Presidential Elections and Supreme Court Appointments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Defence of the Court's Integrity

In Defence of the Court’s Integrity 17 In Defence of the Court’s Integrity: The Role of Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes in the Defeat of the Court-Packing Plan of 1937 Ryan Coates Honours, Durham University ‘No greater mistake can be made than to think that our institutions are fixed or may not be changed for the worse. We are a young nation and nothing can be taken for granted. If our institutions are maintained in their integrity, and if change shall mean improvement, it will be because the intelligent and the worthy constantly generate the motive power which, distributed over a thousand lines of communication, develops that appreciation of the standards of decency and justice which we have delighted to call the common sense of the American people.’ Hughes in 1909 ‘Our institutions were not designed to bring about uniformity of opinion; if they had been, we might well abandon hope.’ Hughes in 1925 ‘While what I am about to say would ordinarily be held in confidence, I feel that I am justified in revealing it in defence of the Court’s integrity.’ Hughes in the 1940s In early 1927, ten years before his intervention against the court-packing plan, Charles Evans Hughes, former Governor of New York, former Republican presidential candidate, former Secretary of State, and most significantly, former Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, delivered a series 18 history in the making vol. 3 no. 2 of lectures at his alma mater, Columbia University, on the subject of the Supreme Court.1 These lectures were published the following year as The Supreme Court: Its Foundation, Methods and Achievements (New York: Columbia University Press, 1928). -

The Warren Court and the Pursuit of Justice, 50 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 50 | Issue 1 Article 4 Winter 1-1-1993 The aW rren Court And The Pursuit Of Justice Morton J. Horwitz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Morton J. Horwitz, The Warren Court And The Pursuit Of Justice, 50 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 5 (1993), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol50/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE WARREN COURT AND THE PURSUIT OF JUSTICE MORTON J. HoRwiTz* From 1953, when Earl Warren became Chief Justice, to 1969, when Earl Warren stepped down as Chief Justice, a constitutional revolution occurred. Constitutional revolutions are rare in American history. Indeed, the only constitutional revolution prior to the Warren Court was the New Deal Revolution of 1937, which fundamentally altered the relationship between the federal government and the states and between the government and the economy. Prior to 1937, there had been great continuity in American constitutional history. The first sharp break occurred in 1937 with the New Deal Court. The second sharp break took place between 1953 and 1969 with the Warren Court. Whether we will experience a comparable turn after 1969 remains to be seen. -

Student's Name

California State & Local Government In Crisis, 6th ed., by Walt Huber CHAPTER 6 QUIZ - © January 2006, Educational Textbook Company 1. Which of the following is NOT an official of California's plural executive? (p. 78) a. Attorney General b. Speaker of the Assembly c. Superintendent of Public Instruction d. Governor 2. Which of the following are requirements for a person seeking the office of governor? (p. 78) a. Qualified to vote b. California resident for 5 years c. Citizen of the United States d. All of the above 3. Which of the following is NOT a gubernatorial power? (p. 79) a. Real estate commissioner b. Legislative leader c. Commander-in-chief of state militia d. Cerimonial and political leader 4. What is the most important legislative weapon the governor has? (p. 81) a. Line item veto b. Full veto c. Pocket veto d. Final veto 5. What is required to override a governor's veto? (p. 81) a. Simple majority (51%). b. Simple majority in house, two-thirds vote in senate. c. Two-thirds vote in both houses. d. None of the above. 6. Who is considered the most important executive officer in California after the governor? (p. 83) a. Lieutenant Governor b. Attorney General c. Secretary of State d. State Controller 1 7. Who determines the policies of the Department of Education? (p. 84) a. Governor b. Superintendent of Public Instruction c. State Board of Education d. State Legislature 8. What is the five-member body that is responsible for the equal assessment of all property in California? (p. -

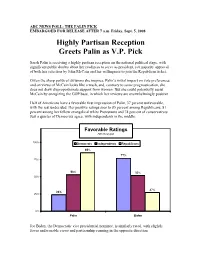

Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin As V.P. Pick

ABC NEWS POLL: THE PALIN PICK EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 7 a.m. Friday, Sept. 5, 2008 Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin as V.P. Pick Sarah Palin is receiving a highly partisan reception on the national political stage, with significant public doubts about her readiness to serve as president, yet majority approval of both her selection by John McCain and her willingness to join the Republican ticket. Given the sharp political divisions she inspires, Palin’s initial impact on vote preferences and on views of McCain looks like a wash, and, contrary to some prognostication, she does not draw disproportionate support from women. But she could potentially assist McCain by energizing the GOP base, in which her reviews are overwhelmingly positive. Half of Americans have a favorable first impression of Palin, 37 percent unfavorable, with the rest undecided. Her positive ratings soar to 85 percent among Republicans, 81 percent among her fellow evangelical white Protestants and 74 percent of conservatives. Just a quarter of Democrats agree, with independents in the middle. Favorable Ratings ABC News poll 100% Democrats Independents Republicans 85% 77% 75% 53% 52% 50% 27% 24% 25% 0% Palin Biden Joe Biden, the Democratic vice presidential nominee, is similarly rated, with slightly fewer unfavorable views and partisanship running in the opposite direction. Palin: Biden: Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable All 50% 37 54% 30 Democrats 24 63 77 9 Independents 53 34 52 31 Republicans 85 7 27 60 Men 54 37 55 35 Women 47 36 54 27 IMPACT – The public by a narrow 6-point margin, 25 percent to 19 percent, says Palin’s selection makes them more likely to support McCain, less than the 12-point positive impact of Biden on the Democratic ticket (22 percent more likely to support Barack Obama, 10 percent less so). -

Picking the Vice President

Picking the Vice President Elaine C. Kamarck Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. Contents Introduction 4 1 The Balancing Model 6 The Vice Presidency as an “Arranged Marriage” 2 Breaking the Mold 14 From Arranged Marriages to Love Matches 3 The Partnership Model in Action 20 Al Gore Dick Cheney Joe Biden 4 Conclusion 33 Copyright 36 Introduction Throughout history, the vice president has been a pretty forlorn character, not unlike the fictional vice president Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays in the HBO seriesVEEP . In the first episode, Vice President Selina Meyer keeps asking her secretary whether the president has called. He hasn’t. She then walks into a U.S. senator’s office and asks of her old colleague, “What have I been missing here?” Without looking up from her computer, the senator responds, “Power.” Until recently, vice presidents were not very interesting nor was the relationship between presidents and their vice presidents very consequential—and for good reason. Historically, vice presidents have been understudies, have often been disliked or even despised by the president they served, and have been used by political parties, derided by journalists, and ridiculed by the public. The job of vice president has been so peripheral that VPs themselves have even made fun of the office. That’s because from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the last decade of the twentieth century, most vice presidents were chosen to “balance” the ticket. The balance in question could be geographic—a northern presidential candidate like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts picked a southerner like Lyndon B. -

Suffolk University Virginia General Election Voters SUPRC Field

Suffolk University Virginia General Election Voters AREA N= 600 100% DC Area ........................................ 1 ( 1/ 98) 164 27% West ........................................... 2 51 9% Piedmont Valley ................................ 3 134 22% Richmond South ................................. 4 104 17% East ........................................... 5 147 25% START Hello, my name is __________ and I am conducting a survey for Suffolk University and I would like to get your opinions on some political questions. We are calling Virginia households statewide. Would you be willing to spend three minutes answering some brief questions? <ROTATE> or someone in that household). N= 600 100% Continue ....................................... 1 ( 1/105) 600 100% GEND RECORD GENDER N= 600 100% Male ........................................... 1 ( 1/106) 275 46% Female ......................................... 2 325 54% S2 S2. Thank You. How likely are you to vote in the Presidential Election on November 4th? N= 600 100% Very likely .................................... 1 ( 1/107) 583 97% Somewhat likely ................................ 2 17 3% Not very/Not at all likely ..................... 3 0 0% Other/Undecided/Refused ........................ 4 0 0% Q1 Q1. Which political party do you feel closest to - Democrat, Republican, or Independent? N= 600 100% Democrat ....................................... 1 ( 1/110) 269 45% Republican ..................................... 2 188 31% Independent/Unaffiliated/Other ................. 3 141 24% Not registered -

The Impartiality Paradox

The Impartiality Paradox Melissa E. Loewenstemt The constitutional principles that bind our free society instruct that the American people must "hold the judgeship in the highest esteem, that they re- gard it as the symbol of impartial, fair, and equal justice under law."'1 Accord- ingly, in contrast with the political branches, the Supreme Court's decisions "are legitimate only when [the Court] seeks to dissociate itself from individual 2 or group interests, and to judge by disinterested and more objective standards." As Justice Frankfurter said, "justice must satisfy the appearance of justice. 3 Almost instinctively, once a President appoints a judge to sit on the Su- preme Court,4 the public earmarks the Justice as an incarnation of impartiality, neutrality, and trustworthiness. Not surprisingly then, Presidents have looked to the Court for appointments to high profile and important committees of national concern. 5 It is among members of the judiciary that a President can find individuals certain to obtain the immediate respect of the American people, and often the world community. It is a judge's neutrality, fair-mindedness, and integrity that once again label him a person of impartiality and fairness, a per- son who seeks justice, and a President's first choice to serve the nation. The characteristics that led to a judge's initial appointment under our adversary sys- tem, and which lend themselves to appearances of propriety and justice in our courts, often carry over into extrajudicial activities as well. As Ralph K. Winter, Jr., then a professor at the Yale Law School, stated: [t]he appointment of a Justice of the Supreme Court to head a governmental com- mission or inquiry usually occurs because of the existence of a highly controversial issue which calls for some kind of official or authoritative resolution ....And the use of Supreme Court Justices, experience shows, is generally prompted by a presi- t Yale Law School, J.D. -

Earl Warren: a Political Biography, by Leo Katcher; Warren: the Man, the Court, the Era, by John Weaver

Indiana Law Journal Volume 43 Issue 3 Article 14 Spring 1968 Earl Warren: A Political Biography, by Leo Katcher; Warren: The Man, The Court, The Era, by John Weaver William F. Swindler College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Judges Commons, and the Legal Biography Commons Recommended Citation Swindler, William F. (1968) "Earl Warren: A Political Biography, by Leo Katcher; Warren: The Man, The Court, The Era, by John Weaver," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 43 : Iss. 3 , Article 14. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol43/iss3/14 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS EARL WARREN: A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY. By Leo Katcher. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967. Pp. i, 502. $8.50. WARREN: THEi MAN, THE COURT, THE ERA. By John D. Weaver. Boston: Little. Brown & Co., 1967. Pp. 406. $7.95. Anyone interested in collecting a bookshelf of serious reading on the various Chief Justices of the United States is struck at the outset by the relative paucity of materials available. Among the studies of the Chief Justices of the twentieth century there is King's Melville Weston, Fuller,' which, while not definitive, is reliable and adequate enough to have merited reprinting in the excellent paperback series being edited by Professor Philip Kurland of the University of Chicago. -

Abington School District V. Schempp 1 Ableman V. Booth 1 Abortion 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 Bill of Rights 66 Birth Control and Contraception 71 Abington School District v. Schempp 1 Hugo L. Black 73 Ableman v. Booth 1 Harry A. Blackmun 75 Abortion 2 John Blair, Jr. 77 Adamson v. California 8 Samuel Blatchford 78 Adarand Constructors v. Peña 8 Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell 79 Adkins v. Children’s Hospital 10 Bob Jones University v. United States 80 Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl 13 Boerne v. Flores 81 Advisory Opinions 15 Bolling v. Sharpe 81 Affirmative Action 15 Bond v. United States 82 Afroyim v. Rusk 21 Boumediene v. Bush 83 Age Discrimination 22 Bowers v. Hardwick 84 Samuel A. Alito, Jr. 24 Boyd v. United States 86 Allgeyer v. Louisiana 26 Boy Scouts of America v. Dale 86 Americans with Disabilities Act 27 Joseph P. Bradley 87 Antitrust Law 29 Bradwell v. Illinois 89 Appellate Jurisdiction 33 Louis D. Brandeis 90 Argersinger v. Hamlin 36 Brandenburg v. Ohio 92 Arizona v. United States 36 William J. Brennan, Jr. 92 Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing David J. Brewer 96 Development Corporation 37 Stephen G. Breyer 97 Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition 38 Briefs 99 Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority 38 Bronson v. Kinzie 101 Assembly and Association, Freedom of 39 Henry B. Brown 101 Arizona v. Gant 42 Brown v. Board of Education 102 Atkins v. Virginia 43 Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association 104 Automobile Searches 45 Brown v. Maryland 106 Brown v. Mississippi 106 Bad Tendency Test 46 Brushaber v. Union Pacific Railroad Company 107 Bail 47 Buchanan v. -

Supreme Court of the United States Washington, D.C

Supreme Court of the United States Washington, D.C. Pointe-au-Pic, Canada, July 25, 1928. My dear George: I have your letter of July 3d, and am delighted to read it and to follow you and Mrs. Sutherland in your delightful journey through Italy. My wife’s sister, Miss Maria Herron, has done a great deal of traveling in Italy and elsewhere, and she says that you have marked out for yourselves one of the most delightful trips in the World. I have been through part of it myself, and therefore know enough to congratulate you. I sincerely hope that you find Cadenabbia just as good now as it was when you wrote the letter, and that you find that your rest is accomplishing the result that your doctor had in mind. Of course we are most anxious about the election of Hoover, and I am bound to say that I think the Republicans feel that the chances are strongly in favor of Hoover’s election, but I don’t know how wisely they judge. There are so many cross currents in the election that it is hard to calculate what their effect will be, but as the campaign opens, it is fairly clear that the farm question is entirely out of the picture. Even old Norris says that they can not have another party, and the consequence is that if Smith is going to win, he has got to do it with New York, New Jersey, Connecticut and Massachusetts, and by a retention of all the southern States. -

Supreme Court Justices

The Supreme Court Justices Supreme Court Justices *asterick denotes chief justice John Jay* (1789-95) Robert C. Grier (1846-70) John Rutledge* (1790-91; 1795) Benjamin R. Curtis (1851-57) William Cushing (1790-1810) John A. Campbell (1853-61) James Wilson (1789-98) Nathan Clifford (1858-81) John Blair, Jr. (1790-96) Noah Haynes Swayne (1862-81) James Iredell (1790-99) Samuel F. Miller (1862-90) Thomas Johnson (1792-93) David Davis (1862-77) William Paterson (1793-1806) Stephen J. Field (1863-97) Samuel Chase (1796-1811) Salmon P. Chase* (1864-73) Olliver Ellsworth* (1796-1800) William Strong (1870-80) ___________________ ___________________ Bushrod Washington (1799-1829) Joseph P. Bradley (1870-92) Alfred Moore (1800-1804) Ward Hunt (1873-82) John Marshall* (1801-35) Morrison R. Waite* (1874-88) William Johnson (1804-34) John M. Harlan (1877-1911) Henry B. Livingston (1807-23) William B. Woods (1881-87) Thomas Todd (1807-26) Stanley Matthews (1881-89) Gabriel Duvall (1811-35) Horace Gray (1882-1902) Joseph Story (1812-45) Samuel Blatchford (1882-93) Smith Thompson (1823-43) Lucius Q.C. Lamar (1883-93) Robert Trimble (1826-28) Melville W. Fuller* (1888-1910) ___________________ ___________________ John McLean (1830-61) David J. Brewer (1890-1910) Henry Baldwin (1830-44) Henry B. Brown (1891-1906) James Moore Wayne (1835-67) George Shiras, Jr. (1892-1903) Roger B. Taney* (1836-64) Howell E. Jackson (1893-95) Philip P. Barbour (1836-41) Edward D. White* (1894-1921) John Catron (1837-65) Rufus W. Peckham (1896-1909) John McKinley (1838-52) Joseph McKenna (1898-1925) Peter Vivian Daniel (1842-60) Oliver W. -

John S. Mccain III • Born in Panama on August 29, 1936 • Nicknamed

John S. McCain III • Born in Panama on August 29, 1936 • Nicknamed ”The Maverick” for not being afraid to disagree with his political party (Republican) • Naval aviator during the Vietnam War • Prisoner of war in Vietnam from 1967-1973 • Arizona senator since 1986 • Republican nominee for president of the United States in 2008 McCain in the Navy McCain’s father and grandfather were both admirals in the Navy. He followed in their footsteps and graduated from the Naval Academy in 1958. He is pictured here with his parents and his younger brother, Joe. His son, Jimmy, also became an officer in the Navy McCain in training (1965) As the U.S. began to increase the number of troops in Vietnam in 1965, McCain was training to become a fighter pilot. On October 26, 1967, his A-4 Skyhawk was shot down by a missile as he was flying over Hanoi. He was badly injured when he was pulled from Truc Bach Lake by North Vietnamese. Shot Down McCain’s bomber was hit by a surface-to-air missile on Oct. 26, 1967, destroying the aircraft’s right wing. According to McCain, the plane entered an “inverted, almost straight-down spin,” and he ejected. But the sheer force of the ejection broke his right leg and both arms, knocking him unconscious, the report said. McCain came to as he landed in a lake, but burdened by heavy equipment, he sank straight to the bottom. Able to kick to the surface momentarily for air, he somehow managed to activate his life preserver with his teeth.