LIRG class is well represented. We used new XMM-Newton data as well as Chandra and XMM-Newton archive data. The soft X-ray (0.5–2 keV) emission of most of the galaxies (>80%), including LIRGs hosting a Seyfert 2 nucleus, is dominated by star-formation-related processes. These LIRGs follow the star-formation rate (SFR) versus soft X-ray luminosity correlation observed in local starbursts. -

![Arxiv:1210.3628V1 [Astro-Ph.CO] 12 Oct 2012](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3448/arxiv-1210-3628v1-astro-ph-co-12-oct-2012-163448.webp)

Arxiv:1210.3628V1 [Astro-Ph.CO] 12 Oct 2012

To be published in the A.J. Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 08/22/09 EXTENDING THE NEARBY GALAXY HERITAGE WITH WISE: FIRST RESULTS FROM THE WISE ENHANCED RESOLUTION GALAXY ATLAS T.H. Jarrett1,2, F. Masci1, C.W. Tsai1, 5, S. Petty3, M. Cluver4, Roberto J. Assef5,12, D. Benford6, A. Blain7, C. Bridge13, E. Donoso14, P. Eisenhardt5, B. Koribalski8, S. Lake3, James D. Neill13, M. Seibert9, K. Sheth10, S. Stanford11, E. Wright3 Accepted for Publication in the Astronomical Journal ABSTRACT The Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) mapped the entire sky at mid-infrared wavelengths 3.4 µm, 4.6 µm, 12 µm and 22 µm. The mission was primarily designed to extract point sources, leaving resolved and extended sources, for the most part, unexplored. Accordingly, we have begun a dedicated WISE Enhanced Resolution Galaxy Atlas (WERGA) project to fully characterize large, nearby galaxies and produce a legacy image atlas and source catalogue. Here we demonstrate the first results of the WERGA-project for a sample of 17 galaxies, chosen to be of large angular size, diverse morphology, and covering a range in color, stellar mass and star formation. It includes many well- studied galaxies, such as M 51, M 81, M 87, M 83, M 101, IC 342. Photometry and surface brightness decomposition is carried out after special super-resolution processing, achieving spatial resolutions similar to that of Spitzer -IRAC. The enhanced resolution method is summarized in the first paper of this two part series. In this second work, we present WISE, Spitzer and GALEX photometric and characterization measurements for the sample galaxies, combining the measurements to study the global properties. -

The SBF Survey of Galaxy Distances. I. Sample Selection, Photometric

TheSBFSurveyofGalaxyDistances.I. Sample Selection, Photometric Calibration, and the Hubble Constant1 John L. Tonry2 and John P. Blakeslee2 Physics Dept. Room 6-204, MIT, Cambridge, MA 02139; Edward A. Ajhar2 Kitt Peak National Observatory, National Optical Astronomy Observatories, P.O. Box 26732 Tucson, AZ 85726; Alan Dressler Carnegie Observatories, 813 Santa Barbara St., Pasadena, CA 91101 ABSTRACT We describe a program of surface brightness fluctuation (SBF) measurements for determining galaxy distances. This paper presents the photometric calibration of our sample and of SBF in general. Basing our zero point on observations of Cepheid variable stars we find that the absolute SBF magnitude in the Kron-Cousins I band correlates well with the mean (V −I)0 color of a galaxy according to M I =(−1.74 ± 0.07) + (4.5 ± 0.25) [(V −I)0 − 1.15] for 1.0 < (V −I) < 1.3. This agrees well with theoretical estimates from stellar popula- tion models. Comparisons between SBF distances and a variety of other estimators, including Cepheid variable stars, the Planetary Nebula Luminosity Function (PNLF), Tully-Fisher (TF), Dn−σ, SNII, and SNIa, demonstrate that the calibration of SBF is universally valid and that SBF error estimates are accurate. The zero point given by Cepheids, PNLF, TF (both calibrated using Cepheids), and SNII is in units of Mpc; the zero point given by TF (referenced to a distant frame), Dn−σ, and SNIa is in terms of a Hubble expan- sion velocity expressed in km/s. Tying together these two zero points yields a Hubble constant of H0 =81±6 km/s/Mpc. -

115 Abell Galaxy Cluster # 373

WINTER Medium-scope challenges 271 # # 115 Abell Galaxy Cluster # 373 Target Type RA Dec. Constellation Magnitude Size Chart AGCS 373 Galaxy cluster 03 38.5 –35 27.0 Fornax – 180 ′ 5.22 Chart 5.22 Abell Galaxy Cluster (South) 373 272 Cosmic Challenge WINTER Nestled in the southeast corner of the dim early winter western suburbs. Deep photographs reveal that NGC constellation Fornax, adjacent to the distinctive triangle 1316 contains many dust clouds and is surrounded by a formed by 6th-magnitude Chi-1 ( 1), Chi-2 ( 2), and complex envelope of faint material, several loops of Chi-3 ( 3) Fornacis, is an attractive cluster of galaxies which appear to engulf a smaller galaxy, NGC 1317, 6 ′ known as Abell Galaxy Cluster – Southern Supplement to the north. Astronomers consider this to be a case of (AGCS) 373. In addition to his research that led to the galactic cannibalism, with the larger NGC 1316 discovery of more than 80 new planetary nebulae in the devouring its smaller companion. The merger is further 1950s, George Abell also examined the overall structure signaled by strong radio emissions being telegraphed of the universe. He did so by studying and cataloging from the scene. 2,712 galaxy clusters that had been captured on the In my 8-inch reflector, NGC 1316 appears as a then-new National Geographic Society–Palomar bright, slightly oval disk with a distinctly brighter Observatory Sky Survey taken with the 48-inch Samuel nucleus. NGC 1317, about 12th magnitude and 2 ′ Oschin Schmidt camera at Palomar Observatory. In across, is visible in a 6-inch scope, although averted 1958, he published the results of his study as a paper vision may be needed to pick it out. -

![Arxiv:2001.00331V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 27 Feb 2020 Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5406/arxiv-2001-00331v2-astro-ph-ga-27-feb-2020-et-al-635406.webp)

Arxiv:2001.00331V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 27 Feb 2020 Et Al

Draft version February 28, 2020 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX62 The Carnegie-Irvine Galaxy Survey. IX. Classification of Bulge Types and Statistical Properties of Pseudo Bulges Hua Gao (高f),1, 2 Luis C. Ho,2, 1 Aaron J. Barth,3 and Zhao-Yu Li4 1Department of Astronomy, School of Physics, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China 2Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China 3Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California at Irvine, 4129 Frederick Reines Hall, Irvine, CA 92697-4575, USA 4Department of Astronomy, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200240, China ABSTRACT We study the statistical properties of 320 bulges of disk galaxies in the Carnegie-Irvine Galaxy Survey, using robust structural parameters of galaxies derived from image fitting. We apply the Kormendy relation to classify classical and pseudo bulges and characterize bulge dichotomy with respect to bulge structural properties and physical properties of host galaxies. We confirm previous findings that pseudo bulges on average have smaller S´ersic indices, smaller bulge-to-total ratios, and fainter surface brightnesses when compared with classical bulges. Our sizable sample statistically shows that pseudo bulges are more intrinsically flattened than classical bulges. Pseudo bulges are most frequent (incidence & 80%) in late-type spirals (later than Sc). Our measurements support the picture in which pseudo bulges arose from star formation induced by inflowing gas, while classical bulges were born out of violent processes such as mergers and coalescence of clumps. We reveal differences with the literature that warrant attention: (1) the bimodal distribution of S´ersicindices presented by previous studies is not reproduced in our study; (2) classical and pseudo bulges have similar relative bulge sizes; and (3) the pseudo bulge fraction is considerably smaller in early-type disks compared with previous studies based on one-dimensional surface brightness profile fitting. -

Warm Ionized Medium.Pdf

IVie. UJc^u-^ -Xo^^hl^ M^ckovx^ (covWVJ i- (o l<-) y SL-ock, io-^.lc^Vv^v A^-3 5"2?>, 2-Z3 \truvi A ^ TV, ^"4? (^ ^& ^^^ . Xr v^^ cU^c^^ £ cuTU. T- •*_. <r**VZ lfcS<B3 _\.fcS*i° ? \ i>\ \ ^-QA vv£W >jirv 3 <QD o ck: o-A- \^ cL^tv^*> c ^O - i. ; &*&>} ;w*.o _- _e^ - \r*e ^ 6t^M^^^ ^ tm t* ^*si**o uor^c- 2.\<^c c^.-vw^— <r*,> « O.C25 V O.ovb <a o— ^^-, LOvH E. K^ ', -»i -^ K^Qj&ff**'^ V"W. £^Q V^ J»S^\ C/V^ C,awvXv^^ >jl!laa.<A To oq ~TW ReM a^<£A* GLg>^ rto^wu^ C*o*«0 ; c^^rf^ , tV*\V^ ^"T^V^- ^^ z/zrr^ Lo^ (VV°'Z' AA o = e.fnA>«-1 » eV% i-'l »t- <T^ <r"° CJL. s"L^ »Wa4^ ^ A-»^f\JCL p-^OOe^ ©aj<oa(2o c^L 4-cJ5t^^ CI) <^©a^ • #0 ^T^a_j f^TU ^e^^cy <-(\eJU.s ~ ^^1 ;^.*pU£w^__ S~\ - 2 ^ /u^ lA erf T^ T^ *occ^fL HlT^^ T- <Lx^«^ 3Xj^ WoT A<S^7 "^v*-*-^^*&b ^vx.cUv-c^CA^ ^TW*n ^^ %^^>^e^s^N.^ . VW^ C^^o) Jh*~** C«^j ,vc Qa-^j—^JT '. 'p'^a-^^ovAJL VQ©£-4>>~-Cc . oJ vTtv &-a^ < 1i s 2T- t^H ^%U= o.ofe cm!3 = Woo K <u^ } ^^r A- uio^ -^ojt-v. Haj&la, OKiK CotOH , TUcis is* puAcT^i To occcaw. (—- TUa_ HeVc^-GV^VU^ CO\f\ at the UR des an distri- ^dium, 5 basic those atures solar *ate is stend- •out I , e.g., )f ion- log Ih. -

WALLABY Pre-Pilot Survey: Two Dark Clouds in the Vicinity of NGC 1395

University of Texas Rio Grande Valley ScholarWorks @ UTRGV Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications and Presentations College of Sciences 2021 WALLABY pre-pilot survey: Two dark clouds in the vicinity of NGC 1395 O. I. Wong University of Western Australia A. R. H. Stevens B. Q. For University of Western Australia Tobias Westmeier M. Dixon See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/pa_fac Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons, and the Physics Commons Recommended Citation O I Wong, A R H Stevens, B-Q For, T Westmeier, M Dixon, S-H Oh, G I G Józsa, T N Reynolds, K Lee-Waddell, J Román, L Verdes-Montenegro, H M Courtois, D Pomarède, C Murugeshan, M T Whiting, K Bekki, F Bigiel, A Bosma, B Catinella, H Dénes, A Elagali, B W Holwerda, P Kamphuis, V A Kilborn, D Kleiner, B S Koribalski, F Lelli, J P Madrid, K B W McQuinn, A Popping, J Rhee, S Roychowdhury, T C Scott, C Sengupta, K Spekkens, L Staveley-Smith, B P Wakker, WALLABY pre-pilot survey: Two dark clouds in the vicinity of NGC 1395, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 2021;, stab2262, https://doi.org/10.1093/ mnras/stab2262 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Sciences at ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fece, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 A STUDY OF ATTENUATION EFFECTS IN HIGHLY INCLINED SPIRAL GALAXIES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Leslie E. -

Revealing Hidden Substructures in the $ M {BH} $-$\Sigma $ Diagram

Draft version November 14, 2019 A Typeset using L TEX twocolumn style in AASTeX63 Revealing Hidden Substructures in the MBH –σ Diagram, and Refining the Bend in the L–σ Relation Nandini Sahu,1,2 Alister W. Graham2 And Benjamin L. Davis2 — 1OzGrav-Swinburne, Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC 3122, Australia 2Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC 3122, Australia (Accepted 2019 October 22, by The Astrophysical Journal) ABSTRACT Using 145 early- and late-type galaxies (ETGs and LTGs) with directly-measured super-massive black hole masses, MBH , we build upon our previous discoveries that: (i) LTGs, most of which have been 2.16±0.32 alleged to contain a pseudobulge, follow the relation MBH ∝ M∗,sph ; and (ii) the ETG relation 1.27±0.07 1.9±0.2 MBH ∝ M∗,sph is an artifact of ETGs with/without disks following parallel MBH ∝ M∗,sph relations which are offset by an order of magnitude in the MBH -direction. Here, we searched for substructure in the MBH –(central velocity dispersion, σ) diagram using our recently published, multi- component, galaxy decompositions; investigating divisions based on the presence of a depleted stellar core (major dry-merger), a disk (minor wet/dry-merger, gas accretion), or a bar (evolved unstable 5.75±0.34 disk). The S´ersic and core-S´ersic galaxies define two distinct relations: MBH ∝ σ and MBH ∝ 8.64±1.10 σ , with ∆rms|BH = 0.55 and 0.46 dex, respectively. We also report on the consistency with the slopes and bends in the galaxy luminosity (L)–σ relation due to S´ersic and core-S´ersic ETGs, and LTGs which all have S´ersic light-profiles. -

Dissecting the Origin of the Submillimetre Emission in Nearby Galaxies with Herschel and LABOCA

MNRAS 439, 2542–2570 (2014) doi:10.1093/mnras/stu113 Advance Access publication 2014 February 17 Dissecting the origin of the submillimetre emission in nearby galaxies with Herschel and LABOCA M. Galametz,1,2‹ M. Albrecht,3 R. Kennicutt,1 G. Aniano,4 F. Bertoldi,3 D. Calzetti,5 K. V. Croxall,6 D. Dale,7 B. Draine,8 C. Engelbracht,9,10 K. Gordon,11 J. Hinz,9 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/439/3/2542/1092583 by Princeton University user on 02 May 2019 L. K. Hunt,12 A. Kirkpatrick,5 E. Murphy,13 H. Roussel,14 R. A. Skibba,15 F. Walter,16 A. Weiss17 andC.D.Wilson18 1Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK 2European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, D-85748 Garching-bei-Munchen,¨ Germany 3Argelander-Institut fur¨ Astronomie, Abteilung Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hugel¨ 71, D-53121 Bonn, Germany 4Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, Orsay 5Department of Astronomy, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003, USA 6Department of Astronomy, The Ohio State University, 4051 McPherson Laboratory, 140 W 18th Ave., Columbus, OH 43210, USA 7Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071, USA 8Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA 9Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA 10Raytheon Company, 1151 East Hermans Road, Tucson, AZ 85756, USA 11Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 12INAF Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, -

Study of the Existence of Active Galactic Nuclei of the Evolution and Disappearance of the Torus Through X-Rays

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Instituto de Radioastronomía y Astrofísica PhD. in Science (Astrophysics) Advance of doctoral project Study of the existence of Active Galactic Nuclei of the evolution and disappearance of the torus through X-rays PRESENTS: Natalia Osorio Clavijo ADVISOR: Dra. Omaira González Martín June 2021 1 Introduction It has been widely accepted that all galaxies with developed bulges, host a super massive black hole (SMBH), which in some cases is being fed by an accretion disk, causing the liberation of energy of orders up to bolometric luminosities L ∼ 1044 erg s−1. The nuclei of galaxies with such phenomenon are known as active galactic nuclei (AGN), and can emit through all the electromagnetic spectrum. According to the standard model (Urry and Padovani, 1995) AGN are composed by several regions apart from the accretion disk. Such regions are made up from clouds of dust and gas, although their formation and evolution are still under debate. Among the components, we find the SMBH, whose mass can be of the 6 10 order of ∼ 10 − 10 M , the accretion disk, which is responsible for the accretion onto the SMBH and most of the energy released. The temperature of this structure places the peak of emission at opti- cal/UV wavelengths. The broad line region (BLR) is placed beyond the accretion disk and is formed by clouds of gas, with speeds of several thousands of km/s (Davidson and Netzer, 1979), producing the broadening of lines emitted in the optical and infrarred range (e.g., Hα,Hβ, the Paschen series, etc.) This region is surrounded by the torus, a region composed by dust that is heated by the accretion disk up to a few 1000 of K, placing the peak of its emission at infrared wavelengths.