The Warburg Library Classification Scheme in Its Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London's Warburg Institute Launches £14.5M Expansion to Revive

AiA Art News-service London’s Warburg Institute launches £14.5m expansion to revive the 'science of culture' Research centre based on the library of German art historian Aby Warburg plans to open new public spaces in 2022 SIMON TAIT 24th April 2019 12:03 BST Aby Warburg’s library in Hamburg, which was smuggled out of Nazi Germany to London in 1933Courtesy of the Warburg Institute The Warburg Institute in London is embarking on an ambitious £14.5m development to raise its profile and ward off the stark challenges posed by Brexit. “We have the opportunities— architectural, financial and intellectual—not just to preserve the Warburg as an international beacon for interdisciplinary scholarship but to give it a more public role for the future,” says its director Bill Sherman, the former head of research and collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum. A research institute with 45 master’s and doctoral students, and 3,000 reader’s ticket holders, the Warburg is devoted to the study of cultural memory through the interactions between images and society over time. Its collection of more than 450,000 images and at least 350,000 books is based on the unique library amassed by the German Jewish art historian and banking scion Aby Warburg (1866-1929). Established in his Hamburg home in 1909, it was smuggled out of Nazi Germany to London in 1933. The institute became part of the University of London in 1944, moving into its current building, designed by Charles Holden, in 1957. The Warburg Institute Courtesy of the Warburg Institute The new development by Haworth Tompkins architects, dubbed the Warburg Renaissance, is due to be completed by September 2022. -

Newsletter of the Societas Magica/ No. 4

Newsletter of the Societas Magica/ No. 4 The current issue of the Newsletter is devoted mostly to the activities, collections, and publications of the Warburg Institute in London. Readers desiring further information are urged to communicate with the Institute at the following address, or to access its Website. È Warburg Institute University of London School of Advanced Study Woburn Square, London WC1H 0AB tel. (0171) 580-9663 fax (0171) 436-2852 http://www.sas.ac.uk/warburg/ È The Warburg Institute: History and Current Activities by Will F. Ryan Librarian of the Institute The Warburg Institute is part of the School of Advanced Study in the University of London, but its origins are in pre-World War II Hamburg. Its founder, Aby Warburg (1866-1929),1 was a wealthy historian of Renaissance art and civilization who developed a distinctive interdisciplinary approach to cultural history which included the history of science and religion, psychology, magic and astrology. He was the guiding spirit of a circle of distinguished scholars for whom his library and photographic collection provided a custom- built research center. In 1895 Warburg visited America and studied in particular Pueblo culture, which he regarded as still retaining a consciousness in which magic was a natural element. In his historical study of astrology he was influenced by Franz Boll (part of whose book collection is now in the Warburg library). In 1912 he delivered a now famous lecture on the symbolism of astrological imagery of the frescoes in the Palazzo Schifanoja in Ferrara; he wrote a particularly interesting article on Luther's horoscope; and he began the study of the grimoire called Picatrix, the various versions of which the Warburg Institute is gradually publishing. -

The Warburg Institute and Architectural History 133 CK181 11Vaneck 1Pp Sh.Indd 134 Part Part in Brink, and Claudia

1 2 3 4 5 6 THE WARBURG INSTITUTE 7 8 AND ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 9 10 11 12 13 Caroline van Eck 14 15 16 17 18 At first sight, classical architecture, with its continuous revivals and reworkings 19 of the forms of Greek and Roman building, would seem to offer a privileged field 20 to apply Aby Warburg’s central notion of the survival of antiquity and his view 21 of art history’s unfolding as a process of remembrance, of Mnemosyne. Yet War- 22 burg himself wrote very little on architecture, and after auspicious and impres- 23 sive beginnings by Rudolf Wittkower, Richard Krautheimer, Georg Kubler, and 24 Nikolaus Pevsner, the role of architectural history in the activities of the War- 25 burg Institute, its Library and Journal, dwindled. A brief survey of the Journal of 26 the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes shows that, up to the early 1970s, it published 27 three to four articles on architectural topics every year. Among them are classics 28 in the field that have kept their value to the present day, such as Wittkower’s arti- 29 cles on perspective and Palladianism, Robin Middleton’s article on Cordemoy, 30 or Krautheimer’s on medieval iconography.1 Beginning in the mid- 1970s, archi- 31 32 1. Richard Krautheimer, “Introduction to an ‘Iconogra- tauld Institutes 6 (1943): 154 – 64; George Kubler, “Archi- 33 phy of Mediaeval Architecture’,” Journal of the Warburg tects and Builders in Mexico, 1521 – 1550,” Journal of the and Courtauld Institutes 5 (1942): 1 – 33; Rudolf Wittkower, Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 7 (1944): 7 – 19; Robin 34 “Brunelleschi and Proportion in Perspective,”, Journal Middleton, “The Abbé de Cordemoy and the Graeco- 35 of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 16 (1953): 275 – 91; Gothic Ideal: A Prelude to Romantic Classicism,” Jour 36 Wittkower, “Pseudo- Palladian Elements in English Neo- nal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 25 (1962): Classical Architecture,” Journal of the Warburg and Cour 278 – 320. -

Warburg Renaissance Case Doc LONG Aug 18.Indd

The Warburg Institute: The Future of Cultural Memory Our opportunity For more than a century, the Warburg Institute has transformed the study of art and history. The Warburg was established in Hamburg as the privately funded library of Aby Warburg (1866–1929), the scholarly scion of one of Central Europe’s great banking families. The Institute’s modes of classifi cation and connection anticipated digital thinking, and its methods of gathering and tracing cultural memory were ‘interdisciplinary’ before the word was invented. Its survival is nothing short of a miracle. Thanks to the support of the Warburg family, Samuel Courtauld and others, the Institute was rescued from Nazi Germany in 1933 and became a permanent part of the University of London in 1944. As the only academic institution to fl ee Aby Warburg (far right with outstretched hands) asks Nazi Germany that survives intact in Britain, it remains his four brothers to support the Institute that bears committed to off ering refuge in a time of migration. their name. Hamburg, 21 August 1929. The movement of people and proliferation of images in the twenty-fi rst century has made the diff erent strands of Warburg’s vision and infl uence more powerful than ever—but the transfer of Warburg’s project to London is incomplete. Today, we can apply the Institute’s founding mission, academic strength and revolutionary approach to inform contemporary cultural, political and intellectual work, completing the vision and the building that houses it for new generations. The University of London is investing the core funding needed to repair the Warburg’s landmark building on Woburn Square, and a further £5 million will help us to provide the spaces and functions that have been missing for many decades. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

ANNUAL REPORT 2013-2014 1 The Warburg Institute exists principally to further the study of the classical tradition, that is of those elements of European thought, literature, art and institutions which derive from the ancient world. It houses an Archive, a Library and a Photographic Collection. It is one of the ten member Institutes of the School of Advanced Study of the University of London. The classical tradition is conceived as the theme which unifies the history of Western civilization. The bias is not towards ‘classical’ values in art and literature: students and scholars will find represented all the strands that link medieval and modern civilization with its origins in the ancient cultures of the Near East and the Mediterranean. It is this element of continuity that is stressed in the arrangement of the Library: the tenacity of symbols and images in European art and architecture, the persistence of motifs and forms in Western languages and literatures, the gradual transition, in Western thought, from magical beliefs to religion, science and philosophy, and the survival and transformation of ancient patterns in social customs and political institutions. The Warburg Institute is concerned mainly with cultural history, art history and history of ideas, especially in the Renaissance. It aims to promote and conduct research on the interaction of cultures, using verbal and visual materials. It specializes in the influence of ancient Mediterranean traditions on European culture from the Middle Ages to the modern period. Its open access library has outstanding strengths in Byzantine, Medieval and Renaissance art, Arabic, Medieval and Renaissance philosophy, the history of religion, science and magic, Italian history, the history of the classical tradition, and humanism. -

Warburg Renaissance

Warburg Renaissance Transforming the Warburg Institute warburg.sas.ac.uk/support/warburg-renaissance 1 Warburg’s pioneering work continues to Our Opportunity inspire some of the world’s most influential academics, curators and artists. The Warburg Institute is one of the world’s leading centres for studying the interaction Thanks to the support of the Warburg family, of ideas, images and society. It is dedicated Samuel Courtauld and others, the Institute to the survival and transmission of culture was relocated to London when the Nazis across time and space, with a special rose to power in 1933: it is the only academic institution saved from Nazi Germany to emphasis on the afterlife of antiquity. Its survive intact in Britain. The Warburg Library, Photographic Collection and Archive Institute became a permanent part of the serve as an engine for interdisciplinary University of London in 1944 and is now one research, postgraduate teaching, and an of the nine research institutes that make up active events and publication programme. the University’s School of Advanced Study. The Warburg Institute was established in The Institute houses an open-stack library Hamburg as the privately funded library of of more than 360,000 rare and modern Aby Warburg (1866-1929), the scholarly scion volumes: it is still organised using Warburg’s of one of Europe’s great banking families. original – indeed unique – scheme, with one The Institute’s modes of classification and floor each for Image, Word, Orientation and connection anticipated digital thinking, and Action. Designed for browsing rather than its methods of studying cultural memory searching, and what Warburg called ‘the were ‘interdisciplinary’ before the word law of the good neighbour’, it has a magical was even invented. -

Resources and Techniques for the Study of Renaissance and Early

The Warburg Institute, School of Advanced Study, University of London, Woburn Square, London WC1H 0AB Tel: (020) 7862 8949 Fax: (020) 7862 8910 [email protected] - www.warburg.sas.ac.uk Resources and Techniques for the Study of Renaissance and Early Modern Culture 12 – 15 May 2014 The Warburg Institute at The Warburg Institute Course Overview Course Programme (subject to minor changes) The programme ‘Resources and Techniques for the Study of Renaissance Monday, 12 May and Early Modern Culture’ provides specialist research training to doctoral 10.00 Registration students working on Renaissance and Early Modern subjects in a range 10.30 Paul Taylor: Method in Iconography 11.30 Coffee of disciplines at universities across the UK and the rest of the world. The 12.00 Paul Taylor: Method in Iconology programme draws on the combined skills in electronic resources, archival 1.00 Lunch break sources, manuscripts, books, and images of the staff of the Warburg Institute 2.00 Ian Jones, François Quiviger, Sarah Richardson: and the University of Warwick. These are two of the major centres in Britain The Digital Renaissance I 3.00 Ian Jones, Francois Quiviger, Sarah Richardson: for the study of the Renaissance and the Early Modern period. The Digital Renaissance II 4.00 Tea The programme consists of a series of strands held over four days from 4.30 François Quiviger: Library registration for course participants Monday 12 to Thursday 15 May 2014 at the Warburg Institute in London. The programme is taught by staff from the Warburg Institute and the Tuesday, 13 May 10.30 Rembrandt Duits: Renaissance astronomy/astrology University of Warwick. -

Cohort Development: English Language & Literature (Including Other Related Areas)

King’s College London :: School of Advanced Study :: University College London Cohort Development: English Language & Literature (including other related areas) Activity Type Run By Time Contact Seminar Institute of English Studies, Throughout Book Collecting [email protected] Open to All University of London the year Seminar Institute of English Studies, Throughout Contemporary Fiction Research [email protected] Open to All University of London the year Contemporary Innovative Seminar Institute of English Studies, Throughout [email protected] Poetry Research Open to All University of London the year Seminar Institute of English Studies, Throughout Djuna Barnes Research [email protected] Open to All University of London the year Ezra Pound Cantos Reading Seminar Institute of English Studies, Throughout [email protected] Group Open to All University of London the year Seminar Institute of English Studies, Throughout History of Libraries Research [email protected] Open to All University of London the year Seminar Institute of English Studies, Throughout IES Research Fellows' [email protected] Open to All University of London the year Seminar Institute of English Studies, Throughout Irish Studies [email protected] Open to All University of London the year Seminar Institute of English Studies, Throughout Literary and Critical Theory [email protected] Open to All University of London the year Seminar Institute of English Studies, Throughout Literary London Reading Group [email protected] Open to All University of London the year London Forum for Authorship Seminar Institute of English -

![E. H. Gombrich, the Warburg Institute: a Personal Memoire, the Art Newspaper, 2 November, 1990, Pp.9 [Trapp No.1990P.1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6508/e-h-gombrich-the-warburg-institute-a-personal-memoire-the-art-newspaper-2-november-1990-pp-9-trapp-no-1990p-1-2506508.webp)

E. H. Gombrich, the Warburg Institute: a Personal Memoire, the Art Newspaper, 2 November, 1990, Pp.9 [Trapp No.1990P.1]

E. H. Gombrich, The Warburg Institute: A Personal Memoire, The Art Newspaper, 2 November, 1990, pp.9 [Trapp no.1990P.1] In 1933 Nazism drove a band of original and profound scholars, then a great library, to settle in Britain. Out of these elements grew the world famous Institute, whose approach to the thinking of the past has incomparably enriched the understanding of art. Will the 1990s see this living intellectual force stifled by British government meanness and philistinism? LONDON. The Warburg Institute grew out of and around one man's own library, and although it is now larger by tens of thousands of volumes, it has retained the feeling of a private library , with open stacks, and the books arranged by topic in a way that invites the reader to start browsing in the subject next to his own. The Institute is world famous as a centre for cross-disciplinary cultural and intellectual history and its library is both its essence and its basis. That is why the financial crisis in scholarly libraries, which has affected European, and especially British, places of learning over the last decade, is a particularly dangerous threat to the Warburg, which depends for its funding on the University of London. One statistic will do: between 1981 and 1986 in the UK, library expenditure as a proportion of university expenditure fell by 9%, but the prices of books, periodicals and binding rose by 79%. Help is urgently required if the Warburg's library, and life, are not to shrivel. Its only hope is a generous response to the appeal which it has launched. -

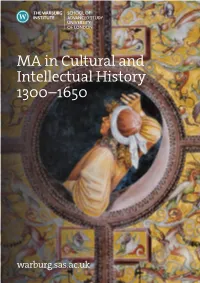

MA in Cultural and Intellectual History 1300–1650

MA in Cultural and Intellectual History 1300–1650 warburg.sas.ac.uk About the degree The Warburg Institute MA in Cultural and Intellectual History aims to equip students for interdisciplinary research in the late medieval and early modern period, with a particular emphasis on the reception of the classical tradition. Students will become part of an international community of scholars, working in a world-famous library. They will broaden their range of knowledge to include the historically informed interpretation of images and texts, art history, philosophy, history of science, literature and the impact of religion on society. During this twelve-month, full-time course, students will improve their knowledge of Latin, French and Italian and will acquire the library and archival skills essential for research on primary texts. Although it is a qualification in its own right, the MA is also designed to provide training for further research at doctoral level. It is taught through classes and supervision by members of the academic staff of the Institute and by outside teachers. The teaching staff are leading academics in their field who have published widely. Research strengths include: changes in philosophical trends between the Middle Ages and the Enlightenment; early modern material culture; and forms of religious non-conformism in sixteenth- and seventeenth- century Europe. For further details on the research interests of teaching staff see the module table in this leaflet or visit warburg.sas.ac.uk/about/people/teaching-staff “I came to study at the Warburg with a modicum of trepidation, due to the overwhelming reputation that precedes and surrounds the Institute. -

Institute of Classical Studies

SAS ANNUAL REPORT 1997-1998 PREFACE I am delighted to be able to present the fourth annual report of the School. Such a report can give only a brief and rather austere overview of a year of varied and intensive scholarly activity in all the subjects and disciplines covered by its Institutes and Programmes, but I hope that it may encourage readers not already familiar with the School to inquire further about things that have interested them. Institutes will welcome such inquiries, and a lively set of web pages is accessible via http://www.sas.ac.uk. In the course of the year the School developed in a new and exciting direction as a result of the decision of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine to become an Associate of the School. The aim is to strengthen and multiply the informal links which have long existed between that Institute and various parts of the School, for the reciprocal enrichment of our academic programmes and the enhancement of research opportunities for users of the School's, and the Institute's, remarkable libraries. The collections have great complementary strengths. Moving among them should be easy, not just because of their physical proximity but also because they will, in future, use the same type of automated catalogue system. The co-operation agreement concluded last year with the Ecole Nationale des Chartes in Paris, and the arrival of the Wellcome Institute as an Associate, demonstrate the School's capacity to offer free passage to scholars across an ever-expanding landscape of humanities and social science research resources, without regard for national and institutional barriers. -

MA in Art History, Curatorship And

MA in Art History, Curatorship and Renaissance Culture warburg.sas.ac.uk The course was always inspiring and Investing in your future assiduously well taught, whether we were learning about picture Many Warburg alumni have gone on to framing and restoration, studying pursue PhD study at the Institute and Michelangelo’s letters in his own elsewhere across the globe, including the handwriting, or handling rare books Universities of Cambridge, Copenhagen, from the world-class library. Notre Dame (US), Padua, and La Sapienza “David Daly, 2016 (Rome), and to pursue careers at cultural institutions such as Sotheby’s, the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford), the Why study with” us? Government Art Collection, the National Gallery, Art Council England, and the As a student at the Warburg Institute, you National Library, Argentina. Read more will have access to the best resources for about Warburg alumni: the study of Renaissance art and culture in warburg.blogs.sas.ac.uk London. Unparalleled staff contact hours are combined with access to the Warburg Library, with its unique cataloguing system specifically designed to aid research, This 12-month full-time or 36-month part- and the National Gallery’s collection and time programme provides mastery in: archives. About the The intellectual discipline of Art History Through the Institute’s research projects, for academic research and museum degree work, focusing primarily on the period fellowship programmes and events, 1300–1700, its objects of study, and and its informal collegiate atmosphere, modes of interpretation students have extensive opportunities The MA in Art History, for networking with an international The intellectual and practical aspects community of scholars, which significantly Curatorship and Renaissance of curatorship, with the opportunity to enriches the learning experience and can Culture aims to train a new curate an online exhibition as part of generation of art historians degree coursework provide ideal connections for your future career.