Optimising the Location of Antenatal Classes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leeds City Council Standards Committee Annual Report 2009

Leeds City Council Standards Committee Annual Report 2009 – 2010 Introduction The Local Government Act 2000 requires councils to set up a standards committee. Standards committees have a proactive role in creating an ethical framework which governs the relationship between high standards of conduct and transparency and openness in decision making. As a result of the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007 and the Standards Committee (England) Regulations 2008, the role of the Standards Committee also includes the local assessment of complaints made under the Member Code of Conduct. This is the Committee’s fifth Annual Report and it presents a summary of its work during the 2009-10 municipal year. The Committee’s Annual Return to Standards for England is appended to the report. This report supports the corporate governance arrangements of the Council by promoting good conduct and cascading information. Our Ambition “To help develop and maintain a climate of mutual trust and respect in which Members, officers and partners work effectively together to deliver the Council’s strategic and operational priorities and where the public can be assured that this is done in an honest, objective and accountable way.” 2 Foreword from the Chair Leeds City Council was announced as winner of the Standards and Ethics category at the Local Government Chronicle Awards 2010. The judging panel was impressed by the Leeds approach to ethical governance within the authority, and its commitment to promoting and maintaining high standards of Member conduct. Features of our work were also highlighted as a case study of notable practice in Standards for England’s most recent Annual Review. -

Properties for Customers of the Leeds Homes Register

Welcome to our weekly list of available properties for customers of the Leeds Homes Register. Bidding finishes Monday at 11.59pm. For further information on the properties listed below, how to bid and how they are let please check our website www.leedshomes.org.uk or telephone 0113 222 4413. Please have your application number and CBL references to hand. Alternatively, you can call into your local One Stop Centre or Community Hub for assistance. Date of Registration (DOR) : Homes advertised as date of registration (DOR) will be let to the bidder with the earliest date of registration and a local c onnection to the Ward area. Successful bidders will need to provide proof of local connection within 3 days of it being requested. Maps of Ward areas can be found at www.leeds.gov.uk/wardmaps Aug 4 2021 to Aug 9 2021 Ref Landlord Address Area Beds Type Sheltered Adapted Rent Description DOR Beech View , Aberford , Leeds, LS25 Single/couple 10984 Leeds City Council 3BW Harewood 1 Bungalow No No 88.49 No LANDSEER ROAD, BRAMLEY, LEEDS, Single person or couple 10987 Leeds City Council LS13 2QP Bramley and Stanningley 1 Flat No No 66.26 No COTTINGLEY TOWERS, Cottingley Single person or couple 10989 Leeds City Council Drive , Beeston , Leeds , LS11 0JH Beeston and Holbeck 1 Flat No No 69.44 No KINGSWAY, DRIGHLINGTON, Single person or couple 10993 Leeds City Council BRADFORD, LEEDS, BD11 1ET Morley North 1 Flat No No 66.30 No NEWHALL GARDENS, MIDDLETON, Single/couple 11000 Leeds City Council LEEDS, LS10 3TF Middleton Park 1 Flat No No 63.52 No NORTH -

May 2021 FOI 2387-21 Drink Spiking

Our ref: 2387/21 Figures for incidents of drink spiking in your region over the last 5 years (year by year) I would appreciate it if the figures can be broken down to the nearest city/town. Can you also tell me the number of prosecutions there have been for the above offences and how many of those resulted in a conviction? Please see the attached document. West Yorkshire Police receive reports of crimes that have occurred following a victim having their drink spiked, crimes such as rape, sexual assault, violence with or without injury and theft. West Yorkshire Police take all offences seriously and will ensure that all reports are investigated. Specifically for victims of rape and serious sexual offences, depending on when the offence occurred, they would be offered an examination at our Sexual Assault Referral Centre, where forensic samples, including a blood sample for toxicology can be taken, with the victim’s consent, if within the timeframes and guidance from the Faculty for Forensic and Legal Medicine. West Yorkshire Police work with support agencies to ensure that all victims of crime are offered support through the criminal justice process, including specialist support such as from Independent Sexual Violence Advisors. Recorded crime relating to spiked drinks, 01/01/2016 to 31/12/2020 Notes Data represents the number of crimes recorded during the period which: - were not subsequently cancelled - contain the search term %DR_NK%SPIK% or %SPIK%DR_NK% within the crime notes, crime summary and/or MO - specifically related to a drug/poison/other noxious substance having been placed in a drink No restrictions were placed on the type of drink, the type of drug/poison or the motivation behind the act (i.e. -

The Leeds (Electoral Changes) Order 2017

Draft Order laid before Parliament under section 59(9) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009; draft to lie for forty days pursuant to section 6(1) of the Statutory Instruments Act 1946, during which period either House of Parliament may resolve that the Order be not made. DRAFT STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2017 No. LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Leeds (Electoral Changes) Order 2017 Made - - - - *** Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) and (3) Under section 58(4) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009( a) (“the Act”), the Local Government Boundary Commission for England( b) (“the Commission”) published a report dated March 2017 stating its recommendations for changes to the electoral arrangements for the city of Leeds. The Commission has decided to give effect to those recommendations. A draft of the instrument has been laid before each House of Parliament, a period of forty days has expired since the day on which it was laid and neither House has resolved that the instrument be not made. The Commission makes the following Order in exercise of the power conferred by section 59(1) of the Act. Citation and commencement 1. —(1) This Order may be cited as the Leeds (Electoral Changes) Order 2017. (2) This article and article 2 come into force on the day after the day on which this Order is made. (3) The remainder of this Order comes into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary, or relating, to the election of councillors, on the day after the day on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in England and Wales( c) in 2018. -

News Release

News Release 2 May 2008 LEEDS LOCAL ELECTION RESULTS - 2008 Results have been confirmed in the local elections for Leeds City Council. Of the 34 seats contested – one in each ward except in Calverley and Farsley ward where there was a double vacancy – Labour have 13, Conservative 9, Liberal Democrat 9, Green Party 1, Morley Borough Independent 2. Taking into account the council’s total 99 seats, the political composition of Leeds City Council is now as follows: Labour 43, Liberal Democrat 24, Conservative 22, Morley Borough Independent 5, Green Party 3, Independent 1, BNP 1. Voter turnout was approximately 35.76%, as compared to 37.52% in 2007. Full results are below, listed in alphabetical order by ward. Total percentage of votes by party are as follows: Party Percentage votes by party Conservative 31.41% Labour 28.67% Liberal Democratic 18.89% BNP 11.35% Green 3.72% Morley Borough Independents 3.19% Alliance for Green Socialism 0.97% UK Independent Party 0.9% Independent 0.77% English Democrats ‘Putting England First’ 0.14 Corporate Communications, Civic Hall, Leeds LS1 1UR Tel. 0113 247 4328 Fax. 0113 247 4736 For more news and information from Leeds City Council visit www.leeds.gov.uk www.leeds.gov.uk Switchboard : 0113 234 8080 Full details of the results are available on the Leeds City Council website, www.leeds.gov.uk/elections Local Elections 2008 - Results Adel and Wharfedale Ward Elected: BARRY JOHN ANDERSON Turnout: 47.62% Surname Other Names Party Votes ANDERSON BARRY JOHN CONSERVATIVE 4377 JASON BRITISH NATIONAL PARTY 269 HARLAND DOREEN ILLINGWORTH LABOUR 727 VALERIE PAUL MARCHANT GREEN PARTY 202 RICHARD SHAW CHRISTINA LIBERAL DEMOCRATS 2020 Alwoodley Ward Elected: RONNIE FELDMAN Turnout: 40.68% Surname Other Names Party Votes CLAY JOHN LIBERAL DEMOCRATS 1041 FELDMAN RONNIE CONSERVATIVE 4059 HENDON WARREN UK INDEPENDENCE PARTY 250 ALLIANCE FOR GREEN JACKSON BRIAN 174 SOCIALISM MASTERTON DOUG LABOUR 1390 WHITAKER CHRISTINE BRITISH NATIONAL PARTY 228 Corporate Communications, Civic Hall, Leeds LS1 1UR Tel. -

Download the List of Councillors Ward by Ward

The Thoresby Society The Leeds Historical Society founded in 1889 Leeds City Councillors 1980-2021 Ward by Ward with an alphabetical index of names This document lists for each Ward its Councillors from 1980 onwards. The lists of Councillors are ordered first by the date of their first election, then by their length of service, and then alphabetically. There are Leeds City Council elections in three years out of four, with no elections in 1981, 1985, 1989 and so on, except that because of the Covid pandemic, there were no elections in2020, but elections in 2021. The elections in 1980, 2004 and 2018 were contested on new ward boundaries, with three seats up for election in each ward. In other years only one seat was up for election in each ward, except in a few cases when there was also a casual vacancy to be filled. Sometimes when the boundaries of a ward were changed, its name also changed. The years from 1980 in which a ward of a given name existed are given after the name. Current wards are listed first, followed by former wards. The lists of Councillors by ward are followed by an alphabetical index of all the Councillors elected in the given period. Leaders of the Council 1980-1989 George Mudie (Labour) 1989-1996 Jon Trickett (Labour) 1996-2003 Brian Walker (Labour) 2003-2004 Keith Wakefield (Labour) 2004-2007 Mark Harris (Liberal Democrat) [Joint Leader] 2004-2010 Andrew Carter (Conservative) [Joint Leader] 2007-2010 Richard Brett (Liberal Democrat) [Joint Leader] 2010-2015 Keith Wakefield (Labour) 2015-2021 Judith Blake (Labour) 2021- James Lewis (Labout) It is too much to be hoped that this document contains no errors. -

Leeds' Newcomers in 2019

Leeds’ newcomers in 2019 A short statistics overview for people who plan or deliver services, and are planning for migrants who are the newest arrivals to Leeds. Photo credits: Steve Morgan [photographer] and Yorkshire Futures [source]. 1. Introduction Who is this briefing paper for? This document is aimed at people who plan or deliver local services in Leeds. You might find you are often the first people who meet and respond to newcomers in the local area. You will know that people who have just arrived in an area often need more information and support than those who have had time to adjust and learn about life in the UK. These newcomers might benefit from information about key services for example, in their first language. This briefing paper provides an overview of the numbers and geographical patterns of new migrants who recently have come to live in Leeds and were issued with a national insurance number [NINO] in 2019. We hope you will find the information presented here useful for planning services and engagement with new communities, making funding applications, or for background research for you or your colleagues to better understand migration in your area. Where has the data come from? This briefing paper was produced by Migration Yorkshire in September 2020. This document uses information from the Department for Work and Pensions [DWP] about non-British nationals who successfully applied for a NINO in 2019. We have used this as a proxy for newcomers, because new arrivals usually need to apply for a NINO in order to work or claim benefits. -

Morley Town Investment Plan Projects Map LEEDS CITY COUNCIL (Accountable MORLEY TOWN DEAL BOARD Body, Delivery Body)

Town Investment Plan 2021 Contents 01. Executive Summary 2 02. Vision and Objectives 4 03. Our Town 10 04. Strategy 30 05. Engagement and Delivery 34 06. Projects 48 Credit for photos: Kate Campbell of Campbell’s Photography - www.campbellsphotography.co.uk Executive Summary Morley is a town of approximately 31,600 Morley has a strong asset base: historic people five miles south-west of Leeds City buildings01 that are a positive legacy of its past Centre. A district in its own right until the success, a rail station connecting the town to 1970s and now forming part of the Leeds Leeds and Manchester, a swathe of green belt metropolitan district, Morley has retained that helps preserves its distinctive identity distinctiveness, sense of civic pride and within the Leeds Metropolitan area, and a community identity. A place of huge potential, string of employment hubs that frame its this investment plan will enable the town to eastern boundary. Yet these assets have not build on its sense of identity and capitalise on driven the growth of opportunity or economic its great history while confidently facing the uplift that they could. Many of the town’s future. heritage buildings are vacant or underused, its station is disconnected from the town and is inaccessible to many residents. The town lacks meaningful greenspace provision This Town Investment and has low tree canopy coverage, and the Plan sets out a employment hubs are poorly connected to strategy to build the town and its residents. As a result, Morley faces core challenges relating to its economic upon the proud and resilience, health and wellbeing, declining successful history built environment and skills levels. -

MORLEY NORTH WARD Ward As a Place: Drighlington; Gildersome; Churwell; Morley Bottoms

MORLEY NORTH WARD Ward as a place: Drighlington; Gildersome; Churwell; Morley Bottoms Population Ethnicity Age 0-15 (18.08%) White/British 95% Age 16 - 64 (62.81%) Asian/British 2.8% Age 65+ (19.12%) Black/British 0.5% Mixed/Other 1.6% Socio-economic/demographic Morley North is predominantly white British with an average to high quality of life, which masks a number of ‘pockets’ of deprivation across the area. These ‘pockets’ are neighbourhoods such as Oakwells and Fairfax in Drighlington, the Ingles in Morley, and Springbank and Moorlands in Gildersome. These neighbourhoods are characterised by lower skills levels, health problems and poor education attainment. Ward population is 21,230 people living in approximately 9,400 households. Housing: Private - Other Rented Flat, maisonette Private - landlord/letting agency Rented HA, Registered Landlord Terraced Leeds (%) Council Leeds (%) Morley North (%) Semi detached Morley North (%) Shared ownership Own (mortgage/loan) Detached Own outright Owner Occupied 0.0 10.0 20.0 30.0 40.0 50.0 0.0 10.0 20.0 30.0 40.0 50.0 Main Council Facilities (including Key Local Organisations parks, visitor attractions etc.) Morley Town Council; Drighlington Parish Council; Drighlington Library; Gildersome Library; Gildersome and Gildersome Parish Council; Gildersome Action Group; Drighlington Children’s Centre; Morley North Children’s Churwell Action Group; Morley Elderly Action; Centre; Stanhope Community Centre; Gildersome Youth Oakwells and Fairfax Tenants and Residents Centre; Drighlington Meeting Hall; Multi Use Games Association Area, Drighlington; Play area, Gildersome Key Challenges Main Non-Council Facilities Local action groups campaign to promote and protect White Rose Shopping Centre; The Manor Golf Club, the amenities and the environment. -

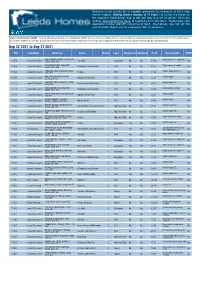

Properties for Customers of the Leeds Homes Register

Welcome to our weekly list of available properties for customers of the Leeds Homes Register. Bidding finishes Monday at 11.59pm. For further information on the properties listed below, how to bid and how they are let please check our website www.leedshomes.org.uk or telephone 0113 222 4413. Please have your application number and CBL references to hand. Alternatively, you can call into your local One Stop Centre or Community Hub for assistance. Date of Registration (DOR) : Homes advertised as date of registration (DOR) will be let to the bidder with the earliest date of registration and a local c onnection to the Ward area. Successful bidders will need to provide proof of local connection within 3 days of it being requested. Maps of Ward areas can be found at www.leeds.gov.uk/wardmaps Sep 22 2021 to Sep 27 2021 Ref Landlord Address Area Beds Type Sheltered Adapted Rent Description DOR KING EDWARD AVENUE, HORSFORTH, Single person or couple 60+ 11474 Leeds City Council LEEDS, LS18 4BD Horsforth 1 Bungalow No No 74.68 No INGLEWOOD DRIVE, SEACROFT, Single person or couple 11484 Leeds City Council LEEDS, LS14 6HG Killingbeck and Seacroft 1 Flat No No 65.59 No SWINNOW ROAD, SWINNOW, LEEDS, Single/couple sharing 11502 Leeds City Council LS13 4PJ Pudsey 1 Flat No No 64.86 Yes OAK TREE CRESCENT, GIPTON, Single/couple 11509 Leeds City Council LEEDS, LS9 6SE Gipton and Harehills 1 Flat No No 62.87 No LANDSEER DRIVE, BRAMLEY, LEEDS, Single/couple 35+ 11511 Leeds City Council LS13 2QU Bramley and Stanningley 1 Flat No No 66.26 No MONKSWOOD BANK, -

Summary of the Site Allocations Plan Revised Submission Draft Amendments Within Each Housing Market Characteristic Area (HMCA)

Summary of the Site Allocations Plan Revised Submission Draft Amendments within each Housing Market Characteristic Area (HMCA). AIREBOROUGH HMCA Amendment Site Ref Ward Address Homes Phase Proposed Amendments number as listed in the schedule of amendments RETAINED HOUSING ALLOCATIONS 24 HG2-1 Guiseley & Rawdon New Birks Farm, Ings Lane, Guiseley 160 2 Retain housing allocation. Change to Phase 1. 24 HG2-2 Guiseley & Rawdon Wills Gill, Guiseley 133 2 Retain housing allocation. Change to Phase 1. 24 HG2-4 Guiseley & Rawdon Hollins Hill and Hawkstone Avenue, 80 2 Retain housing allocation. Change to Guiseley Phase 1. 24 HG2-9 Otley & Yeadon Land at Victoria Avenue, Leeds 102 2 Retain housing allocation. Change to Phase 1. TOTAL 475 PREVIOUS HOUSING ALLOCATIONS NOW PROPOSED AS BROAD LOCATIONS 26 HG2-3 Guiseley & Rawdon / Shaw Lane (land at), Guiseley and 234 2 Delete housing allocation and identify Otley & Yeadon Banksfield Mt as Broad Location (BL1-7) 26 HG2-5 Guiseley & Rawdon Land at Coach Road, Guiseley 83 2 Delete housing allocation and identify as Broad Location (BL1-8) 26 HG2-10 Guiseley & Rawdon Gill Lane, Yeadon 155 2 Delete housing allocation and identify as Broad Location (BL1-9) 26 HG2-12 Horsforth Woodlands Drive, Rawdon 25 2 Delete housing allocation and identify as Broad Location (BL1-12) TOTAL 497 PREVIOUS SAFEGUARDED LAND NOW PROPOSED AS BROAD LOCATIONS 26 HG3-1 Guiseley and Rawdon Ings Lane, Guiseley Delete safeguarded land designation 114 - and identify as Broad Location (BL1-6) 26 HG3-2 Horsforth Land to west of Knott -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REVIEW OF WEST YORKSHIRE THE METROPOLITAN BOROUGH OF KIRKLEES Boundary with:- BRADFORD LEEDS HIGH PEAK (DERBYSHIRE) BRADFORD LEEDS WAKEFIELD ROCHDALE KIRKI ES BARNSLEY HIGH PEAK REPORT NO. 659 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO 659 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Mr K F J Ennals CB MEMBERS Mr G R Prentice Mrs H R V Sarkany Mr C W Smith Professor K Young THE RT HON MICHAEL HOWARD MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT REVIEW OF WEST YORKSHIRE THE METROPOLITAN BOROUGH OF KIRKLEES AND ITS BOUNDARIES WITH THE CITIES OF BRADFORD AND LEEDS, AND WITH THE BOROUGH OF HIGH PEAK, IN DERBYSHIRE THE COMMISSION'S FINAL REPORT INTRODUCTION 1 . This report contains our final proposals for the boundaries of the Metropolitan Borough of Kirklees with the Cities of Bradford and Leeds and the Borough of High Peak in Derbyshire. We are not suggesting any radical changes but are making a number of minor proposals to make the boundary more clearly identifiable and to remove anomalies. Our recommendations in respect of the boundaries of Kirklees with Wakefield, Barnsley, Oldham and Calderdale were contained in our earlier reports, no's 600, 601, 611, and 630 respectively. ANNOUNCEMENT OF THE START OF THE REVIEW 2, On 1 September 1987 we wrote to Kirklees Metropolitan Borough Council announcing our intention to undertake a review of Kirklees as part of the mandatory review of West Yorkshire and its Metropolitan Districts under section 48(1) of the Local Government Act 1972. 3. Copies of the letter were sent to the adjoining Metropolitan Boroughs; to county and district councils bordering the metropolitan area; to parish councils in Kirklees and the adjoining districts; to the local authority associations; to Members of Parliament with constituency interests; to the headquarters of the main political parties; to the local press, television and radio stations; and to a number of other interested persons and organisations.