The Snowball Warren Buffett and the Business of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

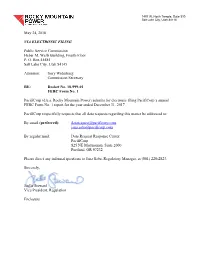

May 24, 2018 VIA ELECTRONIC FILING Public Service Commission

1407 W. North Temple, Suite 310 Salt Lake City, Utah 84116 May 24, 2018 VIA ELECTRONIC FILING Public Service Commission Heber M. Wells Building, Fourth Floor P. O. Box 45585 Salt Lake City, Utah 84145 Attention: Gary Widerburg Commission Secretary RE: Docket No. 18-999-01 FERC Form No. 1 PacifiCorp (d.b.a. Rocky Mountain Power) submits for electronic filing PacifiCorp’s annual FERC Form No. 1 report for the year ended December 31, 2017. PacifiCorp respectfully requests that all data requests regarding this matter be addressed to: By email (preferred): [email protected] [email protected] By regular mail: Data Request Response Center PacifiCorp 825 NE Multnomah, Suite 2000 Portland, OR 97232 Please direct any informal questions to Jana Saba, Regulatory Manager, at (801) 220-2823. Sincerely, Joelle Steward Vice President, Regulation Enclosure CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I hereby certify that on May 24, 2018, a true and correct copy of the foregoing was served by electronic mail and overnight delivery to the following: Utah Office of Consumer Services Cheryl Murray Utah Office of Consumer Services 160 East 300 South, 2nd Floor Salt Lake City, UT 84111 [email protected] Division of Public Utilities Erika Tedder Division of Public Utilities 160 East 300 South, 4th Floor Salt Lake City, UT 84111 [email protected] _____________________________ Jennifer Angell Supervisor, Regulatory Operations 1 THIS FILING IS Form 1 Approved OMB No.1902-0021 Item 1:X An Initial (Original) OR Resubmission No. ____ (Expires 12/31/2019) Submission Form 1-F Approved OMB No.1902-0029 (Expires 12/31/2019) Form 3-Q Approved OMB No.1902-0205 (Expires 12/31/2019) FERC FINANCIAL REPORT FERC FORM No. -

Phương Pháp Đầu Tư Warren Buffett Sẽ Tồn Tại Mãi Mãi Với Thời Gian

Robert G. Hagstrom PHONG CÁCH ĐẦU TƯ WARREN BUFFETT Bản quyền tiếng Việt © 2010 Công ty Sách Alpha NHÀ XUẤT BẢN LAO ĐỘNG - XÃ HỘI Dự án 1.000.000 ebook cho thiết bị di động Phát hành ebook: http://www.taisachhay.com Tạo ebook: Tô Hải Triều Ebook thực hiện dành cho những bạn chưa có điều kiện mua sách. Nếu bạn có khả năng hãy mua sách gốc để ủng hộ tác giả, người dịch và Nhà Xuất Bản MỤC LỤC PHONG CÁCH ĐẦU TƯ WARREN BUFFETT ................................................................ 2 Những lời khen ngợi dành cho cuốn sách .................................................................... 5 LỜI GIỚI THIỆU ....................................................................................................................... 7 LỜI TỰA .................................................................................................................................... 10 LỜI TỰA .................................................................................................................................... 12 LỜI MỞ ĐẦU ............................................................................................................................ 17 LỜI GIỚI THIỆU ..................................................................................................................... 21 1. NHÀ ĐẦU TƯ VĨ ĐẠI NHẤT THẾ GIỚI ..................................................................... 26 2. HỌC VẤN CỦA WARREN BUFFETT........................................................................... 35 3. “NGÀNH KINH DOANH CHÍNH CỦA CHÚNG TÔI -

The Complete Financial History of Berkshire Hathaway by Adam

The Complete Financial History of Berkshire Hathaway By Adam Mead Audiobook Companion Audiobook Contents (Charts included from the chapters below) Chapter 1: Textile Conglomerate Chapter 2: 1955–1964 Chapter 3: 1965–1974 Chapter 4: 1975–1984 Chapter 5: 1985–1994 Chapter 6: 1995–2004 Chapter 7: 2005–2014 Chapter 8: The First iftyF Years: 1965–2014 Chapter 9: 2015–2019 Chapter 10: World’s Greatest Conglomerate Chapter 11: Afterward—Berkshire After Buffett vii Figure 1.1: Millions of spindles in place by year and location 40 35 30 25 millions) 20 15 Spindles (in 10 5 0 1914 1925 1938 United States New England Massachusetts Southern States Source: The Decline Of A Cotton Textile City (Wolfbein p. 161). 12 Chapter 1: Textile Conglomerate Table 1.1: Comparative operational data for Berkshire Fine Spinning Associates and Hathaway Manufacturing Berkshire Fine Spinning Hathaway Manufacturing 1934 Net revenues ($ millions) $16.3 $3.9 Equity capital ($ millions) $13.8 $2.1 # spindles 900,000 79,000 # looms 20,000 3,200 1939 Net revenues ($ millions) $18.4 $7.3 Equity capital ($ millions) $13.1 $2.2 # spindles 748,000 62,000 # looms 15,000 2,800 1935–1939 (average) Return on equity 0% 6.10% Profit margin 1.40% 2.10% Revenues/average equity1 $1.34 $3.15 Footnote: Revenues/average equity calculation is from 1936–39 because no data is available for 1935 for Hathaway Manufacturing. Note: No data on 1939 for BFS, but spindles/looms same in 1938 and 1940. Sources: Moody’s Industrial Manuals 1934-40 and author’s calculations. 13 Chapter 1: Textile Conglomerate Figure 1.2: Revenues at Berkshire Fine Spinning and Hathaway Manufacturing from 1940–1949 $70 $60 $50 $40 $30 Revenues (millions) $20 $10 $0 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 Berkshire Fine Spinning Hathaway Manufacturing Sources: Moody’s Industrial Reports and Berkshire Hathaway Annual Reports. -

Alice Schroeder) Page 1 Variety of Roles in the Area of Professional Ethics, Accounting Standard-Setting, and Regulation

The Forging of a Skeptic - From Accountant to Buffett’s Voice on Wall St. http://seekingalpha.com/article/235292-behind-the-scenes-with-buffett-s-biographer-alice- schroeder Miguel: Hi Alice. I’d like to start by thanking you for taking the time to talk with me. Alice: Miguel, thanks for inviting me to do the interview. This is the first time I’ve ever talked to anyone at length about Warren Buffett, The Snowball, why I wrote the book, and the lessons learned. Miguel: Start by explaining what was special about your experience with The Snowball. Alice: When we discussed doing this interview, a theme that emerged was the hidden world of people like Warren Buffett, people who are in the top tenth of one percent of society in terms of fame, money, and connections, and how little most of us know of that world and its hierarchy and norms. Instinctively, you know that Snookie doesn’t go to parties with Bob Iger and Willow Bay (Disney CEO and his wife, a television host), but the more granular distinctions aren’t self- evident. For example, how valuable a form of social currency strong political connections in Washington can be, not because of their actual importance, but because they bring you reliably fresh and impressive-sounding conversational material to use at dinner parties. Even once inside a person’s world, getting to know their life history and psyche takes years, and that’s even truer of an important public figure because they’re so self-protective. Warren is so remote that his inner world has been accessible only to a tiny handful of people over the course of his lifetime, even though so many people are acquainted with him and consider him a friend. -

Confidence Game: How Hedge Fund Manager Bill Ackman Called Wall Streets Bluff Free Download

CONFIDENCE GAME: HOW HEDGE FUND MANAGER BILL ACKMAN CALLED WALL STREETS BLUFF FREE DOWNLOAD Christine S. Richard | 336 pages | 15 Apr 2011 | John Wiley & Sons Inc | 9781118010419 | English | New York, United States Hedge Fund Manager Wall Street was happy to deal with both the bond insurers and AIG because they appeared to be among the most creditworthy counterparties in the world. They got inside the house and scratched at the walls, keeping Washington awake at night. The Worst That Could Happen. Do you like that better than a model? Hedge fund managers and especially short sellers are all too often portrayed in a negative light. The model was dangerous. In recent months, Ackman had shared his analysis of MBIA with Einhorn, who had meanwhile been unusually public in his criticism of another company called Allied Capital Corporation, a firm that provided debt and equity financing to midsized companies. Why did the number of insured bonds guaranteed by MBIA and Confidence Game: How Hedge Fund Manager Bill Ackman Called Wall Streets Bluff below investment grade double in the last few quarters? The next afternoon, with the list of Caulis Negris properties in hand, I went out to see more. Where are they filed with the SEC? The financial markets, only recently recovered from the upheaval caused by the failure of Long Term Capital Management, could be thrown into turmoil again. By insuring a bond and stamping the triple-A credit rating on it, companies such as MBIA and Ambac turned the security into a kind of commodity that could be easily traded. -

Institutional Investor’S Selection of the Brokerage Analysts Who Have Done Outstanding Work During the Past Year Ranks 343 Researchers from 19 firms in 71 Sectors

COVER STORY LEFT TO RIGHT: Vivek Juneja, Mortgage Finance; Robin Farley, Leisure; Mark Connelly, Paper & Forest Products PHOTOGRAPHED ON AN OVERPASS ON WEST 39TH STREET, NEW YORK CITY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2003. Institutional Investor’s selection of the brokerage analysts who have done outstanding work during the past year ranks 343 researchers from 19 firms in 71 sectors. THE All-America RESEARCH TEAM wo years of investigations, disciplinary actions and internal CONTENTS crackdowns have drastically changed the life of Wall Street secu- THE LEADERS 70 OVERALL RESEARCH STRENGTH 98 rities analysts. Before the bubble burst researchers celebrated WEIGHTING THE RESULTS 98 their unprecedentedly high stature and compensation; now the WHAT INVESTORS REALLY WANT 100 T PICKING THE TEAM 106 dominant emotion inside most research departments is panic. Greed has THE BEST ANALYSTS OF THE YEAR given way to fear. BASIC MATERIALS 73 “People are scared,” says a 13-year veteran sell-side researcher, who in- CAPITAL GOODS/INDUSTRIALS 74 sisted that he and his firm not be identified. “That includes myself, my CONSUMER 78 sisted that he and his firm not be identified. “That includes myself, my ENERGY 85 colleagues here, other analysts I know elsewhere on the Street. Even if FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS 88 you’re completely honest, you’re scared that everyone’s watching and ready HEALTH CARE 90 MEDIA 94 to pounce on every little thing you say or do, whether it’s the regulators, TECHNOLOGY 96 the plaintiffs’ lawyers, the press or even your own compliance people.” TELECOMMUNICATIONS 100 MACRO 102 Fear can be a mixed blessing. On the positive side, the backlash against INDEXINDEX 108 108 PHOTOS BY EVAN KAFKA/REDUX Institutional Investor’s research teams are sponsored by Reuters. -

Cover Form2.Xlsx

Filed with the Iowa Utilities Board on May 30, 2019, M-0156 THIS FILING IS Form 2 Approved OMB No. 1902-0028 Item 1: X An Initial (Original) OR Resubmission No. (Expires 09/30/2017) Submission Form 3-Q: Approved OMB No. 1902-0205 (Expires 11/30/2016) FERC FINANCIAL REPORT FERC FORM No. 2: Annual Report of Major Natural Gas Companies and Supplemental Form 3-Q: Quarterly Financial Report These reports are mandatory under the Natural Gas Act, Sections 10(a), and 16 and 18 CFR Parts 260.1 and 260.300. Failure to report may result in criminal fines, civil penalities, and other sanctions as provided by law. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission does not consider these reports to be of a confidential nature. Exact Legal Name of Respondent (Company) Year/Period of Report End of 2018 MidAmerican Energy Company FERC FORM No. 2 2/3Q (02-04) Filed with the Iowa Utilities Board on May 30, 2019, M-0156 INSTRUCTIONS FOR FILING FERC FORMS 2, 2-A and 3-Q GENERAL INFORMATION I. Purpose FERC Forms 2, 2-A, and 3-Q are designed to collect financial and operational information form natural gas companies subject to the jurisdiction of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. These reports are also considered to be a non-confidential public use forms. II. Who Must Submit Each natural gas company whose combined gas transported or stored for a fee exceed 50 million dekatherms in each of the previous three years must submit FERC Form 2 and 3-Q. Each natural gas company not meeting the filing threshold for FERC Form 2, but having total gas sales or volume transactions exceeding 200,000 dekatherms in each of the previous three calendar years must submit FERC Form 2-A and 3-Q. -

Tapestry PDF: Advancing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion In

FS Large financial institutions are under pressure to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) across their organizations and in their client bases. The issue and efforts to address it are not new to financial services, but in the past year, the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on women and communities of color and the global Black Lives Matter movement have made prioritizing racial justice and employee and leadership diversity more urgent. Investors, employees, and customers are increasingly expecting more and better from institutions. This sense of urgency comes at a time when broader environmental, social, “I think the ‘S’ of and governance (ESG) issues, particularly around climate change, are also ESG is as important demanding more attention from firms. A director said, “I think the ‘S’ of ESG is as the climate as important as the climate change agenda and will get the same amount of change agenda and attention going forward.” Large banks and insurers have not historically had will get the same the most diverse workforces, especially among senior management, and they face unique challenges in recruiting diverse candidates. These financial amount of attention institutions play a distinctive role in economies and societies and have a going forward.” responsibility to be equitable in the way they serve an increasingly diverse customer base. Yet, despite decades of discussions and initiatives to improve – Director gender parity and promote diversity, progress has been slow. A director said, “If you aren’t considering DEI from the standpoint of both customers and employees, if you are not wrapping that into your business strategy, chances are you’re going to stumble somewhere.” As firms across the sector ponder next steps, they must confront long-standing cultural challenges and find ways to encourage inclusivity and equity. -

Alice Schroeder

Alice Schroeder Financial Columnist Author, The Snowball Bestselling author of The Snowball, Bloomberg View columnist, and corporate director Alice Schroeder is a former all-star securities analyst, CPA, and regulator with senior experience in nearly every part of the financial world. From the boardroom to startups to the scandals of the financial crisis, Schroeder explains the big picture and its transformative lessons from the perspective of an inside player on the global financial scene. Schroeder’s bestseller, The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life, is a revealing and complete look at the life of Buffett and the business secrets he never before shared publicly. The book debuted at #1 on The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Publisher’s Weekly bestseller lists. The Snowball has been called the “bible of capitalism” and “almost impossible to stop reading.” Named one of the best books of the year by TIME and The Financial Times, it was Amazon.com’s #1 Business and Investing Book of the year. The New York Times’ reviewer Janet Maslin hailed it as one of her top favorite books of the year, calling it a “definitive portrait.” Schroeder began her career as an auditor for Ernst & Young before becoming a regulator with the Financial Accounting Standards Board where she drafted some of the most significant accounting rules affecting the insurance industry. A former managing director at Morgan Stanley, she participated in key episodes of the financial crisis with AIG and MBIA, and was swept into the dramas at the investment banks, Berkshire Hathaway, and the rating agencies. -

2020 Annual Report (PDF File)

BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC. 2020 ANNUAL REPORT BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC. 2020 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Berkshire’s Performance vs. the S&P 500 ............................................... 2 Chairman’s Letter* ................................................................ 3-15 Form 10-K – Business Description ......................................................... K-1 Risk Factors ................................................................ K-22 Description of Properties ...................................................... K-26 Selected Financial Data ....................................................... K-32 Management’s Discussion ..................................................... K-33 Management’s Report on Internal Controls ....................................... K-66 Independent Auditor’s Report .................................................. K-67 Consolidated Financial Statements .............................................. K-70 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements ....................................... K-75 Appendices – Operating Companies ......................................................... A-1 Property/Casualty Insurance ................................................... A-2 Annual Meeting Information ................................................... A-3 Stock Transfer Agent ......................................................... A-3 Directors and Officers of the Company ............................................ Inside Back Cover *Copyright© 2021 By Warren E. Buffett All Rights Reserved -

Technology Is Driving Competitive Advantage in Financial Services (Pdf)

January 2021 Technology is driving competitive advantage in financial services The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated technology transformations in large financial institutions, as employees moved to remote work and as customers shifted to digital channels. Customers have come to expect uninterrupted, personalized digital products and services, adding to pressure as large financial institutions rework processes, accelerate investments, and explore new applications. A director said, “Legacy institutions, banks and insurers, are now moving much faster to improve customer experience because COVID-19 has accelerated the need to do that. They have to do this because traditional service solutions simply no longer work and will never work the same way again.”1 Technology transformation has been ongoing for some time, and the barriers “I think we need to and challenges are well known: the scale and cost of major upgrades, the spend wisely … but complexity created by legacy technology, institutional inertia, and regulatory we simply have to and compliance requirements. Though many of these underlying challenges stay in the race.” persist, attitudes are shifting; leaders recognize the need to move more quickly and to try new things. At the same time, technology has advanced in – Director ways that make more fundamental transformations faster and less costly, while also expanding opportunities for experimentation. A director said, “I think we need to spend wisely—you can waste a lot of money just as easily as investing correctly—but we simply have to stay in the race.” Financial institution leaders have an opportunity to learn and react. At the Financial Services Leadership Summit held on November 10–12, financial institution directors and executives, regulators, investors, and EY experts discussed how financial institutions have adapted to the pandemic and the options for firms as they accelerate broader systems upgrades to support new approaches. -

Fall 2008 the Advisor

DARDEN CAPITAL MANAGEMENT FALL 2008 THE ADVISOR Patrick Connell, Chief Investment Officer A Fall like None Other The financial crisis that rocked the capital markets over the past several months has been unprecedented on many levels. Darden Capital Management (DCM) was not immune to the crisis, particularly due to the fact that Lehman Brothers served as our prime broker. Lehman‘s collapse caused a substantial portion of DCM‘s assets to THIS ISSUE be frozen for months as the court appointed Trustee reconciled client accounts. THE STATE OF DCM Thankfully, DCM was able to transfer roughly $1.5mm in liquid assets out of Lehman Patrick Connell, CIO, documents a and all of the Jefferson Fund‘s securities prior to the bankruptcy, which allowed the turbulent, but successful, fall for DCM portfolio managers to continue to actively manage a portion of the club‘s assets during EXPANSION OF GUIDELINES several months of tremendous volatility in the markets. Several funds initiated tactical Andy Jamison, Portfolio Manager, explains hedges to limit the downside of their portfolios and, in some cases, portfolio managers recent changes to DCM guidelines decided to add to certain positions that fell considerably below their intrinsic value. STOCK PITCH EVENTS After over two months of waiting as the bankruptcy was processed, DCM was able to John Imbriglia, Director of Research, reports gain control of the majority of its assets in late November. We are now working with on a record turnout for DCM’s 4th Annual Stock Pitch Competition Darden‘s counsel to reclaim the remainder of our assets, which represent less than 5% of the aggregate portfolio value.