Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Metallomics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

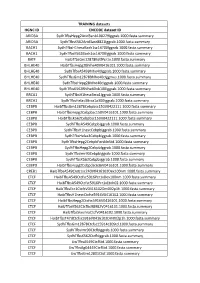

TRAINING Datasets HGNC ID ENCODE Dataset ID ARID3A

TRAINING datasets HGNC ID ENCODE dataset ID ARID3A SydhT+sHepg2Arid3anb100279Iggrab.1000.fasta.summary ARID3A SydhT+sK562Arid3asC8821Iggrab.1000.fasta.summary BACH1 SydhT+sH1hesCBaCh1sC14700Iggrab.1000.fasta.summary BACH1 SydhT+sK562BaCh1sC14700Iggrab.1000.fasta.summary BATF HaibT+sGm12878BaJPCr1x.1000.fasta.summary BHLHE40 HaibT+sHepg2Bhlhe40V0416101.1000.fasta.summary BHLHE40 SydhT+sA549Bhlhe40Iggrab.1000.fasta.summary BHLHE40 SydhT+sGm12878Bhlhe40CIggmus.1000.fasta.summary BHLHE40 SydhT+sHepg2Bhlhe40CIggrab.1000.fasta.summary BHLHE40 SydhT+sK562Bhlhe40nb100Iggrab.1000.fasta.summary BRCA1 SydhT+sH1hesCBrCa1Iggrab.1000.fasta.summary BRCA1 SydhT+sHelas3BrCa1a300Iggrab.1000.fasta.summary CEBPB HaibT+sGm12878CebpbsC150V0422111.1000.fasta.summary CEBPB HaibT+sHepg2CebpbsC150V0416101.1000.fasta.summary CEBPB HaibT+sK562CebpbsC150V0422111.1000.fasta.summary CEBPB SydhT+sA549CebpbIggrab.1000.fasta.summary CEBPB SydhT+sH1hesCCebpbIggrab.1000.fasta.summary CEBPB SydhT+sHelas3CebpbIggrab.1000.fasta.summary CEBPB SydhT+sHepg2CebpbForsklnStd.1000.fasta.summary CEBPB SydhT+sHepg2CebpbIggrab.1000.fasta.summary CEBPB SydhT+sImr90CebpbIggrab.1000.fasta.summary CEBPB SydhT+sK562CebpbIggrab.1000.fasta.summary CEBPD HaibT+sHepg2CebpdsC636V0416101.1000.fasta.summary CREB1 HaibT+sA549Creb1sC240V0416102Dex100nm.1000.fasta.summary CTCF HaibT+sA549CtCfsC5916PCr1xDex100nm.1000.fasta.summary CTCF HaibT+sA549CtCfsC5916PCr1xEtoh02.1000.fasta.summary CTCF HaibT+sECC1CtCfCV0416102Dm002p1h.1000.fasta.summary CTCF HaibT+sH1hesCCtCfsC5916V0416102.1000.fasta.summary -

Activation of the STAT3 Signaling Pathway by the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Protein of Arenavirus

viruses Article Activation of the STAT3 Signaling Pathway by the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Protein of Arenavirus Qingxing Wang 1,2 , Qilin Xin 3 , Weijuan Shang 1, Weiwei Wan 1,2, Gengfu Xiao 1,2,* and Lei-Ke Zhang 1,2,* 1 State Key Laboratory of Virology, Wuhan Institute of Virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430071, hubei, China; [email protected] (Q.W.); [email protected] (W.S.); [email protected] (W.W.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 UMR754, Viral Infections and Comparative Pathology, 50 Avenue Tony Garnier, CEDEX 07, 69366 Lyon, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (G.X.); [email protected] (L.-K.Z.) Abstract: Arenaviruses cause chronic and asymptomatic infections in their natural host, rodents, and several arenaviruses cause severe hemorrhagic fever that has a high mortality in infected humans, seriously threatening public health. There are currently no FDA-licensed drugs available against arenaviruses; therefore, it is important to develop novel antiviral strategies to combat them, which would be facilitated by a detailed understanding of the interactions between the viruses and their hosts. To this end, we performed a transcriptomic analysis on cells infected with arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), a neglected human pathogen with clinical significance, and found that the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling pathway was activated. A further investigation indicated that STAT3 could be activated by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase L protein (Lp) of LCMV. Our functional analysis found that STAT3 cannot affect Citation: Wang, Q.; Xin, Q.; Shang, LCMV multiplication in A549 cells. -

In Vivo Studies Using the Classical Mouse Diversity Panel

The Mouse Diversity Panel Predicts Clinical Drug Toxicity Risk Where Classical Models Fail Alison Harrill, Ph.D The Hamner-UNC Institute for Drug Safety Sciences 0 The Importance of Predicting Clinical Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR) Figure: Cath O’Driscoll Nature Publishing 2004 Risk ID PGx Testing 1 People Respond Differently to Drugs Pharmacogenetic Markers Identified by Genome-Wide Association Drug Adverse Drug Risk Allele Reaction (ADR) Abacavir Hypersensitivity HLA-B*5701 Flucloxacillin Hepatotoxicity Allopurinol Cutaneous ADR HLA-B*5801 Carbamazepine Stevens-Johnson HLA-B*1502 Syndrome Augmentin Hepatotoxicity DRB1*1501 Ximelagatran Hepatotoxicity DRB1*0701 Ticlopidine Hepatotoxicity HLA-A*3303 Average preclinical populations and human hepatocytes lack the diversity to detect incidence of adverse events that occur only in 1/10,000 people. Current Rodent Models of Risk Assessment The Challenge “At a time of extraordinary scientific progress, methods have hardly changed in several decades ([FDA] 2004)… Toxicologists face a major challenge in the twenty-first century. They need to embrace the new “omics” techniques and ensure that they are using the most appropriate animals if their discipline is to become a more effective tool in drug development.” -Dr. Michael Festing Quantitative geneticist Toxicol Pathol. 2010;38(5):681-90 Rodent Models as a Strategy for Hazard Characterization and Pharmacogenetics Genetically defined rodent models may provide ability to: 1. Improve preclinical prediction of drugs that carry a human safety risk 2. -

TFEB Regulates Murine Liver Cell Fate During Development and Regeneration ✉ Nunzia Pastore 1,2 , Tuong Huynh1,2, Niculin J

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16300-x OPEN TFEB regulates murine liver cell fate during development and regeneration ✉ Nunzia Pastore 1,2 , Tuong Huynh1,2, Niculin J. Herz1,2, Alessia Calcagni’ 1,2, Tiemo J. Klisch1,2, Lorenzo Brunetti 3,4, Kangho Ho Kim5, Marco De Giorgi6, Ayrea Hurley6, Annamaria Carissimo7, Margherita Mutarelli7, Niya Aleksieva 8, Luca D’Orsi7, William R. Lagor6, David D. Moore 5, ✉ Carmine Settembre7,9, Milton J. Finegold10, Stuart J. Forbes8 & Andrea Ballabio 1,2,7,9 1234567890():,; It is well established that pluripotent stem cells in fetal and postnatal liver (LPCs) can differentiate into both hepatocytes and cholangiocytes. However, the signaling pathways implicated in the differentiation of LPCs are still incompletely understood. Transcription Factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy, is known to be involved in osteoblast and myeloid differentiation, but its role in lineage commitment in the liver has not been investigated. Here we show that during development and upon regen- eration TFEB drives the differentiation status of murine LPCs into the progenitor/cho- langiocyte lineage while inhibiting hepatocyte differentiation. Genetic interaction studies show that Sox9, a marker of precursor and biliary cells, is a direct transcriptional target of TFEB and a primary mediator of its effects on liver cell fate. In summary, our findings identify an unexplored pathway that controls liver cell lineage commitment and whose dysregulation may play a role in biliary cancer. 1 Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute, Texas Children Hospital, Houston, TX 77030, USA. 2 Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA. -

Interferon Regulatory Factor 3-CL, an Isoform of IRF3, Antagonizes Activity of IRF3

Cellular & Molecular Immunology (2011) 8, 67–74 ß 2011 CSI and USTC. All rights reserved 1672-7681/11 $32.00 www.nature.com/cmi RESEARCH ARTICLE Interferon regulatory factor 3-CL, an isoform of IRF3, antagonizes activity of IRF3 Chunhua Li1,2,3, Lixin Ma2 and Xinwen Chen1 Interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), one member of the IRF family, plays a central role in induction of type I interferon (IFN) and regulation of apoptosis. Controlled activity of IRF3 is essential for its functions. During reverse transcription (RT)-PCR to clone the full-length open reading frame (ORF) of IRF3, we cloned a full-length ORF encoding an isoform of IRF3, termed as IRF3-CL, and has a unique carboxyl-terminus of 125 amino acids. IRF3-CL is ubiquitously expressed in distinct cell lines. Overexpression of IRF3-CL inhibits Sendai virus (SeV)-triggered induction of IFN-b and SeV-induced and inhibitor of NF-kB kinase-e (IKKe)-mediated nuclear translocation of IRF3. When IKKe is overexpressed, IRF3-CL is associated with IRF3. These results suggest that IRF3-CL, the alternative splicing isoform of IRF-3, may function as a negative regulator of IRF3. Cellular & Molecular Immunology (2011) 8, 67–74; doi:10.1038/cmi.2010.55; published online 6 December 2010 Keywords: interferon regulatory factor 3; negative regulation; splicing variant INTRODUCTION A single gene is capable of generating multiple transcripts from a The interferon regulatory factor (IRF) family of transcriptional factors common mRNA precursor through alternative splicing, which may plays versatile roles in many biological processes, including innate and produce distinct protein isoforms with diverse and even antagonistic adaptive immune responses, cell growth control, apoptosis and functions. -

Comprehensive Study of Nuclear Receptor DNA Binding Provides a Revised Framework for Understanding Receptor Specificity

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10264-3 OPEN Comprehensive study of nuclear receptor DNA binding provides a revised framework for understanding receptor specificity Ashley Penvose 1,2,4, Jessica L. Keenan 2,3,4, David Bray2,3, Vijendra Ramlall 1,2 & Trevor Siggers 1,2,3 The type II nuclear receptors (NRs) function as heterodimeric transcription factors with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) to regulate diverse biological processes in response to endogenous 1234567890():,; ligands and therapeutic drugs. DNA-binding specificity has been proposed as a primary mechanism for NR gene regulatory specificity. Here we use protein-binding microarrays (PBMs) to comprehensively analyze the DNA binding of 12 NR:RXRα dimers. We find more promiscuous NR-DNA binding than has been reported, challenging the view that NR binding specificity is defined by half-site spacing. We show that NRs bind DNA using two distinct modes, explaining widespread NR binding to half-sites in vivo. Finally, we show that the current models of NR specificity better reflect binding-site activity rather than binding-site affinity. Our rich dataset and revised NR binding models provide a framework for under- standing NR regulatory specificity and will facilitate more accurate analyses of genomic datasets. 1 Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA. 2 Biological Design Center, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA. 3 Bioinformatics Program, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA. 4These authors contributed equally: Ashley Penvose, Jessica L. Keenan. Correspondence -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

IRF5 Gene Interferon Regulatory Factor 5

IRF5 gene interferon regulatory factor 5 Normal Function The protein produced from the IRF5 gene, called interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5), acts as a transcription factor, which means that it attaches (binds) to specific regions of DNA and helps control the activity of certain genes. When a virus is recognized in the cell, the IRF5 gene is turned on (activated), which leads to the production of IRF5 protein. The protein binds to specific regions of DNA that regulate the activity of genes that produce interferons and other cytokines. Cytokines are proteins that help fight infection by promoting inflammation and regulating the activity of immune system cells. In particular, interferons control the activity of genes that help block the replication of viruses, and they stimulate the activity of certain immune system cells known as natural killer cells. Health Conditions Related to Genetic Changes Systemic scleroderma Several normal variations in the IRF5 gene have been associated with an increased risk of developing systemic scleroderma, which is an autoimmune disorder characterized by the buildup of scar tissue (fibrosis) in the skin and internal organs. Although the IRF5 gene is known to stimulate the immune system in response to viruses, it is unknown how the gene variations contribute to the increased risk of systemic scleroderma. Researchers believe that a combination of genetic and environmental factors may play a role in development of the condition. Rheumatoid arthritis MedlinePlus Genetics provides information about Rheumatoid arthritis Systemic lupus erythematosus MedlinePlus Genetics provides information about Systemic lupus erythematosus Ulcerative colitis MedlinePlus Genetics provides information about Ulcerative colitis Reprinted from MedlinePlus Genetics (https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/) 1 Autoimmune disorders Studies have associated normal variations in the IRF5 gene with an increased risk of several autoimmune disorders. -

Heat Shock Factor 1 Mediates Latent HIV Reactivation

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Heat Shock Factor 1 Mediates Latent HIV Reactivation Xiao-Yan Pan1,*, Wei Zhao1,2,*, Xiao-Yun Zeng1, Jian Lin1, Min-Min Li3, Xin-Tian Shen1 & Shu-Wen Liu1,2 Received: 19 October 2015 HSF1, a conserved heat shock factor, has emerged as a key regulator of mammalian transcription Accepted: 29 April 2016 in response to cellular metabolic status and stress. To our knowledge, it is not known whether Published: 18 May 2016 HSF1 regulates viral transcription, particularly HIV-1 and its latent form. Here we reveal that HSF1 extensively participates in HIV transcription and is critical for HIV latent reactivation. Mode of action studies demonstrated that HSF1 binds to the HIV 5′-LTR to reactivate viral transcription and recruits a family of closely related multi-subunit complexes, including p300 and p-TEFb. And HSF1 recruits p300 for self-acetylation is also a committed step. The knockout of HSF1 impaired HIV transcription, whereas the conditional over-expression of HSF1 improved that. These findings demonstrate that HSF1 positively regulates the transcription of latent HIV, suggesting that it might be an important target for different therapeutic strategies aimed at a cure for HIV/AIDS. The long-lived latent viral reservoir of HIV-1 prevents its eradication and the development of a cure1. The recent combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) aimed at inhibiting viral enzymatic activities prevents HIV-1 repli- cation and halts the viral destruction of the host immune system2. However, proviruses in the latent reservoir persist in a transcriptionally inactive state, are insuppressible by cART and undetectable by the immune system3. -

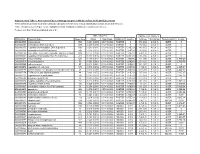

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

B-Cell Malignancies in Microrna Eμ-Mir-17∼92 Transgenic Mice

B-cell malignancies in microRNA Eμ-miR-17∼92 transgenic mice Sukhinder K. Sandhua, Matteo Fassana,b, Stefano Voliniaa,c, Francesca Lovata, Veronica Balattia, Yuri Pekarskya, and Carlo M. Crocea,1 aDepartment of Molecular Virology, Immunology and Medical Genetics, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH 43210; bARC-NET Research Centre, University of Verona, VR 37134, Verona, Italy; cDepartment of Morphology, Surgery and Experimental Medicine, University of Ferrara, FE 44121 Ferrara, Italy Contributed by Carlo M. Croce, September 22, 2013 (sent for review July 12, 2013) miR-17∼92 is a polycistronic microRNA (miR) cluster (consisting of cluster, but not of its paralogs, has shown that miR-17∼92 plays miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19a, miR-19b, miR-20a, and miR-92a) which an important role in B-cell development, and the KO mice die frequently is overexpressed in several solid and lymphoid malig- shortly after birth from lung hypoplasia and ventricular septal nancies. Loss- and gain-of-function studies have revealed the role defects (8). Further examination of the role of individual miRs in of miR-17∼92 in heart, lung, and B-cell development and in Myc- B-cell lymphomas showed that miR-19a and miR19b are required induced B-cell lymphomas, respectively. Recent studies indicate and sufficient for the proliferative activities of the cluster (9). that overexpression of this locus leads to lymphoproliferation, To understand better the role of the miR-17∼92 cluster in but no experimental proof that dysregulation of this cluster causes B-cell neoplastic progression, we generated miR-17∼92 B-cell– B-cell lymphomas or leukemias is available. -

Coactivation of NF-Kb and Notch Signaling Is Sufficient to Induce B

Regular Article LYMPHOID NEOPLASIA Coactivation of NF-kB and Notch signaling is sufficient to induce B-cell transformation and enables B-myeloid conversion Downloaded from https://ashpublications.org/blood/article-pdf/135/2/108/1550992/bloodbld2019001438.pdf by UNIV OF IOWA LIBRARIES user on 20 February 2020 Yan Xiu,1,* Qianze Dong,1,2,* Lin Fu,1,2 Aaron Bossler,1 Xiaobing Tang,1,2 Brendan Boyce,3 Nicholas Borcherding,1 Mariah Leidinger,1 Jose´ Luis Sardina,4,5 Hai-hui Xue,6 Qingchang Li,2 Andrew Feldman,7 Iannis Aifantis,8 Francesco Boccalatte,8 Lili Wang,9 Meiling Jin,9 Joseph Khoury,10 Wei Wang,10 Shimin Hu,10 Youzhong Yuan,11 Endi Wang,12 Ji Yuan,13 Siegfried Janz,14 John Colgan,15 Hasem Habelhah,1 Thomas Waldschmidt,1 Markus Muschen,¨ 9 Adam Bagg,16 Benjamin Darbro,17 and Chen Zhao1,18 1Department of Pathology, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA; 2Department of Pathology, China Medical University, Shenyang, China; 3Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY; 4Gene Regulation, Stem Cells and Cancer Program, Centre for Genomic Regulation, Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, Barcelona, Spain; 5Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute, Campus ICO-Germans Trias i Pujol, Barcelona, Spain; 6Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA; 7Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN; 8Department of Pathology, NYU School of Medicine,