The Fusion of History and Literature in Richard Wright and James T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pete Segall. the Voice of Chicago in the 20Th Century: a Selective Bibliographic Essay

Pete Segall. The Voice of Chicago in the 20th Century: A Selective Bibliographic Essay. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. December, 2006. 66 pages. Advisor: Dr. David Carr Examining the literature of Chicago in the 20th Century both historically and critically, this bibliography attempts to find commonalities of voice in a list of selected works. The paper first looks at Chicago in a broader context, focusing particularly on perceptions of the city: both Chicago’s image of itself and the world’s of it. A series of criteria for inclusion in the bibliography are laid out, and with that a mention of several of the works that were considered but ultimately disqualified or excluded. Before looking into the Voice of the city, Chicago’s history is succinctly summarized in a bibliography of general histories as well as of seminal and crucial events. The bibliography searching for Chicago’s voice presents ten books chronologically, from 1894 to 2002, a close examination of those works does reveal themes and ideas integral to Chicago’s identity. Headings: Chicago (Ill.) – Bibliography Chicago (Ill.) – Bibliography – Critical Chicago (Ill.) – History Chicago (Ill.) – Fiction THE VOICE OF CHICAGO IN THE 20TH CENTURY: A SELECTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHIC ESSAY by Pete Segall A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina December 2006 Approved by _______________________________________ Dr. David Carr 1 INTRODUCTION As of this moment, a comprehensive bibliography on the City of Chicago does not exist. -

An Evening to Honor Gene Wolfe

AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE Program 4:00 p.m. Open tour of the Sanfilippo Collection 5:30 p.m. Fuller Award Ceremony Welcome and introduction: Gary K. Wolfe, Master of Ceremonies Presentation of the Fuller Award to Gene Wolfe: Neil Gaiman Acceptance speech: Gene Wolfe Audio play of Gene Wolfe’s “The Toy Theater,” adapted by Lawrence Santoro, accompanied by R. Jelani Eddington, performed by Terra Mysterium Organ performance: R. Jelani Eddington Closing comments: Gary K. Wolfe Shuttle to the Carousel Pavilion for guests with dinner tickets 8:00 p.m Dinner Opening comments: Peter Sagal, Toastmaster Speeches and toasts by special guests, family, and friends Following the dinner program, guests are invited to explore the collection in the Carousel Pavilion and enjoy the dessert table, coffee station and specialty cordials. 1 AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE By Valya Dudycz Lupescu A Gene Wolfe story seduces and challenges its readers. It lures them into landscapes authentic in detail and populated with all manner of rich characters, only to shatter the readers’ expectations and leave them questioning their perceptions. A Gene Wolfe story embeds stories within stories, dreams within memories, and truths within lies. It coaxes its readers into a safe place with familiar faces, then leads them to the edge of an abyss and disappears with the whisper of a promise. Often classified as Science Fiction or Fantasy, a Gene Wolfe story is as likely to dip into science as it is to make a literary allusion or religious metaphor. A Gene Wolfe story is fantastic in all senses of the word. -

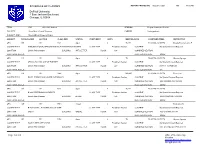

SCHEDULE of CLASSES Depaul University 1 East Jackson

SCHEDULE OF CLASSES REPORT PRINTED ON: August 13, 2021 AT: 11:42 AM DePaul University 1 East Jackson Boulevard Chicago, IL 60604 TERM: 1080 2021-2022 Autumn SESSION: Regular Academic Session COLLEGE: Liberal Arts & Social Sciences CAREER: Undergraduate SUBJECT AREA: African&Black Diaspora Studies SUBJECT CATALOG NBR SECTION CLASS NBR STATUS COMPONENT UNITS MEETING DAYS START/END TIMES INSTRUCTOR ABD 100 101 1821 Open 4 TU TH 11:20 AM - 12:50 PM Moody-Freeman,Julie E COURSE TITLE: INTRODUCTION TO AFRICAN AND BLACK DIASPORA STUDIES CLASS TYPE: Enrollment Section CONSENT: No Special Consent Required LOCATION: Lincoln Park Campus BUILDING: ARTSLETTER ROOM: 408 COMBINED SECTION: ADDITIONAL NOTES: REQ DESIGNATION: SSMW ABD 211 101 1638 Open 4 TU 05:45 PM - 09:00 PM Otunnu,Ogenga COURSE TITLE: AFRICA TO 1800: AGE OF EMPIRES CLASS TYPE: Enrollment Section CONSENT: No Special Consent Required LOCATION: Lincoln Park Campus BUILDING: ARTSLETTER ROOM: 207 COMBINED SECTION: HST131 701/ABD 211 ADDITIONAL NOTES: REQ DESIGNATION: UP ABD 229 101 2088 Open 4 MO WE 11:20 AM - 12:50 PM Pierce,Lori COURSE TITLE: RACE, SCIENCE AND WHITE SUPREMACY CLASS TYPE: Enrollment Section CONSENT: No Special Consent Required LOCATION: Lincoln Park Campus BUILDING: ARTSLETTER ROOM: 109 COMBINED SECTION: ABD 229/AMS 297/PAX 290 ADDITIONAL NOTES: REQ DESIGNATION: SSMW ABD 236 101 6821 Open 4 TU TH 01:00 PM - 02:30 PM COURSE TITLE: BLACK FREEDOM MOVEMENTS CLASS TYPE: Enrollment Section CONSENT: No Special Consent Required LOCATION: Lincoln Park Campus BUILDING: LEVAN ROOM: -

Angela Jackson

This program is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. ANGELA JACKSON A renowned Chicago poet, novelist, play- wright, and biographer, Angela Jackson published her first book while still a stu- dent at Northwestern University. Though Jackson has achieved acclaim in multi- ple genres, and plans in the near future to add short stories and memoir to her oeuvre, she first and foremost considers herself a poet. The Poetry Foundation website notes that “Jackson’s free verse poems weave myth and life experience, conversation, and invocation.” She is also renown for her passionate and skilled Photo by Toya Werner-Martin public poetry readings. Born on July 25, 1951, in Greenville, Mississippi, Jackson moved with her fam- ily to Chicago’s South Side at the age of one. Jackson’s father, George Jackson, Sr., and mother, Angeline Robinson, raised nine children, of which Angela was the middle child. Jackson did her primary education at St. Anne’s Catholic School and her high school work at Loretto Academy, where she earned a pre-medicine scholar- ship to Northwestern University. Jackson switched majors and graduated with a B.A. in English and American Literature from Northwestern University in 1977. She later earned her M.A. in Latin American and Caribbean studies from the University of Chicago, and, more recently, received an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Bennington College. While at Northwestern, Jackson joined the Organization for Black American Culture (OBAC), where she matured under the guidance of legendary literary figures such as Hoyt W Fuller. -

London and Chicago in Literature Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi

F. Dinçer / Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi XIX (1), 2006, 89-104 Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi http://kutuphane. uludag. edu. tr/Univder/uufader. htm London and Chicago in Literature Figun Dinçer Uludağ Üniversitesi, Eğitim Fakültesi [email protected] Abstract. This study aims to illustrate how London and Chicago are depicted in literature in the 19th. Century and the first quarter of the 20th. Century. Six literary works are selected from English and American Literature that contain information about the city life. These prominent writers are William Blake, Thomas Hood, Matthew Arnold, William Wordsworth, Carl Sandburg and Upton Sinclair. The works can be evaluated from different aspects but the focus of this study is specifically on the social problems caused by industrialization and urbanization. The paper is organized in two parts. In the first part, it draws a general picture of urban and industrial developments in England and the States, and the portraits of London and Chicago in that period, and in the second part, the works are discussed in order to see how the cities are depicted. The evaluation is approached through Marxist literary criticism. Key Words: Industrialization, urbanization, London, Chicago, literature. Özet. Bu çalışma, Londra ve Chicago’nun, 19.yüzyılda ve 20. yüzyılın ilk çeyreğinde, edebiyatta nasıl ele alındığını göstermeyi amaçlıyor. İngiliz ve Amerikan Edebiyatından, kent yaşamını anlatan altı eser seçilmiştir. William Blake, Thomas Hood, Matthew Arnold, William Wordsworth, Carl Sandburg ve Upton Sinclair seçilen seçkin yazarlardır. Eserler, farklı 89 F. Dinçer / Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi XIX (1), 2006, 89-104 açılardan ele alınabilir, ama bu çalışma özellikle sanayileşme ve kentleş- menin neden olduğu toplumsal sorunlara odaklanmıştır. -

SCHOOL PROFILE 2017-2018 Head of School: Jason Patera 1010 W

SCHOOL PROFILE 2017-2018 Head of School: Jason Patera 1010 W. Chicago Ave. Chicago, IL 60642-5414 [email protected] P: 312.421.0202 College Counselor: Sarah Langford F: 312.421.3816 [email protected] chicagoacademyforthearts.org Dean of Students: Elizabeth Cunningham CEEB/ACT Code: 140-627 [email protected] ABOUT THE CHICAGO ACADEMY FOR THE ARTS Established in 1981, The Chicago Academy for the Arts is a nationally recognized, internationally influential independent high school acclaimed for its unique co-curricular program composed of rigorous college-preparatory academics and professional- level arts training. Designated a National School of Distinction by the John F. Kennedy Center, The Chicago Academy for the Arts provides a challenging and stimulating environment in which young scholar-artists master the skills necessary for academic success, critical thought, and creative expression. MISSION FACULTY ACADEMIC CURRICULUM The Chicago Academy for the Arts The Academy’s faculty consists of 55 The Academy’s rigorous, college- transforms emerging artists through a members, including full-time, certified preparatory academic program is curriculum and culture which connect academic teachers and arts instructors, built upon core studies in English, intellectual curiosity, critical thinking, as well as part-time artist-teachers mathematics, science, social studies, and creativity to impart the skills to of local, national, and international and world languages. Honors courses lead and collaborate across diverse acclaim. The student-to-faculty ratio are offered in selected disciplines. AP communities. is 4:1. Fifty-three percent of Academy courses are offered during a student’s teachers hold graduate degrees. junior and senior years. STUDENT BODY Students are admitted to The Academy ACCREDITATION each year based on demonstrated The Academy is accredited by the ability in both academics and the arts. -

Newberry Seminars

FALL 2016 Newberry Seminars Picturing America: Art in the United States Arts, Music, and Language from the Colonial Period to the Civil War From Bach to Brahms: New Skills for Wednesdays, 11 am - 1 pm From Bach to Brahms: New Skills for Enhanced Listening September 14 - October 26 Enhanced Listening Tuesdays, 2 - 4 pm This seminar will explore early American art September 13 - November 8 from the colonial period to the Civil War, (class will not meet October 11) decades of dramatic upheaval that witnessed the Everyone can have a new and enriched experi- birth of a new nation, Western expansion, and Everyone can have a new and enriched experi- a rapidly changing society. Sessions will focus ence with each visit toto thethe concertconcert hall.hall. BelieveBelieve itit or not, one’s listening skills can be improved with on visual analysis of works of art, as well as or not, one’s listening skills can be improved with discussions of primary and secondary sources that just pen and paper.paper. ThisThis coursecourse resemblesresembles “Music“Music 101,” but with a novel twist: the visualization of illuminate the historic and cultural context of the 101,” but with a novel twist: the visualization of works’ production. Artists to be discussed include thematic material. OurOur journeyjourney willwill provideprovide anan overview of J.S. Bach and the Baroque, Haydn Copley, West, Homer, and individuals associated overview of J.S. Bach and the Baroque, Haydn with the Hudson River School. Information and Mozart as representatives ofof thethe ClassicalClassical period, Beethoven as the bridge to Romanticism, about first readings will be sent upon registration. -

Program of Studies 2020–2021

1 UNIVERSITY HIGH SCHOOL PROGRAM OF STUDIES 2020–2021 Table of Contents > Introduction…………………………..…………………………………....………………...…3 > Graduation Requirements…………….………………………………………………..….……4 > Examples of Four-year Programs………………………………………………………………5 > Grades and Grade Point Averages……………………………………………………....…….. 6 > Schedule Changes: Adding and Dropping of Courses………………………….………….......7 > Advisory Program…………………………………………………………………………..…. 9 > Counselor Programming………………………………………………………………………10 > Pritzker Traubert Family Library………………………………………………………….….12 > English…………………………………………………………………………………...……13 > History……………………………………………………………………………………….. 20 > Mathematics……………………………………………………………….…………………. 34 > Science…………………………………………………………………………..…………… 41 > World Languages…………………………………………………………………………….. 48 Chinese…………………………………………………………………………….…… 51 French…………………………………………………………………………….……..54 German……………………………………………………………………………..…... 57 Greek……………………………………………………………………………….…... 60 Latin………………………………………………………………………..……………61 Spanish……………………………………………………………..……………....……63 Non-Language Elective…………………………………………………………..……..67 > Computer Science………………………………………………………………….………… 68 > Fine Arts…………………………………………………………………..…………………. 73 Courses in the Visual Arts……………………....……………………...……………….74 Courses in the Dramatic Arts……………………………………………………...…… 80 > Music……………………………………………………………………....………………….83 Courses that fulfill the music credit requirement Music Department Electives > Journalism………………………………………………………………………………….… -

European Journal of American Studies , Reviews 2020-4 Michelle E

European journal of American studies Reviews 2020-4 Michelle E. Moore, Chicago and the Making of American Modernism. Cather, Hemingway, Faulkner, and Fitzgerald in Conflict Andreas Hübner Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/16632 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Andreas Hübner, “Michelle E. Moore, Chicago and the Making of American Modernism. Cather, Hemingway, Faulkner, and Fitzgerald in Conflict”, European journal of American studies [Online], Reviews 2020-4, Online since 18 December 2020, connection on 09 July 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/ejas/16632 This text was automatically generated on 9 July 2021. Creative Commons License Michelle E. Moore, Chicago and the Making of American Modernism. Cather, Hemi... 1 Michelle E. Moore, Chicago and the Making of American Modernism. Cather, Hemingway, Faulkner, and Fitzgerald in Conflict Andreas Hübner 1 Michelle E. Moore, Chicago and the Making of American Modernism. Cather, Hemingway, Faulkner, and Fitzgerald in Conflict 2 London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. Pp. 247. ISBN: 9781350018037 3 Andreas Hübner, Leuphana University Lüneburg 4 American modernist writers are rarely associated with turn-of-the-century Chicago and its literary scene. In the decades after the Great Fire of 1871, the city built a profit- centered reputation modernist writers were typically trying to resist. In Chicago, patronage and commercial boosterism lingered alongside evangelicalism and provincialism, even as city leaders envisioned a “higher life”: a spiritual, physical, and artistic evolution of Chicago. Art and literary projects were to showcase the city’s cultural progress; museums, symphonies, and operas to improve the city’s status. In this atmosphere, literary realism began to flourish in Chicago, thrived during the days of the World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893, and continued to reign thereafter, with writers such as Theodore Dreiser and Henry Blake Fuller at the forefront. -

Literature (LIT) 1

Literature (LIT) 1 LITERATURE (LIT) LIT 306 LIT 328 Science Fiction Poetry A treatment of select science fiction texts in terms of how they Study of poetry and imaginative prose, including an analysis of the reflect shifting forms of work and social life in the 20th century. theoretical, literary, and socio-cultural contexts of these works. The The course will focus on how these texts translate shifts in social course may include creative writing by students. patterns and popular entertainment. Prerequisite(s): HUM 102 or HUM 104 or HUM 106 or HUM 200-299 Prerequisite(s): HUM 102 or HUM 104 or HUM 106 or HUM 200-299 Lecture: 3 Lab: 0 Credits: 3 Lecture: 3 Lab: 0 Credits: 3 Satisfies: Communications (C), Humanities (H) Satisfies: Communications (C), Humanities (H) LIT 339 LIT 307 Shakespeare on Stage and Screen Graphic Novel While reading is the first step in understanding Shakespeare's work, Comics, once a genre associated primarily with superheroes, have seeing his words brought to life in a film or stage production comes evolved since the 1970's to address weighty philosophical and closest to experiencing the plays as Shakespeare intended 400 existential issues in extended formats such as the graphic novel. years ago: as a performance. For each play discussed, students will This course will examine the graphic novels from major authors in view and compare two film versions. Students will also go to a live the genre (e.g., Spiegelman, Eisner, and Moore) as well as "outside" production of one play. Also covered are a history of Shakespeare artists. -

Material of American Literature. Akira Yajima 一

Significa nce of Chica go a s the Material of American Literature. Akira Yajima Faculty of Sociology, Ohara Seminar. Hail to thee, fair Chicago!On thy brow America, thy mother, lays a crown. Bravest among her daughters art thou, Most strong of all her heirs of high renown. -Harliet Monroe. 1. First, we take a look at the“Chicago Renaissance”in American literature. What we call here the Chicago Renaissance is that big and rapid change marked on the map of American literature during the period spanning from 1890 to 1920. It is at once a qualitative change in the literary mode and a regional change on the literary map of the United States. The qualitateve change means in short the emergence of naturalism and later realism versus romanticism. In the conventio’nal opinion the rise of naturalism in Alnerica is attributed partly to the lnfluences of European and Russian writers, namely, Zola, Flaubert, Hardy, Tolstoi and lnany others. But it is not so clear what decisive influences they had upon American writers of the age in regard to their literary techniques and points of view. What Mencken said about the“essential iso玉ation of Dreiser”is to some extent applicable to other writers. Their naturalism is essentially the Americall naturalism. 101 一 The regiona互change, which stands in a close co皿ection to the former, comes under the headline of the appearance of the West and the Middlewest on to the stage of American literature. Approximately none of virtually non-New England・Eastern American literature had been existing unti11880s. Since the -

Book Reviews 39 1 Chicago and the American

Book Reviews 39 1 Chicago and the American Literary Imagination, 1880-1920. By Carl S. Smith. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984. Pp. xiv, 232. Illustrations, appendix, notes, bibliography, in- dex. Paperbound, $8.95.) Each word in Carl Smith’s title is telling. He has not writ- ten a history of Chicago literature but rather a more interesting study of the impact of Chicago on the imagination of writers in the crucial years 1880-1920. What did Chicago mean to writers? By examining not only works of fiction but also autobiography, travel books, guidebooks, histories, and muckraking criticism, Smith defines literature broadly and shows how a wide range of writers portrayed life in this quintessentially American city. He is particularly interested in texts which “directly and indirectly discussed the relationship of literature, art, and urban life” (pp. xi-xii). Part One describes how Chicago writers, in struggling for words to express their response to the industrial city, created works in which an artist protagonist seeks a place in raw Chicago, usually unsuccessfully. These writers thereby revealed the tension that they themselves experienced in both living in Chicago and trying to write about it. After examining Jane Addams’s plea for an integration of life and art, Smith turns to works by E. P. Roe, Henry Blake Fuller, Robert Herrick, and Will Payne; all but Roe were less optimistic than Addams that art could survive in materialistic Chicago. If male artists fail, women who aspire to culture fare no better, whether as artists themselves or as consumers of art. Either they retreat to domesticity or, like Theodore Dreiser’s Carrie Meeber, they become victims of their own drive to suc- ceed.