OCR Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William & Mary Football Record Book

William & Mary CONTENTS & QUICK FACTS Football Record Book as of June 1, 2020 CONTENTS Contents . 1 Tribe in the Pros . 2-3 Honors & Awards . 6-9 Records . 10-11 Individual Single-Season Records . 12-13 Individual Career Records . 14 All-Time Top Performances . 15 Team Game Records . 16 Team Season Records . 17 The Last Time … . 18-22 All-Time Coaches & Captains . 23-24 All-Time Series Results . 25-26 All-Time Results . 27-33 All-Time Assistant Coaches . 34 All-Time Roster . 35-46 WWW.TRIBEATHLETICS.COM 1 TRIBE IN THE PROS B.W. Webb Luke Rhodes DeAndre Houston-Carson Cincinnati Bengals Indianapolis Colts Chicago Bears Name Pro Team Years Dave Corley, Jr . Hamilton Tiger-Cats 2003-04 R .J . Archer Minnesota 2010 Calgary Stampeders 2006 Milwaukee Mustangs 2011 Jerome Couplin III Detroit Lions 2014 Georgia Force 2012 Buffalo Bills 2014 Detroit Lions 2012 Philadelphia Eagles 2014-15 Jacksonville Sharks 2013-14 Los Angeles Rams 2016 Seattle Seahawks 2015 Hamilton Tiger-Cats 2018 Drew Atchison Dallas Cowboys 2008 Orlando Apollos 2019 Bill Bowman Detroit Lions 1954, 1956 Los Angeles Wildcats 2020 Pittsburgh Steelers 1957 Derek Cox Jacksonville Jaguars 2009-12 Tom Brown Pittsburgh Steelers 1942 San Diego Chargers 2013 Russ Brown Honolulu Hawaiians 1974 Minnesota Vikings 2014 New York Giants 1974 Baltimore Ravens 2014 Washington Redskins 1975 New England Patriots 2015 Todd Bushnell Baltimore Colts 1973 Lou Creekmur Detroit Lions 1950-59 David Caldwell Indianapolis Colts 2010-11 Dan Darragh Buffalo Bills 1968-70 New York Giants 2013 DeVonte Dedmon -

Eagles' Team Travel

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2019-2020 EDITIOn PHILADELPHIA EAGLES Team History The Eagles have been a Philadelphia institution since their beginning in 1933 when a syndicate headed by the late Bert Bell and Lud Wray purchased the former Frankford Yellowjackets franchise for $2,500. In 1941, a unique swap took place between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh that saw the clubs trade home cities with Alexis Thompson becoming the Eagles owner. In 1943, the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh franchises combined for one season due to the manpower shortage created by World War II. The team was called both Phil-Pitt and the Steagles. Greasy Neale of the Eagles and Walt Kiesling of the Steelers were co-coaches and the team finished 5-4-1. Counting the 1943 season, Neale coached the Eagles for 10 seasons and he led them to their first significant successes in the NFL. Paced by such future Pro Football Hall of Fame members as running back Steve Van Buren, center-linebacker Alex Wojciechowicz, end Pete Pihos and beginning in 1949, center-linebacker Chuck Bednarik, the Eagles dominated the league for six seasons. They finished second in the NFL Eastern division in 1944, 1945 and 1946, won the division title in 1947 and then scored successive shutout victories in the 1948 and 1949 championship games. A rash of injuries ended Philadelphia’s era of domination and, by 1958, the Eagles had fallen to last place in their division. That year, however, saw the start of a rebuilding program by a new coach, Buck Shaw, and the addition of quarterback Norm Van Brocklin in a trade with the Los Angeles Rams. -

Monday Night Notes for Use As Desired for Additional Information, Nfl-80 10/6/05 Contact: Steve Alic (212 450 2066)

NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE 280 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017 (212) 450-2000 * FAX (212) 681-7573 WWW.NFLMedia.com Joe Browne, Executive Vice President-Communications Greg Aiello, Vice President-Public Relations MONDAY NIGHT NOTES FOR USE AS DESIRED FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION, NFL-80 10/6/05 CONTACT: STEVE ALIC (212 450 2066) STEEL MEETS SURF IN MNF SHOWDOWN OF AFC POWERS For generations, countless experiments in grade school science labs have proven that electricity flows through steel. Before a national television audience on ABC Monday night, America will learn if the San Diego Chargers’ offense – outfitted in its classic 1960s uniform – can move through the Pittsburgh Steelers in a matchup of 2004 division champions. San Diego (2-2) has won back-to-back games in impressive fashion. In the past two weeks, running back LA DAINIAN TOMLINSON has darted for 326 yards and five touchdowns while throwing a TD pass and adding 62 receiving yards for good measure. Quarterback DREW BREES has completed a whopping 38 of 46 passes (82.6 percent) with four touchdowns and no interceptions in those two wins. Pittsburgh (2-1), rested after a bye week, counters with a pass rush averaging one sack every 7.7 pass plays – best in the NFL. A defensive front seven with four All-Stars will challenge the hot Chargers. Offensively, despite his last name, running back WILLIE PARKER is anything but stationary, standing fifth in the AFC with 327 yards despite the bye. And oh, by the way, quarterback BEN ROETHLISBERGER wears a shiny 131.8 passer rating – the league’s highest. -

Mcafee Takes a Handoff from Sid Luckman (1947)

by Jim Ridgeway George McAfee takes a handoff from Sid Luckman (1947). Ironton, a small city in Southern Ohio, is known throughout the state for its high school football program. Coach Bob Lutz, head coach at Ironton High School since 1972, has won more football games than any coach in Ohio high school history. Ironton High School has been a regular in the state football playoffs since the tournament’s inception in 1972, with the school winning state titles in 1979 and 1989. Long before the hiring of Bob Lutz and the outstanding title teams of 1979 and 1989, Ironton High School fielded what might have been the greatest gridiron squad in school history. This nearly-forgotten Tiger squad was coached by a man who would become an assistant coach with the Cleveland Browns, general manager of the Buffalo Bills and the second director of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The squad featured three brothers, two of which would become NFL players, in its starting eleven. One of the brothers would earn All-Ohio, All-American and All-Pro honors before his enshrinement in Canton, Ohio. This story is a tribute to the greatest player in Ironton High School football history, his family, his high school coach and the 1935 Ironton High School gridiron squad. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the undefeated and untied Ironton High School football team featuring three players with the last name of McAfee. It was Ironton High School’s first perfect football season, and the school would not see another such gridiron season until 1978. -

“Notes & Nuggets” from the Pro

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 09/20/2019 WEEKLY “NOTES & NUGGETS” FROM THE PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME BRONZED BUSTS TRAVEL TO EAGLES FANTENNIAL; BILLY SHAW TOOK PART IN THE HEART OF A HALL OF FAMER PROGRAM; PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME RING OF EXCELLENCE CEREMONIES; MUSEUM DAY; FROM THE ARCHIVES: HALL OF FAMERS ENSHRINED IN THE SAME YEAR FROM THE SAME COLLEGE CANTON, OHIO – The following is a sampling of events, happenings and notes that highlight how the Pro Football Hall of Fame serves its important mission to “Honor the Heroes of the Game, Preserve its History, Promote its Values & Celebrate Excellence EVERYWHERE!” 14 BRONZED BUSTS TRAVEL TO PHILADELPHIA FOR EAGLES FANTENNIAL The Pro Football Hall of Fame sent the Bronzed Busts of 14 Eagles Legends to Philadelphia for the Eagles Fantennial Festival taking place as part of the National Football League’s 100th Season. The busts will be on display during “Eagles Fantennial Festival – Birds. Bites. Beer.” at the Cherry Street Pier on Saturday, Sept. 21 and at Lincoln Financial Field prior to the Eagles game agains the Detroit Lions on Sunday, Sept. 22. The Bronzed Busts to be displayed include: • Bert Bell • Sonny Jurgensen • Norm Van Brocklin • Chuck Bednarik • Tommy McDonald • Steve Van Buren • Bob Brown • Earl “Greasy” Neale • Reggie White • Brian Dawkins • Pete Pihos • Alex Wojciechowicz • Bill Hewitt • Jim Ringo More information on the Eagles Fantennial can be found at https://fanpages.philadelphiaeagles.com/nfl100.html. September 16-19, 2020 A once-in-every- other-lifetime celebration to kick off the NFL’s next century in the city where the league was born. -

Vol. 10, No. 2 (1988) JACK FERRANTE: EAGLES GREAT

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 10, No. 2 (1988) JACK FERRANTE: EAGLES GREAT By Richard Pagano Reprinted from Town Talk, 1/6/88 In 1933, Bert Bell and Lud Wray formed a syndicate to purchase the Frankford Yellowjackets' N.F.L. franchise. On July 9 they bought the team for $2,500. Bell named the team "The Eagles", in honor of the eagle, which was the symbol of the National Recovery Administration of the New Deal. The Eagles' first coach was Wray and Bell became Philadelphia's first general managers. In 1936, Bert Bell purchased sole ownership of the team for $4,000. He also disposed of Wray as head coach, and took on the job himself. From 1933 until 1941, the Philadelphia Eagles never had a winning season. Even Davey O'Brien, the All-American quarterback signed in 1939, could not the Eagles out of the Eastern Division cellar. Bert Bell finally sold the Eagles in 1941. He sold half the franchise to Alexis Thompson of New York. Before the season, Rooney and Bell swapped Thompson their Philadelphia franchise for his Pittsburgh franchise. The new owner hired Earle "Greasy" Neale to coach the team. In 1944, the Eagles really started winning. They finished with a record of 7-1-2 and ended the season in second place in the Eastern Division. From 1944 until 1950, the Philadelphia Eagles enjoyed their most successful years in the history of the franchise. They finished second in the Eastern Division three times and also won the Eastern Division championship three times. The Eagles played in three consecutive N.F.L. -

Eagles Hall of Fame

EAGLES HALL OF FAME DAVID AKERS BERT BELL KICKER OWNER Eagles Career: 1999-2010 Eagles Career: 1933-40 Eagles Hall of Fame Inductee: 2017 Eagles Hall of Fame Inductee: 1987 Pro Football Hall of Fame Inductee: 1963 Recognized as the greatest kicker in franchise history, Akers earned five As the first owner of the Eagles (1933-40), co-owner of the Steelers Pro Bowl nods as an Eagle and established regular-season and postsea- (1941-46), and NFL commissioner (1946-59), Bell instituted the college son team records in points (1,323; 134) and field goals made (294; 31). draft and implemented TV policies, including the home game blackouts. During his time in Philadelphia, Akers ranked 2nd in the NFL in points In 1933, he moved the Frankford Yellowjackets to Philadelphia and re- and field goals made. His recognition as one of the league’s best kickers named them the Eagles. In 1946, he moved the NFL office from Chicago earned him a spot on the NFL’s All-Decade Team of the 2000s. to Bala Cynwyd, PA. Bell played and coached at Pennsylvania and led the Quakers to the Rose Bowl in 1916. A founder of the Maxwell Football Club, Bell was born February 25, 1895, in Philadelphia. ERIC ALLEN CORNERBACK BILL BERGEY Eagles Career: 1988-94 MIDDLE LINEBACKER Eagles Hall of Fame Inductee: 2011 Eagles Career: 1974-80 Eagles Hall of Fame Inductee: 1988 A second-round draft choice of the Eagles in 1988, Allen played seven seasons in Philadelphia, earning five Pro Bowl and three All-Pro selec- tions. -

All-Time All-America Teams

1944 2020 Special thanks to the nation’s Sports Information Directors and the College Football Hall of Fame The All-Time Team • Compiled by Ted Gangi and Josh Yonis FIRST TEAM (11) E 55 Jack Dugger Ohio State 6-3 210 Sr. Canton, Ohio 1944 E 86 Paul Walker Yale 6-3 208 Jr. Oak Park, Ill. T 71 John Ferraro USC 6-4 240 So. Maywood, Calif. HOF T 75 Don Whitmire Navy 5-11 215 Jr. Decatur, Ala. HOF G 96 Bill Hackett Ohio State 5-10 191 Jr. London, Ohio G 63 Joe Stanowicz Army 6-1 215 Sr. Hackettstown, N.J. C 54 Jack Tavener Indiana 6-0 200 Sr. Granville, Ohio HOF B 35 Doc Blanchard Army 6-0 205 So. Bishopville, S.C. HOF B 41 Glenn Davis Army 5-9 170 So. Claremont, Calif. HOF B 55 Bob Fenimore Oklahoma A&M 6-2 188 So. Woodward, Okla. HOF B 22 Les Horvath Ohio State 5-10 167 Sr. Parma, Ohio HOF SECOND TEAM (11) E 74 Frank Bauman Purdue 6-3 209 Sr. Harvey, Ill. E 27 Phil Tinsley Georgia Tech 6-1 198 Sr. Bessemer, Ala. T 77 Milan Lazetich Michigan 6-1 200 So. Anaconda, Mont. T 99 Bill Willis Ohio State 6-2 199 Sr. Columbus, Ohio HOF G 75 Ben Chase Navy 6-1 195 Jr. San Diego, Calif. G 56 Ralph Serpico Illinois 5-7 215 So. Melrose Park, Ill. C 12 Tex Warrington Auburn 6-2 210 Jr. Dover, Del. B 23 Frank Broyles Georgia Tech 6-1 185 Jr. -

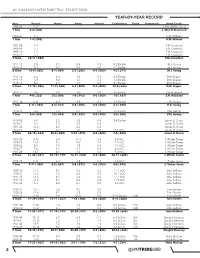

@Wmtribembb 2 Year-By-Year Record

WILLIAM & MARY MEN’S BASKETBALL RECORD BOOK YEAR-BY-YEAR RECORD Year Record Home Away Neutral Conference Finish Postseason Head Coach 1905-06 3-2 J. Merrill Blanchard 1 Year 3-2 (.600) J. Merrill Blanchard 1906-07 1-4 H.W. Withers 1 Year 1-4 (.200) H.W. Withers 1907-08 1-4 F.M. Crawford 1908-09 7-3 F.M. Crawford 1909-10 1-3 F.M. Crawford 1910-11 3-1 F.M. Crawford 4 Years 12-11 (.522) F.M. Crawford 1911-12 2-5 2-1 0-4 0-0 0-2 EVIAA W.J. Young 1912-13 8-1 6-0 2-1 0-0 4-1 EVIAA W.J. Young 2 Years 10-6 (.625) 8-1 (.889) 2-5 (.286) 0-0 (.000) 4-3 (.571) W.J. Young 1913-14 4-6 3-4 1-2 0-0 2-4 EVIAA D.W. Draper 1914-15 5-8 4-2 1-6 0-0 3-3 EVIAA D.W. Draper 1915-16 8-4 4-3 4-1 0-0 5-1 EVIAA D.W. Draper 3 Years 17-18 (.486) 11-9 (.550) 6-9 (.400) 0-0 (.000) 10-8 (.556) D.W. Draper 1916-17 4-8 3-2 1-6 0-0 1-5 EVIAA S.H. Hubbard 1 Year 4-8 (.333) 3-2 (.600) 1-6 (.143) 0-0 (.000) 1-5 (.167) S.H. Hubbard 1917-18 6-11 4-3 2-8 0-0 3-3 EVIAA H.K. Young 1 Year 6-11 (.353) 4-3 (.571) 2-8 (.200) 0-0 (.000) 3-3 (.500) H.K. -

Bert Milling

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 24, No. 2 (2002) “This Young Kid from Down South”: Bert Milling by Mel Bashore Although he now refers to himself as “an old codger,” We did not find out until we reached Richmond that the when Bert Milling played for the University of Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. Richmond he was credited with being one of the His memory of the Arrows final game of the season youngest team captains in the country when he was against the Kenosha Cardinals in Memphis, nineteen years old. Prior to college, he attended a Tennessee, is vivid: small prep school in Mobile, Alabama. At University Military School (UMS) they only had thirteen players on We picked up a Tennessee team on the way over composed the squad. The heaviest player on the team topped the of George Cafego as the quarterback, Bob Suffridge and scales at 150 pounds. The team was nicknamed the Molinski as guards and others I can’t recall. I do recall the "Flea Circus" because of the diminutive size of its Cardinals had Ki Aldrich as their center and I was amazed players. Milling played guard and in the two years that and fascinated with the ease with which Suffridge handled he played under coach Andy Eddington, they amassed him. A forearm shiver and Bob was in the Cardinals’ backfield a record of 20-2. Milling ascribed their winning record on his back side. The game plan was for the Arrows to play to an offensive medley of “spinner hand-offs, downfield one quarter and the Tenn. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A. -

Kit Young's Sale #154

Page 1 KIT YOUNG’S SALE #154 AUTOGRAPHED BASEBALLS 500 Home Run Club 3000 Hit Club 300 Win Club Autographed Baseball Autographed Baseball Autographed Baseball (16 signatures) (18 signatures) (11 signatures) Rare ball includes Mickey Mantle, Ted Great names! Includes Willie Mays, Stan Musial, Eddie Murray, Craig Biggio, Scarce Ball. Includes Roger Clemens, Williams, Barry Bonds, Willie McCovey, Randy Johnson, Early Wynn, Nolan Ryan, Frank Robinson, Mike Schmidt, Jim Hank Aaron, Rod Carew, Paul Molitor, Rickey Henderson, Carl Yastrzemski, Steve Carlton, Gaylord Perry, Phil Niekro, Thome, Hank Aaron, Reggie Jackson, Warren Spahn, Tom Seaver, Don Sutton Eddie Murray, Frank Thomas, Rafael Wade Boggs, Tony Gwynn, Robin Yount, Pete Rose, Lou Brock, Dave Winfield, and Greg Maddux. Letter of authenticity Palmeiro, Harmon Killebrew, Ernie Banks, from JSA. Nice Condition $895.00 Willie Mays and Eddie Mathews. Letter of Cal Ripken, Al Kaline and George Brett. authenticity from JSA. EX-MT $1895.00 Letter of authenticity from JSA. EX-MT $1495.00 Other Autographed Baseballs (All balls grade EX-MT/NR-MT) Authentication company shown. 1. Johnny Bench (PSA/DNA) .........................................$99.00 2. Steve Garvey (PSA/DNA) ............................................ 59.95 3. Ben Grieve (Tristar) ..................................................... 21.95 4. Ken Griffey Jr. (Pro Sportsworld) ..............................299.95 5. Bill Madlock (Tristar) .................................................... 34.95 6. Mickey Mantle (Scoreboard, Inc.) ..............................695.00 7. Don Mattingly (PSA/DNA) ...........................................99.00 8. Willie Mays (PSA/DNA) .............................................295.00 9. Pete Rose (PSA/DNA) .................................................99.00 10. Nolan Ryan (Mill Creek Sports) ............................... 199.00 Other Autographed Baseballs (Sold as-is w/no authentication) All Time MLB Records Club 3000 Strike Out Club 11.