Overlap in the Wing Shape of Migratory, Nomadic and Sedentary Grass Parrots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Hollow Using Species List & Nest Box Designs for the High Country Bushfire Zones

1 Hollow Using Species List & Nest Box Designs For the High Country Bushfire Zones Compiled by Alice McGlashan Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/nestboxtales/ Website: www.nestboxtales.com Sharing stories and knowledge about nest boxes for Australian native animals to encourage everyone to improve habitat for wildlife. 2 Background Studies across Australia have found that fire tends to reduce the number of hollows in an ecosystem for the short to medium term (0-50+ years). The hotter and more damaging the fire, the greater the loss of tree hollows. Consider an old, large, wizened, partially dead tree with many small to large sized hollows, being somewhat of an apartment block for hollow using wildlife. Trees such as these do not tend to survive very destructive bushfires, such as those that have occurred during this bushfire season (summer 2019-20) These same studies have found that hollow using species don’t initially return to badly burnt areas, and when they do, the numbers are extremely low compared to before the fire. By comparison, non-hollow using species generally bounce back relatively quickly and in a few years are similar in numbers to those pre-fire. This provides an indication that it is likely to be the lack of hollows, rather than food sources and habitat other than tree hollows, that are the limiting factor for the return of hollow using species to recently burnt areas. Aside: the studies to date have been on smaller patch burns or areas that are dwarfed in size by the vast expanses of forests burnt, particularly in the Eastern states of Australia during the bushfire season of 2019-20. -

Habitat Types

Habitat Types The following section features ten predominant habitat types on the West Coast of the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. It provides a description of each habitat type and the native plant and fauna species that commonly occur there. The fauna species lists in this section are not limited to the species included in this publication and include other coastal fauna species. Fauna species included in this publication are printed in bold. Information is also provided on specific threats and reference sites for each habitat type. The habitat types presented are generally either characteristic of high-energy exposed coastline or low-energy sheltered coastline. Open sandy beaches, non-vegetated dunefields, coastal cliffs and cliff tops are all typically found along high energy, exposed coastline, while mangroves, sand flats and saltmarsh/samphire are characteristic of low energy, sheltered coastline. Habitat Types Coastal Dune Shrublands NATURAL DISTRIBUTION shrublands of larger vegetation occur on more stable dunes and Found throughout the coastal environment, from low beachfront cliff-top dunes with deep stable sand. Most large dune shrublands locations to elevated clifftops, wherever sand can accumulate. will be composed of a mosaic of transitional vegetation patches ranging from bare sand to dense shrub cover. DESCRIPTION This habitat type is associated with sandy coastal dunes occurring The understory generally consists of moderate to high diversity of along exposed and sometimes more sheltered coastline. Dunes are low shrubs, sedges and groundcovers. Understory diversity is often created by the deposition of dry sand particles from the beach by driven by the position and aspect of the dune slope. -

Birdquest Australia (Western and Christmas

Chestnut-backed Button-quail in the north was a bonus, showing brilliantly for a long time – unheard of for this family (Andy Jensen) WESTERN AUSTRALIA 5/10 – 27 SEPTEMBER 2017 LEADER: ANDY JENSEN ASSISTANT: STUART PICKERING ! ! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Western Australia (including Christmas Island) 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com Western Shrike-tit was one of the many highlights in the southwest (Andy Jensen) Western Australia, if it were a country, would be the 10th largest in the world! The BirdQuest Western Australia (including Christmas Island) 2017 tour offered an unrivalled opportunity to cover a large portion of this area, as well as the offshore territory of Christmas Island (located closer to Indonesia than mainland Australia). Western Australia is a highly diverse region with a range of habitats. It has been shaped by the isolation caused by the surrounding deserts. This isolation has resulted in a richly diverse fauna, with a high degree of endemism. A must visit for any birder. This tour covered a wide range of the habitats Western Australia has to offer as is possible in three weeks, including the temperate Karri and Wandoo woodlands and mallee of the southwest, the coastal heathlands of the southcoast, dry scrub and extensive uncleared woodlands of the goldfields, coastal plains and mangroves around Broome, and the red-earth savannah habitats and tropical woodland of the Kimberley. The climate varied dramatically Conditions ranged from minus 1c in the Sterling Ranges where we were scraping ice off the windscreen, to nearly 40c in the Kimberley, where it was dust needing to be removed from the windscreen! We were fortunate with the weather – aside from a few minutes of drizzle as we staked out one of the skulkers in the Sterling Ranges, it remained dry the whole time. -

Elegant Parrot

Elegant Parrot FAMILY: Psittacidae GENUS: Neophema SPECIES: elegans OTHER NAMES: Elegant Grass-parakeet, Grass-parakeet. Description: Small parrot displaying little sexual dimorphism. Male's crown, nape and uppers golden- olive. Blue band on forehead (extending beyond the eye) with pale blue line above it. Yellow between eye and beak. Wings olive with dark blue on margin. Turquoise shoulder patch (narrow). Flight feathers deep blue, central tail feathers dull blue, outers blue edged with yellow. Underparts including underside of tail yellow. Adult females resemble males but is duller in colour on upper parts and lacks golden tinge. Flight feathers brown. Immatures are duller versions of the adults and lack the band on forehead. Young cocks are usually more yellow on underparts than hens, and young hens usually have a pale stripe under the wings which disappears after the first moult. The Elegant Parrot is most often encountered in flocks of 20-100 or more, except in the breeding season when tend to be found either in pairs or small parties. It, like other Neophemas, is quiet, unobtrusive and forages almost entirely on the ground. Its flight is high, swift and direct. Partly nomadic, the Elegant Parrot may be encountered in the company of the Blue-winged Parrot. Length: 225mm. Subspecies: None. Distribution: From south-western NSW to the Mt Lofty Ranges and Kangaroo Island in SA and in WA from Esperance to Perth. Habitat: Heathland and open country, open woodland, cropland and semiarid scrub. Diet: Seeds of grasses and herbacious plants. Breeding: August-January. The usual nesting site is a small tree cavity near the ground. -

Aesthetics, Economics and Conservation of the Endangered Orange-Bellied Parrot

Agenda, Volume 7, Number 2, 2000, pages 153-166 Aesthetics, Economics and Conservation of the Endangered Orange-Bellied Parrot Harry Clarke r T l h e Orange-bellied Parrot (N. chrysogaster), or OBP, is an exceedingly rare Australian parrot and, indeed, one of the world’s rarest birds. The genus X Neophema to which it belongs comprise small, graceful grass parrots in the family Psittacidae that include both parrots and lorikeets. They are ground dwelling and southern-based Australian parrots. Apart from the OBP, members include the Turquoise Parrot (N. pulchella), the Scarlet-chested Parrot (N. splendida), the Blue-winged Parrot (N. chrysostoma), the Elegant Parrot (N. elegans) and the Rock Parrot (N. petrophila). Members of this genus are described by Trounson (1996:54) as ‘among the most beautiful of birds’. All are endemic to Australia and none, except the Blue-winged Parrot, are common with the OBP being by far the most rare. Bourke’s Parrot (N. bourkii) formerly classified with this genus, is now placed in a different genus (Christidis and Boles, 1994). The OBP breeds in summer on the south-west coast of Tasmania in hollow bearing eucalypts which grow adjacent to the buttongrass plains where it feeds. On completion of its breeding season, the population migrates north across Bass Strait via King Island during March-April. Most OBPs then reside in the south east region of Australia between Gippsland, eastern Victoria and The Coorong in south-eastern South Australia. Particular concentrations of OBPs are found in the saltmarshes of Port Phillip Bay (Forshaw (1989:284) claims up to 70 per cent live in this habitat) where they feed on salt-resistant plants restricted to this habitat (Loyn et al, 1986). -

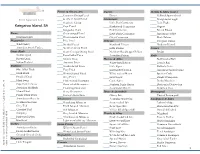

Bird Species Checklist

Petrels & Shearwaters Darters Hawks & Allies (cont.) Common Diving-Petrel Darter Collared Sparrowhawk Bird Species List Southern Giant Petrel Cormorants Wedge-tailed Eagle Southern Fulmar Little Pied Cormorant Little Eagle Kangaroo Island, SA Cape Petrel Black-faced Cormorant Osprey Kerguelen Petrel Pied Cormorant Brown Falcon Emus Great-winged Petrel Little Black Cormorant Australian Hobby Mainland Emu White-headed Petrel Great Cormorant Black Falcon Megapodes Blue Petrel Pelicans Peregrine Falcon Wild Turkey Mottled Petrel Fiordland Pelican Nankeen Kestrel Australian Brush Turkey Northern Giant Petrel Little Pelican Cranes Game Birds South Georgia Diving Petrel Northern Rockhopper Pelican Brolga Stubble Quail Broad-billed Prion Australian Pelican Rails Brown Quail Salvin's Prion Herons & Allies Buff-banded Rail Indian Peafowl Antarctic Prion White-faced Heron Lewin's Rail Wildfowl Slender-billed Prion Little Egret Baillon's Crake Blue-billed Duck Fairy Prion Eastern Reef Heron Australian Spotted Crake Musk Duck White-chinned Petrel White-necked Heron Spotless Crake Freckled Duck Grey Petrel Great Egret Purple Swamp-hen Black Swan Flesh-footed Shearwater Cattle Egret Dusky Moorhen Cape Barren Goose Short-tailed Shearwater Nankeen Night Heron Black-tailed Native-hen Australian Shelduck Fluttering Shearwater Australasian Bittern Common Coot Maned Duck Sooty Shearwater Ibises & Spoonbills Buttonquail Pacific Black Duck Hutton's Shearwater Glossy Ibis Painted Buttonquail Australasian Shoveler Albatrosses Australian White Ibis Sandpipers -

Orange Bellied Parro

Orange-bellied Parrot Husbandry Guidelines Edited by Jocelyn Hockley, DPIPWE, Tasmania. For enquiries please contact: Jocelyn Hockley GPO Box 44 Hobart. Tas. 7001. [email protected] Cover Photo Credit: Jocelyn Hockley, DPIPWE. Tasmania. 1.0 Introduction 1.1 General Features The Orange-bellied Parrot is one of six small grass parrots forming the genus Neophema. A bright grass- green bird with, royal blue leading edges to the wings light green to bright yellow underside, with a distinctive orange patch on the belly. It is a migratory bird, which breeds only in coastal southwest Tasmania and spends winter in coastal Victoria and South Australia. The Orange-bellied Parrot Neophema chrysogaster was one of the first Australian birds to be described by Latham in 1790 and is now one of Australia’s rarest bird species, currently classified as Critically Endangered it is strictly protected by CITES and a variety of Australian Commonwealth and State legislations. The wild population of Orange-bellied Parrots is believed to number under 50 individuals. 1.2 History in Captivity Although many parrot species have a long and well-documented history in captivity, due to their conservation status the Orange-bellied parrot is not currently found among aviculturists (Sindel & Gill 1992). A pair of Orange-bellied Parrots was exhibited at London Zoo in the early 1900s. In the late 1960s and early 1970s many Orange-bellied Parrots were illegally trapped and exported to Europe. In Australia the first authenticated documentation of breeding Orange-bellied Parrots in captivity was in South Australia in 1973 (Shephard 1994). -

Turquoise Parrot

TAXON SUMMARY Turquoise Parrot 1 Family Psittacidae 2 Scientific name Neophema pulchella Shaw, 1794 3 Common name Turquoise Parrot 4 Conservation status Near Threatened: a 5 Reasons for listing inappropriate burning that may favour a shrubby over Although currently expanding, the area of occupancy the grassy understorey the parrots require (Quin, 1990, of this species is still probably less than half of the size Quin and Baker-Gabb, 1993). that it was a century ago (Near Threatened: a). Estimate Reliability Extent of occurrence 630,000 km2 medium trend stable medium Area of occupancy 20,000 km2 low trend increasing medium No. of breeding birds 20,000 low trend increasing medium No. of sub-populations 1 medium Generation time 3 years medium 6 Infraspecific taxa None described. 11 Recommended actions 7 Past range and abundance 11.1 Conserve native pasture and promote its use. Throughout south-east Australia from Suttor R., 11.2 Maintain a buffer around known nesting areas inland from Mackay, Qld, through eastern New South in forests managed for timber production. Wales, including suburban Sydney, to Melbourne, Vic. Declined rapidly in 1890s, with no reports of 11.3 Maintain or establish feral predator control in substantial numbers until 1920s (Jarman, 1973, nesting areas. Higgins, 1999). 11.4 Maintain a fire regime that establishes a mosaic 8 Present range and abundance of fire ages. In Queensland, now no further north than 12 Bibliography Maryborough and Fraser I., distribution in New South Higgins, P. J. (ed.) 1999. Handbook of Australian, Wales patchy and, in Victoria, largely confined to New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. -

Birds of Flinders Chase National Park

Flinders Chase National Park List of birds The following list includes all bird species known from Flinders Chase National Park. 126 are listed (including two native to Australia but introduced to Kangaroo Island, and four introduced to Australia). The species range from the extremely common, to those known from only a few sightings. It is worth remembering that some birds are migratory and can be seen only at certain times of the year (for example many of the coastal seabirds are seen only in the winter months). An invaluable source of information for any keen birdwatcher is Birds of Kangaroo Island – A Photographic Field Guide by Chris Baxter (2015, ATF Press). Nomenclature and sequence in this bird list has been taken from An annotated list of the birds of Kangaroo Island by Chris Baxter (1995, National Parks and Wildlife Service), which follows Christidis and Boles (1995) The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories. The details on bird status and habitat preference for Kangaroo Island have been taken from Baxter (2005) (see key on last page for explanations). COMMON NAME SPECIES NAME STATUS AND HABITAT ON KANGAROO ISLAND MEGAPODIIDAE – Mound builders # Australian Brush-turkey Alectura lathami A, M, B, 4, 6 ANATIDAE – Swans, ducks & geese Musk Duck Biziura lobata A, M, B, 2, 3 Black Swan Cygnus atratus A, H, B, 2, 3, (7) # Cape Barren Goose Cereopsis novaehollandiae A, M, B, (2), 3, 7 Australian Shelduck (Mountain Duck) Tadorna tadornoides A, H, B, 2, 3, 7 Australian Wood Duck Chenonetta jubata A, M, B, 3, 7 Pacific -

Managing Bird Damage

Managing Bird Damage Managing Bird Managing Bird Damage Bird damage is a significant problem in Australia with total to Fruit and Other Horticultural Crops damage to horticultural production estimated at nearly $300 million annually. Over 60 bird species are known to damage horticultural crops. These species possess marked differences in feeding strategies and movement patterns which influence the nature, timing and severity of the damage they cause. Reducing bird damage is difficult because of the to Fruit and Other Horticultural Crops Fruit and Other Horticultural to unpredictability of damage from year to year and a lack of information about the cost-effectiveness of commonly used management practices. Growers therefore need information on how to better predict patterns of bird movement and abundance, and simple techniques to estimate the extent of damage to guide future management investment. This book promotes the adoption of a more strategic approach to bird management including use of better techniques to reduce damage and increased cooperation between neighbours. Improved collaboration and commit- John Tracey ment from industry and government is also essential along with reconciliation of legislation and responsibilities. Mary Bomford Whilst the focus of this review is pest bird impacts on Quentin Hart horticulture, most of the issues are of relevance to pest bird Glen Saunders management in general. Ron Sinclair DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, FISHERIES AND FORESTRY Managing Bird Damage Managing Bird Managing Bird Damage Bird damage is a significant problem in Australia with total to Fruit and Other Horticultural Crops damage to horticultural production estimated at nearly $300 million annually. Over 60 bird species are known to damage horticultural crops. -

The Status of the Elegant Parrot and the Rock Parrot on Kangaroo Island- C

164 SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST, 28 THE STATUS OF THE ELEGANT PARROT AND THE ROCK PARROT ON KANGAROO ISLAND- C. BAXTER AND S. A. PARKER Accepted April 1980 The status on Kangaroo Island of the Elegant on road, Yacca Flat, 22 January; 12 in pasture Parrot Neophema elegans is not well understood. near D'Estrees Bay, 15 March, and six in same Of its status iri 'South Australia generally, Con area two days later. 1979-80: four, Western don (1969: 63) wrote: "Common and fairly Highway 3 km north of Flinders Chase NP main widespread in southern wetter districts, includ entrance, 2 December; one in melaleuca swamp ing Kangaroo Island', but gave no details. ca 2 km northeast of Karatta School, 7 Decem Abbott (1974) considered the species 'apparent ber; two flying low over heath in firebreak, 16 ly accidental' to the Island, citing Sutton's km north of Flinders Chase main entrance, 1 tentative report of one at Eleanor River on 28 January; one flying up from road ca 3.2 km January 1926 (see below). Further records have north of Cape du Couedic lighthouse, 4 Janu allowed a fresh appraisal of the matter: ary; four on Western Highway ca 5 kill north R. Collier, in Cox (1976): noted near Flin of Flinders Chase entrance, 12 January; one ders Chase, November 1973. flying up from regenerating swampy heath in H. J. Eckert (pers. comm.): 4-5 birds ca 3.2 firebreak on. The Shackle Toad ca 13 km north km south of Willoughby Telephone Exchange, of Flinders Chase homestead, 15 January; one Dudley Peninsula, 13 January 1976; one sub flying up from regenerating firebreak on south adult male collected (SAM B30282).